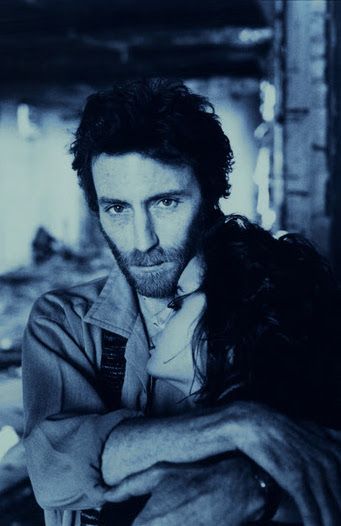

JD Souther: A Vintage Interview with the Gifted Singer-Songwriter

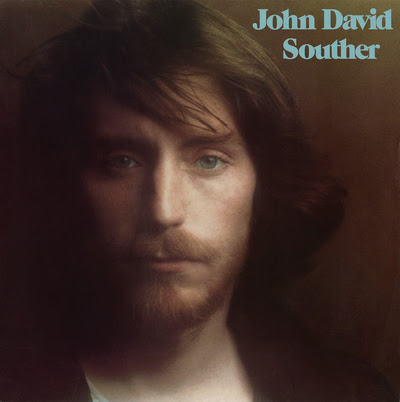

by Jeff Tamarkin The death, at age 78, of JD Souther on Sept. 17, 2024, robbed the music world of a great performer and, especially, a gifted songwriter. Souther—the JD was for John David—was best known for the hit songs he wrote or co-wrote for Eagles (“Best of My Love,” “New Kid in Town,” “Heartache Tonight”), Linda Ronstadt (“Prisoner in Disguise,” “Faithless Love”), James Taylor (“Her Town Too”) and many others.

The death, at age 78, of JD Souther on Sept. 17, 2024, robbed the music world of a great performer and, especially, a gifted songwriter. Souther—the JD was for John David—was best known for the hit songs he wrote or co-wrote for Eagles (“Best of My Love,” “New Kid in Town,” “Heartache Tonight”), Linda Ronstadt (“Prisoner in Disguise,” “Faithless Love”), James Taylor (“Her Town Too”) and many others.

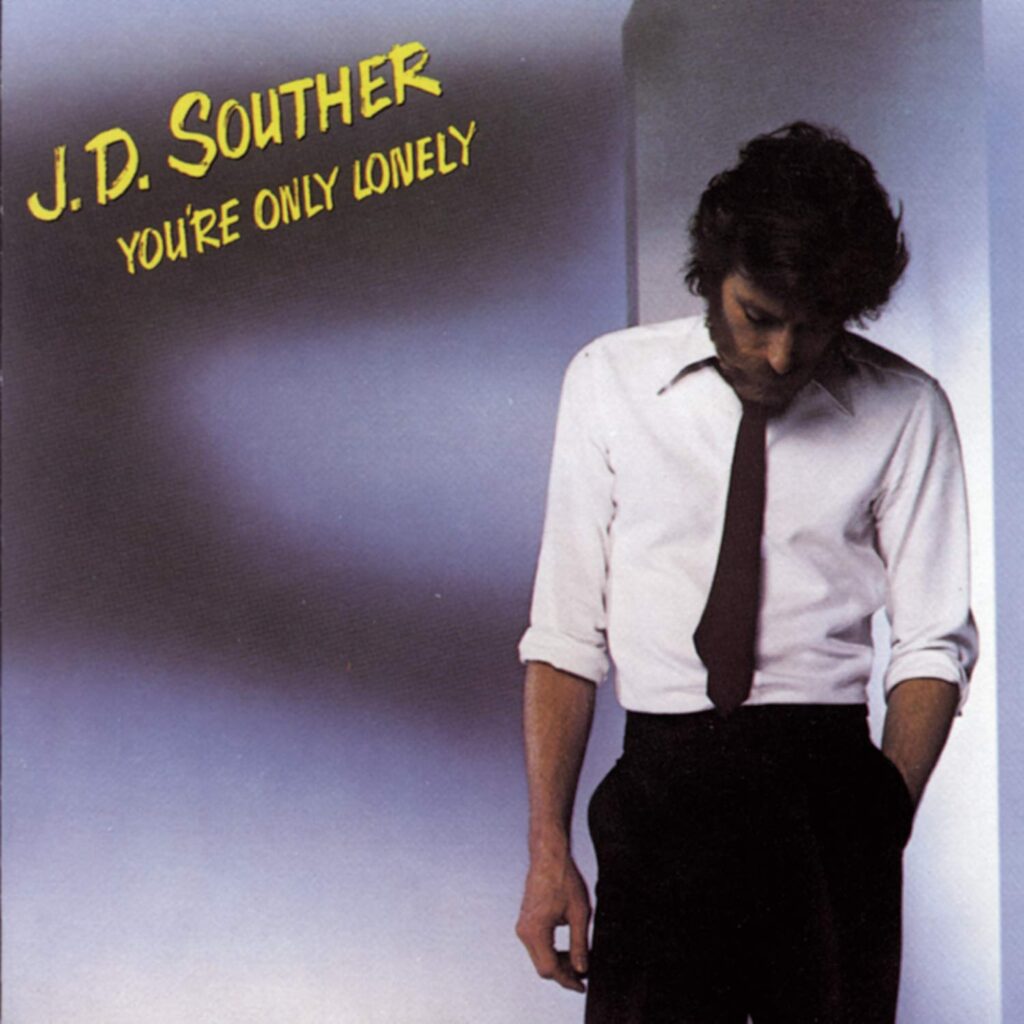

But Souther, born Nov. 2, 1945, also enjoyed appreciable recognition as a solo artist, scoring a Top 10 single with “You’re Only Lonely” in 1979. Although his albums did not burn up the charts, they too had a solid following and contained some of his most underrated music.

In 2015, while Souther was promoting his new album titled Tenderness, Best Classic Bands editor Jeff Tamarkin caught up with Souther and conducted a career-spanning interview with the artist, most of which has never before been published.

Best Classic Bands: You were born in Detroit and moved to Texas for several years when you were a child, before relocating to Southern California. You’ve said that you became a fan of country music when you lived in Texas. Any specific artists?

JD Souther: Well, my parents played country music. My dad was a big band singer, his mother was an opera singer. My mother didn’t like hillbilly music so the only country music I heard was on my own, which came through the country-rock guys I heard when I was in elementary school: Buddy Holly, Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison.

Does this music show up in your early stuff?

Sure; listen to the chord changes. Listen to the voicings and where the melodies go. It’s there. But once I moved to California, I met Linda [Ronstadt], and she turned me on to all this country music and it was fascinating, because back in those days, country music was actually good. It was this primitive art form and there was a lot to learn from it. There was a lot of heart in it, and it was original. It was its own thing in the universe. And it was fascinating to see all of us hippies following along in Rick Nelson’s footsteps, and later Gram Parsons. By the way, Rick Nelson had the first country-rock hit. It wasn’t Poco and it wasn’t the [Flying] Burrito Brothers. He was doing country-rock records when I was still in high school. The long-haired, pot-smoking friends of mine were playing country music.

You weren’t though, not at first.

No, but I was not getting much work as a drummer, which is what I was doing when I moved to California. I’d never even held a guitar. I grew up as a jazz drummer and sax player. I just wasn’t getting any work and someone left an acoustic guitar in my apartment and I started noodling on it. Then I met Glenn Frey [later of Eagles] and we started noodling some more and listening to [folk singer] Tim Hardin and John Sebastian and Bob Dylan and the country guys—we played Hank Williams until all the neighbors were sick of it. Tim Hardin and John Sebastian had a huge influence on me, but they get overlooked. They have oddly unrepresented careers in the pantheon of American songwriters.

Tim Hardin was a tragic character who died young due to drugs.

My first gig on the road in my life, I opened for him—six nights: 11 [of Hardin’s shows] were wretched and one was the best show I’ve ever seen in my life. He was so high by then. He was a complete victim of his habit at that point. It wasn’t a pleasant week but one night he played a set that was magic. People were almost afraid to applaud. You could hear a pin drop.

You’ve also mentioned Cole Porter and the Gershwins as influences.

I don’t have any genre. I agree with Duke Ellington; there’s only two kinds of music, good and bad.

When did you give up the drums and switch to writing the kind of country-influenced folk-rock that attracted people like Eagles and Linda?

I was still playing drums in a band that Norman Greenbaum [of “Spirit in the Sky” fame] and I had. I played drums in the Icehouse Blues Band for a while. I played drums on a lot of my own records. I never gave it up. When I started playing guitar, I was influenced a lot by Tim Hardin because he was playing simple guitar, but he was singing jazz. I love the fact that he was always back of the beat. He had this mellow, unhurried approach to melody that would work with pretty simple guitar changes. Same with John Sebastian—I’m always shocked that more people don’t mention him as a great songwriter. [The Lovin’ Spoonful’s] “Jug Band Music” is a fantastic jumble of great lyrics. It ranks right up there with Chuck Berry and that kind of staccato…making every one of them count.

Did the British Invasion affect you at all?

Oh, sure. The Beatles suddenly made it worthwhile—not just singles but a great album. I remember taking home Rubber Soul and going, “Wow, there’s not a turkey on this.”

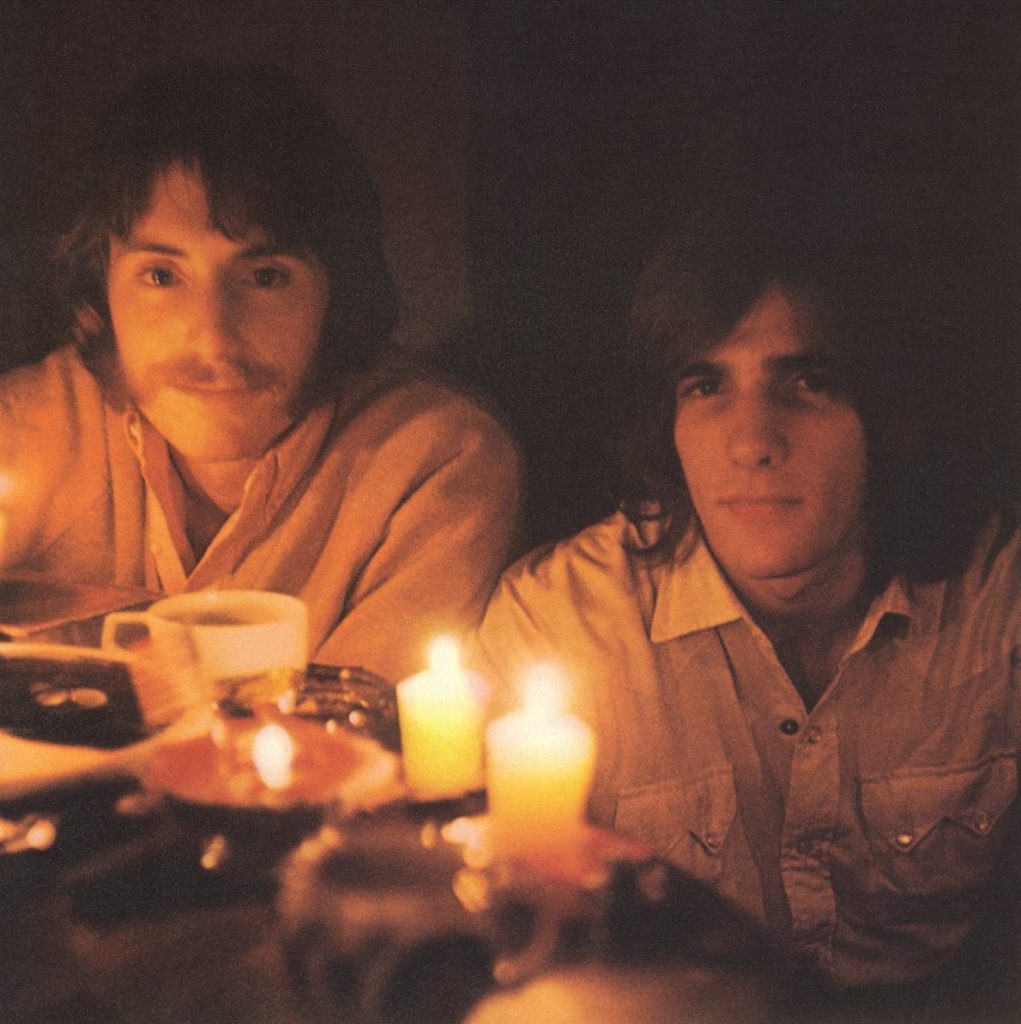

How did you and Glenn Frey come to form the duo Longbranch Pennywhistle?

We started banging around a bit as a duo and we were doing OK. We had a record deal with one of [producer/entrepreneur] Jimmy Bowen’s companies [Amos Records]. We made a record for them with great players. They didn’t know what the hell was going on, so they said, “Who do you want?” and we said, “We want Ry Cooder, we want Doug Kershaw, Joe Osborn, Jim Gordon, James Burton, Larry Knechtel.” And we weren’t very good songwriters then—only two or three of those songs are any good but we had a piece of the action. We knew how to do it. We knew those guys and had their phone numbers and knew how to play with those guys and then the second album we were gonna make, we were gonna do with David Briggs—not Nashville David Briggs; the David Briggs who produced Everybody Knows This is Nowhere for Neil [Young]. Neil was a big fan of mine and when the management company split up, Geffen went off to run Asylum Records. Irving Azoff took Eagles, Joe Walsh and Dan Fogelberg, and Elliot Roberts took Joni [Mitchell], Neil and me. I said, “Why me?” He said, “That was Neil’s doing.” Neil said, “This guy Souther, he’s a rare bird.” So, Elliot was my manager then and he wanted me to make a solo album. I was already with Linda and Glenn wanted more people in the band and I wanted to play by myself. I liked what Jackson [Browne] was doing. So off I went on the road with a suitcase in one hand and a guitar case in the other. We were kind of stuck there [with the label] and they wouldn’t let us out of the deal and Jackson and I became friends. Jackson took me to David Geffen’s house, and I played a couple of songs for David. I was so cantankerous I literally played the two most un-commercial songs I had. I’d been fed up with these guys trying to ram commerciality at this other record company and David just said, “OK, great, go make a record.” It was that simple. So, we put some money in a bank account and Jackson and I got little bungalows across the court from each other and I listened to him write and he listened to me write and it was an amazing period of time. I’d go over there sometimes, and Laura Nyro would be there, and he’d come over to my house and Linda would be there. One time the Eagles needed a place to rehearse, and so Linda and I went to the movies.

Listen to “Mister, Mister” by Longbranch Pennywhistle

Related: Our Album Rewind of Longbranch Pennywhistle

Why did you change from being billed as John David to JD?

I didn’t. People started calling me that and it just stuck.

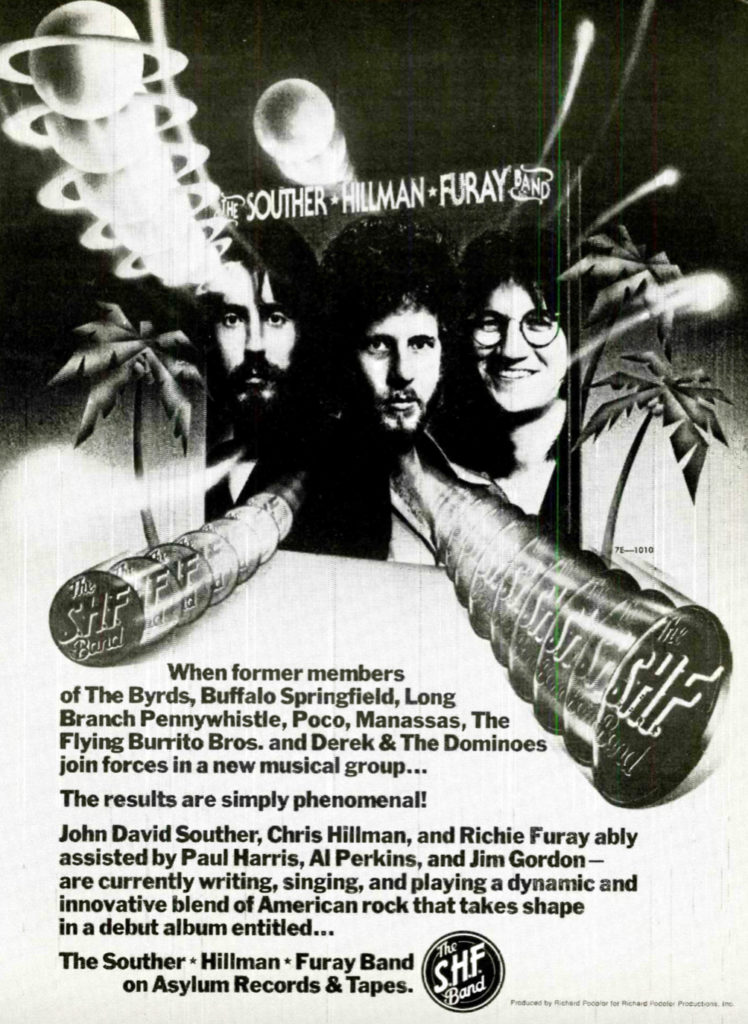

I’ve heard you don’t have great recollections of the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band [with Richie Furay and Chris Hillman]. Is that true?

Not really. I just say that to be funny sometimes. We were just thrown together too quickly. It didn’t evolve organically the way CSN did. It was really David Geffen’s idea to make me famous in a hurry. He came to me and said, “Listen, I’ve got Richie Furay from the [Buffalo] Springfield. I’ve got Chris Hillman from the Byrds. We’ll call it by your names.” I said, “Really, a band? I just got out of a band. I don’t want to be in a band.” He said, “Well, what do you want?” I said, “I want to stand in the middle and I want my name to come first.” He said, “OK, you’ve got it.” We actually worked hard at being a good band. It was just so fast. We were rehearsing in Colorado at Richie’s house. We had people from Rolling Stone coming to our rehearsals. Joni was coming. It was too much pressure. We never really got the chance to get to know each other. Also, two of the guys in the band, Richie and Al [Perkins], were becoming very religious at the time, and the rest of us weren’t. There was friction there, and then right before the second album, Jim Gordon quit. He demanded a piece of the album and his picture on the front. The first SHF album, what’s on the inside now was designed to be on the outside. Geffen said no.

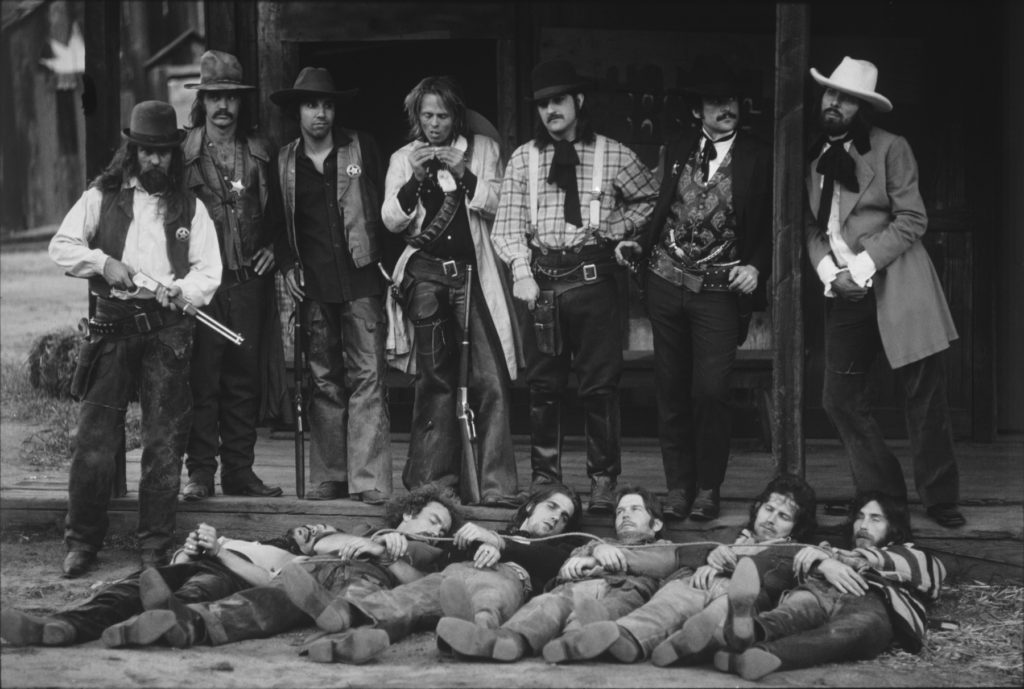

The back cover of Eagles’ Desperado album, shot in Dec. 1972. On the ground (L-R): Jackson Browne, Bernie Leadon, Glenn Frey, Randy Meisner, Don Henley, JD Souther (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

How did things change for you once Linda and the Eagles and so many other people started recording your songs?

Linda made me a professional songwriter. As much as I love Don [Henley] and Glenn and Jackson and [Warren] Zevon, and as good as those collaborations were, I have to say that Linda’s approval and encouragement—she cut 10 songs of mine—really made me a professional songwriter. I trusted her and I still think she has just about the best ear in the business. She took the best songs of mine, the best songs of Zevon, the best songs of Lowell George, the best songs of the McGarrigles. She just had an absolutely unerring ear for music.

Do you have a favorite of the ones she covered?

Not really, although for a long time we thought “Prisoner in Disguise” was the best thing we’d ever done.

She mentioned “Simple Man, Simple Dream” when I talked to her.

She loves that song. I like it too, but I like it for another reason: I like it ’cause it’s short. It’s concise. I did what I wanted to do in two minutes.

Linda told me that she almost wished you weren’t so good at your own songs because when you put them on your own albums, she didn’t get them anymore.

Linda told me that she almost wished you weren’t so good at your own songs because when you put them on your own albums, she didn’t get them anymore.

[laughs] To be more accurate about it, a little bit after that time, she started talking about doing standards. When we were together, we listened to Sinatra records over and over. She said, “I want to do an album with Nelson Riddle and Nelson’s orchestrations of these songs.” But the record company at the time was, “Oh, no,” but I was saying, “Do it, Linda. This is what you love.” If you’re smart and you really have a good musical vocabulary, which she does, you go with what you know.

She feels she didn’t really learn to sing properly until those Nelson Riddle recordings and some of her later albums.

I feel the same way. If the World Was You [2008] was a very precise, experimental thing. I went into that thinking, I want to put together a jazz quintet. It turned out to be a sextet because I met [flutist/saxophonist] Jeff Coffin. But I wanted to be a bandleader of this kind of band. My vocals are important, the songs are important, the words are important, but I’m willing to go some places vocally, to stretch in some ways vocally, to make this thing work. That was a rehearsed album. We played gigs for a month. When we played live, that was a completely different thing.

Listen to Souther and Ronstadt sing “Hearts Against the Wind” from the Urban Cowboy soundtrack

What about the songs that the Eagles did? Any favorites?

They did a great job with everything. Best four-part harmony band ever, as far as I’m concerned. I don’t think they ever did any of my songs a disservice, and I think all of the stuff we wrote together was better because we wrote it together. That was the collaboration of a lifetime for me: first with Jackson, and then after he stopped collaborating with us, still Henley and Frey and I. Then later on, Henley and I and then Henley, Kooch [Danny Kortchmar] and I. That was a great collaborative period of my life. I loved writing with those guys. We were so supportive and competitive at the same time, and I feel certain that we made each other better songwriters. I know that they made me a better songwriter.

Watch Souther sing “New Kid in Town” with One Flew South

You also collaborated with Roy Orbison.

I wrote two songs with him. I actually wrote three, but he cut two.

You also wrote a song that Brian Wilson recorded, “Where Has Love Been?”

It was a lot of fun. I thought he was such a great guy, and I was so delighted to find that he was not this eccentric special needs person that people described him as to me. He’s a great guy; we mostly watched Dodgers games together.

What’s the story behind the song “Her Town Too,” which you co-wrote with James Taylor and Waddy Wachtel?

James and Waddy Wachtel and I were lounging around my house one night imbibing, and Waddy seized the moment and said, “Hey, why don’t we write a song?” James and I both looked at him and said, “What are you, f**king crazy? We’re not working.” Waddy threw a topic out there and James sang the first two lines, I sang the second two and we just kept singing it back and forth. Waddy played guitar and James and I sang that story back and forth to each other until it was done.

Why do you think “You’re Only Lonely” became your biggest solo hit?

It was just a really accessible song, an honest, easy to remember song. It’s a good record. I had a lot of help from my friends. Waddy and Kenny Edwards and Rick Marotta played on it. Henley and Frey coached me on the vocal. The harmonies were beautiful: Jorge Calderon, Peter Asher, Don maybe. [It came out] in 1979, but I wrote it in ’73. It didn’t seem finished. We were working on that album [also titled You’re So Lonely]; I think the working title was White Rhythm and Blues, which would have gone over real well with the record company [laughs], and Waddy said, “Don’t you have any fast songs?” I said no and he said, “Well, anything a little more uptempo, like a single?” I said, “I’ve got this thing I wrote in Colorado in ’73. But it doesn’t have a chorus, it doesn’t have a bridge, and it doesn’t have a last verse.” I sang it for him, and he smacked his head and said, “Sing the first verse again!” So, I did and you know what happened.

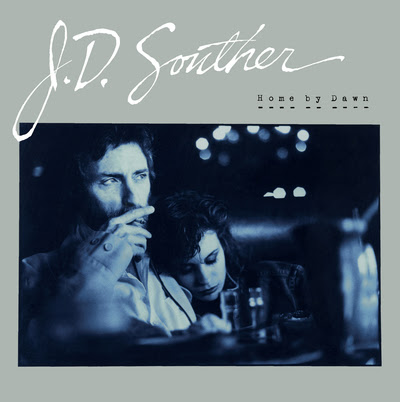

After 1984’s Home by Dawn album, you didn’t make another album for 24 years. What were you doing all that time?

After 1984’s Home by Dawn album, you didn’t make another album for 24 years. What were you doing all that time?

I built a fabulous house that I always wanted to build. I went to New Zealand and skied. I drove around the Midwest and spent a lot of time in Northern California on a friend’s ranch. Took some wilderness trips into the mountains. I just removed myself from the pressure. I did not like MTV and what it did to music, and I didn’t like all that digital slap echo stuff that still makes my skin crawl when I hear it. It just seemed like a good time for me to be out of the picture. Also, to be honest, the men in my family all worked until they were 80 or 90 and by the time they retired they didn’t have much gas left. I had some money, and I built this fabulous house and said, “I’m gonna take a decade off and enjoy myself.”

Why did you decide to come back in 2008 with If the World Was You?

I’m a musician. I had to play. I had to write. I’m a lifer, man. I started playing violin in the fourth grade. My grandma taught me “Nessun Dorma” from [the opera] Turandot when I was four. I never had a plan B. That’s all I’ve ever done. So, to just stop at some place along the road, whether it was popular or not, and keep doing that over and over, is just antithetical to who I am. If I had made more money, I wouldn’t have been any good at it; it wouldn’t have worked.

You did the Natural History album in 2011, where you cut some of the songs you wrote that were big hits for others. Was it just time to take stock of your own work and reassess it?

It was a suggestion by Fred Mollin, the producer, and Chuck Mitchell, the head of eOne Records. He said, “You have all these great songs and the artists that recorded them are all over the map.” He came to see me play in New York and said, “Why don’t you do them the way you’re doing them on stage? They’ve evolved and you have your own style and presentation of these songs. Why don’t you just make a record of those?” So, I did.

You were recently inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. What does that mean to you?

Let’s put it this way: I would give back all the other awards and fight to the death to keep that one. To stand on stage and look out and see Burt Bacharach and Hal David, OK, I guess I got what I wanted. When I first started writing, obviously we all want to write hits because it pays for your life and people get to hear your music, but the main thing for me was to make ’em laugh. And I’ll be goddamned, it happened.

Anything you want to add?

I’ve got the best job in the world. I get to do something that I love more than anything else and that’s difficult for me and continually forces me out of my comfort zone and into a new one. And I get paid for it.

Many of Souther’s recordings are available here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSo extremely sad to hear , I’m heartbroken . I was privileged to see him live in a little bar , very intimate venue , only a 100 or so people in Chicago’s Wrigleville area a while back, was seated in the front row on a folding chair in 2008, and was able to meet / talk with him afterwards , truly was one of the amazing talented , singer, songwriters of our time . He was Elected into the singer songwriters Hall of Fame in 2013 , and performed live on stage with the EAGLES this past January on their Long Goodbye tour

He released his biggest solo album , Your Only Lonely back in 1979 and it was A #1 Adult Contemporary hit for 5 weeks, Souther told interviewers that Roy Orbison, who had a hit with “Only The Lonely,” was a big influence on this song. Said Souther: “I was a little kid when I first heard Roy Orbison, but he was magic. He’s the guy that you turned out the lights and listened to his records by yourself – or with a girl – because he was just completely other-worldly. He had sarcastic and adventurous songs and great arrangements, and then that beautiful, almost operatic voice. Beautiful, natural deep echo on it. He is one of half a dozen or so rockabilly musicians that I really loved. When I was in junior high school was the first time I really started listening to that.

But then I started playing drums all the time, and I got so fascinated with jazz, I didn’t really think much about singing or making rock and roll records for quite a few years. The first song I ever heard called ‘Only the Lonely’ was this song that Frank Sinatra sang. It’s a Johnny Mercer song; it’s on a Sinatra album called Songs for Only the Lonely. There are a lot of songs with that name. But the beat that I used for ‘You’re Only Lonely’ is that rockabilly beat. That sort of break in it was taken from another Roy Orbison record called ‘I’m Hurtin” that I really love.”

He later performed with Roy Orbison’s , On a Black and White Night live the backing band was the TCB Band, which accompanied Elvis Presley from 1969 until his death in 1977: Glen Hardin on piano, James Burton on lead guitar, Jerry Scheff on bass, and Ronnie Tutt on drums. Others involved were Male background vocalists, some of whom also joined in on guitar and keyboards, included Bruce Springsteen, Tom Waits, Elvis Costello, Jackson Browne, Steven Soles, and of course JD Souther. The female background vocalists were k.d. lang, Jennifer Warnes, and Bonnie Raitt.

He was also a principal architect of the Southern California sound and a major influence on a generation of songwriters, JD Souther has either written or co-written some of the Eagles’ biggest hits, including “Heartache Tonight,” “Victim of Love,” “New Kid in Town,” and “Best of My Love,” Don Henley’s super hit “The Heart of the Matter,” and the Eagles’ single from 2007, “How Long.”

He has also written ten songs recorded by Linda Ronstadt, including classics “Faithless Love,” “Simple Man, Simple Dream,” and “Prisoner in Disguise.” He has collaborated with other world-renowned musicians, including his duet “Her Town Too” with James Taylor, and has worked with numerous other artists and writers, including Bonnie Raitt, Warren Zevon, Paul Williams, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Hugh Masekela, Burt Bacharach, Dixie Chicks, Raul Malo, India Arie, Roy Orbison, Arthur Hamilton, George Strait, Brian Wilson, Bob Dipiero, Bernadette Peters, and Trisha Yearwood.

Souther released successful solo albums praised by publications like Rolling Stone, Time Magazine, Jazz Times, and American Songwriter. Mr. Souther’s songs have appeared on over 117 million albums sold worldwide. In 2012, he was cast as a guest star on ABC’s hit show Nashville as legendary producer, songwriter and mentor Watty White.

Mr. Souther has received many accolades including Grammy nominations, Academy of Country Music and American Music Awards, over twenty ASCAP performance awards and the prestigious ASCAP Golden Note Award in 2009.

The world is a little lonelier place without you

Rest in Peace J.D. you will be missed

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1055471475979744&id=100045507043226

“You’re Only Lonely” is the best Roy Orbison song not written or sung by him-too bad he never covered it or did a duet with J. D.

Great interview. Ironically, JD did not live into his 90s like other males in his family. 78 is too young.