This interview first appeared here in 2015. “What I do in my books is try to make the world more complicated, not simpler,” says Elijah Wald, “and no one on Earth is more complicated than Bob Dylan.”

This interview first appeared here in 2015. “What I do in my books is try to make the world more complicated, not simpler,” says Elijah Wald, “and no one on Earth is more complicated than Bob Dylan.”

Occasionally, Wald stirs up some fuss. In 2009, he rattled some cages when he wrote How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll: An Alternative History of Popular Music.

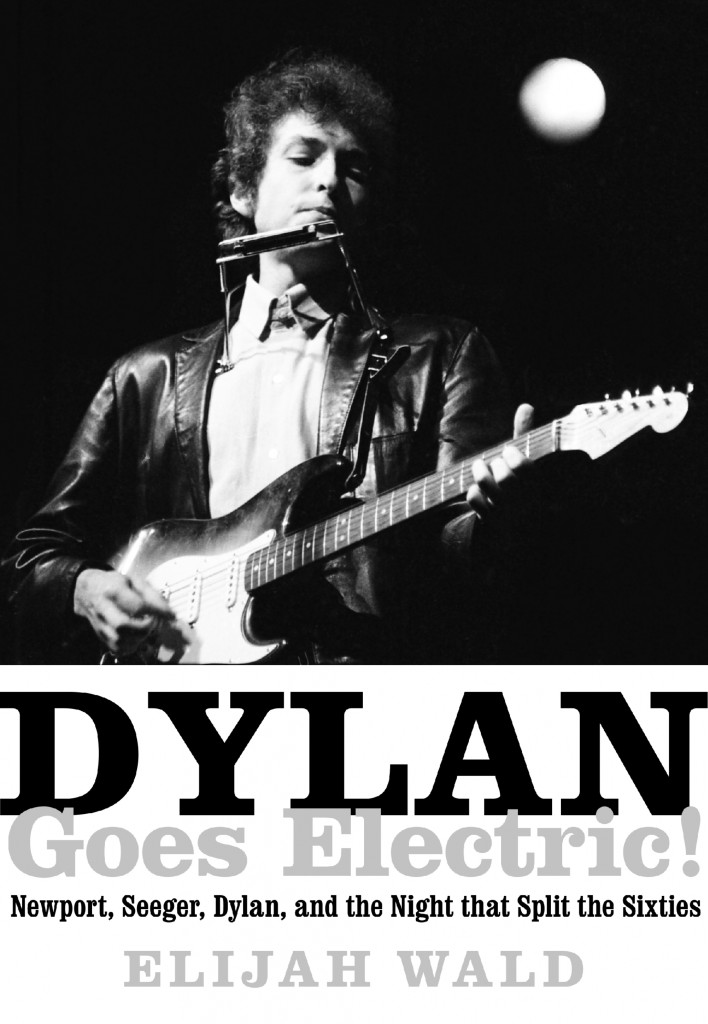

In 2015, Wald, published the book, Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night That Split the Sixties, focusing on one of the most iconic controversial (or controversially perceived) concerts in the last half century of rock music history. [Ed., the screenplay for the 2024 Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, is based on Wald’s book.]

Wald is not saying everything you think you know about that night at the Newport Folk Festival, on July 25, 1965, is wrong. But he is saying what Dylan did that day – plugging in to play three songs with a loud rock band – and what the audience did – boo or cheer? – is a lot more tangled than popular myth has it.

Wald, based in the Boston area, is a singer-guitarist and musicologist. Dylan Goes Electric! was his 12th book. Wald’s forte is weaving myriad details into a larger context, digging into archival sources and finding fresh voices. Thus, while Dylan’s electric set is the nexus of this book (and its selling point), the author writes about how the Newport Folk Festival evolved, how it was positioned in the culture and what was going on outside of it.

As to Dylan, it’s fair to say most people’s perception has been that Dylan was roundly booed for his temerity and his electricity. That had been Wald’s assumption, too, before embarking upon the project.

“There had been an argument on the International Association for the Study of Popular Music email list,” Wald says, about what sparked his desire to investigate, “and it was all these academic music scholars just getting irate at each other as to whether Bob Dylan really got booed.

“I had just read Bruce Jackson’s book, The Story is True. He’s a very prominent folklorist, but was also on the board of the Newport Festival. He was the guy who had all the [concert] tapes until he gave them to the Library of Congress a couple of years ago. He wrote a book about how myths happen in which he characterized Dylan getting booed at Newport as a myth.

“He said, ‘I was there, I’ve got the tapes, it didn’t happen.’ Since he was there and he was a folklorist and had the tapes, I figured he was probably right. As it turns out, he wasn’t. I should add that Bruce’s book is about the complexities of memory and eyewitness testimony, and though I reached a different conclusion, the story is infinitely messy and I consider his work a model for what I was trying to do in this book.

“By Dylan’s own definition,” Wald writes, “he had ceased to be a folksinger when he stopped singing old songs. What was changing now was his audience, his circle of acquaintances and the instrumentation – he saw those as additions, not subtractions.”

It’s not so much that Dylan’s music was electric and amplified; the Newport Folk Festival had welcomed that before and did in 1965. It was just that Dylan hadn’t done it and a lot of fans wanted to keep him in a folkie box he had no desire to dwell in any longer.

In retrospect, one thing that Dylan’s seemingly contrarian and confrontational set did is it laid the foundation for the twists and turns he would take throughout his career, very much including who he is today. Dylan tours constantly – the Never Ending Tour – and plays very few songs from what old fans might consider his glory days. If he does play a ’60s classic such as “Like a Rolling Stone,” he reworks it radically. He’s always done this, but in the 21st Century in many ways he’s bar-band Bob, singing gruff, not (or barely) touching his guitar, sticking to keyboards and contentedly playing everything in a bluesy, R&B groove.

“He’s completely cheerful in exactly that role,” says Wald.

“There’s this moment in [Dylan’s memoir] Chronicles where he’s about to start this tour with the Grateful Dead and he’s going to quit because he just can’t do this anymore. And he walks past this bar and there’s this little band – it’s actually a jazz trio – and he’s sitting there having a beer and he goes, ‘Wait a minute, I used to be able to do that. I’ll start doing that again and just be a musician.’ It was an absolutely conscious decision: ‘I’m not a genius anymore, I’m sick of that, I don’t have that anymore, I’m just going to be a bar band.'”

♦ ♦ ♦

Best Classic Bands: In reading Dylan Goes Electric!, we find out there’s lots of complexities and gray areas about how folk music and rock music intersected or collided in 1965, as well as the tension within the folk world.

Wald: We all have confused “The 60s” with the second half of the ‘60s. It’s so easy to forget that the first half of the ’60s was just a different universe. I think one thing people need to understand is a lot of people were upset before Dylan walked on stage with his electric guitar. About all kinds of things. The world was changing. The end of the folk scene was in the air for anyone who was paying attention. Once the Beatles hit, the writing was on the wall. And the star thing had hit – and there were all these people who had come to Newport just to see Dylan or just to see Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary, and who essentially had come for the party and had no interest in the traditional folk music that Newport had kind of been created for. There were a lot of people that already felt that their little utopia had been invaded by a bunch of essentially dumb pop fans. This was the icing on that cake for some people.

Wald: We all have confused “The 60s” with the second half of the ‘60s. It’s so easy to forget that the first half of the ’60s was just a different universe. I think one thing people need to understand is a lot of people were upset before Dylan walked on stage with his electric guitar. About all kinds of things. The world was changing. The end of the folk scene was in the air for anyone who was paying attention. Once the Beatles hit, the writing was on the wall. And the star thing had hit – and there were all these people who had come to Newport just to see Dylan or just to see Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary, and who essentially had come for the party and had no interest in the traditional folk music that Newport had kind of been created for. There were a lot of people that already felt that their little utopia had been invaded by a bunch of essentially dumb pop fans. This was the icing on that cake for some people.

BCB: And complexities as well, of course, about the reaction to Dylan’s set.

Wald: Absolutely. I know people who were there who will absolutely swear no one was booing. On the other hand… I haven’t actually talked to anyone who says they booed, but most of the people I’ve talked to say there were people around them booing and some of the people were definitely sympathetic to that point of view. It’s not hard to find people who were upset.

BCB: As to Dylan himself, there are so many perspectives on why he did what he did and how he felt afterward. Was he happy? Was he crying? Was he hurt? Was he drunk, as he’s quoted as saying at one point?

Wald: The one thing that everyone seems to agree on was he was startled; he didn’t expect that to happen. I think the other thing that’s left out of the story by people who want to tell it oversimplified is the band really was under-rehearsed and the set really was kind of a mess. Whatever else is to be said about it, it is a set where from his going on stage to him finally leaving was 35 minutes and 10 of those minutes was dead space.

BCB: A lot of fumbling about looking for guitars and harmonicas, tuning up….

Wald: And ignoring the audience completely. It was very hard to understand for people who’ve lived, as you and I have, with what Dylan does on stage now – Dylan never talks on stage and hasn’t for years – but understand how discomfiting that was because Dylan used to kid around, joke and chat with the audience. People were used to him being bouncy and funny and friendly. I think that’s also part of the story, the extent to which he was cutting himself off from them, and I don’t see how anyone could have felt otherwise.

BCB: You write about the tour that followed Newport, where he was booed quite frequently. He would do an acoustic set and then come back with an electric set and a lot of people took umbrage with that.

Dylan appearing acoustic at an earlier Newport ’65 workshop (Photo: Joe Alpers; courtesy of Elijah Wald)

Wald: Yes, absolutely. A lot of people I have to think at some point went in order to take umbrage, because it became news. Certainly by the time he’s on the English tour that was captured on the unreleased (but on YouTube) film, Eat The Document, there are people showing up knowing that they’re angry. The other thing is I think it was really liberating for him. After these audiences that had just sat staring open-mouthed at him as a prophet, I think having audiences booing was a huge relief in a way. I don’t have to be that guy anymore.

BCB: One of your key points is that before he was “discovered” as a folksinger, Dylan was a blues-rocker.

Wald: Listening to the unreleased Freewheelin’ sessions [demos of Dylan’s second album] I had no idea how much further he took the blues thing after the first album and before he made that left turn into being a singer-songwriter. I was impressed with the quality of the guitar playing and the singing. And some harmonica playing in the early days – straight-up blues harp.

He was playing with rock ‘n’ roll energy back then. I had bought the Woody Guthrie myth, the idea that he came to New York playing like Woody Guthrie. And that was one of the things that interested him, but what made people go wild for him in that moment was that he was bringing rock ‘n’ roll energy into the folk scene. So it was sort of not surprising that he got himself a band.

There’s that quote from Peter Stampfel [of the Holy Modal Rounders]. He said that the two loves of his life were old-time music and rock ‘n’ roll and they were really the same thing. When he first said it I went, “Huh? Oh, come on!” But the more I listened to the early Dylan the more I saw he was playing with rock ‘n’ roll energy back then.

BCB: Neither was he, it turns out, the lefty, anti-war songwriter many people saw him as after “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Masters of War.”

Wald: The thing that I hadn’t realized until I looked at the numbers is he was a political songwriter for maybe a year-and-a-half. It’s a tiny, tiny stretch. By the time people recognized him as a political songwriter he was already past that. By the time ‘The Times, They-Are-A-Changin’” came out, he wasn’t writing that stuff anymore. That startled me as well, how briefly he was doing that.

BCB: You went not far afield in the book, but far enough afield to make Dylan’s set part of an overall context, as you write about what else was going on in the world, musical and otherwise. How and why did it expand this way?

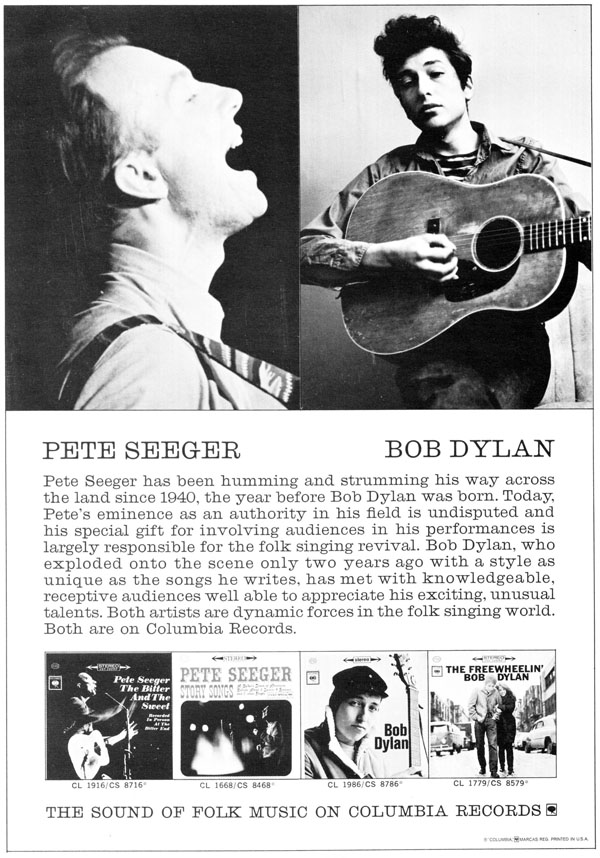

Wald: The proposal I made was much, much simpler, but part of what [writing this was] just the realization that I had to be able to explain who Pete Seeger was. That if people didn’t understand that, they weren’t going to understand what happened that night.

Wald: The proposal I made was much, much simpler, but part of what [writing this was] just the realization that I had to be able to explain who Pete Seeger was. That if people didn’t understand that, they weren’t going to understand what happened that night.

I didn’t know a lot of this background going into it, the aura and the power in the folk music world that Pete Seeger had.

One of the big things that I realized as I started writing about this, is this particular story has almost always been told by rock fans. And they started telling the story immediately and their spin with it – and I completely sympathize with them – was that the stupid folkies had got their comeuppance, and had been shown up as a bunch of closed-minded, annoying purists that the rock fans always thought they were. (Laughs). And that sort of became the story.

BCB: You don’t debunk that exactly, you just expound upon it.

Wald: No. I understand that point of view, but I think the huge problem with that point of view is those people don’t understand who Pete Seeger was. They think of Pete Seeger as “Oh yeah, the old guy who led sing-alongs.” And that is a profound misunderstanding. Dylan certainly knew who Pete Seeger was in the way I frame it. To Dylan, Pete Seeger was a hero and that never changed.

“So that was a big part of it. Part of it, too, came out of the other book I did, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll, which I spent a lot of time in that book just getting the context for that period. It’s so hard for a lot of people to remember the Beatles were a dumb rock band for a while. The idea that when Dylan went electric it’s still six months before Rubber Soul and the Beatles are essentially a band that teenage girls liked. We’ve so lost that period of the Beatles in our memories.

♦ ♦ ♦

Time for a brief Beatles interjection. Wald and I talked about How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll several years ago, and he said, “Please write that I do not hate the Beatles. I grant you ‘destroy’ is a provocative word. The title is an attempt to make people pick up the book. But if Paul McCartney picked it up, I don’t think he’d disagree. He is truly conscious that the music he loved [as a kid] was gone by the late-’60s and the Beatles were largely responsible for that.

“Obviously, in some way the title is inaccurate, because in some form rock ‘n’ roll is still around. But there were a couple of points I was trying to make. One was any shift in music produces winners and losers, but some stories always get told the same way. The Beatles’ story always gets told as them starting as a fun band and developing into this greater, artistically more mature thing. I don’t disagree with that, but there’s an equal way of telling it. They started out playing mainstream pop and simply abandoned what had been their core constituency.”

♦ ♦ ♦

Watch Dylan perform “Maggie’s Form” at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival

[Spoiler Alert: Following the theatrical release of the 2024 biopic, A Complete Unknown, Wald shared his thoughts on the topic of the audience booing Dylan at Newport. “There is clear evidence that some people booed Dylan’s first electric song, ‘Maggie’s Farm,’ but none of that booing was caught on tape. The amplifiers onstage were so loud that the microphones were turned way down, and no crowd noise is audible until the band left the stage — at which point the mikes were turned back up and captured a cacophony of booing, cheering, and demands for Dylan to come back. I quote a bunch of the audible shouts in Dylan Goes Electric! but, again, those are just the few that happened to be preserved, and there is no way to know if they were typical or representative.”]

BCB: Did you reach out to Dylan’s camp to see if he wanted to talk about Newport? Not that he would, but….

Wald: Yes and no. There was stuff that Dylan’s camp had that I wanted and I decided the best way to approach Dylan’s camp was to approach them and say, “I don’t need to talk to Bob but here’s what I do want,” and their reaction was “You don’t need to talk to Bob? We’ll do anything for you.” They – his manager Jeff Rosen – were terrific. They were really good about the afternoon set Dylan did in ‘65, too. There are parts of that set, the version of “Tombstone Blues” that I talk about that had never surfaced even among the most crazy bootleggers and I’ve heard it.

BCB: Do you harbor any desire to hear back from Dylan about the book?

Wald: I hope so. That would be nice. Obviously, like anyone who writes about Dylan, I’m interested to know what he would think.

BCB: Any feedback yet from the vast network of Dylanophiles?

Wald: What the vast network of Dylanophiles has told me so far is of the couple of errors that I’ve made and I’m sure they’ll pick out more. The great advantage of writing about Dylan is you have this army of fact-checkers out there.

BCB: What’s your greatest whopper?

Wald: For example, his Forest Hills concert – somehow I wrote that he did it on August 20 rather than August 28. And I have it [the correct date] written in my notes. Within seconds, someone spotted that one.

BCB: Any more egregious errors?

Wald: No. There are going to be some people who are going to be peevish about the fact that this isn’t a book about Dylan the poet and there are people who feel like that’s the only story. But it’s not the story I’m telling. So far the reaction of Dylan people I’ve talked to has been, “Hey, it’s really neat to have a different perspective,” and, “I’ve read so many goddamn Dylan books I didn’t know why I needed to read another, and it’s cool that there’s actually another perspective.”

BCB: So, how many times have you seen Dylan live?

Wald: (Laughs) Twice. I haven’t seen Dylan in 40 years. I saw him on tour with the Band [in 1974] and with the Rolling Thunder Revue [in 1975]. I walked out saying that’s the greatest concert I’ve ever seen in my life, but I was honestly more blown away by Mick Ronson than by Dylan, but there you go. The Dylan/Band tour, he was magical in a way he was not on Rolling Thunder. It was Boston Garden and he must have been the size of a toothpick. But it was magical.

Wald’s book is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- 10 Songs That Defined New Wave Music - 07/01/2025

- Mark Farner Interview: Grand Funk Railroad’s Legacy - 06/05/2025

- ‘1971’ Book Makes a Strong Case for Best Rock Year - 04/11/2025

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI was there. He was boo’ed with passion by a very significant percentage of audience. To idiots that listen to tapes – it’s ridiculous to think a microphone and the human ear respond the same way to sound pressure close and distant. Microphones respond much more to closer proximity.

Quite true. I appreciate you making the audience/nearness of microphone distinction (depending on where audience members sat). The fact that there was booing at all would have been a new phenomenon at a Dylan performance. After that, not so much.