New Riders of the Purple Sage’s Debut LP: Country + Rock + Jerry Garcia = ?

by Jeff Tamarkin Although the New Riders of the Purple Sage are often grouped among the pioneering country-rock bands of the late ’60s and early ’70s—Poco, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Sweetheart of the Rodeo-era Byrds, and Bob Dylan himself with his John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline albums—theirs was a different undertaking. While country and rock did indeed reside at the core of their sound, anchored by pedal steel guitar and the twangy fretwork of lead guitarist David Nelson, NRPS—as their name has always been abbreviated—was born of another sensibility, one that shared much with their friends and mentors the Grateful Dead.

Although the New Riders of the Purple Sage are often grouped among the pioneering country-rock bands of the late ’60s and early ’70s—Poco, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Sweetheart of the Rodeo-era Byrds, and Bob Dylan himself with his John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline albums—theirs was a different undertaking. While country and rock did indeed reside at the core of their sound, anchored by pedal steel guitar and the twangy fretwork of lead guitarist David Nelson, NRPS—as their name has always been abbreviated—was born of another sensibility, one that shared much with their friends and mentors the Grateful Dead.

Like the Dead, the origin of the New Riders (the other shortcut to their name) is traceable directly to the folk music scene centered in the Peninsula, the region south of San Francisco encompassing San Mateo and Santa Clara counties, in particular the city of Palo Alto and the student-occupied neighborhoods near the campus of Stanford University. During the early ’60s, the Peninsula (home of Joan Baez) was a hotbed for aspiring folkies and bluegrass connoisseurs, many of whom—banjoist/guitarist/vocalist Jerry Garcia, singers/songwriters/guitarists David Crosby, Paul Kantner and Jorma Kaukonen and others—traded ideas as they worked the local clubs for whatever small fees they could scrounge.

By 1965, with the advent of the Beatles, the calling of rock and roll was too tempting to resist: Crosby was already going strong with the Byrds, who scored a #1 single covering Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man”; Garcia had co-founded a band initially calling itself the Warlocks (soon to become the Grateful Dead); and Kantner and Kaukonen had just launched (along with singer Marty Balin) a rock outfit they called Jefferson Airplane.

It would be a lie to say that the rapid ascent in popularity and the ubiquity of the hallucinogenic LSD in the Bay Area had little effect on the boundless expansion of the music these folks and their colleagues were making: the Peninsula and San Francisco itself served as ground zero for the psychedelic culture that began shifting from well-kept secret to international phenomenon during this time, luring thousands of young people to the area; the freedom to experiment that these musicians enjoyed while performing at venues like the Fillmore Auditorium and the Carousel Ballroom in the city allowed them to take their music in any number of new and unexpected directions, but also to call upon their roots in acoustic music.

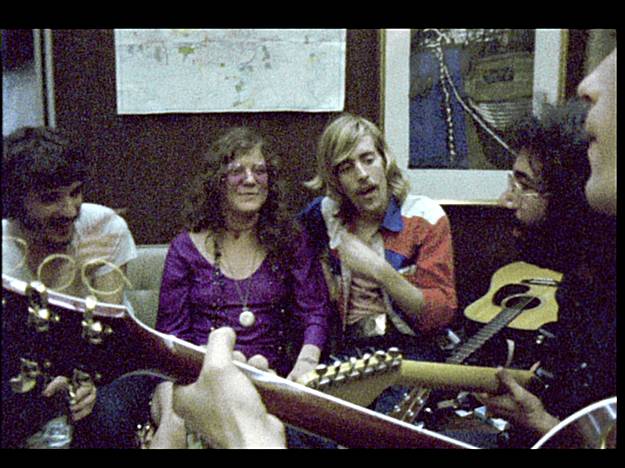

New Riders of the Purple Sage, 1970 (l. to r.): David Nelson, Jerry Garcia, John “Marmaduke” Dawson, Mickey Hart, Dave Torbert (Early promotional photo)

By the end of the heady decade, numerous rock bands, most based either in the Bay Area or the vicinity of Los Angeles, looked to country music as a refuge from the sizzling, cranium-searing electricity of what was being labeled acid-rock or psychedelic music; a newly emergent back-to-the-land movement (“Let’s live on a commune in the desert and grow alfalfa!”) and a desire to simplify life seemed to go hand in hand with the lonesome sound of steel guitars, fiddles and songs touting the richness of a rural, less encumbered lifestyle away from the clatter of the city.

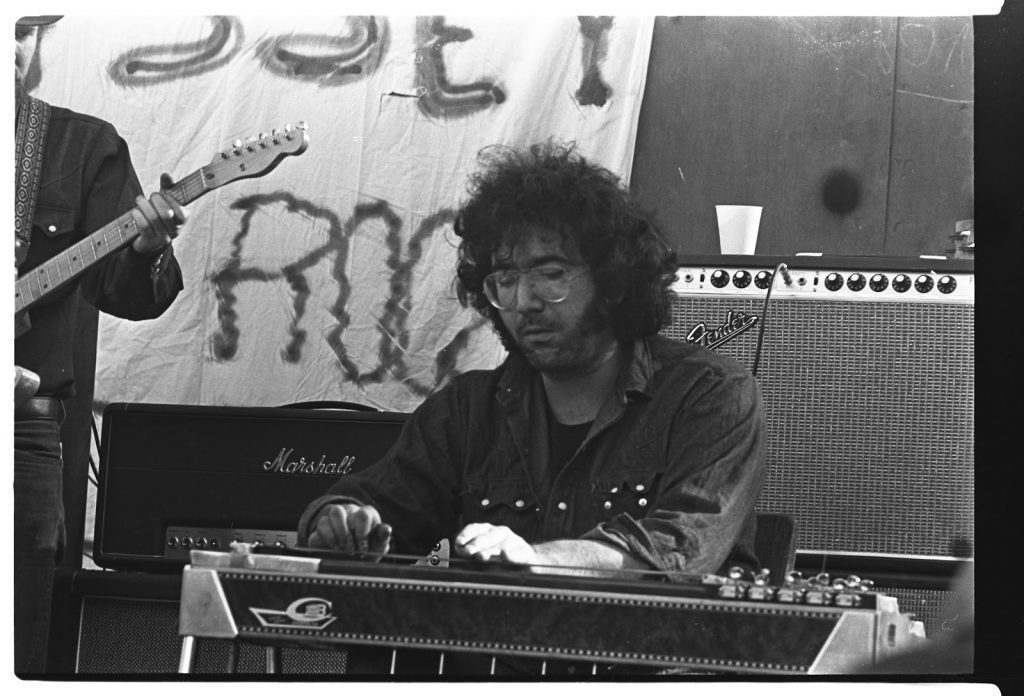

The ever-restless, hyper-prolific Garcia counted himself among those looking for new outlets. Although the Dead were arguably at their most experimental and electric at the time, he began learning to play the pedal steel, an instrument inextricably associated with country music. He incorporated it into Dead concerts but that avenue didn’t allow him to fully explore its potential. For that, he teamed up with his Peninsula friend Nelson, who had been keeping busy with a group called the New Delhi River Band, and singer-songwriter John Dawson, who went by the nickname Marmaduke. Working up songs largely authored by Dawson, as well as some choice covers, the trio requested assistance from Dead bassist Phil Lesh and drummer Mickey Hart and morphed into the New Riders of the Purple Sage, taking their name from the 1912 Western novel Riders of the Purple Sage by Zane Grey.

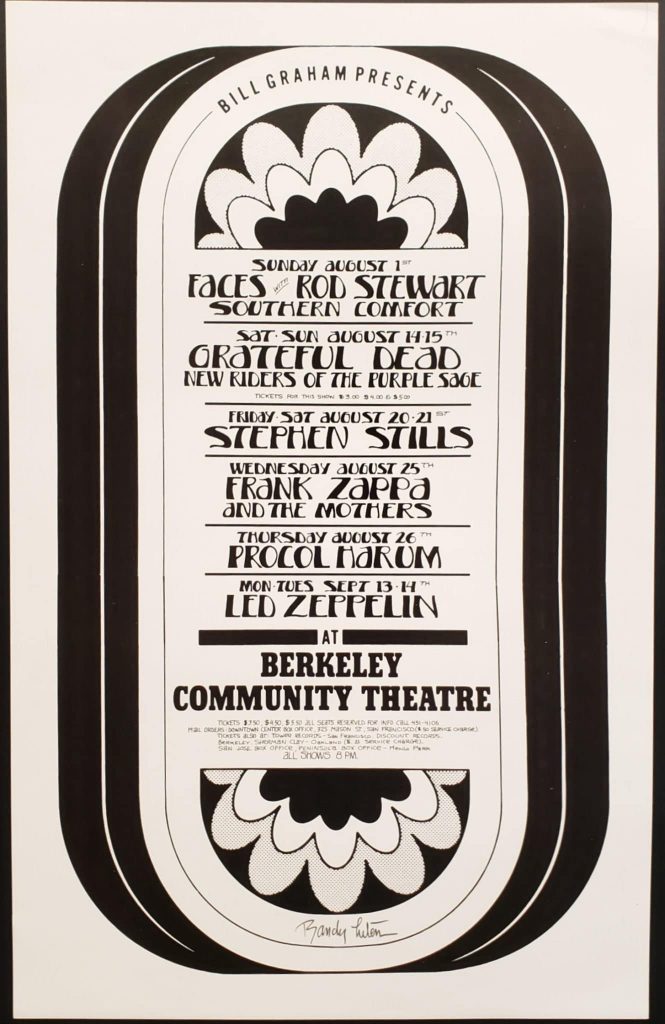

With Dave Torbert (who had also been a member of the New Delhi outfit) replacing Lesh on bass, the quintet began gigging around the Bay Area in 1969 and, by the spring of the following year, opening for the Dead on tour. A typical gig of the period might find the Dead beginning a concert with an all-acoustic set, followed by the New Riders and finally the electric Dead: with Garcia participating in all three configurations, he might keep busy onstage for upwards of six or more hours during a given evening.

From the Festival Express documentary (l. to r.): Rick Danko, Janis Joplin, John “Marmaduke” Dawson, Jerry Garcia, in 1970

As the New Riders gained in popularity in their own right, and with the Dead finding a wider audience via their acoustic-based 1970 albums Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, it was not long before record companies began sniffing around. Columbia Records, helmed at the time by the renowned Clive Davis, signed the group and they went into San Francisco’s Wally Heider Studios toward the end of 1970 to record their debut album, self-producing with the help of engineer Stephen Barncard. They ultimately laid down 10 original Dawson compositions that varied in style and temperament, drawing nearly all of the songs from their live setlists.

The album, self-titled, was the only official NRPS release to feature Garcia on pedal steel, and as such it serves as a shining example of his uncanny ability both to absorb the traditional techniques of the Nashville masters and—with his head still fully immersed in the psychedelic world—to find new mind-bending means of expression on the instrument that virtually no one else had ever considered.

There would be one more personnel change as the album sessions were underway, however: Drummer Hart was out (he also left the Dead for a period of four years), and Spencer Dryden, who had driven Jefferson Airplane during that band’s prime years of 1966-70, was in. He proved a better fit, a steadier, more rock-solid sticksman than Hart, less prone to tossing in offbeat, sometimes ill-considered percussive accents. Hart appeared on two tunes, “Dirty Business” and “Last Lonely Eagle,” both of which also featured pianist George “Commander Cody” Frayne, the leader of the rising local band Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen’s debut

For all of the color that Garcia brought to the sound, though, there is no doubt that Dawson was the primary creative force of the New Riders of the Purple Sage. As sole composer and lead vocalist throughout the album, this was his vision. The album’s lead track, “I Don’t Know You,” also served often as the opening number during the group’s concerts. A melodic, uptempo rocker, it tells a simple but mysterious tale of a woman appearing in the protagonist’s life unexpectedly, or maybe not: “I don’t know you, you’ve been lately on my mind,” sings Marmaduke as Nelson and Torbert join in harmony, but soon after he’s telling another story: “Come sit beside me, I’m not sure if you’re still there.”

“Whatcha Gonna Do,” which follows, slows the pace, the singer again musing on a woman of no fixed presence: “Where you gonna go on the planet today?” he asks to a springy rhythm, then leaves her appearance to chance: “Take a look around ya now and what do you see?/If you could go somewhere’s else now, where would that be?/When you find a place to hide, come and tell me where it is now/I’ll still be sitting here, singing in the air.”

A longtime staple of the band’s live shows, “Portland Woman” is an oft-told—but usually not quite as frankly—tale of a traveling musician’s yearning for temporary companionship: “If I don’t find someone tonight, I just won’t make it through,” Dawson laments. Mission accomplished, he heads back out on the road the next day, but this time he’s having second thoughts: “The little girl that I had found, her I left behind/But I haven’t felt too good since I left Portland yesterday/I’m going back to Portland town now, what more can I say?” he sings with longing and firmness in his voice.

Another NRPS perennial, and a guaranteed crowd-pleaser, was “Henry.” Whereas most pro-drug-related songs of the era still attempted to be cagey, Marmaduke was having none of that. “Henry” is an unabashed tribute to a high-volume smuggler of weed heading toward Acapulco, then back to the States through the rugged mountains of Mexico, to the “50 people waiting back at home for Henry’s load.” One of the speedier songs on the album—reflecting Henry’s “fast, fast, fast” driving down the “twisty mountain roads”—it was always a fun romp, packed with crisp country licks from Nelson and a playful, bluegrass-y pulse from the rhythm section, that gave the band’s toke-happy fans an opportunity to celebrate a very different kind of outlaw than those usually found in country tunes.

“Dirty Business” is the album’s most unorthodox tune, a showcase for the extreme sounds that Garcia had already discovered he could get out of his pedal steel. At times taking it so far from country music as to be nearly unrecognizable—haunting, eerie, unsettling, just plain nasty—his performance here is the epitome of his visionary approach to the instrument. Garcia gives the ballad a sense of foreboding and dread that its lyrics—of the “dirty business” perpetrated behind the scenes at a coal mine where frustrated workers and management are at odds—desperately call for.

An age-old country music standby—that of the great train robbery—is next. “Glendale Train”—which reprises the band’s favored stepped-up bluegrass tempo and features Garcia returning to the banjo, which he played during his Peninsula days—is one of several tunes on the recording that find the Dawson-Nelson-Torbert trio engaging in harmonies that hew closely to standard bluegrass while veering just far enough away to remind us that this is no run-of-the-mill country-rock band. Nor is this a tale with a typically happy good-guys-win ending: Pity poor Amos White, the baggage man, for his is not a fate any honest workin’ man deserves.

In 1971, songs warning of impending environmental cataclysm were few and far between, but in “Garden of Eden,” Dawson was on it. The “cool clear water ain’t quite as cool and clear as it ought to be,” he proclaims, and there’s “smoke fillin’ everywhere.” We “live in the Garden of Eden,” he reminds us, “don’t know why we want to tear the whole thing to the ground.” Sad to say, those who could do something about it didn’t—the song, despite its pretty melody, is just as relevant today as in 1971.

“All I Ever Wanted” is a thing of beauty, a tender, sensitive love song which gives Garcia an outlet to display the most tear-jerking sounds that can be coaxed from a pedal steel guitar. Marmaduke’s keening vocal performance can’t exactly be called a croon, but the soft edges he brings to the lyric—how much more to the point does it get than “All I ever wanted was your loving?”—define the sound of affection.

It’s followed by “Last Lonely Eagle,” one of the most powerful songs on the album and another that was years ahead of its time. With stellar vocal harmonies driving the appropriately uplifting chorus, and a sense of drama balancing out its discomfiting message, Dawson writes of those who’ve “forgotten their dreams and they’ve cut off their hair” (hello, David Crosby!), while imploring us to “Take a last, flying look at the last lonely eagle/He’s soaring the length of the land/Shed a tear for the fate of the last lonely eagle, for you know that he never will land.”

Finally, there’s the stomping “Louisiana Lady,” in the grand tradition of road warrior trucker tunes like Dave Dudley’s “Six Days on the Road.” In this variation, our intrepid traveler has been on the road for a full week, “so beat my vision’s just a yellow haze.” If he pops a little speed and drives faster, he can cut an hour off the time on his way to New Orleans, where “it’s gonna be worthwhile, I’m gonna see my lady smile.” Another crowd-rouser in concert, the song, like several of its predecessors, features stunning harmony and a vibe that’s somewhere between hardcore hippie and good ol’ American tradition, a perfect sendoff.

Released in August 1971, the album featured, on its cover, the band’s striking red, white and blue, and orange and gold, logo—a green cactus standing tall at its center—that would become familiar to all of its fans. Although not a huge hit, the LP peaked at #39 in Billboard and helped establish the New Riders as an entity apart from the Grateful Dead, although they would continue to open shows for the more successful band for years, even while touring on their own. By the 1972 followup, Powerglide, Garcia would bow out of the group, concentrating full-time on the mothership, replaced by Buddy Cage on steel—the band had seen him performing with Canadian folkies Ian and Sylvia during the 1970 cross-Canada Festival Express that was later featured in a documentary of the same title.

Related: A 1976 interview with Jerry Garcia

Sadly, all but one of the key members of the 1971 New Riders—Garcia, Dawson, Torbert and Dryden—have left us. Only Nelson survives, still leading a NRPS group while also performing with his own David Nelson Band. While NRPS is only rarely lauded in the same reverent tones as the groups that featured the also-deceased Gram Parsons, or even the early Eagles, they nonetheless broke through barriers, taking a different approach to the country-rock hybrid than anyone else. Their debut album remains an invigorating, prescient listen more than 50 years after its release.

Watch Jerry Garcia rehearsing with NRPS in 1971, from the 1972 film Fillmore

9 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI feel to be so blessed to have been a young man in the 60’s with the magic of the Bay Area and the incredible music available practically every night in SF and surrounding areas. It’s cliche, but you really had to be there. It lives on in my dreams and memories.

What a great album. Really enjoyed the article. Thank you

As a freshman in college and an aspiring guitarist, I lived and breathed NRPS.

Thanks for doing this, Jeff.

I can’t believe it took me this long to write about this album!

next mission: write about marc benno..

but i’ll read whatever you write…

Trip down memory lane, Jerry and these musicians still live on with the magic that they created so long ago. I remember going to those shows, they really were that good. Gonna go put the album on the record player and try to remember what caused each scratch…..

Nice piece

Loved the band so much I named our family dog Henry. My brothers and I had a great laugh years later when we told mom & dad where his name come from.