The Paul McCartney Solo Debut: His Declaration of Independence

by Mark LevitonAs the Beatles stumbled through their final recording sessions in 1969, every member seemed to have a different view on whether they were about to break up, or had already done so. Maybe they were simply ready for a break from each other (and the often difficult job of being Beatles) and might continue to work together in the future? John Lennon had already asked for a “divorce” from the band, but didn’t specify when or how he might depart. As a business/management entity, the group had split into opposing camps, with John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr allied with hard-nosed New York businessman Allen Klein since May 1969, often clashing with lone hold-out Paul McCartney, who clung to his high-powered lawyers Lee and John Eastman, not incidentally his wife Linda’s father and brother.

In November/December 1969 McCartney went into self-imposed exile from the whole Beatles mess, spending eight weeks in Scotland at his farm High Park, with Linda, her daughter Heather (from a previous marriage to Melville See), and their newborn daughter Mary. Paul had already kicked around some original tunes with the Beatles that hadn’t found a permanent home, including “Junk” and “Teddy Boy,” and began to think more seriously about launching a solo career with an LP he could record all by himself.

Listen to the Beatles’ demo of “Teddy Boy”

Just before Christmas he and the family returned to their home in Cavendish Avenue, St. John’s Wood, London, and, as he later put it, he began to record with “a [4-track] Studer, one mic and nerve.”

McCartney didn’t have an overall plan in mind, and was happy to cobble together fragments of unfinished songs, ad-lib melodies on the spot and fiddle with instrumental experiments that owed something to his interest in the work of avant-garde classical composers John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luciano Berio.

He hid his plans from the other Beatles even as he worked with Harrison and Starr on their final recording, “I Me Mine,” in early January 1970. He took his home recordings to Morgan Studios in northwest London, bumping them up to 8-track to overdub some additional parts, like Mellotron strings for a second version of “Junk.” By late February he was at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios, where he recorded “Every Night” (another Get Back/Let It Be sessions reject), “Man We Was Lonely” and “Maybe I’m Amazed,” still playing all the instruments himself.

On April 9, 1970, McCartney had Apple Records execs Derek Taylor and Pete Brown send out a press kit “Q&A” for which Paul posed the questions and answered them, making it clear the Beatles were over; his new album affirmed his devotion to “home, family, love.” McCartney was released the following week, on Apr. 17, over the objections of Klein and the other Beatles, who were incensed that it interfered with the already-scheduled Apple releases of Let It Be and Starr’s Sentimental Journey. Lennon later dismissed the album as “rubbish.” Harrison praised several tracks, but also criticized it for its fragmentary, unfinished nature, saying McCartney’s lack of collaborators meant “the only person he’s got to tell him if the song’s good or bad is Linda.”

At just under 35 minutes in length, the album was certainly unambitious when compared to McCartney’s previous contributions to Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s, The White Album, etc., and that was clearly the point. This was homespun music that answered to no one else, a declaration of independence that made it to #1 on Billboard’s Top LPs listing, while underwhelming most music critics upon release.

Related: The #1 albums of 1970

Reviews with phrases like “sheer banality,” “no substance” and “second rate” were the norm, although most reserved some kind words for “Maybe I’m Amazed,” the most commercial and fully realized track. McCartney refused to release it, or anything else on the album, as a 45 rpm single, but airplay was copious nonetheless. When anyone thinks of McCartney’s debut they probably remember “Maybe I’m Amazed” first, despite it being placed as the second-to-last track on side two, normally seen as an LP’s dead zone.

The snippet “The Lovely Linda” begins the album before yielding to “That Would Be Something,” a bluesy, repetitive lope with minimal lyrics (“That would be something/To meet you in the falling rain”) and McCartney’s amusing, playful vocal scatting.

(Fun fact: Recognizing its roots in the blues, Jerry Garcia inserted the super-loose tune into 16 Grateful Dead shows in the 1990s, often paired with “Nobody’s Fault But Mine.”) The wordless “Valentine Day” follows, with McCartney doing some fine offhand work on electric guitar, dubbed over his acoustic, and some pretty good drumming.

Along with the other instrumental tracks “Hot as Sun/Glasses,” and “Kreen-Akrore,” it functions as something more than filler, although most fans probably ignore these instrumentals as “not real songs.” The heavy-drumming “Kreen-Akrore” which ends the album, by the way, was McCartney’s attempt at an audio tribute to the hunters of the Amazonian tribe he saw on a television documentary.

“Every Night” has a beautiful melody, nicely laid in bass and guitar tracks, and is sung quite well by McCartney, who fails to provide lyrics for the chorus and goes into a falsetto “woo-hoo-hoo” instead, to charming effect. “Junk” features glockenspiel-like struck wineglasses, very delicate guitar and bass parts, and what sounds like a percussion shaker or maybe a brushed snare drum. The lyrics are tenderly evocative: “Motor cars, handlebars/Bicycles for two/Broken-hearted jubilee/Parachutes, army boots/Sleeping bags for two/Sentimental jamboree.” A second version without lyrics, titled “Singalong Junk,” is included on the second side of the LP. Originally written when the Beatles were in India during 1968, it never found a place on one of their albums despite being demoed.

“Man We Was Lonely” is a countryish ditty which nods to Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash in its arrangement; one can easily imagine Harrison playing the slide guitar part. McCartney’s singing is engaging even when the lyrics aren’t much, and Linda interjects a couple vocal echoes.

“Oo You” is McCartney’s version of funk, cowbell to the fore. He’s clearly having a blast playing drums, guitar and bass like he’s at a bizarro Chuck Berry session. It’s got another freewheeling, improvisatory vocal with typical-for-Paul Little Richard touches, and flaunts its rudimentary lyrics with panache: “Look like a woman/Dress like a lady/Talk like a baby/Love like a woman.”

Announcing “rock and roll springtime—take one,” McCartney rips into “Momma Miss America” with drumming that recalls “Don’t Pass Me By,” bumping bass, tremolo-laden electric guitar and pounding piano. It falls apart in the middle and starts over with a different-sounding electric guitar solo over acoustic, has another false ending, and then McCartney goes all Jerry Lee Lewis on the piano as the cut crashes to an end.

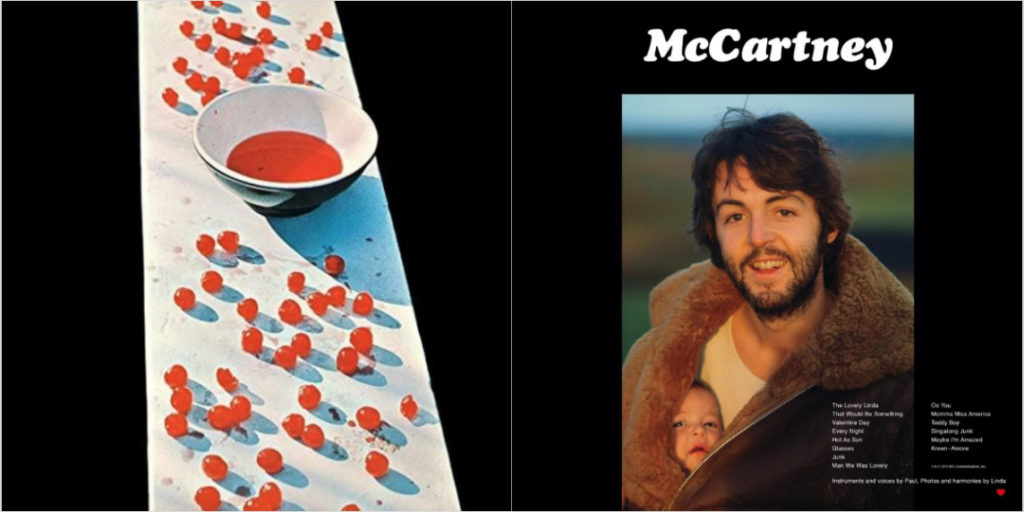

The 13-track album was wrapped in a striking gatefold sleeve, with a collage of Linda’s family photos inside, and two images that became especially iconic: spilled cherries on the front cover (without any type) and baby Mary tucked into Paul’s fur jacket on the back under the word “McCartney.”

Listen to “Don’t Cry Baby,” an outtake from the album

An expanded CD reissue in 2011 featured some unremarkable outtakes, a demo of a somewhat embarrassing tune titled “Women Kind,” and live recordings of “Every Night,” “Hot as Sun” and “Maybe I’m Amazed” from Glasgow, 1979. Successful as it was commercially, the casual McCartney was eclipsed by its follow-up, Ram, the following year. For some, the debut is merely a lightweight prelude to the last 50 years of McCartney’s extraordinary, varied solo career. It certainly has its moments, and contains some quite heartfelt sentiments about Linda and family life that with her untimely death in 1998 are all the more poignant. McCartney is a picture of Paul in transition, a historical document of quiet beauty.

Watch Paul and Wings perform “Maybe I’m Amazed” live in 1976

McCartney’s vast solo catalog is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. His post-Beatles career is the subject of a fine pair of recent books, The McCartney Legacy. They’re available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThis McCartney album was the end of the Beatles and a friendship. Very sad

Funny damned the critics, at the time I was 15 and I can well remember my friends and my older brother’s friends listening to it and thinking it was radical. The what we called lo-fi today was definitely refreshing in contrast to the very slick late Beatles recordings. Who starts an lp off with a short snippet of a song then there were the strange instrumentals that intrigued us. Then as for the songs we found none lacking each one of us snarling and trying to sound convincing singing along to Oh you and is ga ga golly goo goo lyrics, the lovely Junk and gentle Teddy Boy, the rolling rhythms of That Would Be Something, the throw back charm of Man We Was Lonely and the awesome Maybe I’m Amazed. The lp sound like no mainstream lp we had heard,so the critics at the time didn’t get it but they didn’t get the masterpiece Ram either but time has put the petty post Beatles fractions behind us and the music is still the same great music it has always been.

I’d like to see the critics write something half as good as “Maybe I’m Amazed.” We’ll wait…

I think it’s the only good song on the album. It’s one of the best that McCartney has ever written. Borrowing words of John Lennon, the others are just muzak to my ears!