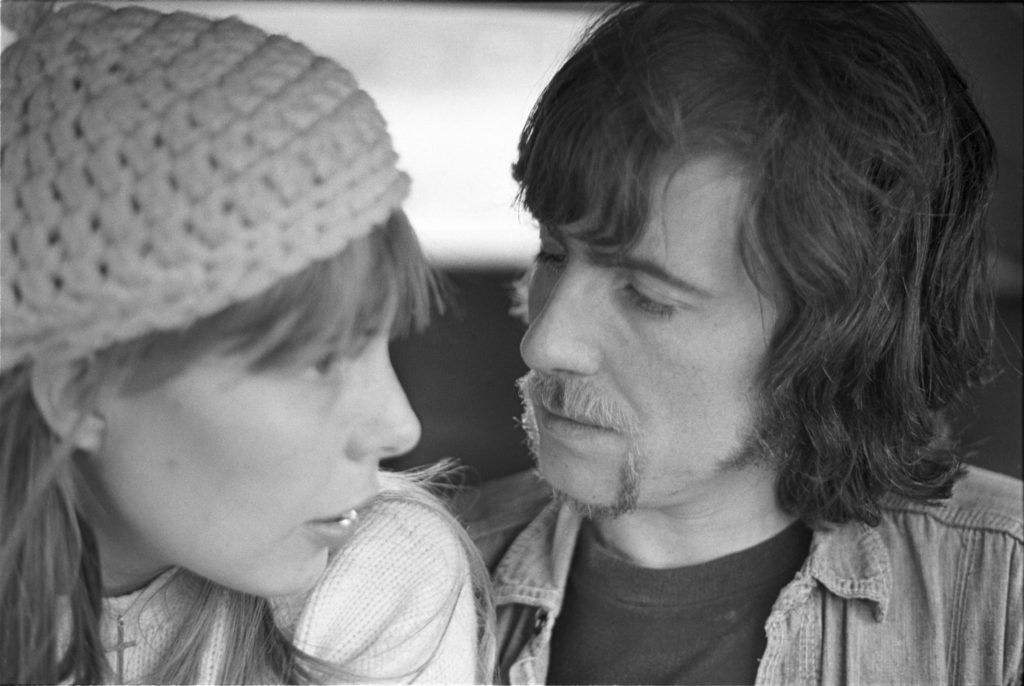

In late 1969, deeply in love with Graham Nash and armed with a batch of songs reflecting her life living with him in Hollywood’s Laurel Canyon, Joni Mitchell was ready to record her third album. Returning to A&M Studios in Hollywood, where she’d crafted the Clouds LP with producer Paul Rothchild, she was full of confidence, determined to control the sessions completely on her own for the first time (David Crosby produced her debut Song to a Seagull in 1968). As a painter as well as musician, she was very aware of the art history model of students attaching themselves to a “master” to learn their craft, but now felt her apprenticeship was over. In an interview with Melody Maker, admitting she was hesitant to collaborate with other musicians, she asked, “How many times do you hear about painters working together?” As her friend and lover James Taylor later said, “Joni not only did the painting, she made the canvas.”

In late 1969, deeply in love with Graham Nash and armed with a batch of songs reflecting her life living with him in Hollywood’s Laurel Canyon, Joni Mitchell was ready to record her third album. Returning to A&M Studios in Hollywood, where she’d crafted the Clouds LP with producer Paul Rothchild, she was full of confidence, determined to control the sessions completely on her own for the first time (David Crosby produced her debut Song to a Seagull in 1968). As a painter as well as musician, she was very aware of the art history model of students attaching themselves to a “master” to learn their craft, but now felt her apprenticeship was over. In an interview with Melody Maker, admitting she was hesitant to collaborate with other musicians, she asked, “How many times do you hear about painters working together?” As her friend and lover James Taylor later said, “Joni not only did the painting, she made the canvas.”

Mitchell had already seen substantial success as a songwriter and performer, beginning with recordings of her early songs by Tom Rush and Judy Collins in 1967, and her signing to Reprise Records the following year. As a singer she had a supple vocal range, perfect pitch and the ability to jump to high notes with a kind of built-in falsetto. Her guitar playing combined typical folk fingerpicking idioms with robust explorations of unusual “dropped” tunings, giving her six-string Martin D-28 the ringing sound of a 12-string. This approach had been necessitated by the damage done to the strength of her left hand by childhood polio—playing a guitar with less string tension was much easier, and she could play a full chord with her right hand alone. (Guitar aficionados say she’s used more than 50 different tunings over the years.)

For her new album, she planned to make more use of the piano as a lead instrument, having incorporated the influence of Chopin, Ravel and Satie. The critic Robert Christgau suggested her reliance on piano represented “a move from the open air to the drawing room,” with a gain in gravitas she could completely back up.

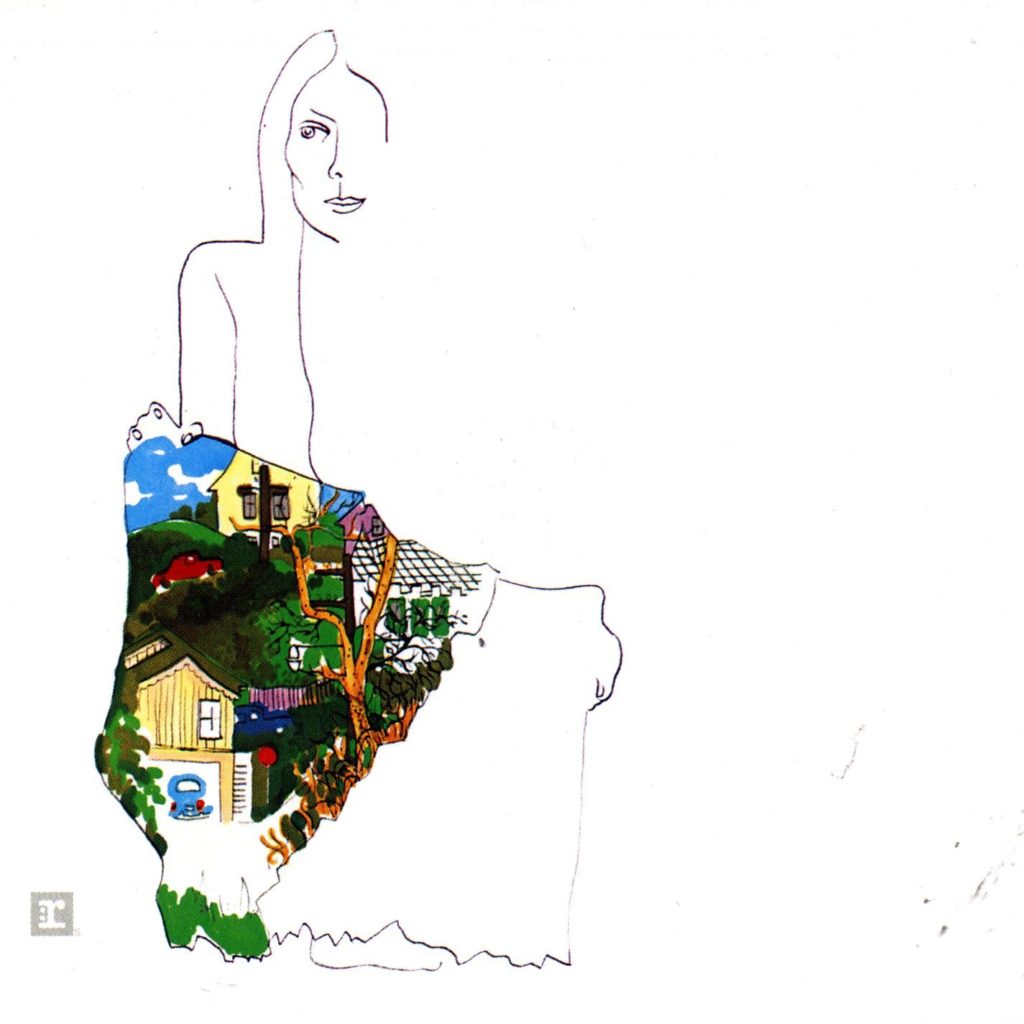

Released in mid-March 1970, Ladies of the Canyon is solid throughout, and sets out clearly the direction Mitchell would take for the rest of her career, leaving behind many of the constraints and limitations of “folk music” for a genre-less art that cannot be pigeonholed as jazz, pop, rock, world music or anything else. Eschewing the standard “produced by” credit, she opted for “composed and arranged by Joni Mitchell,” and painted a cover that’s half black-and-white self-portrait, half colorful Laurel Canyon map.

The album begins with the gentle “Morning Morgantown,” which at first echoes the feel of both “Chelsea Morning” and “Both Sides, Now” in its simple voice/guitar opening. But 45 seconds in, an overdubbed piano enters, playing a kind of music-box counterpoint. The arrangement serves notice that the two lead instruments will share space on the ensuing tracks.

It’s followed by one of Mitchell’s most cerebral and still emotional songs, “For Free,” which was generated by the sound of a Lower Manhattan street musician playing the clarinet “real good, for free.” The excellent opening couplet (“I slept last night in a good hotel/I went shopping today for jewels”) introduces the storytelling frame of the song, and the economic critique to come. As a bonus, the vocal contains the idiosyncratic pronunciation of “jew-ells” and “schoo-ells” that seems playful but is delivered dead straight. Maybe it’s Mitchell’s way of saying, “I know perfectly well how to rhyme, but I may break the rules and plead ‘poetic license’ if I need another syllable or two.” In the lyrics, Mitchell meditates on her ambivalence about showbiz (“I’ll play if you have the money/Or if you’re a friend to me”) and commiserates with her fellow musician (“Nobody stopped to hear him/Though he played so sweet and high/They knew he had never been on their TV/So they passed his music by”). Still, she only empathizes with him so far—she too crosses the street instead of following an instinct to sing with him. A beautifully melancholy clarinet obligato from Paul Horn concludes the track.

“Conversation” contains the first of the album’s stacked, wordless vocal interjections, directly influenced by Mitchell’s admiration for the harmonies of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, which she saw birthed firsthand. It also features Jim Horn on baritone sax and Paul Horn’s flute, the kind of added color Mitchell pursued when she recorded and toured with jazz players like Tom Scott and Jaco Pastorius a few years later. The female narrator of “Conversation” admires the neglected partner of another woman, who “removes him like a ring/To wash her hands/She only brings him out to show her friends.” Admitting “I want to free him,” she soothes him when he comes to her for “comfort and consolation,” unable to end his unhappy primary relationship.

The song might be autobiographical or not—as Mitchell told the writer Jacoba Atlas, “Even if I’m writing about myself, I try to stand back and write about myself as if I were writing about another person…have a conversation with myself. You lay out a case and argue with yourself about it, and with no conclusions.”

There’s no doubt that “Willy” is almost entirely about Graham (middle name William) Nash: when Mitchell performed the song in a medley with “For Free” on The Dick Cavett Show on Aug. 19, 1969, just after the Woodstock Festival (which she declined to attend), she said it was about “my man.” The song only has two verses, each beginning with concise lyrics expressing a puzzling duality: “Willy is my child, he is my father” and “Willy is my joy, he is my sorrow.” Perhaps the problem is Willy doesn’t want to get married (“He cannot hear the chapel’s pealing silver bells”) or is still getting over some emotional trauma (“He says he’d love to live with me/But for an ancient injury”). Mitchell has said that women are raised to fear “the big hurt,” and are taught to be cool and noncommittal around suitors, and “Willy” more than hints at that with “You’re bound to lose/If you let the blues get you scared to feel.”

Watch Mitchell perform “Willy” and “For Free” on The Dick Cavett Show

The album’s title track is a portrait of true-life characters, and the flora and fauna of Laurel Canyon. It’s very detailed and poetic: “Trina wears her wampum beads/She fills her drawing book with line/Sewing lace on widows’ weeds/And filigree on leaf and vine” and “Estrella circus girl/Comes wrapped in songs and gypsy shawls/Songs like tiny hammers hurled/At beveled mirrors in empty halls.” Again, the multi-track Mitchell vocals doing “la-la-la” act like a wordless doo-wop Greek chorus.

“The Arrangement” is another critique of wealth and status, driven by the piano and an especially impassioned vocal. The accusatory opening lyrics are cinematic, pulling back from a closeup to a wide shot: “You could have been more/Than a name on the door/On the thirty-third floor in the air/More than a credit card/Swimming pool in the backyard.” It ends a flawless first side, but some of the album’s biggest successes are still to come.

Side two of the LP starts with “Rainy Night House,” with a fine cello line played by Teressa Adams, “The Priest,” an enigmatic short story with some resonant religious imagery (“He took his contradictions out/And he splashed them on my brow”) and “Blue Boy,” in which a Chopinesque piano part meets a story that might be set in the Renaissance (“Like a pilgrim she travelled/To place her flowers/Before his granite grace”).

Then the big guns come out. “Big Yellow Taxi,” with its humorous ecological advocacy, immediately became an FM radio favorite (Milt Holland’s percussion work helped Mitchell’s guitar gain even more oomph). As a pop single it petered out at #67 on Billboard’s Hot 100, but it did much better when a live version from the Miles of Aisles double-LP was released in 1974. The lyrics “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot” and “Don’t it always seem to go/That you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone” are still quoted often and have become a part of popular culture. The song’s conclusion takes a sharp turn from considering the effects of the chemical fertilizer DDT on apples: “Late last night I heard the screen door slam/And a big yellow taxi took away my old man.” She doesn’t say why he’s leaving, but it’s obviously a surprise. Maybe there’s no solution to the puzzle—Mitchell is simply saying we don’t appreciate the value of the our planet or our personal relationships until we lose them.

“Woodstock,” which was riding high on the pop charts in CSN&Y’s pumped-up version when Ladies of the Canyon came out, follows “Big Yellow Taxi.” Mitchell’s version is a whole ’nother thing. The fact that she didn’t experience the festival firsthand gives her the freedom to imagine the scene in metaphors (“I dreamed I saw the bombers/Riding shotgun in the sky/And they were turning into butterflies”) and write about the symbolic impact of the event, leaving out the actual mud and bad LSD.

Related: The story behind Mitchell’s “Woodstock”

Her choice of electric piano is inspired, as the reverberating notes cushion her terrific singing, with the stack of wordless vocal overdubs making another appearance. Mitchell takes a lot of care with each vocal note—listen to what she does to emphasize the word “smog” in the second verse. “We are stardust/We are golden/And we’ve got to get ourselves/Back to the garden” is one of the gentlest calls to activism in rock history, and every bit as powerful as some of the more explicit protest songs of the era.

The album ends with “The Circle Game,” written in 1966. Perhaps because the Tom Rush version was so ubiquitous on FM radio and in folk music circles, she’d passed it over when recording her first two albums. Having taken the reins in the recording studio, and with the encouragement of her super-supportive manager Elliot Roberts, it seemed time to reassert her optimism about the future: “There’ll be new dreams, maybe better dreams and plenty/Before the last revolving year is through.”

Ladies of the Canyon eventually earned platinum status for sales of a million copies in the U.S., but with the release of Blue the following year—an album often picked as Mitchell’s greatest—its reputation has receded over time, becoming “only a prelude” to greater artistic and commercial successes. But neglecting it is a mistake, even given how much competition it has from other Mitchell albums like Blue, Hejira, Court and Spark, The Hissing of Summer Lawns, etc.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Court and Spark

In ill health in recent years, Mitchell may never produce another studio recording, but re-examinations of her entire song catalog are proliferating, with young singers and songwriters discovering treasures throughout her prolific output. And in 2022, she returned to the stage as a surprise guest of Brandi Carlile’s at the Newport Folk Festival as she joined those paying tribute to her by singing her songs. The live souvenir—and other Mitchell recordings—are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Video: Listen to CSNY’s version of “Woodstock” from Déjà Vu

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe three “ladies of the canyon” were not “invented” at all, but actual real live friends/aquaintances of JM’s. https://jonimitchell.com/music/song.cfm?id=139

I stand corrected! Thanks so much! Will endeavor to change it.

I caught her Miles of Aisles concert and it was one of the finest concerts I remember. My lady, a joint, and Joni Mitchell…Perfect.