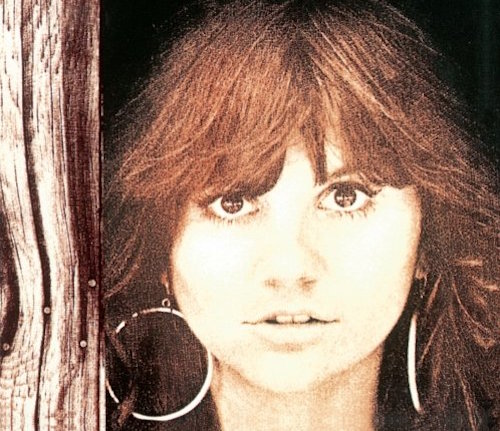

Some time in the late 1990s, Linda Ronstadt began to notice that singing was becoming more difficult for her. She recorded her final album—the Grammy-nominated Adieu False Heart, a duets set with Cajun singer Ann Savoy—in 2006, and gave her last concert in 2009. Two years later she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease and, in 2013, she made her condition known to the public. That same year Ronstadt, born July 15, 1946, published her autobiography, Simple Dreams: A Musical Memoir. [It’s available here.]

Best Classic Bands editor Jeff Tamarkin spoke at length with Ronstadt that year, but only a small portion of the interview was published at the time. Here, in two parts, we present the complete, unedited interview.

You wrote in your book that music shouldn’t be delegated to professionals. What did you mean by that?

I really like live music. People ask me what records I listen to at home and the dirty little secret is I hardly listen to any records, ever. I do go out to hear live music, and musicians come over here and I play music with them still. I don’t sing anymore and I can’t play the guitar but I’m involved in their music and I still feel like an active part of it. People ask me how I cannot like recorded music when I’m a recording artist but all of the recorded music I did was a live experience for me and then I never listened to it again after that. There are wonderful recordings and I’m glad we have them; they’re things that I treasure—Ray Charles recordings and Ry Cooder recordings, and especially classical music. I love to listen to Maria Callas and I’m glad we have her recordings because we don’t have her anymore and I can’t run out and hear her live. But mainly I prefer a less illustrious live performance—whoever is playing at the San Francisco Opera may not be as big a star as Maria Callas but they’re doing a really good job and I like to see it.

Did it come naturally to you to write an autobiography?

I’ve never written anything. I never wrote a journal or a diary, and I only had one letter that my parents had saved—it was a story about the Doors that I wrote about in the book, chartering a DC-3 and what it was like. Otherwise it was from my memory, which is failing. I had to check with everybody and ask, “Do you remember it this way?” I had a good copy editor who checked dates and stuff like that. Otherwise I’d have people dying way before they ever had children.

Linda Ronstadt on Playboy After Dark

Did you do any research on your own past?

I don’t know how. I had [producer] John Boylan, who’s good at researching, look up dates. My copy editor was incredibly good at checking dates, though he told me that it was one of the cleanest manuscripts that he’d ever gotten, which made me pretty happy. It was my Catholic school grammar training.

What is your favorite story in the book?

The funniest, silliest story is when I was walking down the street with Randy Newman and he nearly got us both shot by the police.

Do you remember the first music that had an impact on you?

It was probably two records—the Trio Calaveras on 78 and the other was La Niña de los Peines’ Pastora Pavón. She was a flamenco singer, considered the greatest of the 20th century. My father’s sister had brought the flamenco records back from Spain and the Trio Calaveras records from Mexico, and I just remember when I was 1 or 2 years old watching that record spin around at 78 RPM and listening to those songs and they just blew me away. They had an incredible impact on me.

How old were you when you knew you would be a professional singer?

I never knew, one way or the other, if I could sing or not sing or be a professional singer. I just sang. There’s a real difference between that, and I don’t know how to explain it. I just couldn’t stop singing. I knew that I was a singer. I didn’t know that I was a star or that I was successful or that I was a professional. When I was 6 years old, or even 3 years old, I knew I was a singer.

But at some point you said, “I’m going to make a go at doing this for a living.”

Well, I was already in a little group with my brother and my sister, so I just felt that I could do that again. And it was really just because Bobby Kimmel, who was in our little group, had already gone to Los Angeles and he said, “Come on, we’ll make our own group and I can get us work.” So, fine, I went to work in a pizza parlor and a beatnik bar and a bar someplace where I had to lie about my age. I also had to add a few years to my age and I did it so much that after a while I got to be 50 before I was even 45. Some people lie about their age in one direction and I went in the other. [laughs]

Why did you choose to become an interpreter and not a songwriter?

I didn’t decide. I just wasn’t a person who woke up every morning and wrote a song. Karla Bonoff woke up every morning, and spent time writing a song. Some are better than others. Dolly Parton does that; she writes eight million songs a month. Some are good and some are just the songs she wrote that day. Sometimes a song would just come out and there was nothing I could do about it; it just came out of me. But the only song I ever wrote on purpose was “Winter Light,” with Eric Kaz. We wrote that together.

How did you know when a song was right for you?

How did you know when a song was right for you?

Something resonates. I read a poem last night that does exactly the same thing. I go, “That’s telling my life. That’s exactly how I feel.” When I heard “Simple Man, Simple Dream,” J.D. Souther’s song, where it says, “What if I fall in love with you just like normal people do, well, maybe I’d kill you or maybe I’d be true,” I knew I had to sing that. Those lines are so brave and so original and true because you just never know. Romantic love is treacherous, and sometimes you’re the treacherous one and you’re not even trying to be. Sometimes you’re trying as hard as you can just to be as nice as you possibly can and as honorable as you possibly can, and you just kill somebody. Or they do it to you—sometimes they’re trying to get you. It’s a tremendous risk.

Did your producer and manager, Peter Asher, ever choose the songs?

Oh, never. He had plenty to do, believe me. He was an excellent record producer and he was a great troubleshooter and he really knew how to organize things and keep things moving and get the best out of the musicians. I did a lot of the arranging myself and the musicians contributed a tremendous amount to the arrangements. Peter was good at hearing the ideas and he could recognize the better ones and string them on a thread. That’s what a good producer can do. And Peter was very well-rounded. He was a child actor in both theater and movies—his sister Jane is of course a very famous actress in England. He is also a big reader and knows a lot of different kinds of music. He didn’t know American standard songs and that whole catalog, or about Mexican music, but when he heard it, he thought it was good.

Watch a favorite that Asher produced for Ronstadt

Did you ever get songs from demo recordings?

No, I rarely got a song from a demo. I think I got “The Blue Train” from a demo. Emmy [Emmylou Harris] brought it. No, I’d just be hanging out and maybe Waddy Wachtel would play an Everly Brothers song or J.D. Souther would play a song. I’ve got a tape of Jackson Browne teaching me “Poor Poor Pitiful Me” and trying to talk me into singing it. We had to change the words around a little bit and that was the same night that J.D. Souther taught me “Blue Bayou.” He said, “You ought to do this song,” and I said, “Yeah, that’s a really good song.”

Related: Linda Ronstadt rocks Warren Zevon’s “Poor Poor Pitiful Me”

Several times in the book you say you didn’t sing a song very well.

Music to me is always a work in progress, and things are frozen, especially in the early stages when I’m just learning it, just climbing around in the rigging and trying to check out the architecture of the song. Then we’d play it night after night and refine it, and I’d learn how to really phrase and I’d be flying around without even thinking about it, like it was nothing. After about three weeks on the road, that’s what it turns into.

When did you become confident in your singing?

It was after 1980. When I went to Broadway and did the Nelson Riddle stuff [Ronstadt recorded three albums with arranger Riddle], I learned a tremendous amount. Then, doing the Mexican stuff I really learned even more. I was able to expand my voice and do a lot more. By the time I got to Frenesi [Ronstadt’s third Spanish-language album, from 1992], I could learn stuff and just do it. Even still, the recordings were the beginning process, especially with the Mexican songs, because the rhythms are fiendish and extremely difficult. I had known them ever since I was a little child and that’s what saved me, but it’s really hard to learn that stuff. Sometimes I had to learn the dance steps to learn how to phrase it. The Mexican stuff was harder than anything else I ever did.

What do you listen for in other singers?

They have to have a story that is so urgent that I have to listen. Someone says, “You have to listen to this because this happened to me and it was so hard and I’ve got to tell somebody about it and I need you to listen.” Regardless of whether I’ve had that experience or not, I can live through their experience and learn from it. It’s like reading a great novel. Literary fiction, as opposed to popular fiction, they say, increases your emotional intelligence and your ability to empathize. A really good song and a really good singer demand that you empathize with them.

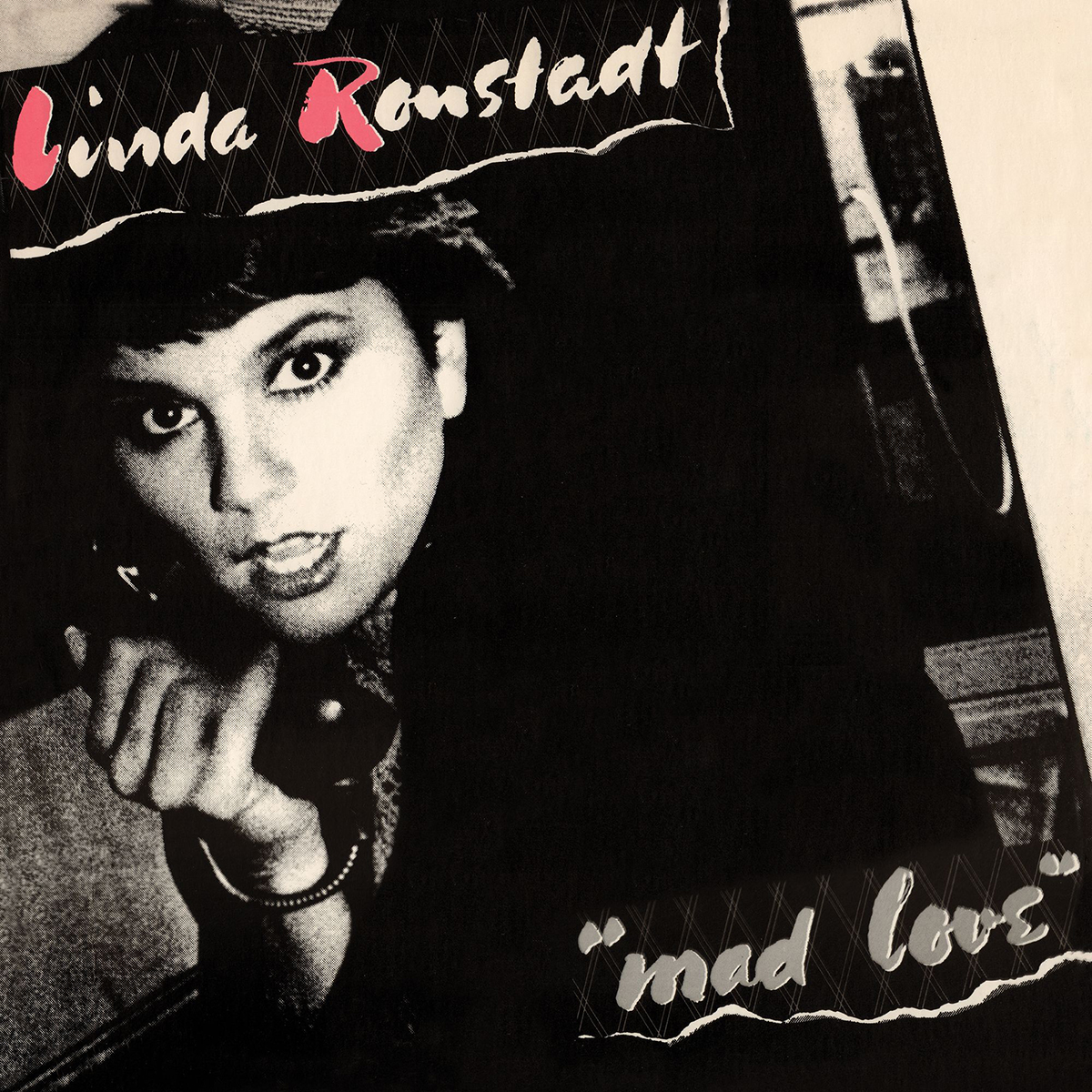

Guitarist Danny Kortchmar has said that 1980’s Mad Love was your best album. Do you agree?

Guitarist Danny Kortchmar has said that 1980’s Mad Love was your best album. Do you agree?

I think my best singing came in the ’90s, but because of Danny’s playing, I was able to really take it up a hitch on that album. He was absolutely seminal in the production of that record. I learned a tremendous amount from him.

You covered three Elvis Costello songs on Mad Love. What about them appealed to you?

The lyrics to “Party Girl” are astounding. “I’m a guilty party and I want my slice but I know you’ve got me and I’m in a griplike vise.” Holy sh*t! It’s a beautifully crafted song—I know a beautifully crafted song when I hear one. So was “Alison.” Those were the songs that were available then. You couldn’t always get a new song from Jackson Browne or J.D. Souther because they were making their own records. I got what I could get from them, but I couldn’t get a whole album’s worth of songs. I had to do with what I could find.

Some critics felt you were jumping on the new wave music bandwagon with Mad Love. Did that bother you?

Yeah, I jumped on it all the way to Gilbert and Sullivan! [Ronstadt performed in a 1980 Broadway production of The Pirates of Penzance.] I never paid any attention to any of that. We learned very early on that you don’t ever read reviews because if you believe the good ones you have to believe the bad ones. You don’t do it for prizes or praise or publicity. You do what you need to do.

Related: Part two of our Linda Ronstadt interview on the Eagles’ start and the SoCal music scene

Watch Linda Ronstadt sing “Blue Bayou” live

Ronstadt’s recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

9 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe greatest set of Female pipes ever. Sure, she took that voice elsewhere – who could blame her – as the rock scene she dominated became a bore for a vocalist that exceptional. Seeing and hearing her live was transformational for teenage boys like me who thought they were so tough. She was all the heartbreak you could ever need. Fine musician surrounded by devoted and talented friends.

Well put!

I agree wholeheartedly!

The most insightful interview of a singer ive ever read. Her own enthusiasm to challenge herself in all the different genres of music she loves is vividly real & shes such a natural and so disarmingly honest person about it all. ..a great interview!

Thanks so much! The link to the second half can be found in part one. And we’ve also just published a two-part interview with Linda’s producer, Peter Asher. Enjoy!

She is a great interview. Pointing out certain lyrics, and who played with her and how she learned from that person really gets the reader some good information. I wish I’d seen her live. So sorry she is no longer able to sing.

Boy, she was a damn good looking woman.

Simply the best pure singer of her generation, and it’s not even close. Saw her in 76 in Houston, and in 77 at the Superdome. She was the biggest female rock star in the world. Always surrounded by legends. Live she was breathtaking. I last saw her with Emmylou at Symphony Hall in Atlanta in 99. A glorious night with another band of legends. There will never be another Linda.

Ronstadt is my favorite vocalist of all musical genres. I discovered her at age 10 and have been a fan for nearly 50 years. I missed seeing her live in the 1970’s but did see her “Mad Love” tour…and it was mesmerizing….I have seen her a total of 6 times live in concert. All my musical heroes are getting old or have passed on and Ronstadt is now 76….her music lives on and on…and that is her gift.