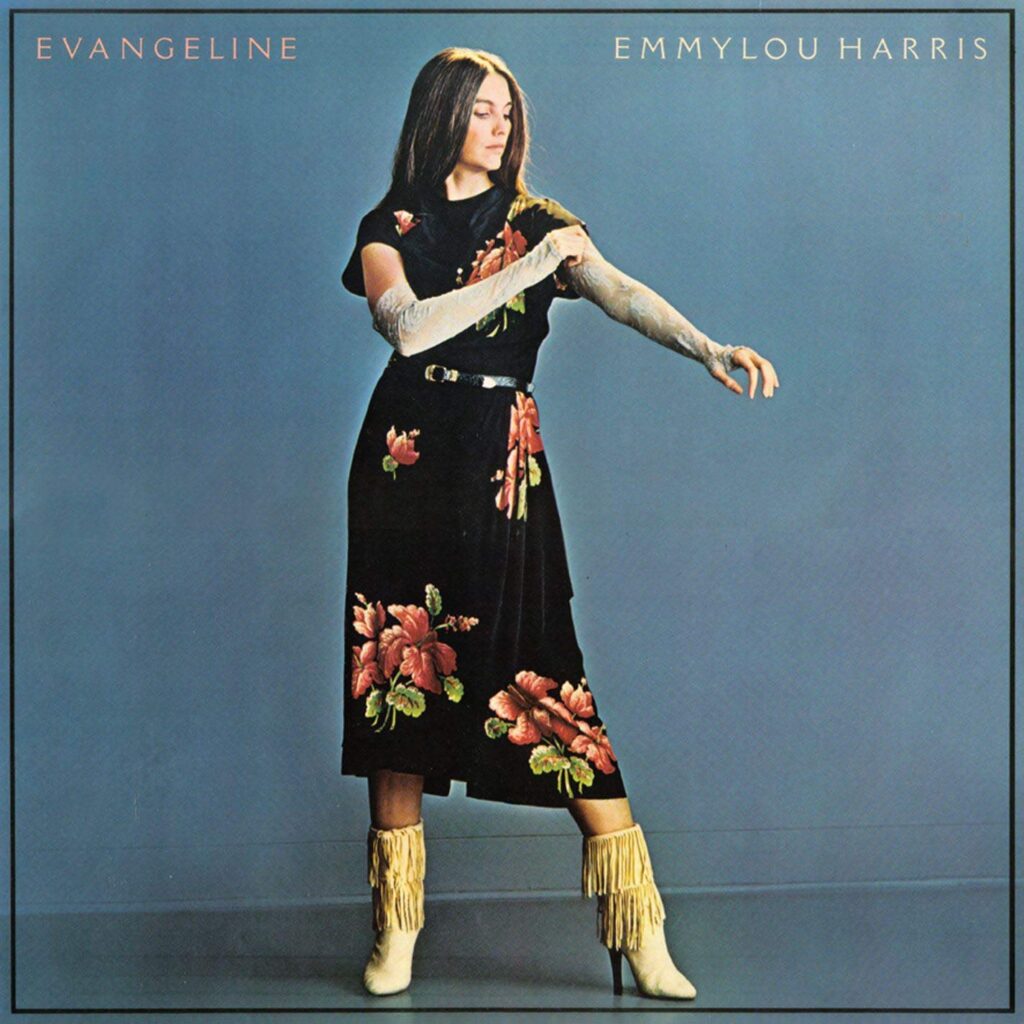

On paper, Emmylou Harris’s eighth album read like a blueprint for her continued reign as a contemporary country music queen. Released in late January 1981, Evangeline steered toward that era’s Music Row mainstream and away from the more traditional material explored on 1979’s Blue Kentucky Girl and the acoustic bluegrass focus of 1980’s Roses in the Snow. Past and current members of her redoubtable Hot Band were augmented by crack Nashville and Los Angeles pros, and the song list tapped familiar writers like Rodney Crowell and the late Gram Parsons, her mentor and musical soulmate, along with rock and folk tunesmiths including John Fogerty, James Taylor, Robbie Robertson, Little Feat’s Bill Payne, and Paul Siebel, with two pre-rock ’50s pop chestnuts offering piquant, if eclectic, detours.

On paper, Emmylou Harris’s eighth album read like a blueprint for her continued reign as a contemporary country music queen. Released in late January 1981, Evangeline steered toward that era’s Music Row mainstream and away from the more traditional material explored on 1979’s Blue Kentucky Girl and the acoustic bluegrass focus of 1980’s Roses in the Snow. Past and current members of her redoubtable Hot Band were augmented by crack Nashville and Los Angeles pros, and the song list tapped familiar writers like Rodney Crowell and the late Gram Parsons, her mentor and musical soulmate, along with rock and folk tunesmiths including John Fogerty, James Taylor, Robbie Robertson, Little Feat’s Bill Payne, and Paul Siebel, with two pre-rock ’50s pop chestnuts offering piquant, if eclectic, detours.

In the months following the album’s release, it landed her in the top 5 of the country album chart for the sixth time and earned her seventh RIAA Gold certification. One of the ’50s pop confections, an affectionate remake of the Chordettes’ 1954 version of “Mr. Sandman,” earned Harris her 14th top 10 country hit as well as her lone top 40 pop hit. Adult contemporary airplay added to the album’s luster, while international traction yielded success in foreign markets from Australia to West Germany.

Why, then, did Harris’ commercial impact diminish in the wake of Evangeline’s initial success? Emmylou Harris would not crack country’s top five albums for another 19 years before securing her stature as a pathfinder mapping where folk, country and pop would intersect in Americana. Hindsight offers two likely factors, starting with mainstream country’s rising crossover tide, a trend that accelerated with John Travolta trading disco couture for a Stetson in 1980’s Urban Cowboy. Music mogul Irving Azoff’s involvement translated to a soundtrack package that courted a denim counterpart to Saturday Night Fever with polished country-pop tracks from Mickey Gilley, Johnny Lee, Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton alongside Boz Scaggs and Bonnie Raitt.

Evangeline’s tilt toward the country mainstream was further enabled by a shelf already stocked with unreleased tracks. A closer listen argues that their commercial polish masked artistic missteps. Brian Ahearn, Harris’ producer since 1975’s Pieces of the Sky, her major label debut, and her husband since 1977, insured sonic continuity as did the musicians backing her, but the songs were orphans from various album sessions dating back to 1978’s Quarter Moon in a Ten Cent Town. Studio leftovers don’t necessarily reflect issues of quality control, especially when the artist and their team posed the caliber of musicianship in a storied cast of over 30 musicians on hand for Harris’ dates. But too often here familiar covers prove more faithful than exciting, while some of the set’s strongest performances buoy slighter material.

Harris’ association with Rodney Crowell had been mutually beneficial since she had recorded “Bluebird Wine” for Pieces of the Sky, tapping him to join the Hot Band. The Crowell song that opens Evangeline, “I Don’t Have to Crawl,” showcases Harris’ power as a ballad singer, rendered with a palpable ache in its epitaph for a lost love affair. Originally recorded in June 1978, the track’s crossover design is signaled by a cushion of strings and a few brief synthesizer accents that together blunt rather than enhance the singer’s audible heartbreak, dating its reverb-drenched sound. Released as the album’s second single, “…Crawl” peaked outside country’s single charts with pop airplay that still fell short of success, falling between those component genres rather than crossing over them.

Her fealty to Gram Parsons had previously led Harris to record six songs written or co-written by the former Byrd and Burrito Brother, offering a benchmark that the seventh Parsons cover offered here fails to meet. “Hot Burrito #2,” written with Chris Etheridge for the Burritos’ debut full-length, The Gilded Palace of Sin, closely follows its original arrangement without matching its tough attack, plodding where Parsons and his bandmates had strutted. It’s a performance that’s workmanlike but unexciting – a textbook candidate for the cutting room floor.

Covers of John Fogerty’s Creedence classic, “Bad Moon Rising,” and Bill Payne’s “Oh Atlanta,” one of Little Feat’s Southern-fried crowd favorites, likewise receive solid readings without offering any fresh insights, while James Taylor’s “Millworker” diverges from personal confession to sketch a more elaborate narrative closer to traditional folk ballads. Harris’ earnest performance can’t elevate Taylor’s song beyond its dull melancholy. All three of these interpretations mine proven hitmakers to diminished effect, undercut in their execution.

Leave it to a lesser-known folk-rock songwriter, Paul Siebel, to offset those disappointments with a haunting folk ballad that realizes the narrative drama Taylor’s work failed to conjure. “Spanish Johnny” fleshes out a 1917 Willa Cather poem to recount the violent life and death of its titular anti-hero, a murderous cowboy. Harris and Waylon Jennings duet against a brooding arrangement that animates Johnny’s devotion to his treasured mandolin through Ricky Skaggs’ own plangent mandolin flourishes and Mickey Raphael’s mournful harmonica. The piece is a worthy companion to Townes Van Zandt’s classic “Pancho and Lefty,” which Harris had recorded in 1976. Siebel’s sadly underestimated career also echoed Van Zandt’s in his struggles with depression and substance abuse.

The album is also redeemed by the Robbie Robertson title song, introduced as part of a suite of songs performed on an MGM soundstage as an appendix to the all-star sendoff given The Band in The Last Waltz. Harris appeared as guest vocalist alongside Rick Danko and Levon Helm in that original version of Robertson’s picaresque romantic fable, loosely modeled on an 1847 poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow set a century earlier amid the expulsion of French-speaking Acadians from Nova Scotia during the French and Indian War.

Robertson’s lament relocates its tragedy to the Acadians’ exiled home, Louisiana, with its lovesick heroine pining for the riverboat gambler lured away by the promise of winnings only to drown when the “Mississippi Queen” sinks. The arrangement crafts a stately waltz from Skaggs’ overdubbed fiddles, Albert Lee’s lean Telecaster figures, and acoustic rhythm guitars to frame Harris’ lovely, homespun lead vocal and lush, soaring harmonies on the choruses supplied by Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt, prefiguring the three singers’ long planned but repeatedly delayed Trio project, which would finally surface six years later.

Harris’ collaboration with Parton and Ronstadt easily propelled their lively resurrection of “Mr. Sandman” (formalized here as “Mister…”) to hit status. Their creamy vocal blend is sufficient cause for smiles while cheerfully corny lyrics invite added ironic mirth in their pre-feminist ardor, exemplified by the rhyming name check of “Pagliacci” and “Liberace” as romantic idols eclipsed by Elvis, Brando and other ’50s heartthrobs not long after the Chordettes’ hit fell off the singles chart.

The uncomplicated delight delivered on “Mister Sandman” offers an ironic victory for Harris, whose body of work is otherwise built on a foundation of thematic depth and emotional pain. Its specific nostalgia for the 1950s meanwhile reappears in the album’s most surprising highlight, a soaring version of “How High the Moon” that salutes Les Paul and Mary Ford’s 1951 take on the 1940 jazz standard previously cut by Benny Goodman, Stan Kenton and Ella Fitzgerald. The Paul/Ford version was an early showcase for guitarist, luthier and inventor Paul’s pioneering multi-track production techniques, overdubbing his own multiple guitars to erect its instrumental framework, with wife Mary Ford laying down its harmony vocals on three passes.

Related: Our Album Rewind of 1987’s Trio with Parton, Ronstadt and Harris

Emmylou Harris nails the choral harmonies with support from Cheryl Warren and Sharon White, but the track’s excitement radiates from a virtuosic instrumental summit juggling Tony Rice’s flat-picked acoustic guitar, Ricky Skaggs’ mandolin, Albert Lee’s Telecaster, and Jerry Douglas’ dobro, all traveling with dazzling speed and precision. With Brian Ahern on arch-top rhythm guitar, the song unspools as a giddy round robin that echoes Django Reinhardt as much as Les Paul and Chet Atkins.

On balance, Evangeline is least convincing when the material courts the mainstream, paling beside the leaner bluegrass design of its predecessor, Roses in the Snow. Harris’ subsequent ’80s albums would prove more cohesive, while her overall song sense would continue to yield thoughtful choices in material that drew from rock, pop and standards in addition to country and folk sources. She would step up her own songwriting for 1985’s The Ballad of Sally Rose, an ambitious concept album loosely inspired by her relationship with Gram Parsons, while 1987’s Angel Band offered a set of traditional gospel songs recorded mostly live with an intimate acoustic ensemble, earning one of her three dozen Grammy nominations.

Despite the virtuosic musicianship of her touring ensembles including the Hot Band and the Nash Ramblers, and her influence on country’s neo-traditionalist element, Harris’ commercial standing receded by the early ’90s despite no discernable dip in artistry. Alongside the arena-ready crossover country served up by Garth Brooks and Shania Twain, Harris’ music was merely life-sized. Frustrated at country radio’s cooling reception, she embarked on a bold reinvention of her style with 1995’s Wrecking Ball, produced by Daniel Lanois, projecting a new synthesis of folk and alternative rock elements that served as a beacon for Americana’s coalition of roots music artists.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Harris’ 1976 release, Luxury Liner

Watch Emmylou Harris and The Band perform “Evangeline” in The Last Waltz

Harris recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationGreat Read! Thank you – somehow I missed this album – I’ll fix that in a hurry –

Well written – great info –