Color-Coded Love: A Bounty of Affection for the Beatles’ ‘Red Album’

by Colin Fleming Falling in love with a musical act may take many forms. Love always requires a choice to go deeper, if it is truly love, but first the heart must be alerted that here could be something worthy of affection and devotion. That opening chord doubles as estimable tip-off, for it’s a hell of a chord.

Falling in love with a musical act may take many forms. Love always requires a choice to go deeper, if it is truly love, but first the heart must be alerted that here could be something worthy of affection and devotion. That opening chord doubles as estimable tip-off, for it’s a hell of a chord.

With music, that opening chord, as such, can be a song you hear precisely when you need to hear it at a stage in your life. A day when you need to hear it. (Or the actual concluding chord of “A Day in the Life,” for that matter.)

There may be a personal, emotional attachment. A friend loans you a record and the entirety of its 40 minutes hits every last part of you in a manner that you sit there playing the thing again and again, unsure of how many official times it’s been.

To fall in love with a piece of music is a form of romance. We never forget our first loves, either, whether it was that kindergarten classmate of ours whose dexterity on the teeter-totter outpaced our own, or that compilation, the mere mention of which causes the heart to relay to the brain that now might be a fine time for another listen.

Everyone who loves the music of The Beatles has a story about how they came to love them. A stoner friend in high school introduced them to the “White Album.” They turned on the TV one night and there were the lads larger than small-screen, black-and-white life on The Ed Sullivan Show. “Penny Lane” started playing on the car radio during an otherwise routine Saturday drive to grandma’s and a child discovered that life would never again be what it had been before those three amazing minutes.

If one was not there when the Beatles happened, coming along later as so many fans have, there’s a strong chance that the so-called “Red Album,” released in 1973, is their point of romantic entry, just as it could be the one that the most amount of people have in common.

If one was not there when the Beatles happened, coming along later as so many fans have, there’s a strong chance that the so-called “Red Album,” released in 1973, is their point of romantic entry, just as it could be the one that the most amount of people have in common.

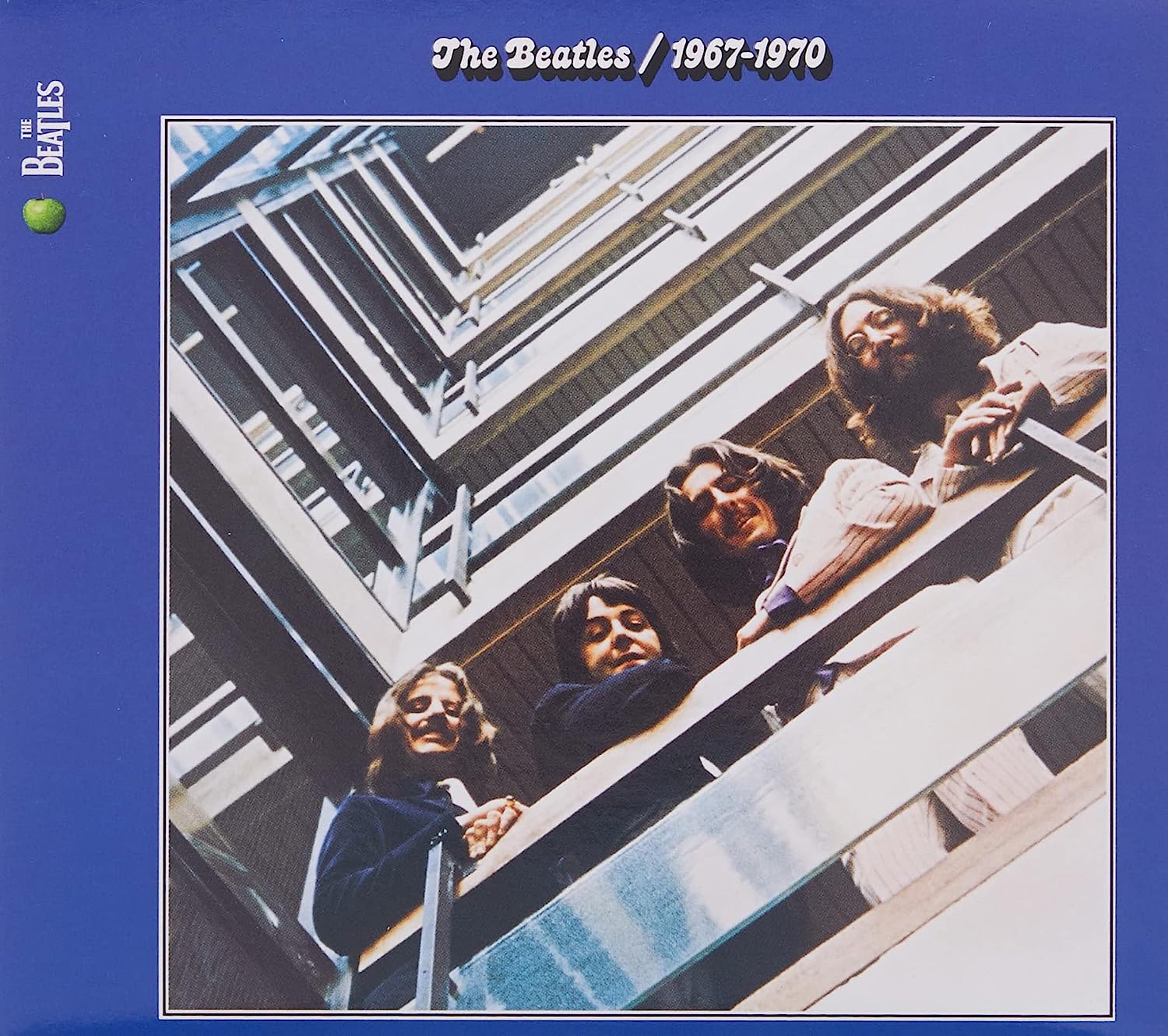

There’s the “Blue Album,” too, released the same year, but presented with both—and given that a person is likelier to be hooked on melody before anything else, musically speaking—those selections from 1962 to 1966 carry the live-long listening day like few, if any, curated collections of songs do.

The Beatles as an active band had been gone for 30 percent of a decade by that time. Or, put another way, the span of years from A Hard Day’s Night to Sgt. Pepper, or “Please Please Me” to “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

The musical world would have seemed like it had slowed down without the Beatles in it. Along came these reminders of what the Beatles had been, which also suggested what the Beatles could be for anyone going forward as the kind of listener who falls in love with what they love the same way they cue up a record again and again.

Related: The author takes a new look at the Beatles’ Decca audition recordings

Such is the way of all successful romantic relationships, and the “Red Album,” in particular, seemed to understand precisely how this is so in the musical sense. Love may always be just beginning, no matter how far back it goes.

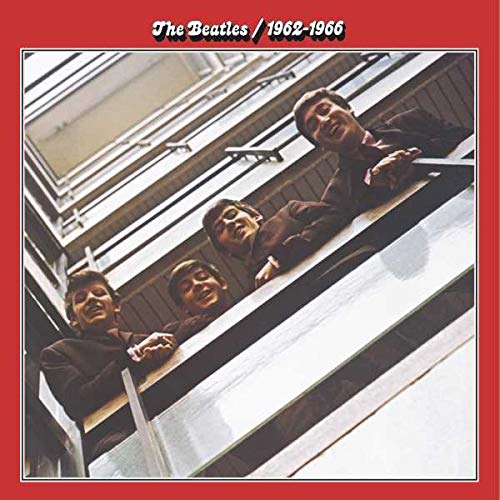

Officially titled 1962-1966 and known by everyone who has ever come in contact with it as the “Red Album,” the record originated as one of the final acts of then-Apple Records manager Allen Klein. If you wanted new Beatles product in 1973, this would have been it for you.

Fans may have known that the Hollywood Bowl shows had been recorded, but it wouldn’t be for another four years until those tapes were whittled down into a single LP. Likewise, there were the fan club Christmas flexi-discs, which would have made for a charming album—though one lacking in formal music—but if you hadn’t gotten them when they first came out, you weren’t getting them now.

Fans may have known that the Hollywood Bowl shows had been recorded, but it wouldn’t be for another four years until those tapes were whittled down into a single LP. Likewise, there were the fan club Christmas flexi-discs, which would have made for a charming album—though one lacking in formal music—but if you hadn’t gotten them when they first came out, you weren’t getting them now.

Intrepid hunters might have acquired a bootleg or two from the Get Back sessions, which had to have been exciting. Then again, there wasn’t a lot of spilled gold to be found from those sessions in the first place, and a bootleg album of 12 or 15 songs wasn’t likely to shoulder Rubber Soul out of the turntable rotation for more than a spin or two, as it goes with curios.

The strange reality of the “Red Album” is that if you were there and into the Beatles, you were probably disappointed that this and its compatriot the “Blue Album” were all you were getting; but, if you weren’t into the Beatles, there was hardly a record more apt to hook you on their music for life.

The strange reality of the “Red Album” is that if you were there and into the Beatles, you were probably disappointed that this and its compatriot the “Blue Album” were all you were getting; but, if you weren’t into the Beatles, there was hardly a record more apt to hook you on their music for life.

The cover was an outtake from Agnus McBean’s 1963 photoshoot at EMI House that produced the crucial, welcoming image—an energetic visual salutation—of Please Please Me, a composition that was to be reprised half a dozen years later (also courtesy of McBean), as fans knew from the “Blue Album.”

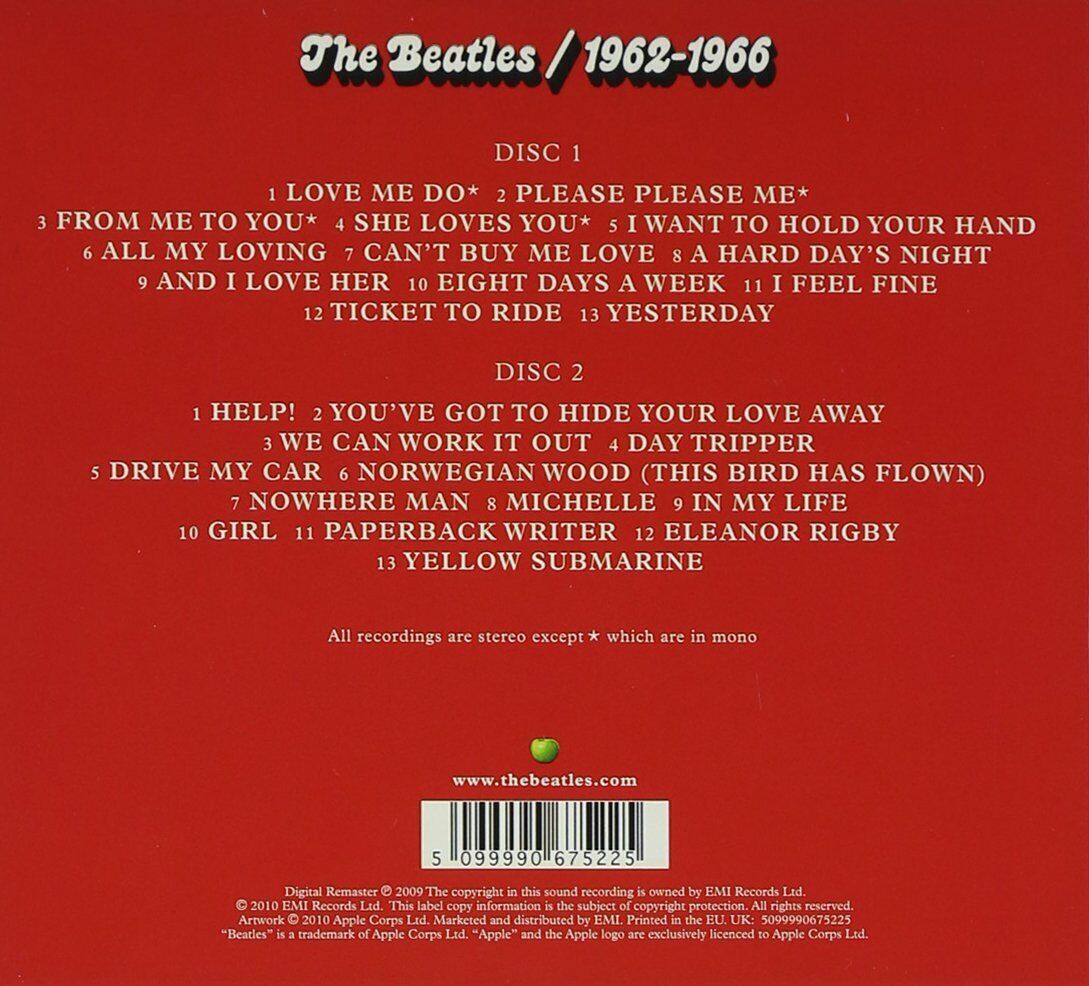

The music ranges from debut single “Love Me Do” through to the Revolver phase, and what you get is a taste of everything the group did within that span, which makes for both a strange and effective way to proceed.

Take Rubber Soul, for instance. Does anyone ever just listen to a part of the album? You play it or you don’t. In playing it, you play it straight through; it’s unlikely that you’d skip around.

But on the “Red Album,” we’re teased with such a record, which results in us being blown away and wanting more. We get six cuts from Rubber Soul. And as we desire more cuts still—because how could you not?—we’re swept into the material from 1966, and that holds sway. Our attention transitions, and becomes fixed on another point of entry, with all of these various points of entry adding up to an immensely pleasurable whole.

But on the “Red Album,” we’re teased with such a record, which results in us being blown away and wanting more. We get six cuts from Rubber Soul. And as we desire more cuts still—because how could you not?—we’re swept into the material from 1966, and that holds sway. Our attention transitions, and becomes fixed on another point of entry, with all of these various points of entry adding up to an immensely pleasurable whole.

In William Sloane’s dynamic, unclassifiable 1937 novel To Walk the Night, a character decrees that the only unforgivable sin is weakness. Borrowing the concept, it’s worth suggesting that the only unforgivable sin for a Beatles listener is to overlook their early recordings. Don’t get snared in the recency trap, even with recordings from the 1960s.

What has become popular critical opinion—that the Beatles of 1969 were more inventive than the Beatles of 1963—is also one of the chief fallacies in all of popular music. A wizard tasked with creating a hundred patents a year would be hard-pressed to invent more than those early Beatles did. No one used chords the ways they found to use chords, and it was that Beatlesesque marriage of melody and rhythm that rock and roll had never known nor conceived of prior to the advent and rise of this Liverpool beat group.

A Beatles song had as much drive as a Chuck Berry or Elvis Presley number, but could also be as tuneful as any air conceived by Schubert or Handel. This was new, and it has remained startling. There is, for example, nothing in human history that sounds like “She Loves You” sounds. If there ever is again, that might be the tip-off that the world has come to its end.

These Beatles of the early years were master melodists. To impressionable ears, the very tunes of “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Please Please Me” and “From Me to You” are enough to make a person believe that never has joy been more effectively codified in musical form.

A child remarks that they just feel good today, and in that pithy summation is a universe of refulgent feeling. The child, in a manner, has said all, because the child has conveyed how we all wish to feel.

These early numbers function similarly. To be walloped by them in succession is to be the salubrious form of dazed, and also cognizant of possibilities within the world. For just as nothing sounds like the Beatles of the “Red Album” sound, you start to think of what could be over what already is.

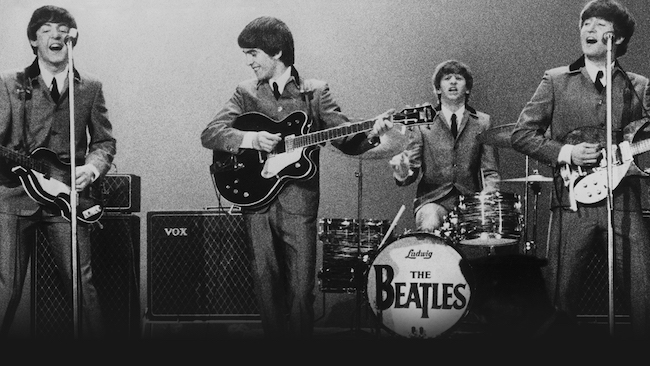

The Beatles on the set of Top of the Pops, to perform “Paperback Writer,” on June 16, 1966 (Photo: Apple Corps Ltd.; used with permission)

Paul McCartney has one of the largest gifts for melody a human has ever possessed. When his songs sometimes lacked bite during the Beatles’ later years, they survived and thrived because of that melodic gift. When they had both the bite and the melody—as with “Hey Jude”—McCartney compositions immediately registered as works that could be around thousands of years after you are not.

Lennon did the bulk of the writing through 1965. The competition between the two men as composers was real, and that competition, combined with a lot of fire in the bellies of both Lennon and McCartney, caused the former to up his melodic game such that it sometimes reached the McCartney level.

The same can’t be said about Lennon later on. “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “A Day in the Life” are tour-de-force pieces of compositional brilliance, but it’s not because of melody.

Their power comes from other channels, just as the power of “Don’t Let Me Down” is the power of the raw confessional. Lennon lost something that he once had. A vestige of what that was checked in every now and again—“Oh Yoko!” for instance, in the post-Beatles timeframe. The “Red Album” Beatles, though, had everything you could wish to have.

One might say that they lacked for worldly wisdom, given all that they still had to go through and experience together. And yet, there is no wiser song than “She Loves You,” no wearier lament of the need to get away than “Ticket to Ride,” no testament to romantic epiphany of greater potency than “Can’t Buy Me Love.”

There could well be some log of the cosmos that documents what records have been played the most times, and though few people cite the “Red Album” as their favorite Beatles LP—if that’s truly what it is—it could certainly be what people have played the most, Beatles-wise. To play it is to love it.

Playing the “Red Album” also feels like loving one’s self—coming home again to an entity beyond house and hearth, and being one entirely of heart. Well, heart and ears. And hooks. Definitely hooks. To choose to be ensnared by love is to never be trapped. It’s to be a part of something wonderful. That’s what listening to the “Red Album” is like, and why it represents music’s version of eternal love.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI won the Red and Blue Albums in a radio station contest in 1973. Finally! “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Ticket to Ride” in TRUE STEREO, right?

But Noooooooooooooooo!!!

This was the hold the Beatles still had on America in 1973. The Blue Album was #1 the last week of May. Followed by “Red Rose Speedway” for three weeks in June. Followed by “Living in the Material World” for FIVE weeks in June and July.

“My Love” was #1 for four weeks in June, followed by “Give Me Love” for a week in July. Followed by “Will It Go Round in Circles”, creating a “Get Back” reunion at the top for seven weeks.

Take that, Oasis!