Stax Records Founder Jim Stewart, Who Introduced Soul Legends, Dies at 92

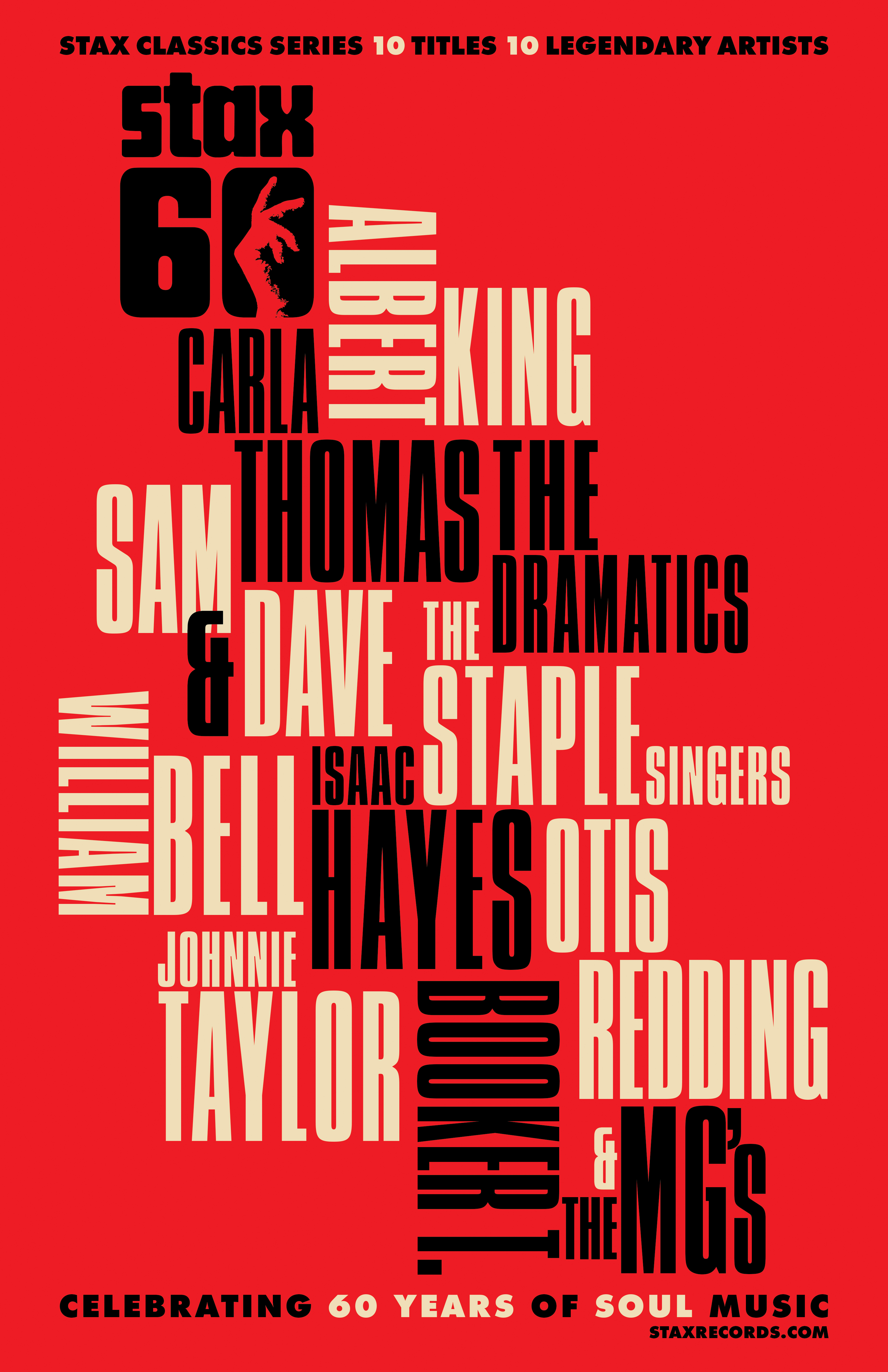

by Best Classic Bands StaffJim Stewart, who founded Stax, the legendary Memphis recording studio and record label that introduced such soul music stars as Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Isaac Hayes and Booker T. & the M.G.’s, died today (Dec. 5, 2022). News of his passing at age 92, while in hospice, was confirmed by noted Stax historian Rob Bowman, author of the book, Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records. The Stax Museum of American Soul Music announced his death, though neither the cause of death nor precise location was known. In recent decades, Stewart kept an extremely low public profile. At his 2002 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, presented by Steve Cropper and Sam Moore, Stewart sent his granddaughter to accept the award on his behalf.

In a 15-year span, Stax is said to have placed 167 singles on the Hot 100, and 243 on the R&B chart.

The label produced such iconic recordings as Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” and “Respect,” Sam and Dave’s “Soul Man” and “Hold On! I’m Comin’,” Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” Booker T. & the MG’s’ “Green Onions,” the Bar-Kays’ “Soul Finger” and Carla Thomas’ “B-A-B-Y,” written by the songwriting team of Isaac Hayes and David Porter, among its hundreds of sides.

Originally known as Satellite, the company was founded in 1957 by Stewart and co-owned with his sister, Estelle Axton, and took its new name in 1961 from the first two letters of their last names. Among the many artists who scored hits on Stax and its Volt subsidiary during the ’60s were Rufus and Carla Thomas, Booker T. & the MG’s (an interracial instrumental quartet that also served as the company’s rhythm section and house band), Johnnie Taylor and Albert King. Redding’s death in 1967 signaled the end of the first Stax era (to which Atlantic Records retains distribution rights).

Subsequently the company spawned a new crop of hit-makers, among them the Staple Singers, and the Dramatics. In 1977, a year-and-a-half after Stax went bankrupt, the company’s masters were purchased by Fantasy, Inc., which revived the Stax, Volt and other subsidiary logos for new recordings, in addition to reissuing older material.

From the Stax Museum website: Inspired by Sam Phillips, a Memphis radio technician who had started producing a few years earlier (and made a huge sum of money on Elvis Presley), Stewart founded Satellite Records. A banker by day and country fiddle player by night, Stewart, born July 29, 1930, knew that he could never make it as professional musician. However, he felt he could be the next best thing–a producer–despite having no experience or knowledge of the recording industry. Satellite cut its first record in October 1957, “Blue Roses,” a country song with low production quality.

From the Stax Museum website: Inspired by Sam Phillips, a Memphis radio technician who had started producing a few years earlier (and made a huge sum of money on Elvis Presley), Stewart founded Satellite Records. A banker by day and country fiddle player by night, Stewart, born July 29, 1930, knew that he could never make it as professional musician. However, he felt he could be the next best thing–a producer–despite having no experience or knowledge of the recording industry. Satellite cut its first record in October 1957, “Blue Roses,” a country song with low production quality.

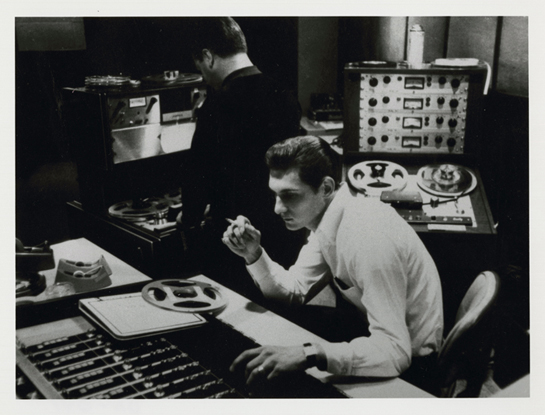

In order to get a better sound, Stewart needed better equipment. He approached his older sister, a music-loving bank clerk, for help and she mortgaged her house to buy an Ampex 350 console recorder for the studio. In 1960, Axton refinanced her house again to fund the studio’s move west from Brunswick, Tenn., to a former movie theater on McLemore Ave. in Memphis. Its conversion into a recording studio was a do-it-yourself project. The cavernous room was partitioned and a control room was created where the screen had been. The floor’s slant helped deaden the sound, a way of trying to control the room’s acoustics on the cheap that would ultimately become a signature part of the Stax sound.

In need of immediate cash flow, Axton turned the theater’s concession stand into the Satellite Record Shop. The shop paid the rent, but it also helped her develop an ear for which records would sell and why.

In need of immediate cash flow, Axton turned the theater’s concession stand into the Satellite Record Shop. The shop paid the rent, but it also helped her develop an ear for which records would sell and why.

Her welcoming nature made the shop a natural hangout. Neighborhood residents would come in, chat with Axton, play records and eventually find their way into the studio. Some groups, like Steve Cropper’s band the Royal Spades, got their foot in the door by knowing Stewart and Axton, while others just walked in, hoping to record.

The new studio’s first single, a duet between Rufus and Carla Thomas called “’Cause I Love You,” became a local hit through radio airplay and the 40,000 copies it sold regionally drew the attention of Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler. The talent exec offered Stax a deal, a contract for a master-lease agreement on all Rufus and Carla discs and handshake deal for first refusal rights on the distribution of all Stax releases. With the deal, Atlantic took over Stax’s distribution, making it easier for the label to get its records into stores. Stewart, however, didn’t read the entire contract before he signed it.

Stax had plenty of records to distribute in the early 1960s. The new studio had cut records by Carla Thomas, the Mar-Keys, Booker T. and The MG’s, Rufus Thomas, William Bell and Redding. The label also released songs by Sam and Dave, who were “on loan” to the studio as part of the deal with Atlantic Records.

The day after Stewart passed, Cropper paid tribute. “The industry lost a major icon yesterday when we lost Jim Stewart. I lost a great friend and had much success with him and STAX.

“Jim had a great trick in finding hit songs,” he continued. “Basically he never liked anything, but if the writer fought for it, he pretty much knew he had a hit. Songs like ‘Last Night’ (The Mar-Keys), ‘Walking the Dog’ (Rufus Thomas), In The Midnight Hour’ (Wilson Pickett), ‘Knock on Wood’ (Eddie Floyd). All of these and more sold over a million copies.

“Jim Stewart taught me so much about the record business. What I didn’t know at the time was, that Jim and I were both flying by the seat of our pants but he was so much older than [me]. Jim always looked up to two people, Sam Phillips and Jerry Wexler.

“The good news for me was that he trusted me with the company and the STAX Artists. We both knew at the same time we had a hit artist with Otis Redding.

“At one time we had 17 artists on the STAX/VOLT labels. A lot to worry about but, not near as bad as Clive Davis and Columbia Records.”

Several days later, Booker T. Jones wrote a guest column for Billboard. “The ship has lost its captain, and our hearts are lost at sea,” he wrote. “As eternal as he seemed to a young boy like me, I thought this day would never come as he pulled me into his dream of making music for the world.”

The label’s success during the decade was in close parallel with civil unrest in the ’60s and the rise in civil rights. Redding’s appearance at 1967’s Monterey International Pop Festival introduced a rising star and became one of legend. He died six months later in a plane crash.

Atlantic was sold to Warner Bros.-Seven Arts in 1967. Stewart made several attempts to negotiate a new distribution deal after the sale, first to join Atlantic in its buyout and then directly with Warner Bros. When neither offer was to his liking, Stax asked Warner for its master tapes back. Warner refused, citing a clause in Stax’s original contract that gave Atlantic “all right, title and interest, including any rights of reproduction, in all Stax’s Atlantic-distributed recordings between 1960 and 1967. Warner also took control of Sam and Dave, who had been “on loan” to Stax as part of their original deal with Atlantic.

When Stewart chose not to renew the deal, he essentially had to start over. The label’s first major hit after severing ties with Atlantic was Johnnie Taylor’s 1968 single, “Who’s Making Love.” Hayes became the label’s biggest star, led by the soundtrack to the 1971 film, Shaft. One year later, Stewart sold his interest in the company.

The original Stax recording studio was torn down in 1989 after years of neglect. The not-for-profit Stax Museum of American Soul Music was opened on the original site in 2003. Estelle Axton died Feb. 24, 2004, at age 85.

Related: Musicians that we’ve lost in 2022

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationSorry to hear this. He was a visionary. He brought the sound of soul to so many who might not of heard it otherwise and helped unite whites n blacks in the power of music. God’s gift to man, make music not war.