When you think of “MacArthur Park,” your mind probably settles first on Richard Harris’ dramatic pop rendering, a #2 hit in 1968, or Donna Summer’s disco-ization, which went to #1 in 1978. But did you know that Waylon Jennings, the late country music superstar, cut a version in 1969, which he took to #23 on the Billboard country chart?

When you think of “MacArthur Park,” your mind probably settles first on Richard Harris’ dramatic pop rendering, a #2 hit in 1968, or Donna Summer’s disco-ization, which went to #1 in 1978. But did you know that Waylon Jennings, the late country music superstar, cut a version in 1969, which he took to #23 on the Billboard country chart?

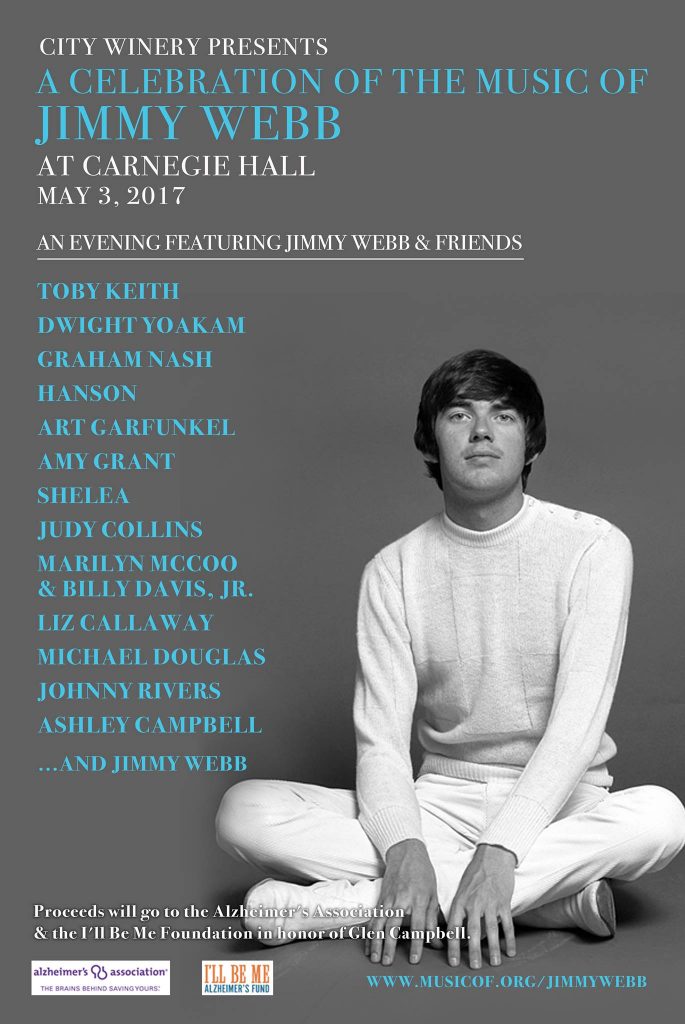

The song has also been covered by everyone from superstar vocalist Tony Bennett to Motown’s Four Tops, from jazz guitarist Larry Carlton to British blues great Long John Baldry. At the May 3, 2017, Carnegie Hall concert called “A Celebration of the Music of Jimmy Webb: The Cake and the Rain,” it was another country star, Toby Keith, who took on the classic tune, and the fact that his version had more of the exaggerated theatricality of Harris’ than with Jennings’ relatively subdued approach, but echoed neither too closely, says plenty about the adaptability of Webb’s music.

Drawing upon the bravado Webb deliberately and unapologetically wrote into it, Keith, in short, nailed it, with Webb himself providing the moving mid-song piano solo. Declaring, as he took center stage, that this performance was about to be “the most challenging of my career,” Keith—without ever losing his Oklahoma twang—alternately soothed and belted the hell out of the tricky tune, built upon changes in tempo and temperament, wowing the New York audience.

Keith’s turn at the mic came toward the end of the 90-minute program. By then we’d already heard Webb’s songs—both the mega-popular ones and some less known—interpreted by a parade of stars and up-and-comers. The three brothers who call themselves Hanson—like both Webb and Keith, fellow Oklahomans—had come out first. Isaac, Taylor and Zac Hanson had ranged in age from 11 to 16 when they had a #1 teen-pop hit in 1997 with “MMMBop.” Now here they were, all grown up and singing a cappella on Webb’s “Oklahoma Nights,” which Webb recorded with Vince Gill in 2010. They were followed swiftly by actor Michael Douglas, who attempted to sum up Webb’s gift in way too short a time slot, making the point that Webb “works with an inner collaborator,” before making way for Judy Collins.

Judy Collins at the Carnegie Hall Jimmy Webb tribute concert (Photo by Al Pereira, used with permission)

At 78, Collins’ voice remains pure and unsullied. She sat at the piano and sang “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” sans other accompaniment. She’d recorded it on her Judith album back in 1975, after both Joe Cocker and Glen Campbell had given it a whirl. Here she emphasized the poetics of Webb’s words—“The moon’s a harsh mistress, the sky is made of stone/The moon’s a harsh mistress, she’s hard to call your own”—and set up a contrast that would be explored by the next set of performers.

Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr. were among the first to establish the name of Jimmy Webb as a formidable craftsman. As the lead vocalists of the 5th Dimension, they cut his “Up—Up and Away” in 1967 and, almost exactly 50 years ago, watched it fly into the top 10. Compared to a song like “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” the sunshiney, multiple-Grammy-winning 5th Dimension hit could nearly be seen as whimsical, and at Carnegie, their voices still soaring, McCoo and Davis, backed by the house band, recreated it flawlessly.

Note: The videos from the concert have been removed from YouTube

Watch Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis sing “Up–Up and Away” at the rehearsal for Celebration of Jimmy Webb

Related: Part 1 of BCB’s interview with Jimmy Webb

Throughout the evening, reminders of Webb’s diversity as a composer were affirmed. More than anything though, what came across was that Jimmy Webb has always written first and foremost for singers capable of conveying depth and emotion. Davis lingered onstage as his partner exited and informed the audience that it was his group that had first recorded Webb’s “Worst That Could Happen” in 1968. Released on their album The Magic Garden that year—an album consisting almost exclusively of Webb compositions—it went nowhere. Then, the song found its way and the Brooklyn Bridge, a singing group led by Johnny Maestro, who’d sung lead with the Crests, of “16 Candles” fame, in the ’50s. Maestro and his new group got hold of “Worst That Could Happen” and took it to #3 but here, it was up to Davis to return the song to its original glory—like Collins, he’s 78 and hasn’t lost a thing.

Watch Davis sing “Worst That Could Happen” at the rehearsal

B.J. Thomas was next. Another Oklahoman, he’s best known for “Hooked On a Feeling,” but at Carnegie he chose “Do What You Gotta Do,” a song recorded in the past by Johnny Rivers, Nina Simone and others. Thomas’ reading was country-flavored, with a touch of soul, and if not one of the evening’s highlights it still provided another way of looking at a Webb tune.

Watch Thomas’ rehearsal performance. (The song title is misidentified on the clip)

Liz Callaway, a singer/actress who is usually heard on Broadway or singing songs for animated films, took on “Still Within the Sound of My Voice,” one of several highlighted tunes closely associated with Glen Campbell.

She was followed by the returning Hanson, applying their impeccable three-part harmony to “Highwayman.” This one has its own notable timeline—recorded first by Webb himself, then Campbell (on his 1979 album Highwayman) and then, six years later, picked up by Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson and Willie Nelson, who cut it for their country supergroup project, also called Highwayman. They liked it so much they adapted the title as the name of their on-and-off group, giving Webb’s song a higher profile than it might otherwise have had.

A young neo-soul singer, Sheléa, who recently toured with Stevie Wonder, began “Shattered,” previously sung by Art Garfunkel on Webb’s own Still Within the Sound of My Voice album, on piano, then moved to the front of the stage to knock it home. After Sheléa, it was time for the heavy names. First was Johnny Rivers, who often called upon Webb’s material during his heyday. Here he was assigned “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” which he recorded on his 1966 Changes album. Rivers didn’t have the hit with it—Campbell, of course did, the following year—but at Carnegie Hall, Rivers, self-accompanied on acoustic guitar, injected it with all of the sense of loss and loneliness of the more familiar Campbell version.

Perhaps Jimmy Webb could have waited till the end of the show to make his grand entrance but he arrived mid-show instead. He described “Galveston,” yet another associated with Campbell, as “the reason I’m sitting up here tonight” and then offered his own take on it. Although he has released numerous albums of his own, Webb has never been known as a singer. But he sure knows how to deliver a Jimmy Webb song convincingly and here he dedicated one of his biggest, “Galveston,” to our men and women in uniform “who made the ultimate sacrifice,” as well as his own father, making one wonder via his strong delivery if perhaps he could have had more success as a performer if he’d chosen that route rather than concentrating primarily on songwriting.

Graham Nash turned out to be the only real disappointment of the show. He sang just great, but was under-utilized, offering only harmonies to Webb’s own version of “If These Walls Could Talk.” Why not let Nash sing a song too? He’s Graham Nash and he’s at your show! Nonetheless, that was it for Nash but the momentum didn’t flag at all. Art Garfunkel took the microphone for “As I Know,” his signature celestial tone admittedly not what it was 50 years ago but still quite touching.

Dwight Yoakam, the first cowboy hat-wearer of the night (he preceded cowboy hat-wearer number two, Keith), was next, bringing some serious country grit to the stage. Following “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and “Galveston,” he explained, Campbell needed “another city song” so Webb wrote “Wichita Lineman” for him. In receipt of a rough sketch of the song, Campbell finished it himself and, needless to say, turned it into a country and pop smash. Yoakam stuck largely to the original arrangement here, albeit stripping the song of some of the sweetness of the Campbell studio recording.

Related: Part 2 of BCB’s interview with Webb

Michael Douglas came back to the stage to elaborate on the Webb-Campbell partnership, his spiel serving as an intro to Ashley Campbell, the youngest daughter of Glen (who was unable to attend due to his worsening Alzheimer’s). Ashley, bearing a banjo, possesses a strong set of pipes, which she applied to “You Might As Well Smile,” which Glen recorded on his 1974 album Reunion—The Songs of Jimmy Webb.

Hollywood giant Catherine Zeta-Jones, who is also Douglas’ wife, proved a formidable vocalist with her “Didn’t We,” which she introduced as a song that “puts the spotlight on Jimmy the poet.” An unannounced special guest, pop vocalist Michael Feinstein, was dazzling, his rich baritone in exquisite form on “Only One Life,” from his own Webb tribute album, dating from 2003. Keith’s “MacArthur Park” followed and then, to wrap things up, the appropriate “Adios,” featuring Webb, on piano, taking the first two verses and then singer Amy Grant taking it from there.

That song was recorded by Linda Ronstadt on her 1989 Cry Like a Rainstorm, Howl Like the Wind album, and also serves as the title track for Glen Campbell’s final studio release, due out in June. Ronstadt, who has Parkinson’s disease, also received a shout-out from Webb from the stage. He did not mention it, but the concert was a benefit the Alzheimer’s Association and the I’ll Be Me Foundation, in Campbell’s honor. He also didn’t mention that he has a brand new memoir, The Cake and the Rain, available here. The focus stayed clearly on the songs this evening, a true celebration of one of the most accomplished and consistently satisfying creators of music for these past five decades.

Webb’s recordings are available here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationClearly a formidable songwriter, right up there I think with Lennon/McCartney. Although I mainly like the stuff Glen Campbell did, he really wrote in a veritable songbook of styles.

Maybe the greatest living songwriter. His songs will last forever. An amazing life indeed. His book “Tunesmith” is about the art of songwriting and it is the gold standard concerning that art form. He is a flat out genius.