Ralph J. Gleason Book Explores the Life & Legacy of a Pioneering Music Critic: Author Interview

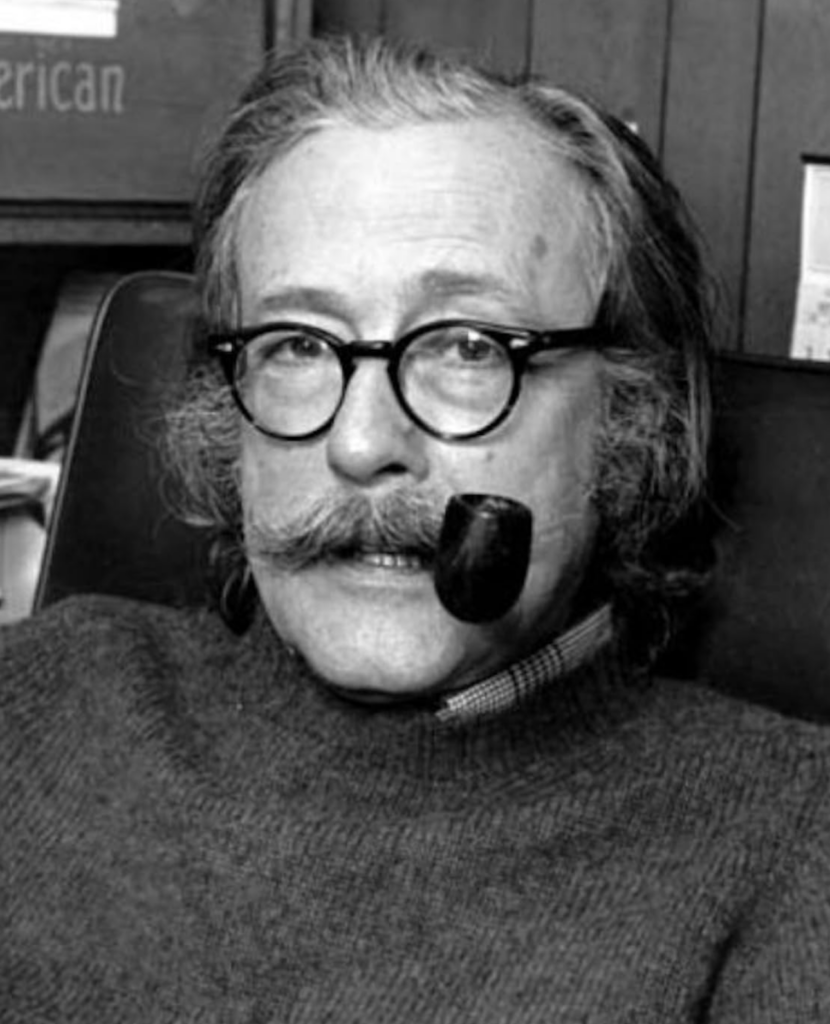

by Jeff Tamarkin By the time Ralph J. Gleason became one of the most important and respected rock critics in the mid-‘60s, he had already been covering jazz for some three decades. That alone set Gleason apart from his peers in both jazz and rock journalism: Born in 1917, he was approaching his 50th birthday when rock music hit its full stride, yet he was accepted as one of the most knowledgeable and astute observers of the scene as it unfolded—by both musicians and fans.

By the time Ralph J. Gleason became one of the most important and respected rock critics in the mid-‘60s, he had already been covering jazz for some three decades. That alone set Gleason apart from his peers in both jazz and rock journalism: Born in 1917, he was approaching his 50th birthday when rock music hit its full stride, yet he was accepted as one of the most knowledgeable and astute observers of the scene as it unfolded—by both musicians and fans.

Gleason’s first reviews were published in 1934 when he attended Columbia University, after which he launched Jazz Information, one of the first jazz periodicals in the U.S. In 1950, he became a staff member at the San Francisco Chronicle, a position that gave him a front-row seat for the city’s active jazz scene. He remained there for many years and, in that capacity, was instrumental in helping to launch the Monterey Jazz Festival and in bringing cutting-edge jazz to television, hosting Jazz Casual, a series that began as a local program, then became syndicated and broadcast across the country, bringing artists such as John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, B.B. King and Dave Brubeck into homes around the Bay Area. Gleason also wrote for Down Beat, the jazz magazine, as well as numerous other publications. He also wrote liner notes for many jazz albums, including titles by Miles Davis, Frank Sinatra and others.

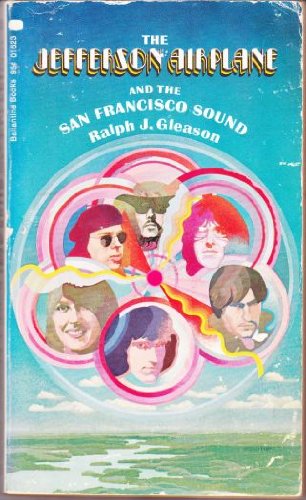

But Ralph Joseph Gleason’s interests weren’t confined to jazz, and when rock music began breaking out in the mid-’60s with the Beatles, Bob Dylan and then the numerous bands sprouting around him in San Francisco—Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, etc.—Gleason became an avid supporter, interviewing the bands, seeing their shows and making a strong case for their creative vitality. His 1969 book The Jefferson Airplane and the San Francisco Sound featured interviews with the band members and was one of the first rock books to treat the music seriously.

Gleason joined with fellow Ramparts contributor Jann Wenner in 1967 to start Rolling Stone magazine, and was listed in its masthead as a founding editor, often contributing his writings to the publication in its formative years—his name remains on that masthead today.

Gleason was—as any good music critic should be—opinionated but fair, and he always kept his ears open, championing new sounds up until his premature death at age 58 in 1975.

In 1990, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame initiated the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award, which irregularly draws attention to important books on the subject of music.

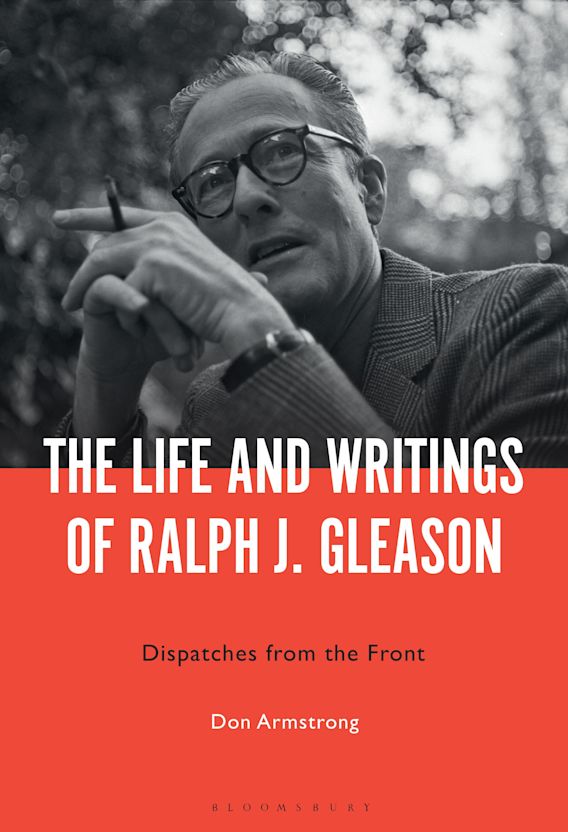

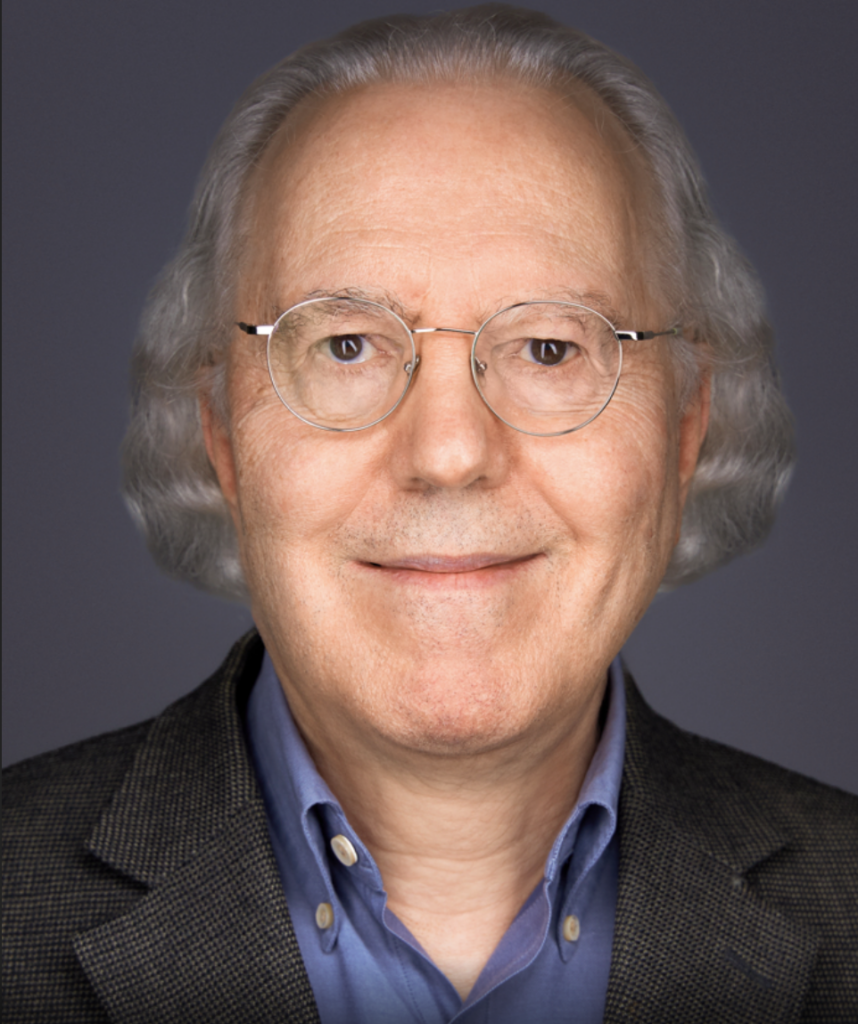

Now, Gleason himself is the subject of a new volume, The Life and Writings of Ralph J. Gleason: Dispatches from the Front (Bloomsbury Academic), written by Don Armstrong, a freelance writer and retired professor, who created the Music Journalism History website and a Facebook group under the same name. Armstrong spoke with Best Classic Bands about the book and the life and legacy of the still-influential Ralph J. Gleason. [The book is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

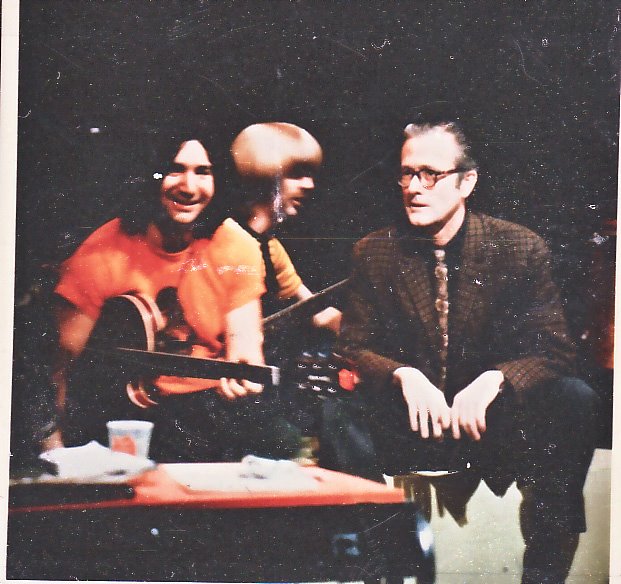

Ralph J. Gleason (r.) with the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh in 1967 (Photo from Gleason’s Facebook page; photographer unknown)

Best Classic Bands : What basic facts should people know about Ralph J. Gleason?

Don Armstrong: Ralph Gleason changed what it meant to be a music journalist. He wrote from the mid-1930s to the mid-1970s, a critical period in the development of popular music. Gleason impacted the careers of prominent musicians, from John Coltrane to Jefferson Airplane. He co-founded Rolling Stone magazine and protested its early turn to celebrity journalism. His type of dissident music journalism is sorely needed today.

Why did you want to write a book about him?

I read Gleason as a teen rock fan in the 1960s, and he influenced my tastes. My interest in writing about Gleason came at a time in my career as an architecture professor when I was ready for a change. Having written about the unrecognized contributions of Black architects and builders, I empathized with Gleason’s drive to do the same for marginalized Black musicians.

The book serves as both a bio and an anthology of his writings. Why did you structure it that way?

The interplay of Gleason’s personal life, career and writings underlay my view of his significance. As I learned from his children and his correspondence, there was a backstory to Gleason’s writings. For example, his sudden awakening to the Beatles and Dylan came following a midlife crisis in which he considered resigning from his job as a column writer. This music gave him a new lease on life, and he became one of the first rock critics.

How would you describe Gleason’s writing?

Gleason’s writing ranged from standard entertainment-column fare to flights of transcendent music writing, some of the best passages in that idiom. His texts often had an improvisational quality that perfectly expressed his impressions of a recent show or recording he had heard. But the thing that most distinguished Gleason from his peers was his multi-genre beat. He was the first critic to apply jazz writing’s analytical approach to the coverage of popular music.

Gleason speaks with Bob Dylan in the mid-’60s (Photo from Gleason’s Facebook page, courtesy of the Gleason family)

Why do you think he was able to see in rock music what so many other jazz critics could not, especially his chronological peers?

He couldn’t help it. Gleason was caught in a paradox: every time he relieved his craving for new music, the craving returned. His teen discovery of jazz was so intense that he spent the rest of his life trying to re-experience the nirvana of drowning in music that shocked contemporary tastes. This overrode genre—if a song brought back the weird thrill of his ’30s jazz conversion, Gleason chased it.

Watch the John Coltrane Quartet on Gleason’s Jazz Casual in 1963

How was Gleason viewed by Jann Wenner and the rock-centric writers at Rolling Stone? Was he respected or treated as that odd older fellow going on about Duke Ellington?

Both. Wenner told me that Gleason was “old-fashioned” yet acknowledged his essential role in making Rolling Stone successful. [Rock journalist] Greil Marcus shared how he came to appreciate Gleason’s encyclopedic knowledge and integrity, even though Greil sometimes criticized Gleason’s later coverage of Bay Area rock.

What was Gleason’s most important contribution to rock journalism?

Gleason provided historical context for young readers because of his enormous knowledge of rock’s precursors—R&B, jump jazz and rock ’n’ roll. And when hybrids appeared like folk-rock, he had a deep understanding of the genres that were blended with rock and saw the logic in the combinations. For example, he quickly grasped how folk-rockers like Dylan departed from the Old Left ethos and racial discrimination of the ’50s folk revival that Gleason had covered.

I’ve always felt that Gleason was able to embrace San Francisco’s rock bands because they shared a love for improvisation with jazz artists. Would that be an accurate assessment?

I’ve always felt that Gleason was able to embrace San Francisco’s rock bands because they shared a love for improvisation with jazz artists. Would that be an accurate assessment?

As I dug deeper into Gleason’s views about individual San Francisco bands, I discovered a set of factors that predisposed him to like their music, including the use of extended improvisational solos. At first, he hardly mentioned the music at all—his early reviews focused on the milieu, the hair, clothing, dancing, attitudes, etc. Once he began writing about the music, he typically used jazz as a frame of reference: solos, ensemble work, swinging tempo, etc. Gleason covered jazz guitarists since the glory days of Django Reinhardt, and his favorite Bay Area musicians were guitarists like Jerry Garcia.

Listen: Gleason interviewed Jerry Garcia in 1967

Did he see a direct line from, say, Miles Davis to the Grateful Dead?

Gleason saw a parallel between modern jazz pioneers and leading-edge rock musicians. He was especially fascinated by how these innovators abandoned their genres’ traditional structures and experimented with new song structures that deviated from the old verse-chorus-bridge framework. Gleason also saw this de-structuring in experimental literature such as Beat poetry and Ken Kesey’s novels. The rock revolution, to Gleason, was part of a broader impulse in pockets of postwar America to shed oppressive rules and preconceptions and open up new possibilities.

Watch: In 1963, on his Jazz Casual TV program, Gleason commented on the state of the music

If you’re Ralph J. Gleason and you are at the Fillmore or the Monterey Pop Festival, what is going through your head as you watch Big Brother and the Holding Company or Cream?

“Here I am once again in the midst of another cultural renaissance!” But of all the scenes Gleason covered, the San Francisco counterculture made the greatest impression. Compared to the more subdued jazz and folk scenes, the Bay Area counterculture hummed with color, fantasy and tribal rhythms.

Watch: Gleason roll-calls a list that he compiled of late ’60s San Francisco rock bands

Gleason once had a public spat with guitarist Mike Bloomfield in the pages of Rolling Stone, where he basically accused Bloomfield of not being a true bluesman. What was that about?

Gleason wrote his column right after the release of the first Electric Flag album and Jann Wenner’s Rolling Stone interview with Bloomfield, in which the guitarist expounded on Black music. I still wonder what provoked Gleason to lash out. He had written highly complimentary reviews of Bloomfield’s playing at Fillmore shows earlier.

Related: Three films capture San Francisco rock’s glory days

Gleason firmly believed that, at best, White jazz musicians could only imitate Black jazz musicians. And so I assume this carried over to his views of White blues musicians. Gleason resented the fact that young rock fans idolized White blues-rock rock musicians without understanding the Black roots of rock. Gleason had watched the racial inequities of the music industry for three decades and was highly sensitive to it, especially White musicians borrowing the techniques of Black musicians and making more money than they did.

But something really irritated Gleason about Bloomfield in the spring of 1968. The column provoked a backlash. As I point out in the book, this was the start of Rolling Stone readers complaining about Gleason criticizing rock stars.

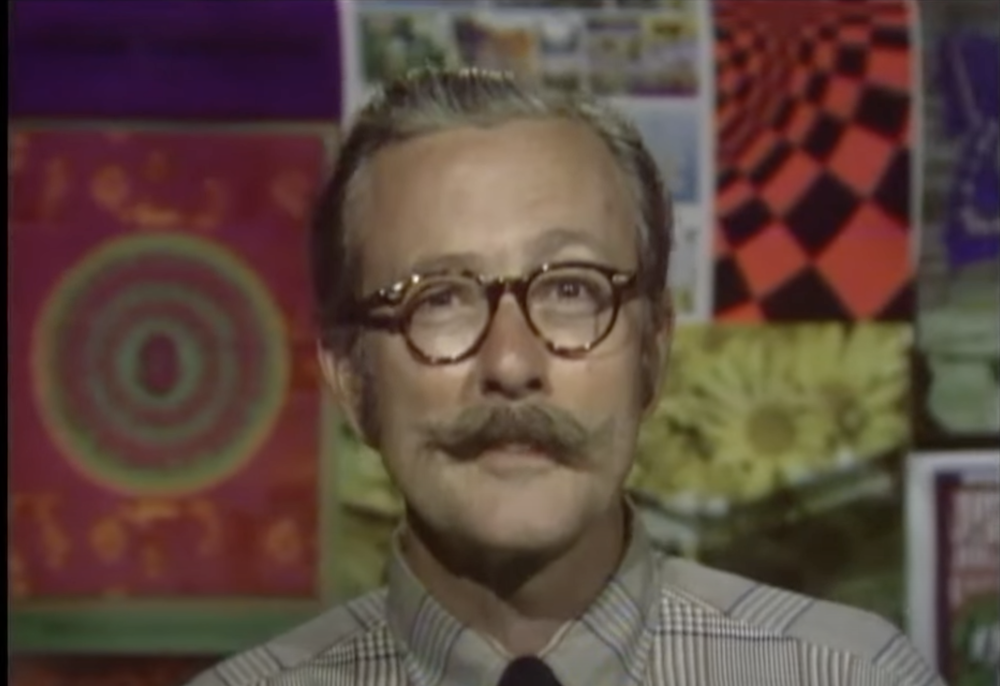

Ralph J. Gleason poses in front of a wall of San Francisco concert posters (Screen grab from 1968 film West Pole, YouTube)

Like many writers who covered the arts at that time, Gleason did not avoid commenting on the political and social climate of the day, and how that coexisted with the music. Was his take markedly different than that of some of the younger writers involved in the music scene of the day?

Gleason was part of the leftist intelligentsia that became politically aware during the 1930s. By the 1950s, that movement was called the Old Left, and a new one emerged called the New Left, which was more focused on civil rights and anti-colonialism. Inspired by writers like C. Wright Mills, Gleason embraced this new direction.

Free jazz musicians found a common cause with the New Left, and Gleason supported them. He also sympathized with Black radicals like Malcolm X, who other jazz critics condemned.

However, when the counterculture started in the mid-’60s, Gleason changed his view of the relationship between politics and music. After advising the new generation of Berkeley radicals in the early ’60s, Gleason didn’t like how that movement became more militant and how they tried to co-opt rock music. Gleason became what we would call a progressive today, part of the far-left wing of the Democratic Party. But he believed that it would be rock music, not politics, that would make America more progressive. This put him at odds with younger music writers who embraced militant activism.

Which chapter of the book do you consider most emblematic of who he was?

I think the final chapter and the Conclusion best show my theory of what drove Gleason.

What is Gleason’s legacy? Are there any critics today that have a viewpoint or an outlook, reflected in their writing, that is directly influenced by Gleason’s?

Mikal Gilmore and Greil Marcus are the first to come to mind. They have Gleason’s searching mind, looking for connections between the music they love and their broader interests. I’m very heartened by the recent generation of women and Black critics who, like Gleason, use writing to champion musicians who challenge stereotypes. Jessica Hopper, for instance.

What do you think he’d make of today’s music? To take a popular topic of this very moment, if Gleason were to write about Beyoncé’s country album, what would he say that, perhaps, no one else would even think of?

I ask myself that all the time. I think Gleason would love how Beyoncé deconstructed country music from a Black perspective. At the same time, he’d criticize anything he saw as an attempt to whiten her sound to appeal to a broader audience.

I can see Gleason liking what’s happening on the margins of jazz and rock—any music that’s expanding the vocabulary and shaking up the status quo. Or swings like mad.

Watch B.B. King perform on Jazz Casual in 1968

The book is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationWhen I was young and reading Rolling Stone mag, I always thought Gleason was about music and culture where Wenner was about money and fame.