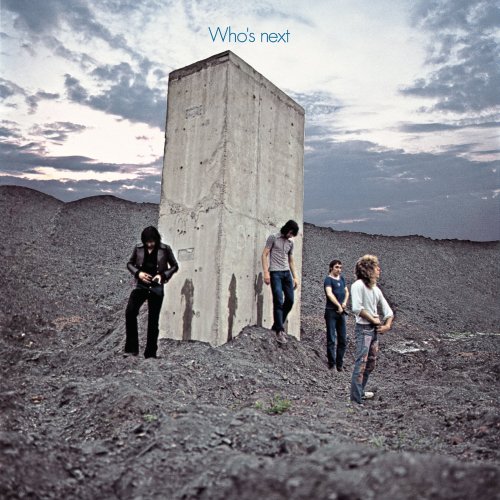

The Who’s best-selling album, Who’s Next, is enshrined as a genre cornerstone, its songs locked in perpetual rotation on classic rock radio while two signature tracks have been flogged relentlessly as TV theme songs. There’s no small irony, then, in its genesis in failure: the collapse of songwriter, guitarist and pop conceptualist Pete Townshend’s most ambitious and, ultimately, unwieldy multimedia project, Life House.

The Who’s best-selling album, Who’s Next, is enshrined as a genre cornerstone, its songs locked in perpetual rotation on classic rock radio while two signature tracks have been flogged relentlessly as TV theme songs. There’s no small irony, then, in its genesis in failure: the collapse of songwriter, guitarist and pop conceptualist Pete Townshend’s most ambitious and, ultimately, unwieldy multimedia project, Life House.

Like other art school rockers, Townshend saw The Who’s music as more than bids for chart glory. He had pushed beyond the structural and thematic constraints of three-minute pop songs since their earliest singles, graduating from generational anthems to the elaborate adultery narrative in the mini-suite of “A Quick One, While He’s Away” and the cheeky faux radio broadcast of The Who Sell Out.

Emboldened by the success of Tommy, the band’s groundbreaking 1969 “rock opera,” Townshend envisioned Life House as a movie and album projecting a sci-fi fantasy in which rock saves a dehumanizing world, a concept fusing his passionate connection to the Who’s fans with his immersion in the teachings of Indian spiritual master Meher Baba and Sufi concepts of music’s spiritual powers. Yet as the project’s narrative concept and philosophical underpinnings mutated in scale and intention, Townshend found himself overwhelmed. Meanwhile, a growing rift with co-manager Kit Lambert, who had previously championed Townshend’s ambitions, was irrevocably deepened by Lambert’s descent into hard drugs. On the verge of a nervous breakdown, Townshend abandoned his fever dream of a transformative pop art masterpiece.

The Who in the early ’70s (clockwise from top left): Keith Moon, John Entwistle, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend.

That left the Who with a shelf of 19 songs mapped out in Townshend’s detailed demos. Lambert’s retreat, meanwhile, coincided with the engagement of Glyn Johns as recording engineer, a change that would prove crucial to the project: Johns’ rise through sessions with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and other major acts placed him at the forefront of technical strides in multi-track recording, and he pushed the band to move recording to London’s cutting-edge Olympic Studios after an initial session in early April 1971 with the Stones’ mobile studio at Mick Jagger’s Stargroves manor in Hampshire.

Life House may have been scuttled as an album, but Townshend’s new songs proved a valuable consolation prize. In all, eight of the full-length’s nine songs were culled from the project, with other tracks to surface on subsequent Who albums and Townshend’s full-length solo debut Who Came First. His demos revealed a new, timely experimentation with electronic music using VCS 3 and ARP analog synthesizers, enabling him to create complex, shape-shifting sonic beds for key tracks including “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” started during the Stargroves session, and what would become the album’s opener, “Baba O’Riley,” recorded at Olympic.

Against a lattice of pulsing synth phrases, Townshend embroidered an electronic fugue, overlaying a contrasting layer of flickering arpeggios to provide the song’s foundation as piano, guitar, bass and drums enter, laying a path for Roger Daltrey’s vocals. Glyn Johns would later recall that Townshend’s looped synthesizer sequence brought an added benefit in pulling Keith Moon, whose excitable drumming could veer off tempo, into a rhythmic lockstep.

Related: Our feature on Townshend’s song, “Teenage Wasteland,” from the Life House sessions

The lyrics’ allusions to youthful defiance in a “teenage wasteland” echoed the anomie of Townshend’s earlier songs, but the sonic palette was new; Moon’s rock-steady tempo would finally break free by design during the song’s concluding instrumental passage, decorated with vivid violin figures that matched the accelerating drum track.

The band’s more familiar command of guitar pyrotechnics drives the set’s second track, “Bargain,” with Townshend balancing acoustic rhythm guitars against his own slashing electric fills, sinuous synthesizer lines, John Entwistle’s loping bass and Moon’s explosive fills. Daltrey’s ferocious vocals on the early verses and choruses contrast with a gentler, acoustic bridge sung by Townshend, who softens the song’s projection of a lover’s determined ardor with a more vulnerable tenderness before Daltrey reclaims the lead and restores the track’s fury on the final verse and chorus.

Freed from a narrative context, the songs loosely alternate social commentary with more conventional romantic tropes. “Love Ain’t For Keeping” frames an erotic interlude with affectionate domestic details, followed by a more caustic snapshot of marital discord in the set’s lone non-Life House track, John Entwistle’s “My Wife,” showcasing the bassist’s frantic vocal and lively horn charts.

On the original album, the Townshend track, “Love Ain’t For Keeping,” appears in a brisk 2:10. On the new collection, the muscular Take 14 from the Record Plant spans nearly five minutes.

“The Song is Over,” another Life House orphan, meanwhile, conflates the original concept’s mystical view of music with the end of a love affair.

Daltrey’s dramatic vocal and the song’s instrumental sweep ultimately overshadow the romantic narrative with an anthemic power that by this point was an established earmark of the band’s appeal. That equation of music with emotion is echoed more hopefully in “Getting in Tune,” followed by the cheerful escapism of “Going Mobile,” a Townshend vocal that imagines an untethered life on wheels as a metaphor for freedom.

The mood darkens ominously on the set’s penultimate song, “Behind Blue Eyes,” one of the album’s strongest and most tautly focused performances. As sung by Daltrey, the lyrics peel away layers of fear, anger and pain with an emotional turbulence that erupts following the subdued lament of the opening verses:

“No one knows what it’s like

To be the bad man

To be the sad man

Behind blue eyes…

No one bites back as hard

On their anger

None of my pain and woe

Can show through…”

The singer’s anguish builds, then curdles into a threat: “My love is vengeance that’s never free” strikes at the heart of the song’s confessional knife edge, punctuated by the arrangement’s explosion into a ferocious bridge spiked with Townshend’s stinging guitar phrases and Moon’s percussive bombardment. Daltrey matches the instrumental violence with the song’s darkest lyrics, pleading, “When my fist clenches, crack it open, before I use it and lose my cool.”

Where “Behind Blue Eyes” scores with lethal economy, clocking in at under four minutes, the album’s final track swings for the fences with the completed version of the first song recorded for the set. “Won’t Get Fooled Again” opens with Townshend’s other virtuosic synthesizer piece, triggering organ figures in staccato volleys before the full band crashes into view behind another defiant Daltrey vocal on a call to arms fueled by a sense of generational betrayal and deep cynicism about establishment politics. The arrangement indulges the band with plenty of room to flex its formidable firepower in creating a finale that’s epic in both length and power.

Who’s Next, released in late July 1971, made its chart debut on Aug. 14, reaching #1 in the U.K. and #4 in the U.S. Shorn of high concept, it triumphs through songcraft and performance. The Who would return to larger-scale projects with Quadrophenia and reboots of the Tommy score, while Townshend would return to Life House for concert and radio incarnations as well as his own adaptation of The Iron Man, the Ted Hughes sci-fi fable that would also yield Brad Bird’s 1999 animated film.

Related: The top selling albums of 1971

[The album’s spectacular 2023 expanded editions are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. Tickets for The Who’s 2025 farewell tour are available at Ticketmaster and here.]

10 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationRoger Daltrey’s scream on “Won’t Get Fooled Again” still gives me the shivers every time I hear it. It’s simply primal. Oh, how I love that song.

Multiple Whogasms is more apropos

After seeing them in concert supporting Who’s Next, we decided the name of the band should be Whew.

The definitive desert island disc. Great article, Sam….thank you!

A forgotten but absolute masterpiece from this album was the track WATER. If you listen to The Who do it live at Isle of White in 1970, as far as Im concerned, that song saved their careers!!

Every time i hear Behind Blue Eyes, i think the lyrics goes “No one knows what it’s like to be a Batman”!

You forgot to mention the other songs, that The Who recorded for the Who Ss^ Next album: “I Don’t Even Know Myself”, “Lets See Action”, “Pure and Easy”, “Too Much of Anything”, “Naked Eye”, “Time is Passing” and John Entwistle s`”When I was a Boy”. And a studio version of “Baby Dont You Do it”. Also, “Mary” and “Greyhound Girl”.

Thanks Luis for that comprehensive listing of The Who “Life House” recordings that eventually appeared on “Odds and Sods” and many B-Sides

and a big Thank You to Sam Sutherland for an exciting recollection of The Who classic LP – this has to be the BEST writing I’ve seen in ages – Bravo Sam!

There are dozens of accounts concerning the track ending. The one I tend to believe about “Baba O’Riley” is that Keith Moon – an accomplished fiddler and violinist, as well as a superbly-talented percussionist – was eager to do the song’s violin outro, and got Shel Talmy to bring in Bobby Graham to play the percussion outro while Moon went orbital with his closing violin outro. Graham and Moon had a friendly but spirited call-and-response at the end, each pushing the other to lose pace. As history has proven, neither one did and the finished product was nothing short of spectacular.

The unfortunate crashing of “Lifehouse” left us with the fortunate best album EVER by The Who! And it also gave a lot of great leftovers, including the stand-alone singles “Join Together” and “The Relay”, as well as some great content for “Odds & Sods” and on the expanded “Who’s Next” released at the end of the ’90s.