Greenwich Village in the ’60s, With Sebastian, Muldaur, Melanie: 2018 Concert Review

by Jeff Tamarkin

Stars of Music + Revolution: Greenwich Village in the ’60s (clockwise from upper left): Jesse Colin Young, Melanie, John Sebastian, David Amram, Happy Traum, Jose Feliciano, Maria Muldaur

They were all celebrating a moment, one with its spiritual and geographic center a few miles and a whole lot of years south: Greenwich Village in the 1960s. They were honoring Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs, Richard and Mimi Fariña and Tim Hardin and Eric Andersen, the Spoonful and the Velvets, men and women who changed lives with a song.

Some of them sang their own tunes, others borrowed. Those who were there, who graced the stages of the Night Owl Café and the Bitter End, the Gaslight and Gerde’s Folk City—a couple of those long-ago places still standing, most now turned into sushi joints or juice bars—would’ve been slotted into little boxes, folk if an acoustic guitar dangled from their necks, folk-rock if they plugged into an amp. No one had yet thought to call them singer-songwriters. The songs they sang—“I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” “Masters of War,” “Femme Fatale,” “Ramblin’ Boy”—defined an era, a time when words mattered and guitars were escaping music stores by the thousands. For a few hours on August 12, 2018, at SummerStage in Central Park, it all came alive again.

Watch John Sebastian open the show

The program, Music + Revolution: Greenwich Village in the 1960s, was organized and hosted by Richard Barone, the former frontman of the Bongos, a band that found its footing across the Hudson in Hoboken, N.J., in the 1980s. Barone released an album in 2016, Sorrows & Promises: Greenwich Village in the 1960s, that started his ongoing tribute. He’s put together other performances in other places furthering the concept, but this night promised something definitive. It delivered.

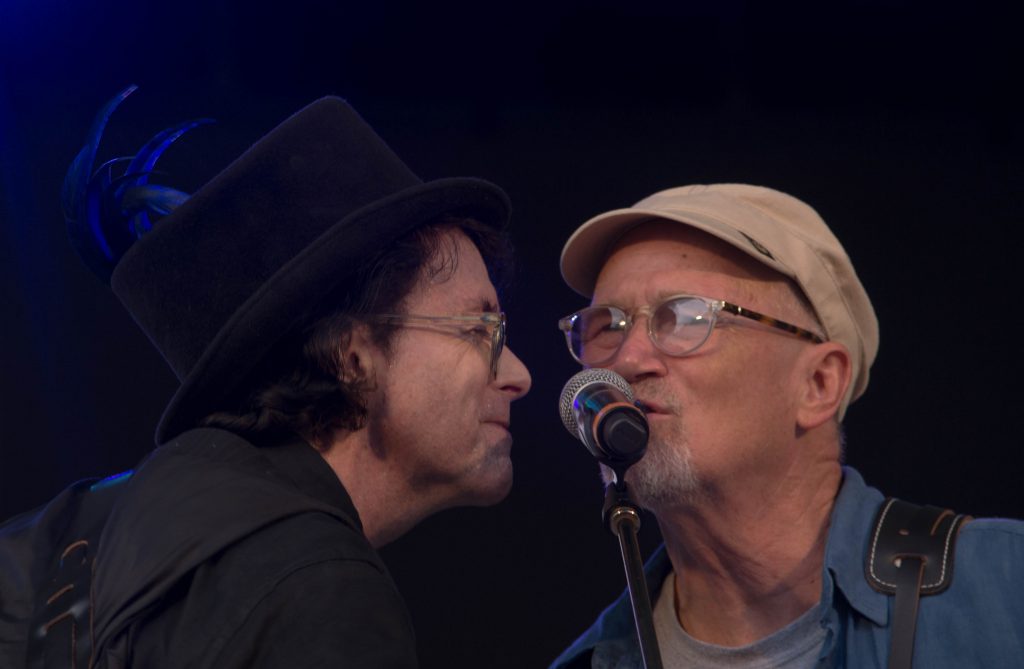

John Sebastian and Maria Muldaur at Central Park SummerStage, Aug. 12, 2018 (Photo © Jeff Tamarkin, used with permission)

John Sebastian was first out of the gate, backed by the house band led by the Kennedys, husband and wife Pete and Maura. It had to be “Summer in the City,” didn’t it? Is there another song that better captures the zeitgeist? Sebastian experienced throat problems some years ago so no, he doesn’t sound like he did when he was 22. It didn’t matter—the ebullience in his delivery, that omnipresent grin, those sideburns, it was all there. It was good to see him.

Barone and Marshall Crenshaw followed, harmonizing on a Buddy Holly song, “Learning the Game.” Buddy Holly? What does he have to do with Greenwich Village? He lived there toward the end, writing and demoing his final songs—he was gone before the ’60s even began, but he helped define what was coming.

So too did Dion DiMucci, the Bronx boy who gave up his seat on that plane that took Holly. Dion dug the Village too, and when he was done regaling about “Runaround Sue” and “The Wanderer,” he could be found singing the blues and folk songs in Village clubs. Barone more than did justice to “The Road I’m On (Gloria),” one of those songs, then brought out Happy Traum, the 80-year-old singer and guitarist who personifies the era as well as anyone. Happy was there when it was all happening, often backing Dylan before anyone had a clue what the kid from Minnesota was up to and later cutting records on his own and with his now-deceased brother Artie. Here Traum performed a homey take on Tom Paxton’s “Ramblin’ Boy,” an anthem that manages to remain chillingly effective even while feeling ever more removed from our world (does anyone still ramble?).

Richard Barone and Marshall Crenshaw, Central Park, NYC, Aug. 2018 (Photo © Jeff Tamarkin, used with permission)

The cast of Music + Revolution: Greenwich Village in the 1960s consisted of both veterans of the period and artists way too young to have experienced it first-hand. David Amram was at the heart of it. He’s 87 now, usually aligned with jazz but also with classical music, film music, folk and the Beat writers—a renaissance man if ever there was one. A multi-instrumentalist, he played piano for his first song of the evening here, Ochs’ “When I’m Gone,” shortly after Crenshaw also nodded to the late topical singer with the still-relevant “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” and Barone and others nodded to Tim Hardin. Another departed poet, Lou Reed, was the subject of tributes from, first, singer-songwriters Cindy Lee Berryhill and Syd Straw, and, later, performance artist Tammy Faye Starlite (who summoned the essence of Nico with the Velvet Underground’s “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and some hilarious patter) and music journalist Anthony DeCurtis, author of a recently published Reed bio, who actually sang (credibly), another Reed/Velvets staple, “I’m Waiting for the Man.”

Singer Nellie McKay, 36, was born years after the death of Richard Fariña, whose “Bold Marauder” she sang while accompanying herself on ukulele, and Jenni Muldaur arrived in 1965, the very year that Fred Neil recorded “A Little Bit of Rain,” the song she covered. Similarly, Jeffrey Gaines, who gave “From a Buick 6” from Highway 61 Revisited a fiery reading, was in diapers when Dylan cut the tune. The performances were all heartfelt and skillful, proving the resilience of the music that emanated from the Village-rooted scene back in the day.

What came across as the three-hour show rolled on—never flagging in passion—was how wide a net those original performers cast. Some preferred to reinvent the tunes of Appalachia or the Mississippi Delta; others rocked. If there was a thread linking it all, it was the raw honesty. The artists who made the music being feted here cared profoundly about what they said, in every line of every song, and how they said it. Whether a topical antiwar rant or the good-time music of Sebastian and the Spoonful, the connection between creators and those taking it all in ran deep.

Related: John Sebastian on the “Magic” of the Lovin’ Spoonful

Several of the evening’s more familiar “name” artists were saved for the last third of the show. Maria Muldaur, too, was in the thick of it all during the ’60s, with groups like the Even Dozen Jug Band (with Sebastian) and the Jim Kweskin Jug Band (with future husband Geoff Muldaur). She first chose a couple of Dylan songs, both of which—“License to Kill” and “Masters of War”—appeared on her 2008 Yes We Can! album. With Sebastian accompanying her on guitar, the singer injected the two tunes with a sizable dollop of blues, before wrapping their duo segment with Mississippi John Hurt’s “Richland Woman Blues,” which served as the title track for a Muldaur solo release back in 2001.

[/ot-video]

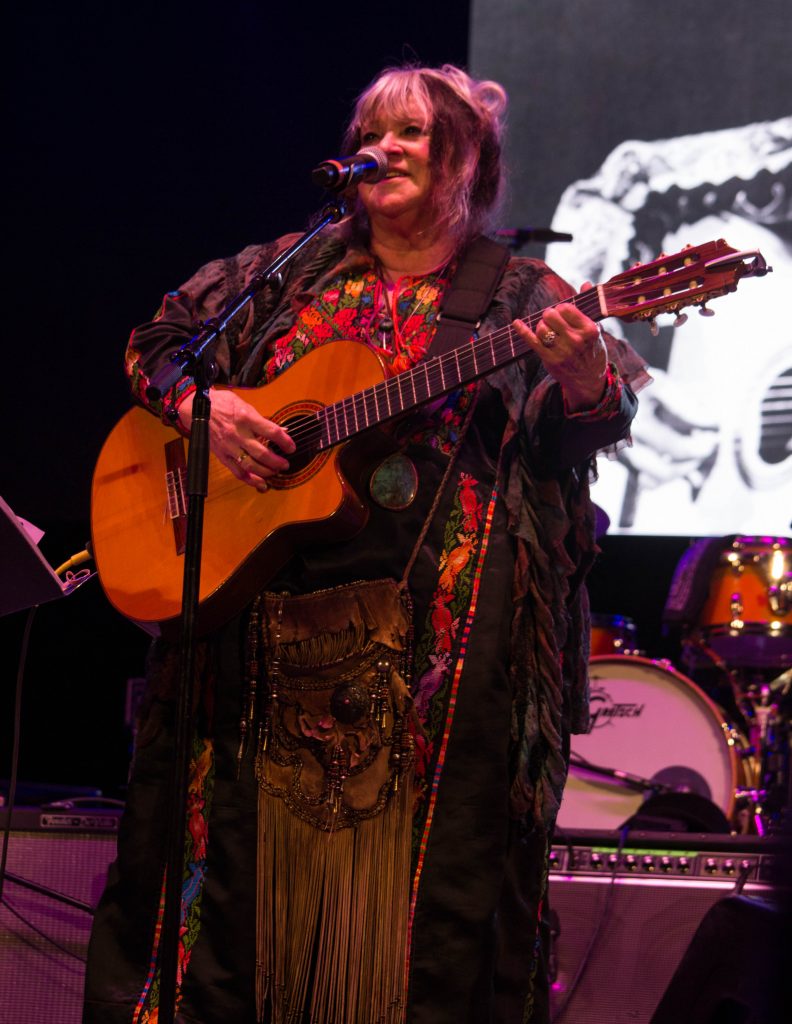

Melanie Safka, known professionally by her first name, did make the rounds of the Village clubs although she didn’t come into the public consciousness in a major way until she performed at Woodstock in 1969, a few years after the counterculture had already spread far beyond the confines of regional pockets like the Village and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. At her peak she personified the freewheeling, peace-and-love flower-child vibe and at 71 she’s lost none of that exuberance and positive spirit. She stuck to three of her trademark numbers at SummerStage—“Peace Will Come,” “Look What They’ve Done to My Song, Ma” and “Lay Down (Candles in the Rain)”—the latter featuring a chorus comprising some of the other women on the bill, and told of “leaving her body” during her Woodstock moment. Melanie’s singing voice is as formidable as it was in her 20s, if a little huskier, and she roused the crowd as soon as she opened her mouth and that booming sound came bounding out.

Related: Our interview with Melanie

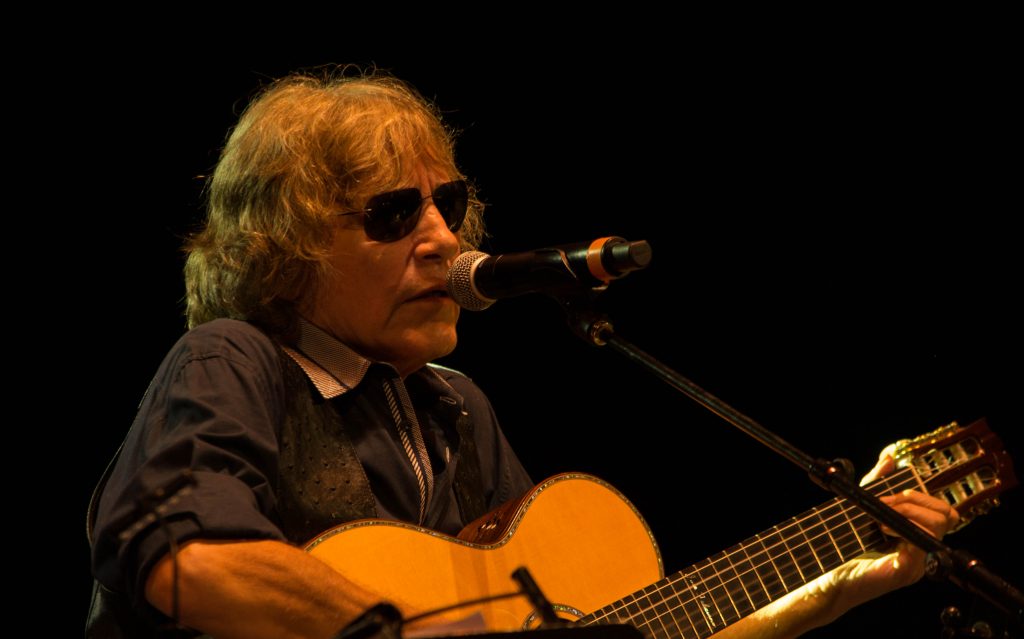

Jose Feliciano at Music + Revolution concert, NYC, August 2018 (Photo © Jeff Tamarkin, used with permission)

Jose Feliciano followed, which might have seemed an odd choice to some in the crowd, although he was very much a regular on the Village club circuit (as noted by Sebastian, who recounted how Feliciano’s talent got his coffers filled at the donation-dependent basket houses, leaving little for the others). Despite a surfeit of corny show-bizzy patter, even an off-color wife joke whose punch line hinged on his blindness, Feliciano was endearing—his takes on Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine,” the Beatles’ “In My Life” and the Doors’ “Light My Fire,” a top 5 hit for Feliciano in 1968, were spellbinding, particularly when he spilled out his trademark speedy solo guitar lines.

Related: Melanie interview: Woodstock and more

The final A-list star to grace the stage was Jesse Colin Young, former leader of the Youngbloods, a band that got its start in the Village before heading for San Francisco, where their popularity boomed. Young’s voice is as pristine and honeyed as it was back then, and his trio of tunes—“Four in the Morning,” the leadoff track from his 1964 solo debut, and “Sunlight” and “Darkness, Darkness,” both from the Youngbloods’ classic Elephant Mountain, were among the highlights of the long show.

Jesse Colin Young sings at the Music + Revolution: Greenwich Village in the ’60s concert, NYC, Aug. 2018 (Photo © Jeff Tamarkin, used with permission)

Sebastian returned as the show reached curfew time, making sure to get in two more Spoonful classics: “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?” and, of course, “Do You Believe in Magic?” (which, he noted, was based melodically on Martha and the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave”) Then, for the finale, Young returned to front and center for the only tune that—just as “Summer in the City” had to have started it—could have possibly ended it: “Get Together,” the Youngbloods’ signature hit, sung here by Young and the full cast.

If there was some naïveté or sadness to this group of performers and audience singing along, during these tense and trying times, to a song whose chorus implores us all to “Come on people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now,” it wasn’t noted. For a few hours on a lovely summer New York night, getting together didn’t seem like such a crazy idea at all.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.