Al Kooper was selected for a “Musical Excellence Award” at the 2023 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony on November 3 at the Barclays Center in his birthplace of Brooklyn, New York. He was born on February 5, 1944.

In 2001, 2004, 2013 and 2018 I interviewed Kooper about his 1965-1970 recording endeavors with Bob Dylan. We also discussed The Band, recording with the Rolling Stones and his landmark Super Session album with Michael Bloomfield and Stephen Stills.

You first met guitarist Michael Bloomfield on a classic Dylan session. Tell us about that day.

Michael and I met on the “Like a Rolling Stone” session. I had read about him in Sing Out Magazine, and saw a picture of him where he looked a little more rotund than he was when I met him. We really hit it off, and we played together on that. It never even occurred to me that someone my age and my color could play like that. I had never seen that, or heard that, up to that day. [The scene is depicted in the 2024 biopic, A Complete Unknown.]

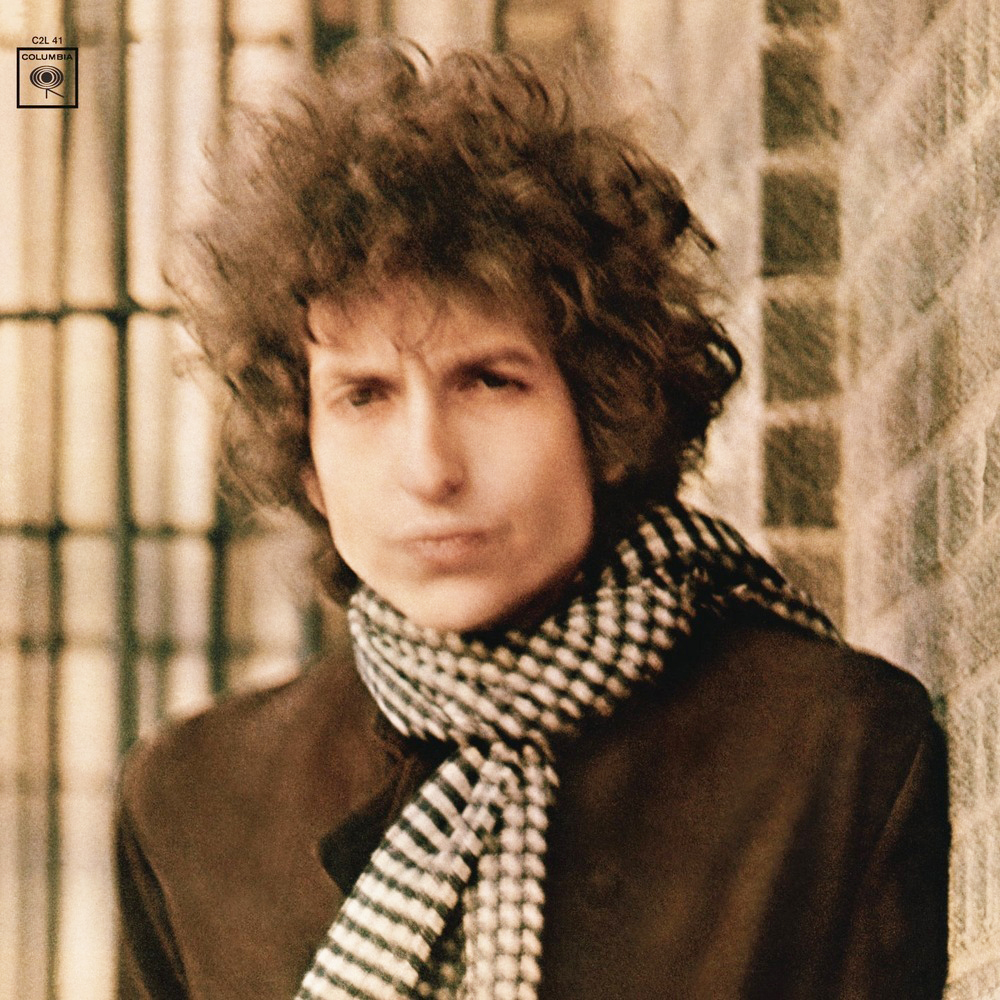

Why does Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde album hold up so well?

The main reason is the chemistry of the participants. And the other reason would be the songwriting. [Producer] Bob Johnston had tried to get Dylan to record in Nashville in late 1965. He knew about the chemistry. I think he felt more comfortable there because he lived there and he knew all the musicians intimately. I had never seen what they did in Nashville. They just hired the musicians and they were booked until we were done that day, or night, or whenever it was. They didn’t have any other distractions. There were no breaks. I had never worked like that in the studio, so it was a big eye-opener for me. During the day, Bob [Dylan] had a piano in his room and I would go up to his room and he would teach me the song and because there were no cassette machines in those days, I would play the song over and over for him and he would write the lyrics. I was blown away by the whole thing, just the concept of, “Hey, we can spend more than one hour on a song.”

At the time, did you know you were recording some potent songs with a long shelf life?

I learned it after I did Highway 61 Revisited. One time during Blonde on Blonde, I started thinking, “Wherever my hands move next it’s gonna be around for all time.” Then I said to myself, “Will you please shut up and just do what you do?” It can completely freak you out if you thought like that.

Tell us about the studio where Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album was recorded.

That was for Columbia Records and they had the studio in the same place as their offices. They then moved the studio further east, to 49 E. 52nd. Street [in Manhattan]. They duplicated the studio they had earlier on 7th Avenue. There were three studios there, so they could do a lot more sessions.

Tom Wilson, who produced “Like a Rolling Stone,” gets overlooked in history.

Yep. Great guy. So does John Simon [who produced Blood, Sweat & Tears’ debut Child Is Father to the Man, featuring Kooper], by the way. Tom earlier worked for Savoy Records. He was a very bright guy, a very high-class guy. He was bright and he talked about very erudite things, and he really saved my life that day on that Dylan “Like a Rolling Stone” session. They had just moved Paul Griffin from the organ to the piano. I was invited just to watch, and I said, “Man, why don’t you let me play the organ? I got a great part for this.” Which was bullshit. I had nothing. And he said, “You’re not an organ player.” Then they came to him and said, “Phone call for you Tom,” and he just went and got the phone. I went into the studio and sat down at the organ. He didn’t say no. That was the moment he could have just thrown me out, and rightfully so. He didn’t. And that was it. That was the beginning of my career.

Listen to early rehearsal takes of “Like a Rolling Stone”

You reviewed the first Band album for Rolling Stone.

I knew what was happening in 1968 with John Simon producing the debut Band album and should have had an early glimpse of what was going on. But at the time I was staying home and not going out. John would call me and say, “You gotta come hear Robbie [Robertson]’s record.’ That’s what he called it. I didn’t know what it was. Then I heard it when it was done at [Band manager] Albert Grossman’s office. I went, “Holy shit! This is ridiculous. I didn’t think it was gonna be like that.” I kicked myself for not going to the sessions since I was invited to those sessions. John Simon went from doing the Blood, Sweat & Tears album to doing that record, one after the other.

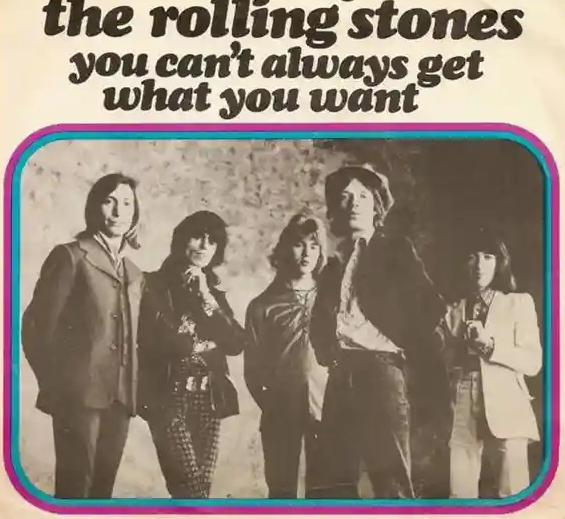

You recorded with the Rolling Stones on “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” [Mick Jagger’s solo release] “Memo From Turner” and “Brown Sugar.” How did that come about?

I saw the Rolling Stones in June of 1964 at Carnegie Hall. It was hard to hear them because of the fuckin’ women going berserk. Different from the Beatles. And I caught them on The Ed Sullivan Show. I later knew Brian Jones from the June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival where I was the assistant stage manager. After I completed The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield & Al Kooper, I went to London and I was picked up at the airport by my good friend [producer] Denny Cordell. He then said, “The Stones’ office called me and asked if you feel like playing on a few recording sessions with them. I said, “How did they know I was gonna be in England?” And Denny replied, ‘I didn’t say a fuckin’ word.” The next day we left the hotel and went shopping on Kings Road and ran into Brian Jones in a shirt store, who asked, “Are you gonna play the session, Al?” I could never say no to these people. So I went. The main reason they wanted me was that Nicky Hopkins, their regular keyboardist, was in the United States.

I went to the studio. Bill and Charlie were there. I had met them before with Bob Dylan. I sat at the organ and met Jimmy Miller, the producer. Mick and Keith bolted through the door. Mick wore a gorilla coat and Keith a hat with a long feather. Everyone sat around and they passed out acoustic guitars to anyone who could play acoustic guitar. Then Mick and Keith played acoustic guitar and ran down the tune for everybody with the chord changes and the rhythm accents. There was a conga player in the room who rolled hash joints. It was decided that I would play piano on the basic track and later do an organ overdub. I got a groove going which I heard on an Etta James cover version of [Sonny and Cher’s] “I Got You Babe” that worked. Keith picked up on it with a guitar part that meshed with my organ part. Jimmy Miller showed Charlie an accent and he just couldn’t get the part. Jimmy sat down at the drums and stayed there and played on the take. Charlie was unhappy but he hid it completely. Very graceful. He didn’t throw a temper tantrum but said “Why don’t you just play the drums?” He said it sincerely. He didn’t say it like I would have. Bill played bass, I played piano. Mick and Keith played acoustic guitars. Keith then did a lead electric guitar part and I overdubbed the Hammond organ. We were out there together. Brian Jones was in the corner on the floor reading a magazine. The recording went on for about four hours. Then all sorts of food arrived later in the night: racks of lamb, salads, wines. Not a cheeseburger break like back in the States.

The next night Mick and Keith picked me up at the hotel, they were in the lobby, and we cut a track [“Memo From Turner”] for Performance, the film Jagger was working on. It’s not the version in the movie or soundtrack. I played guitar. A little later, 1971, when they were working on Sticky Fingers, there was a birthday party for Keith at Olympic Studios and I was invited and went. They cleared the room and set up to record. George Harrison was there and he declined to play. Eric Clapton, myself and Bobby Keys joined. I thought the song [“Brown Sugar”] was great. They might already have cut it on the ’69 U.S. tour. This was a completely different take. That was the night I met George. He was very nice. Over a period of time I spent a lot of time with him. And then once when I was in a lull in my career and wasn’t making much money and I lived in this not-great place, at 11:00 p.m. one night the doorbell rings and I wondered who the fuck this is? I look at the curtain and it’s George. I never gave him my address. I opened the door and said, “There’s a Beatle at my door!”

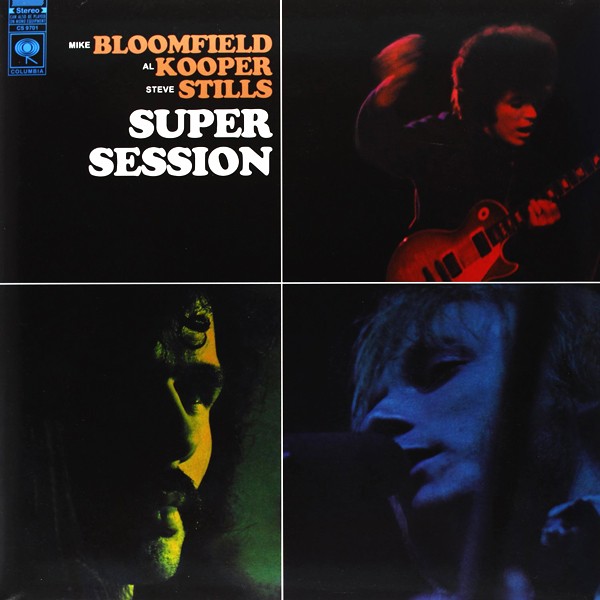

How did you and Michael Bloomfield and Stephen Stills come to record Super Session?

Both of us [Kooper and Bloomfield] had just played on [Moby Grape’s] Grape Jam album. That gave me the inspiration to say, “Why don’t we make a record?” I wanted to make a record that was very simple, not a “weighty” record. I said, “Let’s make a rock ’n’ roll record based on the way jazz records are made.” You pick a leader, or two leaders, and then you just go in, you pick some songs, you pick sidemen, and you just blow. No rehearsing or anything. I was very dissatisfied with the way he [Bloomfield] was recorded up to that point. His live playing was like 300 times better than his performance on a record to that point. I wanted to put him in a situation where he was uncluttered by his situation in the recording studio, which must have inhibited him. So I made it as uncomplicated as possible for him. I felt really vindicated that I had done that.

And, the other thing was, we both had been kicked out of our bands. Stills, too. He was out of his band [Buffalo Springfield]. So Stills fit in, in a really weird way, because none of us had anything at stake, and that was the whole point of that record. There was no career thing goin’ on. We just did it because we played music. That’s what’s so wonderful about that. Super Session wasn’t made to sell records.

Related: More about the making of Super Session

But Super Session did end up selling a lot of records.

I had no expectations for that record, none whatsoever. I just did it because I had a job as a producer and I had no one to produce, and I went in because I thought Michael and I should make a record together, because of how our careers were parallel. And also because we were friends, and it would be fun to work together. Michael brought Eddie Hoh (drummer) in, and I brought Harvey Brooks in (bass). The most important thing is the playing of the two principals, Bloomfield and Stills. It’s timeless. Bloomfield’s stuff is some of the greatest blues playing that there ever was. And it was a non-vocal Stephen Stills, owing to contractual limitations and restrictions. I regretted that a lot that night. But I said, “If he sings, we’ll never be able to put this out.” I knew Stephen was a great guitar player and that was the key thing. But I had to take a lot of shit from David Crosby when that came out. “Why the fuck didn’t you let him sing?” I told him and he didn’t even listen to me.

Listen to “Albert’s Shuffle” from Super Session

The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper followed that. It was a late ’68 live date taped at the Fillmore West on the heels of Super Session. What do you think of that album?

That was a weird record. We did that because people gave us some shit about the confines of the studio, and said it was slick. So I said, “Let’s go down and dirty and play a gig and record it live. Nobody is gonna yell studio at us for that.” So that’s what we did. And it actually was a little too down and dirty.

Many of Kooper’s recordings are available here. His memoir, Backstage Passes & Backstabbing Bastards, is available here. Author Harvey Kubernik’s many music books are available here.

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper turned me on to Mike. I had been listening to old blues guitarists and of course Clapton, Hendrix, and Green. Michael was a revelation. He was playing blues but it sounded fresh and spontaneous and more than minor pentatonic. This opened the door to east coast blues which was more vital and alive. Al Kooper was in the mix in those days. He had a sound and an approach that made him easy unique. Like Nicky Hopkins he changed the sound of recording sessions. He added the special sauce that makes them memorable.

I love Al Kooper. I can’t think of a more under-rated musician who is more important in the history of rock music.

Al Kooper is my favorite American musician. I first became aware of him when I got Projections by the Blues Project for Christmas (I was expecting Are You Experienced). His BS&T album is better than those that followed. Super Session is a “desert island” album. Live Adventures is an album I bought when it first came out. I still have the original. I always look for his albums when I peruse the vinyl stacks at record stores. So happy to see him getting this award.

Bloomfield never has sounded better than in that studio session with Al producing!

BB King he’s never heard anything as “sweet a salty”! King also referred to Michael as “his son” saying he was the greatest white American electric guitarist there was! All of it really good stuff!! Really good!!

If you’ve never read Al’s autobiography, “Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards”, find one NOW! I’ve read a lot of rock bios – currently on Geezer Butler’s, which has been better than what I was expecting – but his is quite possibly the best. Among my favorite Al stories was how he and Bloomfield were getting REALLY high one morning, and Al noticed Mike was eating…dog biscuits. And continued to eat them even after Al pointed out that they were…dog biscuits.

I thought Bloomfield’s best guitar recordings were on “The Trip”. His middle pickup never sounded better.