Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival: First-Hand Stories

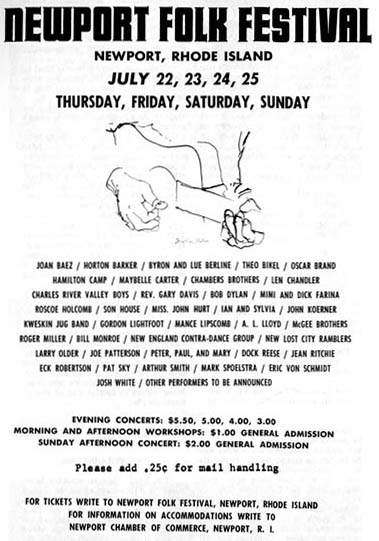

by Rob Patterson Nearly five years after the film was first announced, the Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, finally opened on Christmas Day 2024. The movie, from Searchlight Pictures, was directed by James Mangold, who also wrote the screenplay with longtime film critic Jay Cocks, based on Elijah Wald’s book, Dylan Goes Electric! It stars Timothée Chalamet, who was 28 years old during the filming. A Complete Unknown is set during Dylan’s days as a Greenwich Village folk singer in the New York City music scene of the early ’60s, culminating with his decision to play a transformational electric set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, which at the time was seen as one of popular music’s most shocking events. The film takes its title from the iconic lyric from 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Nearly five years after the film was first announced, the Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, finally opened on Christmas Day 2024. The movie, from Searchlight Pictures, was directed by James Mangold, who also wrote the screenplay with longtime film critic Jay Cocks, based on Elijah Wald’s book, Dylan Goes Electric! It stars Timothée Chalamet, who was 28 years old during the filming. A Complete Unknown is set during Dylan’s days as a Greenwich Village folk singer in the New York City music scene of the early ’60s, culminating with his decision to play a transformational electric set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, which at the time was seen as one of popular music’s most shocking events. The film takes its title from the iconic lyric from 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone.”

A Complete Unknown earned eight Academy Award nominations including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor. Though it although it didn’t win any, it was both a critical and commercial success, earning more than $140 million at the box-office.

Exactly what transpired on Sunday, July 25, 1965, at the Newport Folk Festival when Dylan first took to the stage with an electric band has been shrouded in the mists and shifting winds of memory, perspective and legend. Elijah Wald’s book Dylan Goes Electric! offers an accurate account of the iconic concert for the history books.

Yet still there is a spectrum of experiences and recollections regarding one of the pivotal musical moments of 1960s classic rock, if not of all modern popular music. Just as the 1960s was a decade of musical and cultural change overall, Dylan plugging in at Newport signaled a monumental shift in the nature and atmosphere of the decade itself at almost its exact midpoint.

We offer here the recollections of some of the many thousands who were there: from on the stage playing with Dylan, working the show as part of his crew, a fellow member of the folk community and industry, and two who were in the audience as the show unfolded. Interspersed are videos of some of the music he played that night, along with other memories and reflections. Memories and accounts may differ; but this is the truth of Newport ’65 as seen and recalled by those who experienced it.

♦ ♦ ♦

As a Chicago teen, keyboardist Barry Goldberg sat in with Muddy Waters, Otis Rush, and Howlin’ Wolf. His first recording session was Mitch Ryder’s “Devil With a Blue Dress On.” He co-founded the Goldberg/Miller Blues Band with Steve Miller and the Electric Flag, played on the famed Super Session album with Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper and Stephen Stills, and has written songs recorded by and played sessions with many notable musical artists. Not long ago, he was part of the band The Rides, with Stephen Stills and Kenny Wayne Shepherd, whose second album was released in 2016.

As a Chicago teen, keyboardist Barry Goldberg sat in with Muddy Waters, Otis Rush, and Howlin’ Wolf. His first recording session was Mitch Ryder’s “Devil With a Blue Dress On.” He co-founded the Goldberg/Miller Blues Band with Steve Miller and the Electric Flag, played on the famed Super Session album with Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper and Stephen Stills, and has written songs recorded by and played sessions with many notable musical artists. Not long ago, he was part of the band The Rides, with Stephen Stills and Kenny Wayne Shepherd, whose second album was released in 2016.

[In May 2024, Goldberg went public about his cancer battle; he died in January 2025.]

I was playing briefly with the Butterfield [Blues] Band in Chicago. They invited me to come to Newport with them. We drove to Newport, Rhode Island. And when we got there, Paul’s producer – they were signed to Elektra Records; his name was Paul Rothchild – said, “I don’t hear keyboards with the band… at all.” So I was stranded without a gig and really freaked out and bummed out that I wasn’t going to get to play.

Newport was beautiful; Joan Baez was running around barefooted. I’d never seen that before coming from Chicago. Everyone was sleeping in these big mansions on cots. It was amazing. I didn’t even realize it at the time.

Michael [Bloomfield] had known Bob from the recording sessions [they did] a few months earlier, when they did “Like a Rolling Stone.” Michael had played me “Like a Rolling Stone” a few months earlier and I sort of knew the song. Bob wasn’t sure who was going to show up or what was happening for his performance. He was preparing to do something really new, an electric kind of music, which no one really knew at the time.

So Bob said to Michael, “It would be great to get a keyboard. Do you think he [Goldberg] would play with us?” And Michael said, “Barry’s great,” and introduced me. And I said, “I’d love to, are you kidding? This would be amazing.” So I went from not playing with Butterfield to playing with Dylan. I knew who he was; it was a big deal.

We did a little soundcheck and I thought it was really cool. Then [keyboardist] Al Kooper showed up, so it happened accidentally that it was two keyboards. Jerome Arnold, the bass player for Butterfield, couldn’t get the chords to “Like a Rolling Stone” down because they were different. So Al played bass on that.

We did it the next night and I sensed that this was really something special. Bob was wearing black with a black guitar and Michael was ready to go. [Dylan] was doing something new and controversial, and taking another giant step in his career. I was surprised that it was a mixed reaction. People like to think it was all boos but it wasn’t; I did hear some cheers. There were some people really digging it, especially “Like a Rolling Stone.” I heard it later in the Martin Scorsese No Direction Home [documentary], it sounded pretty cool to me. It was a really good live version of that song.

What Bob really did at that moment was create folk-rock. We were on a mission, and it was an important moment. We really didn’t realize until later just what a pinnacle moment it was in rock ‘n’ roll. What Bob did was create a whole different kind of music. I’ll never forget that.

Related: Dylan in ’65: Evolving to electric

♦ ♦ ♦

Jonathan Taplin was an 18-year-old associate of Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman who was at Newport road-managing another of Grossman’s clients, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, and was pulled in to assist with the Dylan set. He later road-managed Judy Collins, Bob Dylan and the Band and Janis Joplin, and in 1971 helped George Harrison stage the Concert for Bangladesh. In 1973 he produced Martin Scorsese’s first feature film, Mean Streets. He is a clinical professor of communication a the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and director of USC’s Annenberg Innovation Lab.

Jonathan Taplin was an 18-year-old associate of Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman who was at Newport road-managing another of Grossman’s clients, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, and was pulled in to assist with the Dylan set. He later road-managed Judy Collins, Bob Dylan and the Band and Janis Joplin, and in 1971 helped George Harrison stage the Concert for Bangladesh. In 1973 he produced Martin Scorsese’s first feature film, Mean Streets. He is a clinical professor of communication a the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and director of USC’s Annenberg Innovation Lab.

On Saturday afternoon the Butterfield Blues Band played in a workshop in an open field and [folklorist] Alan Lomax kind of freaked out and tried to unplug them; it was the first electric band at Newport. Lomax, who was kind of the guardian of the old blues guys, was very upset and he and Albert got into a fight. Albert, Geoff Muldaur and myself went to the backstage tent after that and Albert told this story to Bob, and Bob kind of laughed. I think that’s when he got the idea that he should go electric. He wanted to kind of stick it to the old guard.

The band was very publicly assembled. It was mostly the Butterfield guys: Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold, the rhythm section of the Butterfield band, and Mike Bloomfield. Then Al Kooper was brought in from New York on a private plane. There was a very quick rehearsal, not very organized. There was a sound check on Sunday afternoon, which was also very disorganized. Peter Yarrow [of Peter, Paul and Mary] somehow appointed himself to be the sound mixer, which was also kind of a disaster because he didn’t know anything about electric music; they did acoustic stuff. They never really got the mix right.

Bob went on on Sunday night…. I went down in front where there was a pit where the photographers stayed. It was very clear from right off the bat that the mix was completely f**ked up. The guitars were really loud, and you could not hear the bass, and Dylan’s voice was completely drowned out.

They did “Maggie’s Farm” and there was a smattering of applause and some boos, but not a lot. And then the next song they got into the mix seemed to get a lot worse. Bloomfield was kind of leading the band and Jerome and Sam had never played that kind of music. Bloomfield kept turning up his guitar to compensate. They went into “Like a Rolling Stone,” and it just never got itself together. A lot of people were booing, and then Bob just said f**k it and unplugged his guitar and walked off stage. Peter Yarow kept asking Bob to come back on.

He got an acoustic guitar and came back up, and the spotlight went on him, and the audience started cheering like they had won, you know? They had convinced him to get rid of the rock ‘n’ roll. He yelled, “Does anyone have a E harmonica?” A bunch of harmonicas came flying up onstage and he clipped one on, and he played “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” Then he just walked off stage.

Watch footage from The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Live at Newport Folk Festival 1963-1965 here.

♦ ♦ ♦

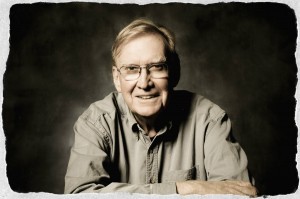

Bill Kirchen, known today as “The Titan of the Telecaster,” was an Ann Arbor, Mich., high-schooler and budding folk banjo and guitar player who turned 17 years old four days after seeing Dylan at Newport in 1965. He was a founding member of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen and has recorded acclaimed solo albums. he regularly crosses North America on tour with his band Too Much Fun.

I went to Newport in ’64 to see Dylan and everybody, and I went back in ’65. I had just found out about Butterfield and was excited to see him with Bloomfield and Jerome Arnold and Sam Lay. [Dylan’s] “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was on the radio already, so him being electric was not news.

I have to say I loved every minute of it. I wasn’t a savvy enough musician to know all the problems they were having. Bloomfield had always made comments that Jerome couldn’t really learn to follow the changes, but so what? I never ever really heard anyone boo, so when this whole thing showed up about Dylan being booed at Newport, I was always completely dumbfounded. I thought, how on earth could I have I missed that?

I look back at Newport being the biggest influence on my whole life, and Dylan is central to it. I loved Bob Dylan and I still do.

Watch Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman and Newport Folk and Jazz Festivals promoter George Wein discussing Dylan at Newport ’65 & Dylan performing “Maggie’s Farm”

♦ ♦ ♦

Noë Gold is the Founding Editor of Guitar World magazine, has held editing positions at Crawdaddy, the Hollywood Reporter and Movies USA, and been a columnist for the Village Voice and the New York Daily News. He is the author of articles and books on the music of Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, Ry Cooder, Miles Davis, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Albert King, among others.

Noë Gold is the Founding Editor of Guitar World magazine, has held editing positions at Crawdaddy, the Hollywood Reporter and Movies USA, and been a columnist for the Village Voice and the New York Daily News. He is the author of articles and books on the music of Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, Ry Cooder, Miles Davis, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Albert King, among others.

I was just as excited to hear the sounds of Butterfield booming across the PA as I was with the anticipation of seeing Dylan. Then when I found out they were going to be the back-up band for Dylan, that was the superfecta.

What I remember about the night itself was lining up with all these ragtag people and the chatter that was going on. I wound up being closer to the back, and as you were going up the hill you could hear the unmistakable sounds of the amplified harmonica and the booming bass and Mike Bloomfield’s riffs screaming out.

The anticipation was: What is Dylan going to be blasting us with? It wasn’t the folk purist thing. He was going to be messing with the Holy Grail that the Newport quote-Folk-unquote Festival was supposed to be about.

To me, it was great: “Like a Rolling Stone,” he was belting it out. Then we started to hear these sounds and I thought they were saying, “Down in front!” so they can see what’s going on. It wasn’t what was supposedly reported where the crowd booed the electric guitar numbers.

He’s getting the same reaction now that he did 50 years ago [by regularly rearranging his songs]. To me, as a lifelong fan, it’s all the same thing, a continuum.

♦ ♦ ♦

Jim Rooney is a folk singer, record producer and music publisher who ran the famed folk music venue Club 47 in Boston in the 1960s and served on the Newport Folk Festival Board and as its talent coordinator starting in 1966. He has produced albums and projects by Nanci Griffith, John Prine, Townes Van Zandt, Bonnie Raitt and others. He recently published his autobiography, In It for the Long Run: A Musical Odyssey.

Nobody had ever seen him except playing with an acoustic guitar and his little dungaree jacket and his Woody Guthrie persona, And here he was in high-heeled boots and a polka-dot shirt and everything, and he was a rock ‘n’ roll guy, which is actually where he started before he came to New York. It was loud, it was rock ‘n’ roll, and there was a definite immediate reaction in the audience. Some people really loved it and some people couldn’t stand it. And they let him know.

Ralph Rinzler [of the Newport board] had asked me to write a critique of the festival as an outsider and someone who was going to get involved in the festival. So I did. Rinzler sent it to Sing Out! magazine, and it actually became public; it wasn’t intended to be. I wrote that, well, sure, Bob might have seemed rude, and not in the spirit of how Pete Seeger had set the evening up with his usual messages of hope and brotherhood and whatnot. Bob’s thing didn’t really fit into that… what does it feel like to be on your own, like a rolling stone, with no direction home? He was basically saying don’t look to me to solve your problems. To me that’s what the message was. At the end of this critique I said, well, this is what we have artists for, to shake us up, and that’s the point.

Related: Our interview with Elijah Wald, author of Dylan Goes Electric [The acclaimed book is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.]

7 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI just came back from Newport Folk Festival 2017. There are three major stages, Quad, Harbor, and Fort. I would like to know the various stage configurations in 1965 and upon which one Dylan played.

It wasn’t there. There was an outdoor stadium very near downtown on the main street that went to the beaches. I believe if was called Freebody Park.

I was there. There was a lot of booing. Really angry booing. Some people were booing at the leather jacket before they played a note. People can spin it any way they wan’t. And he did 2 acoustic songs, not 1.

I was there and killing to be a rock and roll musician. When Dylan got booed me and bandmates got into a shoving semi-punching match with folkie purists in front of us.

I was so much older then.

I wouldn’t walk across the street to watch Bob Zimmerman perform for free. He totally disrespects his audiences, plays arrangements of his songs so that no one can recognize them, doesn’t talk to the audience, and is a horrible showman. Plus, he’s a really lousy singer. On the other hand, I have great respect for his songwriting ability. He’s written songs that will last forever. Props to him for that. It’s very much a mixed bag with that guy. The songs are immortal, but his performances are worthless.