Yes’ Chris Squire, Steve Howe, Alan White, Jon Anderson and Patrick Moraz from the inside gatefold of Relayer (Photo: Jean Ristori)

When you lose a key member of a band, who in turn elicits better results by the time the next album rolls around? The band or the listener?

Such was the case for Yes. In the short space between the release of their double-album masterwork Tales from Topographic Oceans in late 1973-early 1974 to the November 1974 release of their seventh studio album, Relayer, the group was whittled down to a four-piece after the departure of keyboardist Rick Wakeman, who had, sans subtlety, expressed his dissatisfaction with the direction the band was headed musically.

The group—vocalist Jon Anderson, guitarist Steve Howe, bassist Chris Squire, drummer Alan White and Wakeman—was halfway through a five-month concert jaunt in support of Tales when Wakeman informed them he wanted out. His three-year tenure had admittedly been a rollercoaster ride: he had opted out of an invitation to join David Bowie in the Spiders from Mars full-time and was composing and releasing intermittent solo projects. But such was his artistic (read: difficult) mindset, coupled with his open indifference during the tour, while trashing the group’s songs in the U.K. music press, (as he groused in his 2007 memoir, “Half the audience were in narcotic rapture on some far-off planet and the other half were asleep, bored sh*tless”), that making the decision to leave Yes essentially a no-brainer.

Wakeman’s exit was made public on June 8, 1974, and the quartet entered Farmyard Studios in Buckinghamshire, England, to start rehearsals and then auditions for a keyboardist. One of the more surprising music asks was for Greek musician Vangelis. Years before his Academy Award-winning score for Chariots of Fire, Vangelis was actually a well-known musician across Europe, composing for film and undertaking solo projects. Queried by Anderson, whom he had met in Paris during the Topographic Oceans tour, Vangelis shipped his keyboards north and traveled to England for a serious audition.

Fate, however, would not play in his favor. As with Wakeman, his strong personality and non-committal attitude toward the material hampered the process. Work visa issues and a rejection from the U.K. Musicians Union, topped by his fear of flying—obviously a touring requirement—proved obstacles that were too great to surmount for Yes. However, on the recommendation of journalist Chris Welch from Melody Maker, Swiss keyboardist and Yes fan Patrick Moraz came in, utilized Vangelis’ equipment and, barring any further delay, the band was now set to start recording its new album.

The group was committed to recording Relayer at Squire’s home, New Pipers in Surrey, with a 24-track recording desk in the basement—viewed as a cost-cutting measure enveloped in a casual environment—and utilizing Eddy Offord, their engineer, mixer and previous co-producer.

The suggestion weighed heavily on turning in something completely the opposite of the perceived “tightly structed” cadence and concept of Topographic Oceans, and to that end it was Anderson and Moraz who first came with the framework for the only song on side one, “The Gates of Delirium.” At nearly 22 minutes, the magnum opus has various themes that hit multiple peaks and valleys in the overall arc of the melody. Portions were conceived by Anderson on cassette as he and Howe systematically kept the pieces in order while Anderson would continue working out more sections.

Overall, Anderson had envisaged the song as a cry to battle in the spirit of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. For further inspiration, Moraz brought him a copy of Philippe Druillet’s graphic novel Délirius, whose protagonist Lone Sloane, a cosmic freebooter and rebel, struggles against dark gods, robotic entities and alien forces. Amid the period-correct prog-style theatrical gymnastics from Anderson, bombastic keyboard flourishes, chaotic time signatures and crashing sound effects, it somehow manages to hold up as an attention-grabbing piece of work. The only downside was Anderson’s criticism of its effectiveness on record that appeared better rectified on a future tour in a concert setting.

Side two opens with “Sound Chaser,” a somersaulting, outer-space-y nine-and-a-half-minute take that has Anderson running the Preakness with Squire, who then proceed to hand over the reins to Howe’s jazzy-flamenco stylings. Melding into a cohesive, pulsing middle and more of Howe’s squealing solos, the song ends with some abbreviated chants and (for a song of this length) a semi-abrupt conclusion.

The album closes with the nine-minute “To Be Over.” A song long left behind by Howe in the late ’60s, he revived it for Relayer with a trip down the Serpentine in London’s Hyde Park and help from Anderson’s first-spun lyric “We’ll go sailing down the stream tomorrow, floating down the universal stream, to be over.” The raga-hippy vibe comes off strong in just the first few stanzas, courtesy of Howe’s use of electric sitar. Anderson’s layered vocals create a soothing cascading pattern, which are complemented by what would be considered a more straightforward accompaniment, especially Moraz’ use of a strings program on the Mellotron and White’s tasteful percussion throughout.

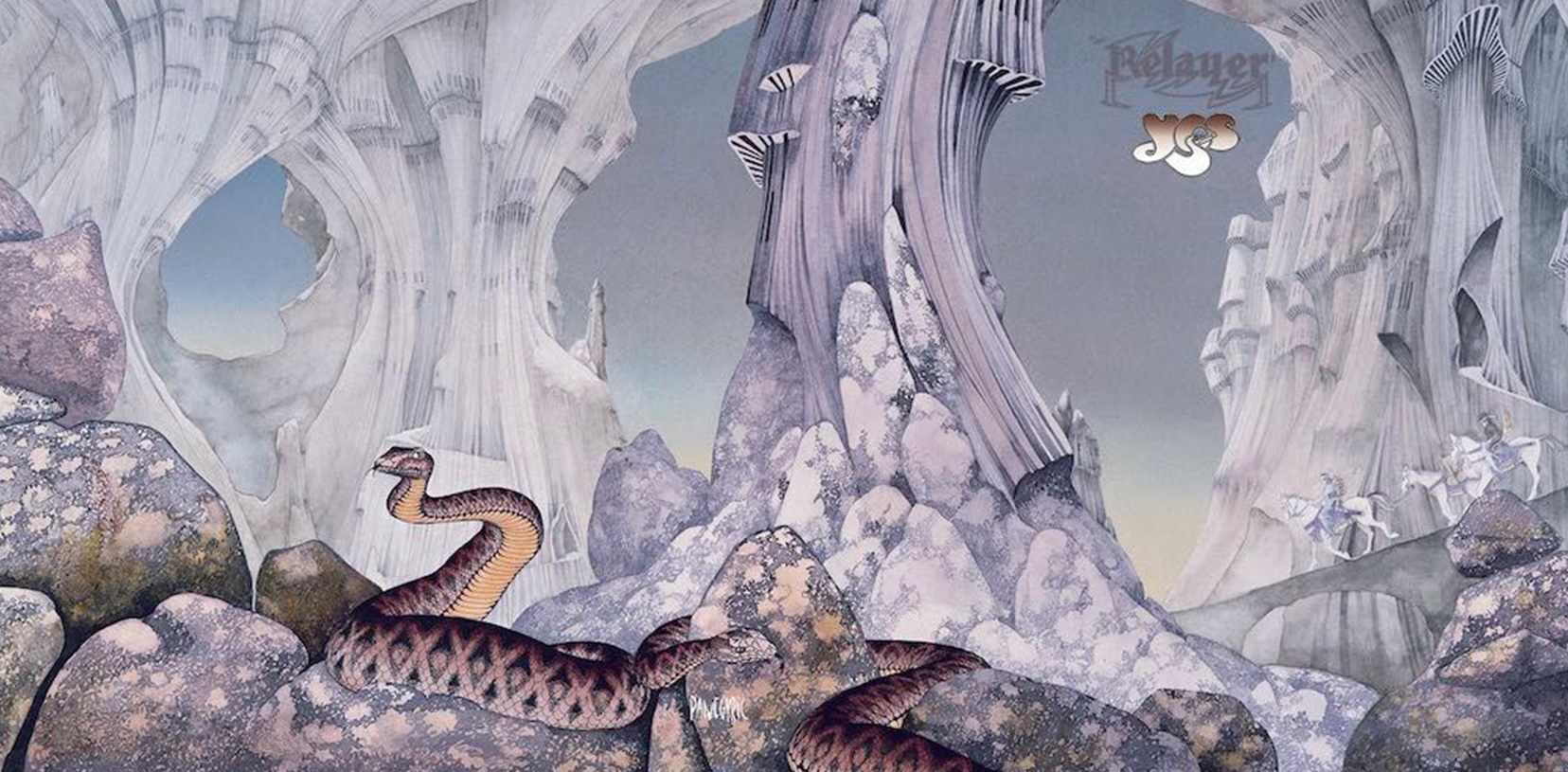

As with most of Yes’ creative artwork, the album cover for Relayer was designed by Roger Dean, who had worked with the band since 1971 and who had also created their logo. Derived from a watercolor sketch he did in college, the jacket painting capitalized on the otherworldly representation that was identified with the band. “I was looking for the kinds of things like the Knights Templar would have made,” he explained in a 2004 interview. “The curving, swirling cantilevers right into space.”

Relayer was released on November 29, 1974, in the U.K. and December 5 in the U.S., reaching #4 on the U.K.’s Official Charts and #5 on Billboard’s top 200, reaching gold status in the States. As was fashionably custom for any band worth their salt, Yes headed out for the Relayer Tour, a nine-month North American and U.K. jaunt from November 1974 thru August 1975 that saw them perform the album in its entirety and ended with a headlining gig at the 1975 Reading Festival, sharing the bill on day two with the Ozark Mountain Daredevils, Thin Lizzy and Supertramp.

Moraz’s tenure with Yes was relatively brief. Following a planned break where the group focused on solo albums, he departed during early sessions for the band’s follow-up to Relayer, 1977’s Going For the One. His replacement? None other than Wakeman.

A 2003 remaster of Relayer added three bonus tracks: “Soon,” a 4:18 edit of the ending of “The Gates of Delirium”; a 3:13 edit of “Sound Chaser” and a studio run-through clocking in at 21:16 of “The Gates of Delirium.” The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Yes perform the complete Relayer live in 1975

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe news hadn’t reached me before I went to see Yes for what turned out to be the Relayer tour. I walked out. I was there mostly to see Wakeman. Moraz was, to me, unlistenable.

Then you, sir, are a fool. Relayer is a masterpiece and Moraz a superb player, just different to Wakeman. Yes needed the change at that time.