As 1968 began, Johnny Cash was an American treasure, and as far as the audience was concerned, he was just about buried. Dismissed by the mainstream that once embraced him, he was relegated to the provincial confines of the country charts, and signed to a label that showed no interest in changing that fact. His personal life was dogged by alcohol, drugs and destructive behavior. In January he descended into Tennessee’s Nickajack Cave intending to commit suicide, but by year’s end his life would turn completely around, including a career revival driven by a now-legendary recording.

As 1968 began, Johnny Cash was an American treasure, and as far as the audience was concerned, he was just about buried. Dismissed by the mainstream that once embraced him, he was relegated to the provincial confines of the country charts, and signed to a label that showed no interest in changing that fact. His personal life was dogged by alcohol, drugs and destructive behavior. In January he descended into Tennessee’s Nickajack Cave intending to commit suicide, but by year’s end his life would turn completely around, including a career revival driven by a now-legendary recording.

A major crossover success in the late 1950s, Cash was simultaneously prolific and ambitious. He released the first LP in Sun Records history, and soon after jumped labels to Columbia (though Sun still possessed many unreleased tracks, which it issued in competition with new material for years to come). His records surveyed country, gospel, rock and more, and touched on societal issues from life in the prison system to the plight of Native Americans, focusing exclusively on the latter on the 1964 collection Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. His strong social advocacy alienated radio programmers and listeners, and contributed to his falloff in popularity. He reached #17 on the Billboard pop singles chart while also topping the country chart with “Ring of Fire” in 1963, and achieved lesser success with 1964’s “Understand Your Man,” another country number one that reached #35 on the pop chart, but those marked the end of his mainstream relevance for several years.

Also problematic were personal issues that had worsened for a decade. There were multiple arrests (including in 1965 in El Paso for carrying more than 1,000 pills across the Mexican border in his guitar case), a string of wrecked cars (not least among them one he borrowed from June Carter), destroyed hotel rooms, failure to appear for scheduled shows and more. Despite his popularity in country music, he was even banished from the Grand Ole Opry following an onstage incident in 1965.

And yet, he kept releasing new music and performing on the road. His 1967 duet with June Carter on “Jackson” would earn him the first of his 18 Grammy awards, and soon after 1968 arrived, he would deliver a seminal live show, at California’s Folsom Prison on January 13.

Performing for prison inmates was nothing new for Cash—he had played about 30 such dates over a decade, including a performance at San Quentin when Merle Haggard was an inmate. He had long aspired to record one of those shows for a live album, but the notion was rejected right along by Columbia brass. Don Law ran the label’s Nashville division, an administration not noted for its artist-friendly environment. When Law was sent into retirement in 1967, the label installed Bob Johnston in the role, a change that opened the door for Cash. Johnston embraced the idea of a prison show recording, and though he claims upper management at the label refused permission to move forward, he shepherded the project to fruition, from recording to release.

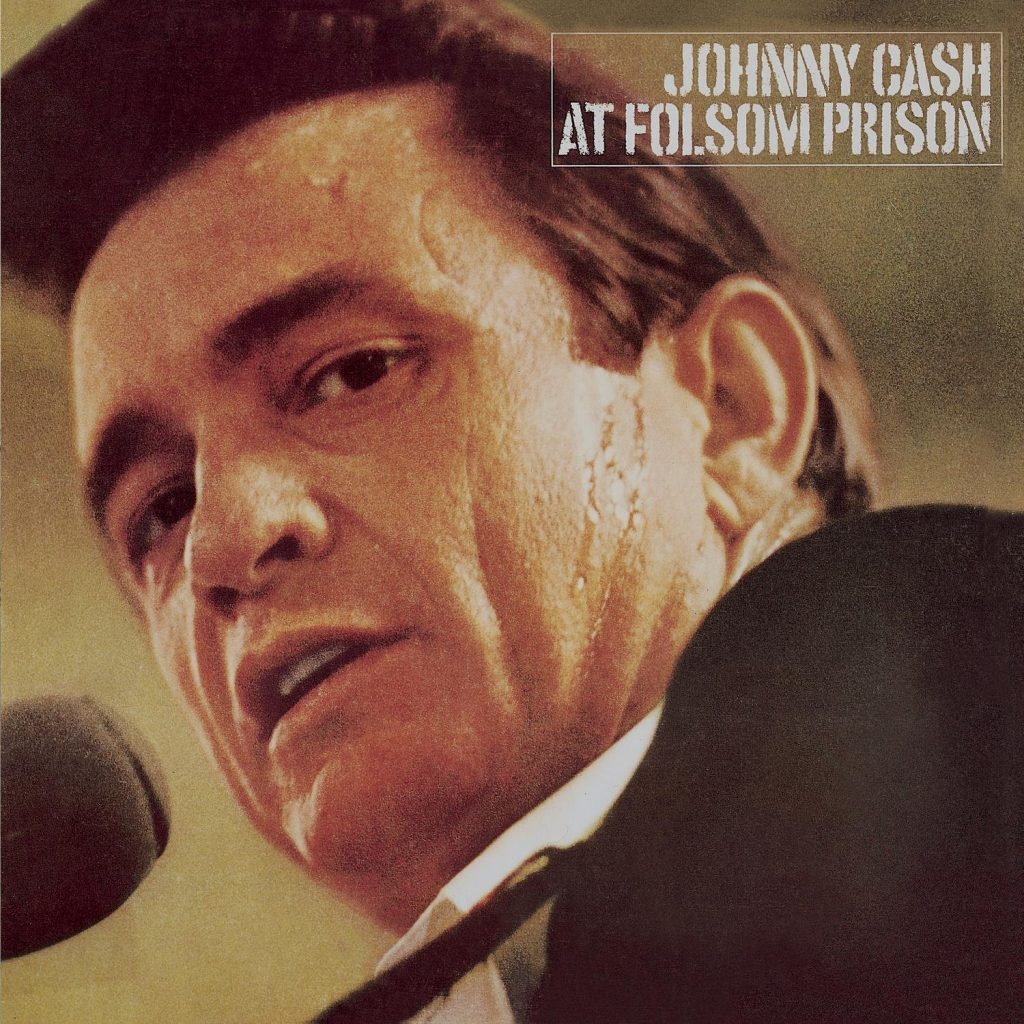

Cash’s instincts about the project could not have been more right. At Folsom Prison is a remarkable record, as compelling for its atmosphere as its artistry. Recorded in a cafeteria using trucks rolled in from San Francisco, the Johnston-produced album features highlights from a pair of shows that day (though all but two of the selected versions are from the first performance), both of which have since been released in full over the course of various retrospective editions.

Related: Our interview with producer Bob Johnston on his work with Cash and Bob Dylan

The album has as many distinctive qualities as songs, driven by the raw personality of Cash’s performance. In a set heavy with grim material, he remains playful and engaged; there is immense charm to the warts-and-all quality of his stumble over audience laughter in the plaintive miner’s story “Dark as a Dungeon,” and his laughing delivery of Shel Silverstein’s bobbing gallows number “25 Minutes to Go” is utterly fearless. Set alongside mundane announcements to inmates from the stage, his presence forges a stark, fascinating dynamic.

Watch an animated video for “25 Minutes to Go”

It’s also a showcase for the propulsive energy of Cash’s band the Tennessee Three, set against the venue’s Spartan confines. W.S. Holland’s drums rattle immaculately alongside Cash’s whistle-stop harmonica in “Orange Blossom Special,” while Luther Perkins (no relation to Carl Perkins, who also guests in the show) edges it with electric guitar twang. Marshall Grant’s bass adds presence to every arrangement, plumping the dark, earnest “Give My Love to Rose,” and supporting the rough-hewn gravity Cash’s vocal brings to another prison number, “I Got Stripes.”

Listen to “Orange Blossom Special” from the album

Two of the record’s most indelible moments have been blurred by later revelations. The album begins with the singer’s traditional opening line of, “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash” to a quiet room, the silence of which enhances its impact. The knowledge that MC Hugh Cherry instructed the 1,000-member audience to remain silent until the show began transforms the moment into simple showmanship, more effective for the recording than the in-show experience. But at least it happened.

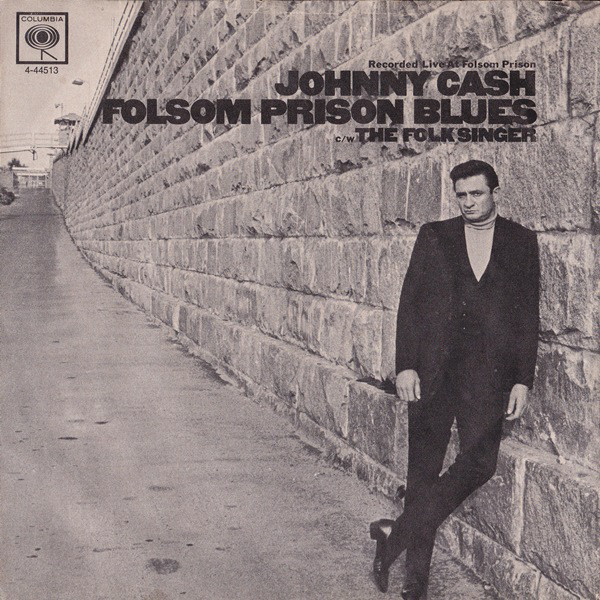

More problematic is a stunning bit in the ensuing take on Cash’s 1955 track “Folsom Prison Blues,” when his delivery of the iconic lyric “I shot a man in Reno/Just to watch him die” elicits a cheer from the audience. Decades later, it was discovered that those cheers were spliced into the recording by Johnston for effect, and the reaction wasn’t real (though Columbia has left it intact in all reissues to preserve artistic intent). Knowledge of that edit makes listening to the song an entirely different experience, particularly given that the notion of convicts specifically cheering such a thorny lyric was a haunting one.

Fortunately, there are plenty of other highlights, not least when Cash is joined by June Carter (less than a month before his onstage proposal to her in Canada) for the springy “Jackson.” Cash’s rugged bass-baritone provides a lively lead, and Carter’s accompaniment soars in its own way when she grabs a verse, leading to vocal interplay that fuses their distinctive charms magically.

The Statler Brothers also join in, appearing as a chorus for a moving finale of “Greystone Chapel,” a composition by Folsom inmate Glen Sherley that the performers learned the night before.

Columbia was as good as its word, offering minimal support for the album’s release that May, but Johnston and others pulled strings to get the album airplay. The lead single “Folsom Prison Blues” was temporarily withdrawn in the wake of Robert Kennedy’s June 5 assassination, and then sent back to radio with the “I shot a man in Reno” line removed. It would reach as high as #32 on the pop singles chart.

At Folsom Prison received strong reviews and word of mouth when it was released on May 6, 1968, and climbed to #13 on the Billboard pop album chart, rejuvenating Cash’s career. He would soon deliver several more albums recorded behind prison walls and, more importantly, would get his drug problems largely under control. Half a century later, the record remains an astonishing landmark, a turning point not only in one of music’s great careers, but in the history of American music. It’s available for order in the U.S. here and the U.K. here.

Listen to “I Got Stripes” from At Folsom Prison

[A new book, The Complete Johnny Cash: Lyrics From a Lifetime of Songwriting, is coming this fall. The title, with Cash as author along with his longtime chronicler, Mark Stielper, arrives October 14, 2025, and is available for pre-order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Related: Our Album Rewind of Cash’s Unchained, recorded with Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationWhen the legend becomes un-facted . . .

At any rate, we’ve learned that many “live recordings” have been “augmented” after the fact. As St. John the Lennon once said: “You bounder! You cheat!!”

Detracts not a whit from a magnificent LP, and career. I don’t think I heard what the bleep in “A Boy Named Sue” covered up until 10 years ago.

Given that an ad in New York’s Village Voice, the country’s “original” alternative newspaper, is what alerted — and helped sell — me on the album at its release, I wonder how “minimal” Columbia’s promotion was. I would bet they placed it in other underground papers as well.

Glen Sherley’s story deserves its own story. Cash was given “Greystone Chapel” the night before the concert, learned it, and apparently surprised the bleep out of Sherley, sitting at the front of the audience. In 1971 Sherley was paroled. He joined the Cash performing entourage, but just couldn’t sustain a life outside prison. He was dismissed, and in 1978 committed suicide.