Seeing It Said: Confessions of a Former Nick Drake Fraud

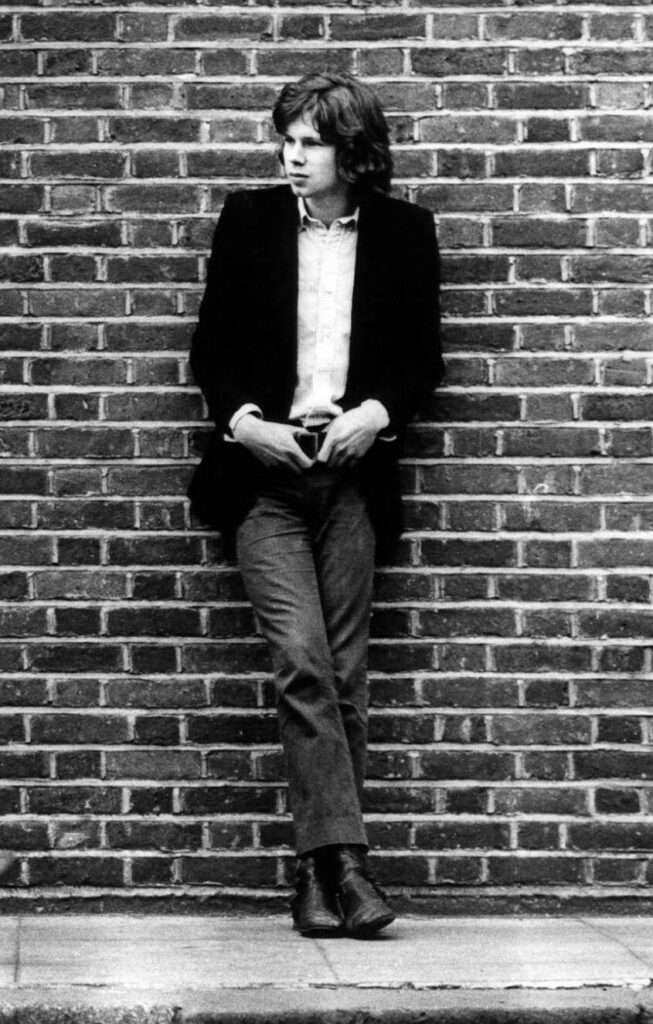

by Colin FlemingOn Nov. 25, 1974, Nick Drake, age 26, ingested a deadly amount of his antidepressant, went to bed, and never awoke again. He left behind three albums, a handful of additional tracks, a talent he believed he had lost, and the pain he could neither escape nor overcome.

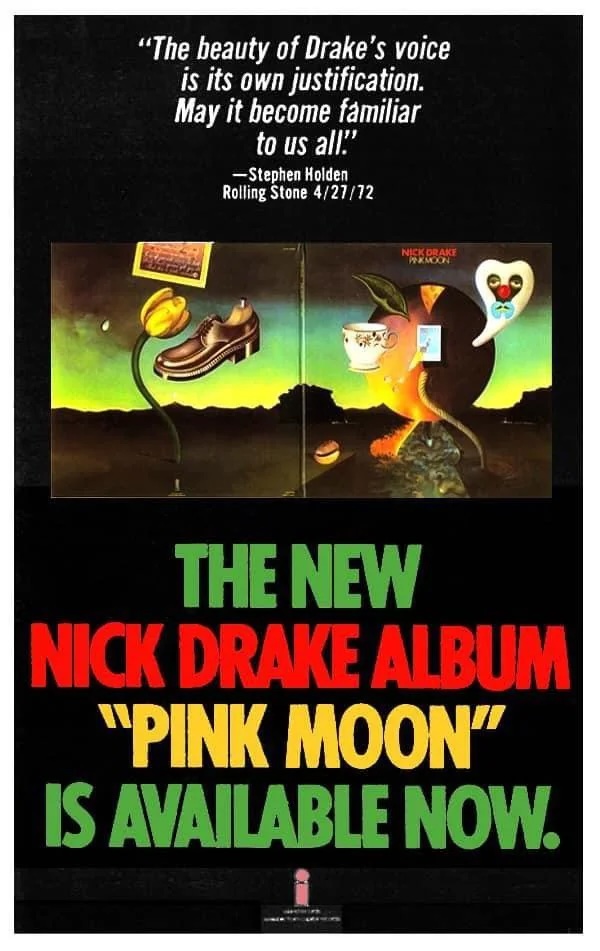

Five years later, his music began to gain traction in a manner it never had during his lifetime, thanks to the release of the Fruit Tree boxed set, containing what was thought to be Drake’s entire recorded output. This was a time when encountering outstanding music that had eluded most of the public was a key part of what loving music was all about. One lived for these discoveries and the conversations in record stores that emerged therefrom. Those Nick Drake albums—Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971), Pink Moon (1972)—were played, shared. They became records of the cognoscenti. It was cool to know about Nick Drake. No one sounded like him. He was his own and his lone frame of reference.

The vocals were akin to the advice of a friend who had leaned in close to convey words of grave importance, but gently, in audible textures of gossamer. Then there was Drake’s rarefied level of accomplishment and artistry with the guitar. Everyone knew the obvious virtuosos—Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton—but Drake may have been better than all of them without a single solo in his oeuvre. He pulled off that rarest of feats one may have experienced with Robert Johnson and conceivably nobody else: Which is to say, causing a listener to wonder how that could possibly be only a single person with a six-stringed instrument and two hands.

Related: The year 1970 in rock music

In terms of content—both narratively and imagistically—here was the stuff of the darkest nights of the soul, the bracing hours of being alive, but shot through with the pastoral. Even Drake’s musical cityscapes were as autumnal as the leaves falling from the trees in some copse through which John Keats may have passed.

Listen to the title track from Pink Moon, Nick Drake’s final album

I was someone who claimed to be very into the music of Nick Drake. I played his records, but in what amounted to an empty exercise of trying to give myself a form of credit for my good taste. It felt like one should listen to Nick Drake, based on what was said about him. I’d play the music—which is to say, merely have it on, as if in time and through aural osmosis I’d “get” what Drake did, a method of partaking which is less suited to Drake’s music—and his brilliance—than with perhaps any other popular music.

For what I had yet to learn is that presence is what the art of Nick Drake asks of us. Our total presence. That’s what it needs from us, in order for us to get what we need from it. And so for many years I missed out on that art because I was a Nick Drake fraud, until the music contained on his final album, in particular, became the art that became a part of me.

I think there are a lot of people who are Nick Drake frauds. I’m not trying to be captious or accusatory. It can feel easier sometimes just to say words rather than mean them, never mind that we’re making things harder by keeping ourselves from what otherwise would be our rewards.

It’s easy to go with an accepted flow and there’s certainly a well-fed legend of gloom behind Pink Moon. Upon its release in 1972, many of Drake’s friends and family members said they didn’t like it. The LP was too painful. Why would anyone wish to listen to that much suffering?

Drake’s own parents—who were as supportive of their son as any mother and father can be—later remarked that they only had the heart for one song on the album, that being its concluding number, “From the Morning,” which is pitched in an uplifting emotional key, the idea of rising rather than falling. It’s a clarion call to stand up and move forward, but just because one falls into Pink Moon—as if terra firma and the night’s sky has been turned upside down—doesn’t mean one is descending into misery and defeatism.

If you don’t open yourself up to Pink Moon, it’s apt to feel so personal—even, paradoxically, from a distance—that you make the mistake of concluding this isn’t a work of universal utility. Stuff for us all, to help us all. It’s tempting to try and align ourselves with what we think of—or want or need to think of—as this unremitting edifice of pain. I get it, we wish to inwardly intone. For I too, have suffered.

If you don’t open yourself up to Pink Moon, it’s apt to feel so personal—even, paradoxically, from a distance—that you make the mistake of concluding this isn’t a work of universal utility. Stuff for us all, to help us all. It’s tempting to try and align ourselves with what we think of—or want or need to think of—as this unremitting edifice of pain. I get it, we wish to inwardly intone. For I too, have suffered.

Who doesn’t think their pain runs deep? You don’t want to feel alone in that regard. We seek kinship. The manner in which Pink Moon was discussed, and also what I suspect is the way in which most people listen to it, resulted in many people who treated the record as this pain-based badge of honor, missing out—for a time being, anyway—on what was actually happening within the life-bolstering grooves of that record.

A day came when I put Pink Moon on while not doing anything else. It just seemed like I was ready for something to hit me hard and correctly. Ready to listen openly. I wasn’t reading, I wasn’t working. I was, with this record—for the very first time, despite Pink Moon being an LP I had likely given 500 spins.

And what I heard was the most uplifting music of my life. Music that was filled with life. A deathless spirit. Deathless beauty. Deathless vision. An unwavering life-force, despite—or perhaps because of—what its creator knew about life. I thought, “This is a celebration, not a dirge. Like a miracle of humanness.”

Being present is often a challenge, especially in our world. How often are we ever engaged and focused without distraction? A listener needs to be fully present with Drake’s Pink Moon. It gives so much to that person, but only if the person gives something of themselves first.

The album was cut in two late-night sessions. Save for a piano overdub to the title track, Pink Moon is just—there’s a misleading “just”—Drake with his guitar. He felt that the string and horn arrangements on his first two records put a needless layer between himself and the listener. With Pink Moon, he wanted to give of that self, as freely and richly as possible. No barriers. Me to you. And us to the world.

That’s the uplift—the elevating—we get with “To the Morning”: “And now we rise/And we are everywhere/And now we rise from the ground.” The singer means those who have heard and understood what is in this record, which is itself not confined to a disc or a single work or creation. We’re going out into the open with Pink Moon. We’re venturing into life.

No record seems to lean further into the world with its opening lines than does Pink Moon. “I saw it written/And I saw it said,” Drake sings, but this is more than singing. The voice has that sweep of the eternal, in which all will be conveyed; everything can be found here, provided one knows how to look, listen and receive. And yet it’s a reified voice, as if forever corporeal, a voice of one who walks behind, helpfully and hopefully at our back, wishing to see us progress. To keep advancing. Or begin.

The record comprises “only”—again, a misleading notion—28 minutes of music, but a result of the temporal brevity—and the giving quality of the art—is that as soon as Pink Moon finishes, the listener who was fully present has the urge to start with the beginning once again. You keep at it. It’s hard to walk away from Pink Moon. And when you do, you take it into your day with you, your existence, your self.

I find it impossible to listen to the likes of “Which Will” without crying. These are tears of gratitude. That someone could be this wise, this selfless, and impart those attributes in a song that helps us become wiser and a bigger help both to ourselves and others.

The song is about wanting to see another person be well, no matter what. Full stop. Regardless of if the singer of the song isn’t loved back by that individual. Goodness isn’t about reciprocity. It’s an absolute, which is absolutely plain on Pink Moon.

As Drake entered the portion of his life that would take him out of this world, he had insights for those who remained, and those who would come. The singer of this song—and I’m hesitant to say it’s Nick Drake, that man with that name who was born in that year and died when he did—has a knowledge that can be hard to locate on our own, if we ever do. You want to get to where Pink Moon is. It’s something to shoot for as a human.

Pink Moon amounts to a giving. You can’t make someone take a gift, though. Sometimes they don’t know that they’re being offered one. All of those years and this bestower of an album was playing on my stereo, and there I stood in place, creating silly theses in my head, that here was a record of the greatest suffering, like this book and that poem and that film.

A friend of a friend’s daughter took her life last year. She was 14. Died the same way that Drake died. My friend’s kid was understandably inconsolable. And scared. She was being picked on at school like her late friend and feeling not only lost, but that your worst fears could actually come true and it wasn’t that rare after all and death gets up closer to us than we think.

I wrote her a note, and I said, “There’s a record by a man named Nick Drake, and people say it’s too painful, and I used to pretend that it was, but then I started listening to it, and it really helped me, it helped me keep a light on in my heart, or make that light burn brighter. It’s called Pink Moon if you want to try listening to it.”

And she did. She kept listening. And it helped.

Helping is a function of Pink Moon. I think that’s what the best art does. It makes us a loan of some of its life, and then says, “No, you keep it, and here’s some more, too, if you like.”

The chorus of “Which Will” comprises nine words, each a syllable in length: “Tell me now/Which will you love the best?”

To the best of your ability to love. Not best as in first-in-show. But love with all that you have, all that you are.

That’s how Nick Drake made his music, which is itself that manner of love. Give something of yourself to that music by being present with it. What it will give you back is the greatest of all gifts: The most human of lights for which there is no dark night that it cannot penetrate.

Listen to a rare home recording of “Place to Be” from Pink Moon

Drake’s recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Drake’s “Northern Sky” was featured in the 2001 feature film, Serendipity.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.