The Marketing of Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Darkness On the Edge of Town’: The Inside Story

by Greg Brodsky

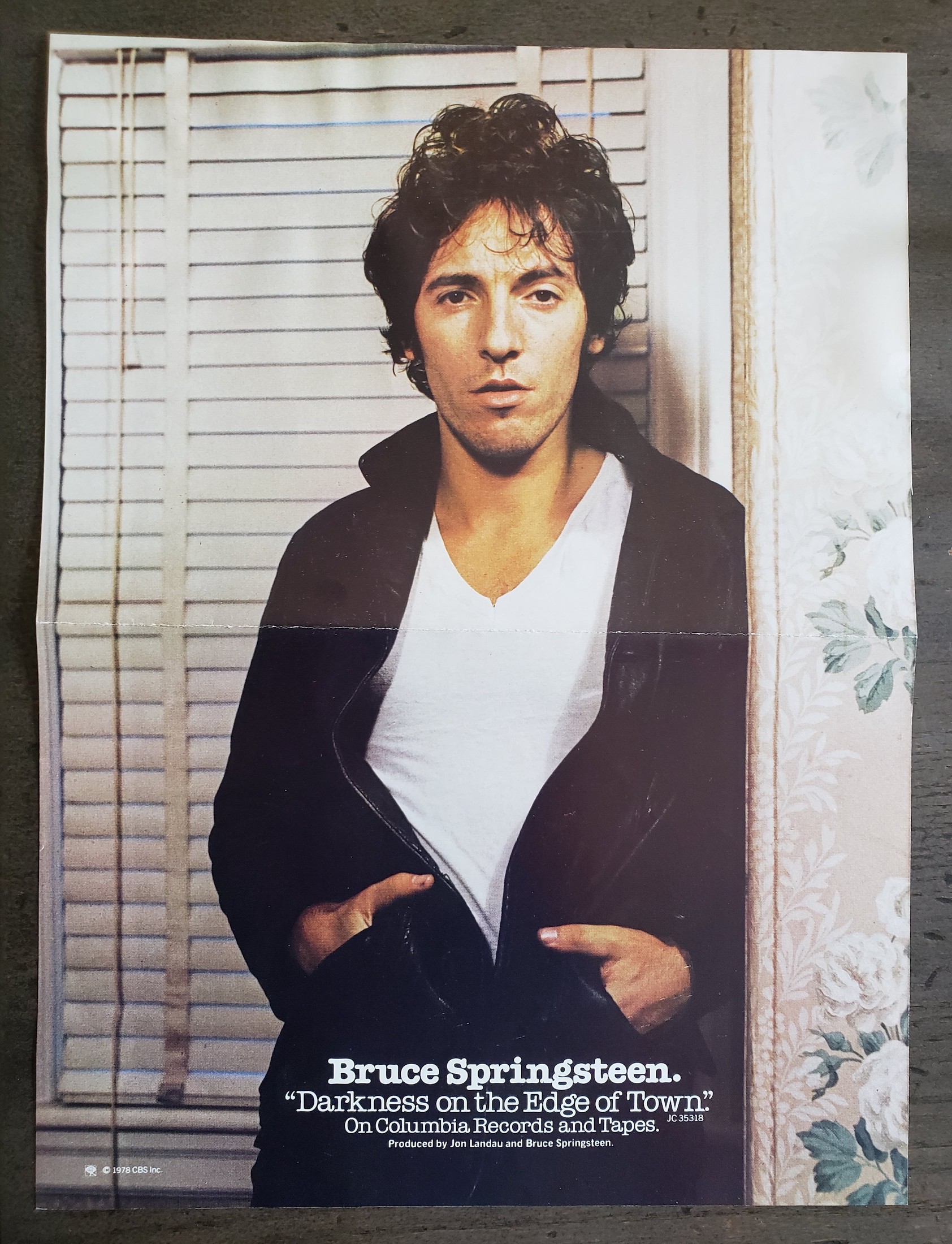

This ad for Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness On the Edge of Town appeared in Billboard in June 1978

Before Dick Wingate started college in 1970, he had already seen the Beach Boys perform when he was 13, the Young Rascals when he was 14, the Doors when he was 15, Cream when he was 16, Jeff Beck with Rod Stewart when he was 17 and the Stones when he was 18. Such was his good fortune to be growing up near New Haven, Conn., as a fanatic of the local Top 40 station when the format played rock acts, and within close proximity to New York City. By his Junior year at Brown University, Wingate was the Music Director for the school’s dynamic radio station, WBRU-FM. At the time, the station was so prominent in Rhode Island—with ratings nearly as high as the leading Top 40 station—that record label execs in New York and their staffers in the Boston field offices would pay far more attention to ‘BRU than a college station ought to reasonably expect.

Such was the case in early 1973 when Columbia Records brought their newest artist, 23-year-old Bruce Springsteen, to the station. WBRU had been one of the first stations in the entire country to play his debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, and the label brought him by for an informal meet-and-greet with the station’s student officers. “He was really shy,” Wingate recalls. “It was his first or second time at a radio station.”

One year later, on April 26, 1974, Springsteen and the E Street Band played Brown’s spring weekend. “It started with a solo spotlight on Suki Lahav—the Israeli-born violin player and wife of Louie Lahav, who engineered the first album—during ‘New York City Serenade’ and already I thought, ‘Wow,'” says Wingate. “I had never seen anything like that to start a rock and roll concert. I think he played for an hour and forty minutes and I was just blown away. Like nothing I had ever seen before. I had never seen a performer like that. I had seen Jagger and the Stones in ’69 at Madison Square Garden. And I had seen the Doors in ’67. I had seen Pink Floyd. The Allman Brothers Band. But here was this new artist who was mindblowingly great and I became a fanatic.”

Watch Springsteen and the E Street Band perform in 1973

Wingate soon graduated and got his first job in the record industry with Chess/Janus Records doing radio promotion for the progressive rock acts on the label, as well as a Muddy Waters record. He also started going to a lot of Springsteen shows throughout 1974 and 1975. “In my head, though, I wanted to work for Columbia. Springsteen was just one of the reasons… Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, Santana, you name it. I had already made lots and lots of friends there. I remember sitting in Glen Brunman’s office—he was Bruce’s publicist at Columbia—listening to the Born To Run album. It went so far beyond the first two albums, so operatic, so dramatic.

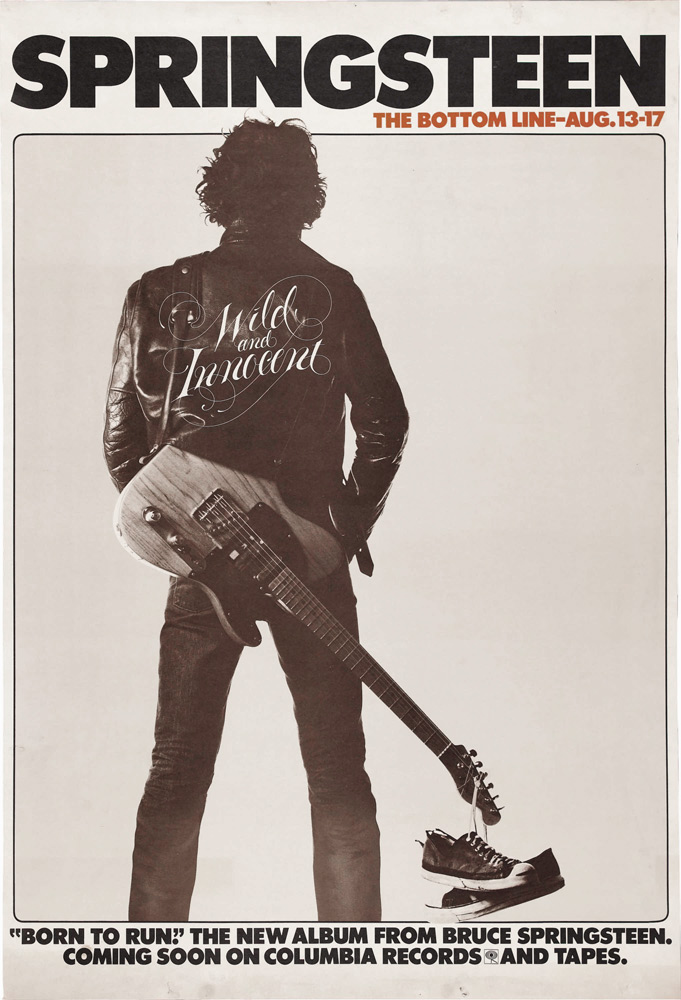

“When he played the Bottom Line—the famous 10 shows in five nights in August 1975—I was at four of the shows. One of them, I only had tickets for the first show and was so desperate to see the second show that I hid in the bathroom until they turned the house and got to see two shows that night.”

“When he played the Bottom Line—the famous 10 shows in five nights in August 1975—I was at four of the shows. One of them, I only had tickets for the first show and was so desperate to see the second show that I hid in the bathroom until they turned the house and got to see two shows that night.”

Much to his joy, he got a call from Columbia to interview for an open product manager position at the label’s HQ in midtown Manhattan. “When I went into the interview to close the deal, I asked if there was any way I could work with Bruce Springsteen. As luck would have it, his product manager was moving up to a more managerial position and I was able to have Bruce as one of my assigned artists.”

Springsteen was roughly two-and-a-half years older than Wingate. “I think that was one of the reasons I was handed ‘the account.’ I was closer to his age and I had met him. I was clearly a fan and had probably seen him ten times even before I went to work for Columbia.”

Wingate began on the tail end of the Born To Run tour, in early 1976. The label was supporting the dates with local marketing efforts but because of the ongoing lawsuit involving his former manager/producer Mike Appel, there was no new record for a lengthy period. Wingate used that time to develop a relationship with Springsteen’s soon-to-be manager and producer, Jon Landau, and would see Bruce occasionally on the road during the “Chicken Scratch” tour as it became known.

After the lawsuit was finally settled, one time during the recording of Darkness, “I took Bruce and Steve Van Zandt to a Yankee game with my good friend, Michael Pillot, who was Columbia’s head of album promotion. Bruce had recently shaved and nobody recognized him! We took the subway, went to the Yankee game, and took the subway back, and I think he was recognized by all of two or three people the entire time. Born To Run was already two years old. He didn’t have the beard, the earring, and wasn’t wearing sneakers anymore. His image was changing.”

In early 1978, “I finally was able to hear Darkness on the Edge of Town for the first time when I was asked to go to the Record Plant [studio] for a playback. There was only one other person who was invited… Mickey Eichner, Columbia’s head of East Coast A&R. And we sat with Jimmy Iovine [who engineered the album] and Jon Landau and I was thrilled, not only because I was chosen to hear it up front, but because I knew that this was not Born To Run part two. It was a tough-as-nails album! It was a more sophisticated album, which spoke to what was going on in the world at the time. It was my challenge to start to educate the rest of the company as to what was coming and what to expect.”

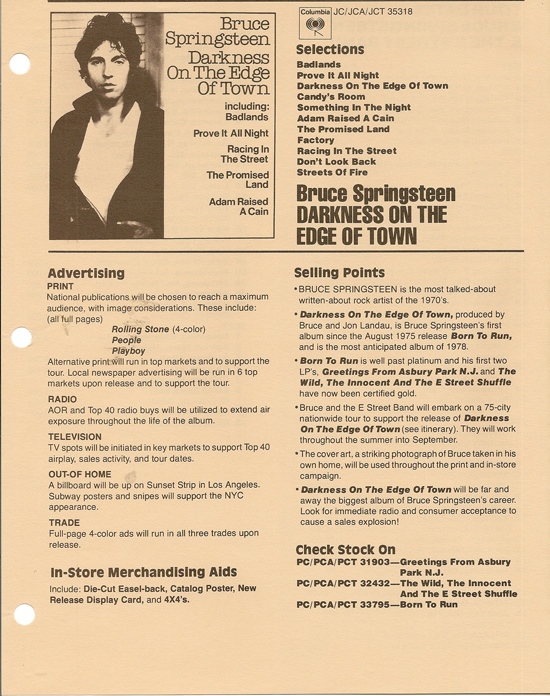

The solicitation sheet that the CBS Records distribution team used to sell-in the album to retailers (Photo: Dick Wingate archives)

Wingate’s pivotal meeting with Springsteen in his role as his product manager took place in early spring of ’78, when he flew to L.A. to meet with the recording artist, who was there mastering the album. “I had to talk to him about what we were going to be doing in terms of marketing and positioning. I had already received a lengthy, two-page letter from his lawyer which outlined how Bruce had to approve basically everything. Nothing was to be released without his approval. He was unhappy with some of the Born To Run merchandising materials. He had famously torn down posters in London before his first show at the Hammersmith. There were posters all over town and he hated the hype. He never wanted to hear ‘the future of rock and roll’ again. He just wanted his music to stand on its own terms.

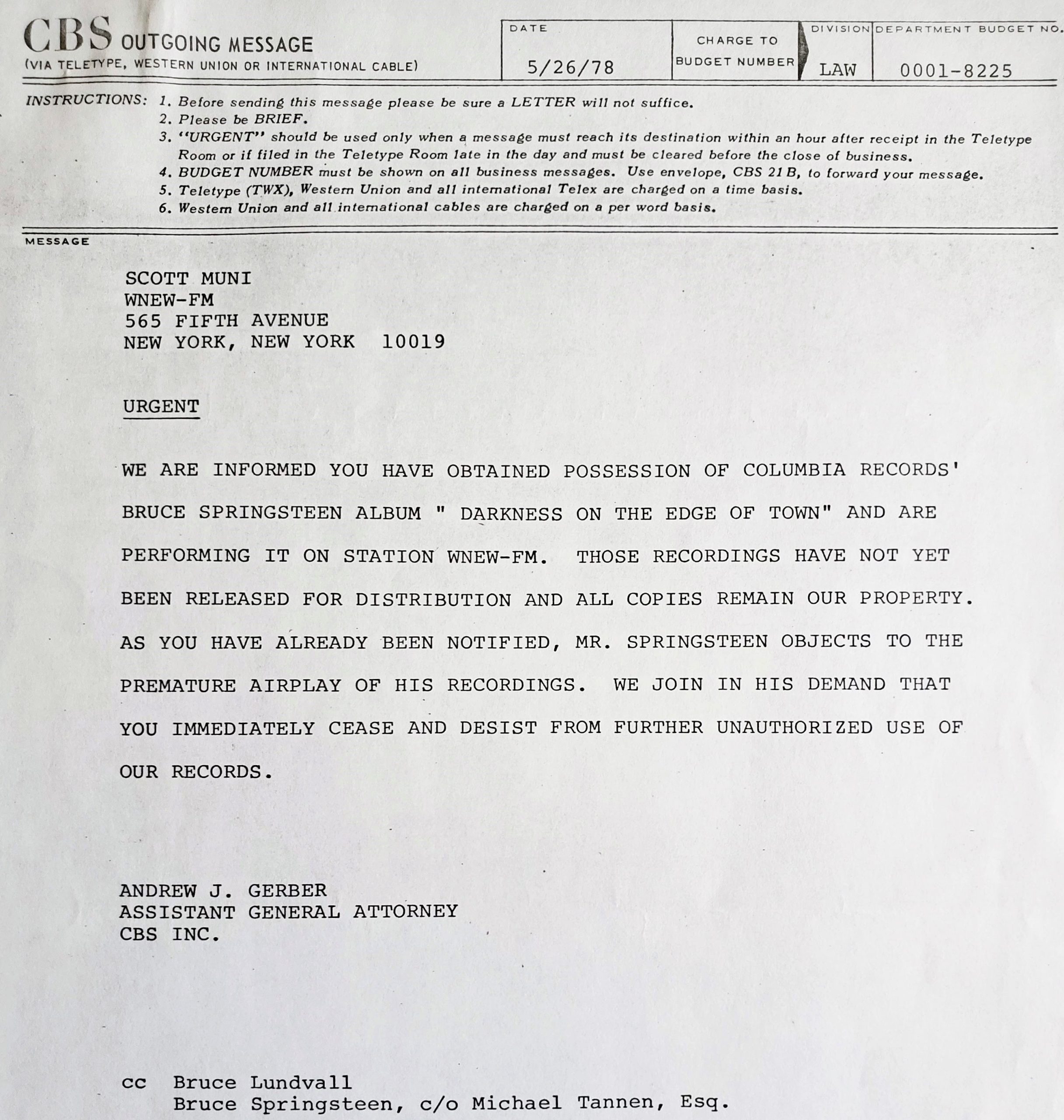

“So I sat with him at a burger joint on Sunset, and he said, ‘Dick, if it were up to me, I’d like this album to just appear in the stores one day. No advance hype.’ I said, ‘Bruce, if you want to have any records in the store, we have to promote sell-in to the retailers. That’s number one. Number two, we have to get radio prepared.'” For big stars, that sometimes also meant having to temper the stations’ enthusiasm for playing records too early, by sending a cease-and-desist telegram like the one shown here that was sent to New York’s WNEW-FM.

A cease-and-desist telegram that was sent to New York’s WNEW-FM (Photo: Dick Wingate archives)

“By the time I left L.A., Bruce decided he wanted to make some changes and was going to go back to New York to put Stevie’s guitar solo back into ‘Promised Land.’ [“Don’t Look Back” also came off the album at the last minute.]

Still, Springsteen made it very clear: no old photographs, no sneakers, no shots with beards. “Basically, throw all that stuff away. We did great, new photo shoots. And the cover turned out to be one of Frank Stefanko’s, taken in Frank’s house. Bruce showed up with a paper bag and a couple of shirts and jackets. It was completely natural.

“All of the advertising that we did—this is what I promised him at that lunch—simply: “Bruce Springsteen… The new album, ‘Darkness On the Edge of Town’, and the release date. Same with the TV spot we ran on SNL. Can’t have any less information than that.”

Now when an album cover is done, typically the proof is shown to the artist and/or manager to sign off, and off it goes to be printed. “But Landau called me one day and said Bruce wanted to go to the printer and actually approve it coming off the machines,” Wingate recalls.

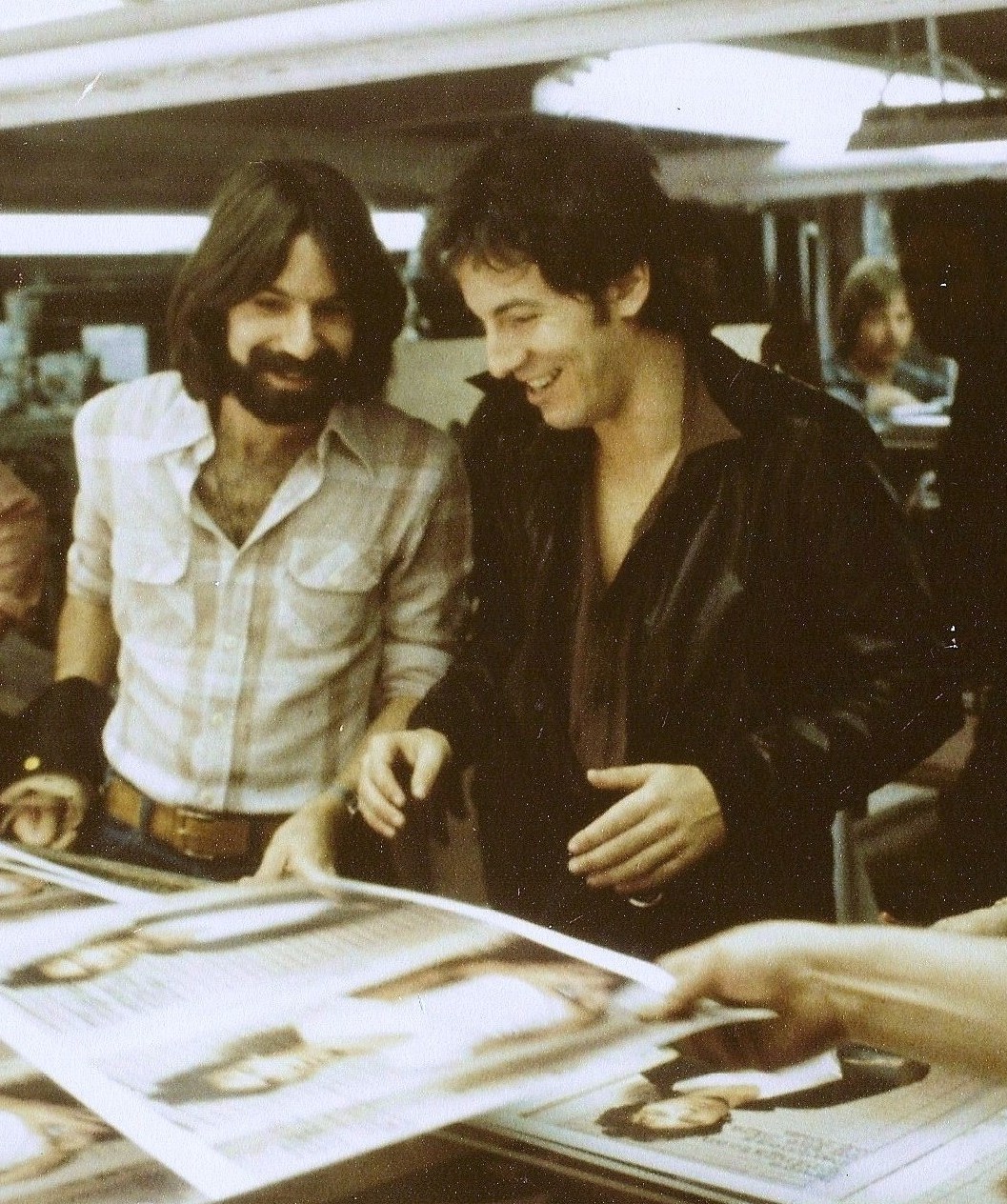

It was the first time in CBS Records history that an artist came to the plant on the day-of, in this case Ivy Hill Lithograph. “You can see from the photograph that Bruce is very happy. He’s seen the first run of album covers.”

Dick Wingate and Bruce Springsteen at Ivy Hill Lithograph in 1978 (Photo: Dick Wingate archives via Doug Yule)

Wingate is asked how that photo came about. “A guy comes up to me and he says, ‘Do you mind if I take a couple of pictures?’ I said, ‘Sure, write down your name.’ He scratches his name, Doug Yule, and his phone number. And I’m looking at the card and I say, ‘Are you the Doug Yule that was in the Velvet Underground?'” It was, indeed.

Darkness was released on June 2, 1978. Besides the trade advertising, print ads and radio spots, a vital component of the Darkness marketing plan was syndicated regional broadcasts on top rock stations throughout the ’78 tour. “We did legendary ones that are now widely available from Los Angeles, New York, Cleveland, Atlanta and San Francisco.

“Then six weeks into the tour, we made the video.”

Wingate went to Phoenix in July with Arnold Levine, Columbia’s in-house video director, to shoot five songs, three from Darkness, plus “Born To Run” and “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight).” “The only one Bruce agreed to release was ‘Rosalita,’ which was two albums old! But it was incredible because by the time [the E Street Band] got to ‘Rosalita’ he was no longer paying attention to the cameras, the band was hot. These girls rushed on to the stage and everyone thinks that was staged and it wasn’t.”

“That video became the way people all over the world learned about Bruce Springsteen. The performance in that video was so fantastic that it made everyone want to come and see the show.” Prior to that, Bruce hadn’t played anywhere [outside of North America] except for the London show. It was essential even within the CBS Records family to get everyone to understand the power of the E Street Band!”

Surprisingly, given the success of its predecessor, his relentless tour schedule and the excitement of a new album after such a long interval, Darkness didn’t hit #1. The biggest competition in the summer of ’78 were the Saturday Night Fever and Grease soundtracks, 20-year-old budding pop superstar Andy Gibb, giant rock releases from the Rolling Stones (Some Girls), Bob Seger (Stranger in Town), Foreigner (Double Vision) and others.

“It was a good year for rock,” says Wingate. “Progressive rock was starting to fade just a bit and straight-ahead rock was ascending [again]. “Prove It All Night,” “Badlands” and “The Promised Land” were critical album radio tracks. And they absolutely are in every Springsteen show. You can debate what’s his best album but the songs that get played in the majority of Springsteen shows are from Darkness and Born To Run.”

Related: Our recap of the April 1, 2023 concert at New York’s Madison Square Garden

CBS Records had a designated billboard on the Sunset Strip at the time and the label group would use the space for its biggest stars. “The Darkness album cover didn’t lend itself to a horizontal layout but [the company posted one anyway]. It was garish-looking and Bruce hated it. One night when the band was in L.A. they literally went out in the middle of the night with cans of paint and climbed up and did their thing! It’s a classic [story]. And that only brought more attention to it!”

The Darkness billboard on the Sunset Strip (Photo: Dick Wingate archives)

Toward the end of ’78, Wingate got an offer to join Columbia’s sister label Epic Records, in A&R. The company got incredibly hot—with such successes as Michael Jackson, the Clash, Cyndi Lauper, Boston, Culture Club, REO Speedwagon and Stevie Ray Vaughan—and starting to become the equal of Columbia. In the final weeks of his tenure at Columbia, Wingate went to Springsteen’s San Francisco show at Winterland only weeks before it closed.

“It was one of the greatest shows of the 25 that I saw between June and December. After the show, Bill Graham had a party which went way into the night at his house in the San Francisco hills and I told Bruce that I was moving on and he couldn’t have been more supportive. It was important for me to have his good wishes as I moved on.”

The album was released on June 2, 1978, and ultimately peaked on the Billboard album chart at #5. It’s been certified 3x Platinum, fitting in between such studio juggernauts as Born In the U.S.A. (17x) and Born To Run (7x), and ahead of another classic, The Rising.

Tickets to see Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band are available here. His recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

On June 2, 2023, the 45th anniversary of the album’s release, the Springsteen team shared a new 20-song live playlist from the ’78 tour. Listen to it on Spotify.

At Epic, Wingate‘s signings included Aimee Mann’s ‘Til Tuesday (Voices Carry), Eddy Grant (Electric Avenue), Stiff Records and Garland Jeffreys. He subsequently held senior executive roles as SVP A&R at PolyGram and SVP Marketing at Arista Records. He later helped pioneer the digital music business at Liquid Audio, negotiating the first digital licensing deals with nearly every label. His digital entertainment consulting firm, DEV Advisors, provides expertise to content owners, artists, service providers, app developers and investors.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI was 16 when this came out. We were the 70s street kids, the “armies of the night.” We were the party animals who ruled the nights running the roads in our muscle cars. No statement could be more true and I don’t see this era ever repeating.

The “Born to Run” album had been our road map. The Boss was our spokesman from the heavens. We awaited “volume 2.” We needed more “Jungleland.” We missed the Magic Rat.

Two teasers played across the Central NY region, “Darkness” and “Prove it All Night.” We were in line to get the album on release day, expecting BTR II. It wasn’t that.

The adrenaline rush was gone. We liked the album, but it wasn’t what we were looking for, we thought… This was the era of the cassette. Someone thought to make a tape of it and a new life emerged! This became our dashboard poetry. Listened to in any car, it took on a new life, a new energy and we embraced it and our lives merged with it.

When gathering, “Racing in the Street.” became the only anthem that we would sing along with collectively. (We weren’t “sing along” kind of people). The melancholy of the message moved us so deeply that we felt we could sing it in unison.

We grew to know every word, every nuance, of every song on the album.We felt Bruce knew us and what we were experiencing.

This album held a special place not just for me, but for anyone who ever revved up an engine, squealed their tires and burned off into the night. I’m loading the cd now. At 60, I wish I could go back again. (Or maybe I just did).