Why Bob Dylan Covered the Rick Nelson Hit ‘Garden Party’

by Jeff Tamarkin

When Bob Dylan covered Rick Nelson’s 1972 hit “Garden Party” at his May 15, 2025, performance in Chula Vista, Calif.—his encore at Willie Nelson’s (no relation) 10th anniversary Outlaw Music Festival—some veteran Dylan watchers (yes, there are still many who chart his every move) expressed surprise in social media posts. They shouldn’t have been so astonished: Although Dylan had never performed the song before, there was nothing out of character about him doing so, due both to the song’s lyrical content and the fact that he and Rick Nelson, who died in a plane crash on the last day of 1985 at age 45, had long admired, and paid tribute to, one another.

Dylan has been a fan of Nelson’s since they were both teens (Nelson—inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, among its second class—was just a year older). “I’d always felt kin to him,” wrote Dylan in his memoir, Chronicles: Volume One. “We were about the same age, probably liked the same things, from the same generation although our life experience had been so dissimilar…It was like he’d been born and raised on Walden Pond where everything was hunky-dory, and I’d come out of the dark demonic woods, same forest, just a different way of looking at things.”

Perhaps some Dylan acolytes might find his admiration of Nelson surprising in itself. Rick (originally Ricky) Nelson—who’d initially found fame as a co-star on a family TV show, before he’d ever made a record—was the least wild, most wholesome and parent-friendly of the early rockers: Little Richard or Jerry Lee Lewis he wasn’t. But neither was he a manufactured, gloopy no-talent whose value as a pinup boy outweighed his genuine gifts as a musical artist: Nelson’s brand of rock ’n’ roll in his earliest years was come by honestly; not raw but inherently, inarguably soulful. Comparing him to the more outlandish personalities of the era is neither necessary nor fair; what Nelson offered was just as valid, and just as enduring.

“[Nelson] had never been a bold innovator like the early singers who sang like they were navigating burning ships,” was how Dylan put it in Chronicles. “He didn’t sing desperately, do a lot of damage, and you’d never mistake him for a shaman…He sang his songs calm and steady, like he was in the middle of a storm, men hurling past him. His voice was sort of mysterious and made you fall into a certain mood.”

Dylan knew real from phony. We’re used to hearing him praise the earthier, gutsier blues and folk artists, and the rougher, more threatening rock ’n’ roll that shook the planet during his own formative years, but he understood Ricky Nelson’s smoother, more mainstream delivery as well. Others might consider Nelson, with his Hollywood upbringing and clean-cut demeanor, a lightweight, someone who would not move the likes of Bob Dylan. But Dylan considered Nelson one of his early rock heroes, and still did when he covered Nelson’s haunting, ethereal 1958 Top 10 ballad “Lonesome Town” in concert no fewer than 56 times between 1986 and ’89, often with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in tow.

Nelson, for his part, was an unabashed Dylan disciple. His last chart hit of the ’60s, and first with his visionary country-rock outfit the Stone Canyon Band—the very band that backed him at the concert that instigated “Garden Party”—was Dylan’s “She Belongs to Me,” which peaked at #33. He also covered Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” and “I Shall Be Released.”

In a promotional film, Nelson said, “My idol as far as a writer is Bob Dylan, who I think was really the spokesman for that period…I really tried to emulate Bob Dylan as a songwriter.”

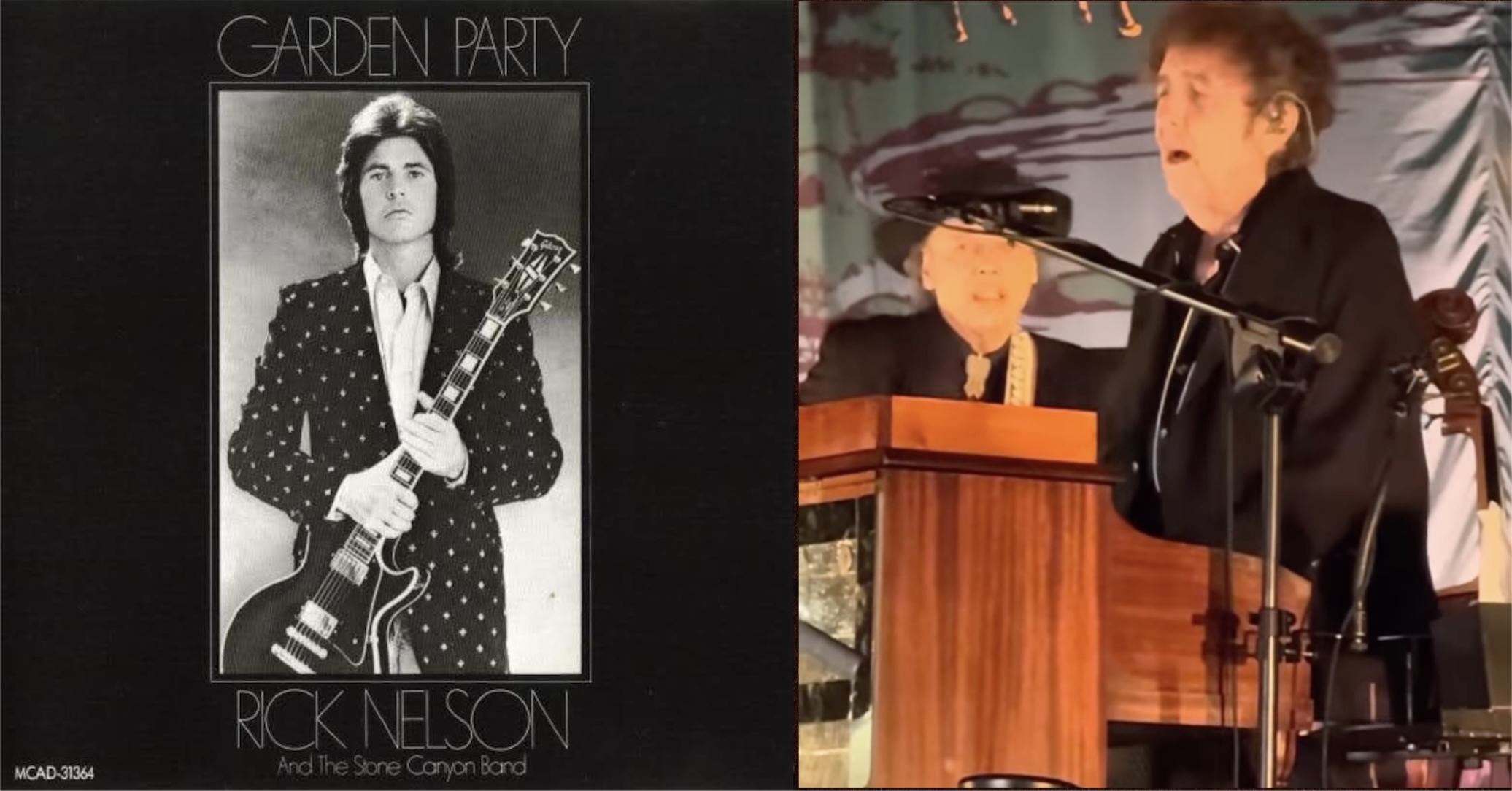

Although Nelson did not write most of his songs, he did write “Garden Party,” and it is, for Dylan, a smart, and not wholly unexpected, cover choice. If anything, what might be most surprising is that his rendition was so faithful to the original, Nelson’s last Top 40 hit. Dylan did not trick out “Garden Party”; he played it straight, the way Nelson wrote it and recorded it more than 50 years ago. There was nothing in the Chula Vista performance, which took place at the North Island Credit Union Amphitheatre, that would throw off a listener—at least one who already knew the song.

Although Nelson did not write most of his songs, he did write “Garden Party,” and it is, for Dylan, a smart, and not wholly unexpected, cover choice. If anything, what might be most surprising is that his rendition was so faithful to the original, Nelson’s last Top 40 hit. Dylan did not trick out “Garden Party”; he played it straight, the way Nelson wrote it and recorded it more than 50 years ago. There was nothing in the Chula Vista performance, which took place at the North Island Credit Union Amphitheatre, that would throw off a listener—at least one who already knew the song.

For Dylan, that’s a big deal, a conscious decision to respect what Nelson had to say and the way he said it. Dylan’s career as a stage performer has, pretty much since the beginning, been marked by drastically rearranged—some might say reinvented—versions of his own material, often to the point that even the most seasoned fans don’t always know what song he’s playing until he’s well into it. When he does interpret a song by another composer, it’s nearly always customized—Dylanized—to suit his whims at that moment.

Related: Whatever became of Rick Nelson’s singing twin sons, Gunnar and Matthew?

Even today, as an elder with more than six decades of performing experience behind him—Dylan turned 84 on May 24, 2025—when he reprises a song from his vast catalog, there is virtually no chance that he will present it as it was first heard on record. For him, a song is a living, breathing, ever-evolving organism. If a fan should walk away disappointed from one of his concerts because he didn’t play his “hits”—and play them exactly the way he did on the original recording—that’s on them, not him.

Check out this retooled “All Along the Watchtower” from the same tour for just one of thousands of examples.

And how about his take on “The Night We Called it a Day,” written in 1941 and one of many Great American Songbook numbers with which Dylan filled several albums in the 20-teens? Who, when listening to Highway 61 Revisited in 1965, could have imagined him, a half-century later on an album called Shadows in the Night, consisting entirely of tunes associated with Frank Sinatra, sounding like this?

Dylan has always gone his own way, and a line in the chorus of “Garden Party”—“You can’t please everyone, so you gotta please yourself”— sums up his attitude toward his entire career. Instead of being startled, perhaps Dylanologists should have wondered when he would finally get around to it. When he did, he apparently decided that the song didn’t require personalization; it was just fine the way Nelson made it.

Clockwise from bottom: Ozzie, Harriet, David, Ricky in 1952.

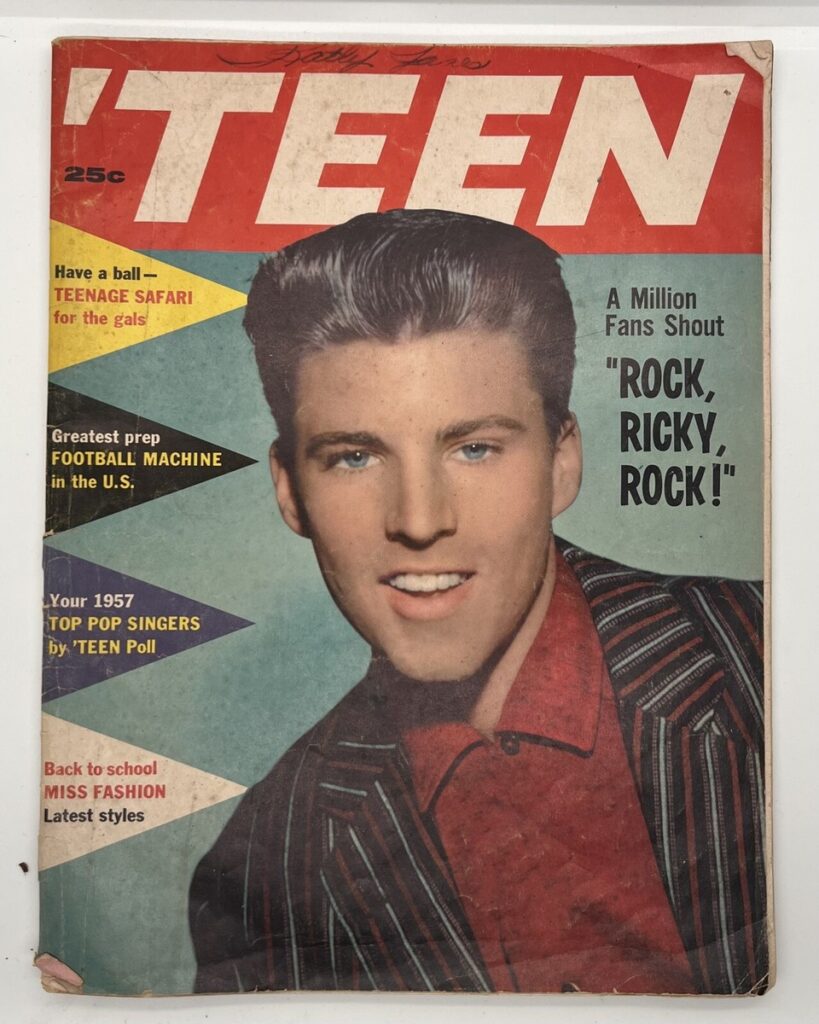

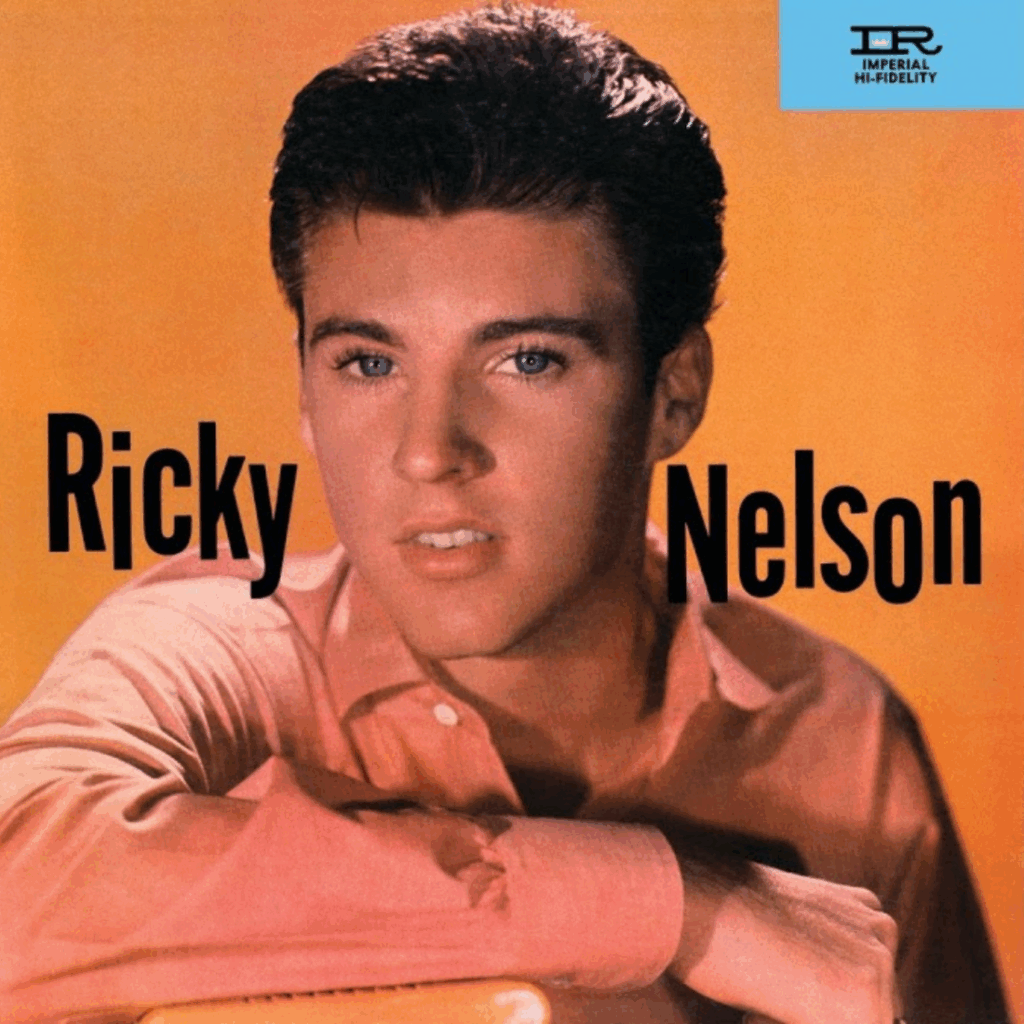

Perhaps a bit more context is a good idea. Even before he was known as a singer, Rick Nelson was an actor, and a very famous one at that—a teen idol of the highest order. Born in Teaneck, N.J., on May 8, 1940, Eric Hilliard Nelson was the younger of two sons born to actor and bandleader Ozzie Nelson and actress and singer Harriet Nelson. Ricky arrived about three-and-a-half years after brother David Nelson, and the family relocated to Hollywood when both were still kids. The radio program The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet debuted in 1944, with David and Ricky joining them on the show in 1949. In 1952, it moved to television, the medium just picking up steam at the time, and with each successive year the show became more successful. By his late teens, Ricky had amassed a sizable following, largely of teenage girls, and in March 1957, supposedly in order to impress his then-girlfriend, he recorded his first single, a cover of Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin’,” for the Verve label, which catapulted to #4 on the Billboard chart.

Ricky became an instant teen idol, one of the most beloved and successful singers of the late ’50s, all while continuing to act in the series helmed by his father. Photos of Ricky’s cherubic face adorned the walls of teen girls throughout the U.S. and they adored his music. He logged 11 further Top 10 hits—most of which featured his hand-chosen band, including ace guitarist James Burton—before the decade was out, among them “A Teenager’s Romance,” “Be-Bop Baby,” “Stood Up,” the #1 “Poor Little Fool” (about which Dylan wrote in his book The Philosophy of Modern Song) and the aforementioned “Lonesome Town.” Nelson also appeared in numerous films, among them the John Wayne Western Rio Bravo (1959), which also co-starred Dean Martin, Angie Dickinson and Walter Brennan.

Ricky became an instant teen idol, one of the most beloved and successful singers of the late ’50s, all while continuing to act in the series helmed by his father. Photos of Ricky’s cherubic face adorned the walls of teen girls throughout the U.S. and they adored his music. He logged 11 further Top 10 hits—most of which featured his hand-chosen band, including ace guitarist James Burton—before the decade was out, among them “A Teenager’s Romance,” “Be-Bop Baby,” “Stood Up,” the #1 “Poor Little Fool” (about which Dylan wrote in his book The Philosophy of Modern Song) and the aforementioned “Lonesome Town.” Nelson also appeared in numerous films, among them the John Wayne Western Rio Bravo (1959), which also co-starred Dean Martin, Angie Dickinson and Walter Brennan.

Although his string of hits, mostly for Imperial Records, then for Decca, calmed down as the ’60s kicked in, he still managed a second and final chart-topper, the double-sided smash “Travelin’ Man”/“Hello Mary Lou” in 1961, and a few more Top 10s before his mega-successful run dissipated slowly. By 1966, with the British Invasion having changed everything, Rick Nelson—the name shortening came in 1961—was yesterday’s news.

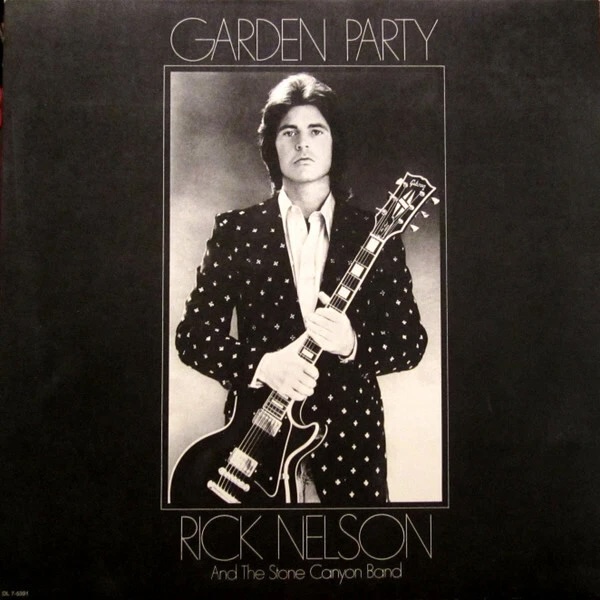

The Stone Canyon Band (Rick Nelson at center)

Despite that, he wasn’t finished making music. In 1966, he released the album Bright Lights and Country Music, which included contributions by guitarists Burton, Clarence White and Glen Campbell. Country Fever followed in ’67, and, in 1969—around the same time that bands like the Byrds, Poco and the Flying Burrito Brothers were also tying together rock and country—Nelson formed the Stone Canyon Band and cut the live album In Concert at the Troubadour, 1969, which charted at #54, his first LP to find its way into Billboard since 1963. (The album included three of the aforementioned Dylan tunes.)

It could hardly be considered a full-scale comeback, but the album did bring Nelson some much-needed new attention, with many critics noting the skillful band, which included, among other players, the bassist Randy Meisner, who would later go on to co-found a band that would do reasonably well under the name Eagles.

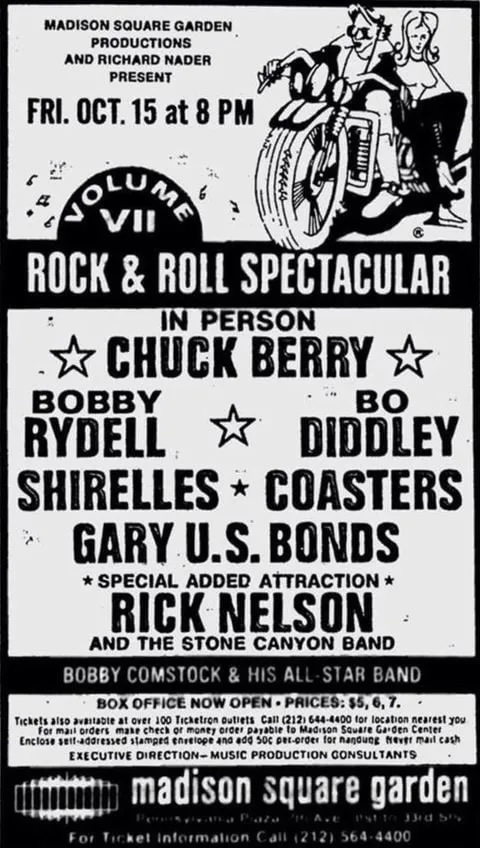

The live album proved something of a fluke though, and when, in 1971, he received an invitation from a New York City-based concert promoter named Richard Nader—then building an empire by staging “revival” shows that reunited long-gone early rock ’n’ roll and doo-wop groups and brought back stars of the past—to perform at Madison Square Garden, Nelson happily accepted. There, on Oct. 15, he and the Stone Canyon Band would serve as the “Special Added Attraction” on the Rock & Roll Spectacular Volume VII program, which also featured Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, the Shirelles, the Coasters, Bobby Rydell and Gary U.S. Bonds. Nelson, who by then sported period-appropriate long hair and dressed in the contemporary style (purple velvet shirt and bell bottoms!), having outgrown his boyish, all-American look of the ’50s and early ’60s, prepared a set that included some of his old hits but also songs from his then-current country-rock repertoire.

The live album proved something of a fluke though, and when, in 1971, he received an invitation from a New York City-based concert promoter named Richard Nader—then building an empire by staging “revival” shows that reunited long-gone early rock ’n’ roll and doo-wop groups and brought back stars of the past—to perform at Madison Square Garden, Nelson happily accepted. There, on Oct. 15, he and the Stone Canyon Band would serve as the “Special Added Attraction” on the Rock & Roll Spectacular Volume VII program, which also featured Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, the Shirelles, the Coasters, Bobby Rydell and Gary U.S. Bonds. Nelson, who by then sported period-appropriate long hair and dressed in the contemporary style (purple velvet shirt and bell bottoms!), having outgrown his boyish, all-American look of the ’50s and early ’60s, prepared a set that included some of his old hits but also songs from his then-current country-rock repertoire.

It didn’t go quite as he’d hoped. When Nelson launched into the Rolling Stones’ “Country Honk,” a country-ized retooling of their “Honky Tonk Women,” there was booing in the audience. They weren’t there to hear new songs, they wanted the oldies. A disgusted Rick Nelson bolted from the stage, returning to perform a few of his hits only when urged by the promoter. (Some attendees said that the booing was directed toward police who were making a ruckus in the venue.)

Nelson couldn’t get the experience out of his head. Why, he wondered, was it OK for artists like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Dylan to grow and change, but not him? Why did he have to remain tethered to his past?

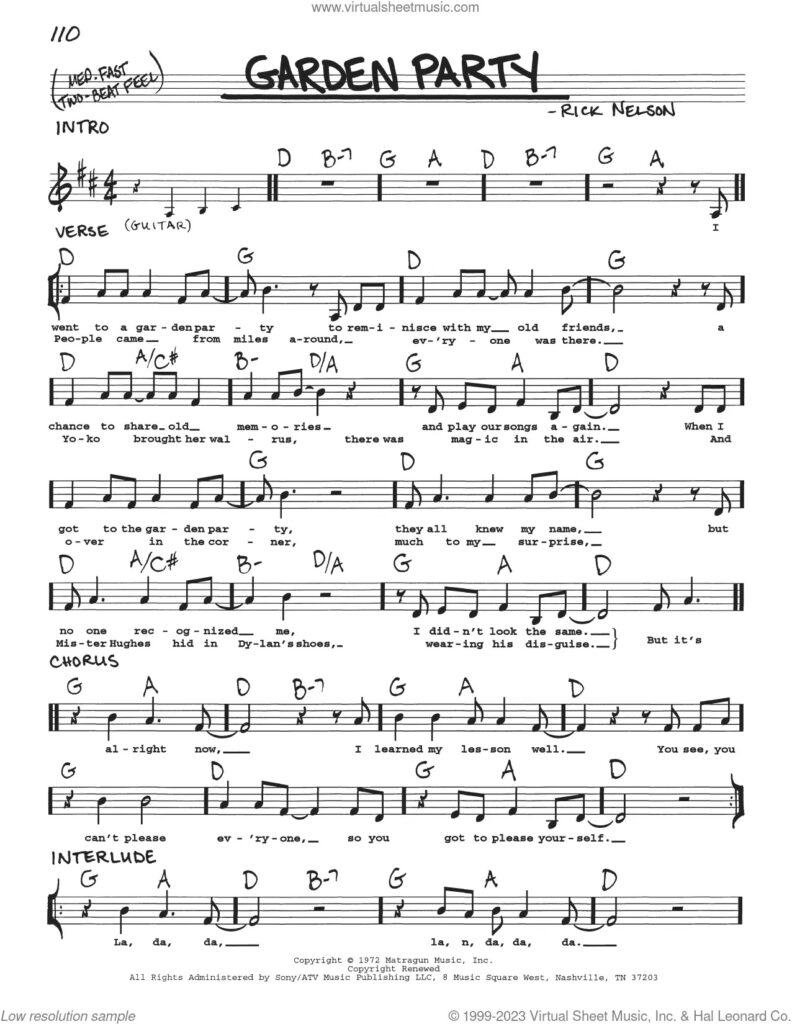

He started working on the song that would become “Garden Party”: “I went to a garden party to reminisce with my old friends,” it began, continuing with a rundown—sometimes straightforward, other times veiled—of what went down that night. There were references to Chuck Berry, who topped the bill, and to John Lennon and Yoko Ono, who were reportedly in the audience. Another verse was less clear: “And over in the corner, much to my surprise, Mr. Hughes hid in Dylan’s shoes, wearing his disguise.”

He started working on the song that would become “Garden Party”: “I went to a garden party to reminisce with my old friends,” it began, continuing with a rundown—sometimes straightforward, other times veiled—of what went down that night. There were references to Chuck Berry, who topped the bill, and to John Lennon and Yoko Ono, who were reportedly in the audience. Another verse was less clear: “And over in the corner, much to my surprise, Mr. Hughes hid in Dylan’s shoes, wearing his disguise.”

Who was “Mr. Hughes”? Was it Dylan? The artist himself has never claimed that he attended the show and, although he was not spending much time in the limelight in 1971 (outside of a high-profile appearance at George Harrison’s Concert for Bangla Desh), he wasn’t wearing a disguise when he took in the Stones’ show at the same venue the following summer. Most analyses of the lyrics point to George Harrison, who supposedly registered in hotels under the pseudonym Mr. Hughes in order to skirt the attention of fans, suggesting he was reclusive like the eccentric, mega-wealthy business magnate Howard Hughes. Did Harrison, who was reportedly Nelson’s next-door neighbor at the time, sneak into the show wearing a disguise? That’s never been established either, although it’s been suggested that Harrison was, at the time, planning an album of Dylan covers that never materialized, which would explain the “Dylan’s shoes” reference. The song ended with a defiant bit of the bitter: “If you gotta play at garden parties, I wish you a lotta luck,” went the final verse, “but if memories were all I sang, I’d rather drive a truck.”

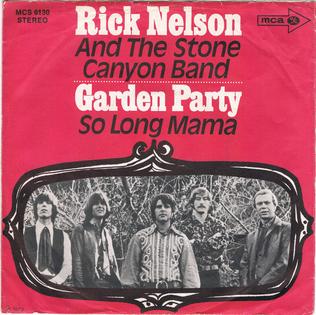

Regardless, “Garden Party,” with its telling chorus—“But it’s all right now/I learned my lesson well/You see, you can’t please everyone, so you gotta please yourself”—gave Rick Nelson his next single in the summer of 1972 and the title track for his next album. The single, set to an easygoing country-folk melody, caught on, peaking at #6 in the Billboard Hot 100, while the Garden Party album topped out at #32, Nelson’s highest placement there since 1964.

Regardless, “Garden Party,” with its telling chorus—“But it’s all right now/I learned my lesson well/You see, you can’t please everyone, so you gotta please yourself”—gave Rick Nelson his next single in the summer of 1972 and the title track for his next album. The single, set to an easygoing country-folk melody, caught on, peaking at #6 in the Billboard Hot 100, while the Garden Party album topped out at #32, Nelson’s highest placement there since 1964.

In the aftermath of the Madison Square Garden debacle and the resultant hit records, Rick Nelson again faded from the pop/rock spotlight, never again to score a hit album and placing just one more single onto the charts, for a career total of 63. In 1981, he released an underrated album for Capitol, Playing to Win, and toured on it, but it didn’t sell; his time as a hitmaker was now firmly behind him. His early hit singles continued to find respect as the years progressed though, even after the unfortunate plane crash that took Nelson’s life in DeKalb, Tex., on New Year’s Eve 1985, and other artists continued to praise him: Two years later, John Fogerty, who considered Nelson an influence—and who covered “Garden Party” on his 2009 The Blue Ridge Rangers Rides Again album, accompanied by Eagles’ Don Henley and Timothy B. Schmit—inducted Nelson into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, alongside such giants as Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, Roy Orbison and B.B. King.

Why, some 40 years after Nelson’s death, did Bob Dylan choose to perform “Garden Party”? Only Dylan knows, but one could certainly surmise. At its core, “Garden Party” is a protest song, a subgenre which Dylan virtually defined early in his career, although he hasn’t revisited it too often since. But more likely is that Dylan has always loved a good story song, and “Garden Party” certainly is that. Like “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” “Desolation Row,” “Tangled Up in Blue,” “Hurricane” and “I Contain Multitudes” from his most recent studio collection, 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways, the Nelson-authored “Garden Party” lays out a narrative, one that takes in tragedy and triumph, and makes a point with its key “You can’t please everyone, so you gotta please yourself” line. That’s the kind of song that Dylan savors.

Many have tried to tell Bob Dylan what to do and how to do it over the years, and he’s steadfastly told them where to go. He sings the songs he wants to sing, the way he wants to sing them, pleasing himself as best he can and shrugging off all concerns about what others—his fans included—might think.

There’s no indication that Dylan and Rick Nelson ever met or even conversed. But one likes to think that if they did, they’d have plenty of stories to share.

Watch Rick Nelson sing “Garden Party”

Nelson’s recording is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

A new collection focusing on covers of classic early Dylan songs, is being released by the Strawberry imprint of Cherry Red Records. I Shall Be Released: Covers of Bob Dylan 1963-1970 arrives July 25, 2025. The 3-CD set of 63 tracks is available for pre-order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationBob covered ‘Lonesome Town’ with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers. At one of the the three Madison Square Garden shows, Bob noted he was standing on the same stage where the events that inspired ‘Garden Party’ in his introduction to ‘Lonesome Town’.

Ricky had a unique delivery, a soulful voice – you just wanted to listen to him.

Thank you Jeff, you’ve always been respectful in your writings about Rick Nelson. I still have the Goldmine issue featuring your tribute to Rick after his passing.

Thank you! I’ve enjoyed listening to Rick since I first heard “Travelin’ Man.”