“What’s Shakin’”: The LP That Featured Pre-Fame Clapton, Winwood, Butterfield & Spoonful

by Jeff Tamarkin “This was an album that had no organic reason for being. Absolutely none.”—Jac Holzman, Elektra Records president, on the May 1966 compilation LP What’s Shakin’, released by his own label

“This was an album that had no organic reason for being. Absolutely none.”—Jac Holzman, Elektra Records president, on the May 1966 compilation LP What’s Shakin’, released by his own label

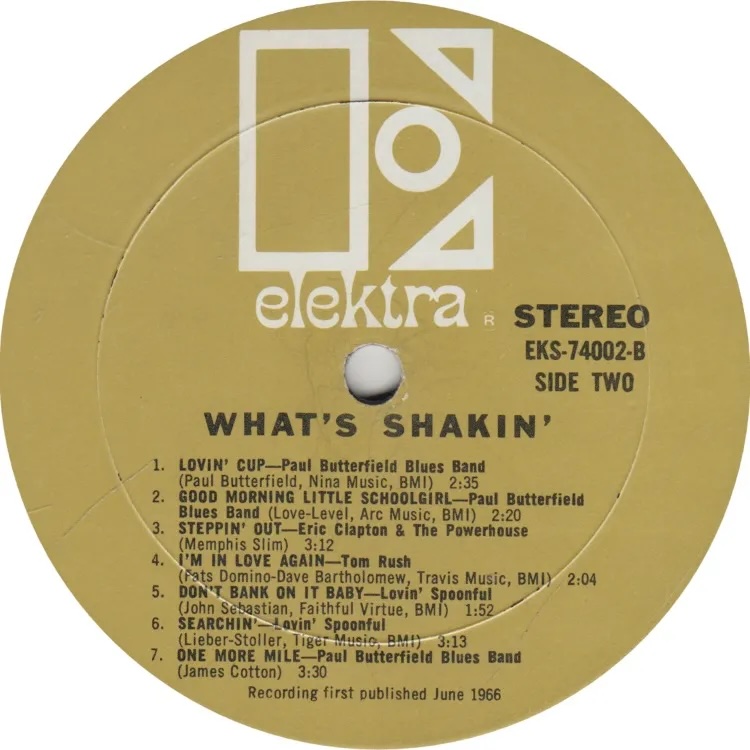

Never has a record company owner been as wrong as Holzman. Although What’s Shakin’, a 14-song collection of odds and ends recorded by various artists, never made the Billboard LPs chart and barely scraped into the bottom rungs of competitors Cash Box and Record World, it offered some of the strongest electric rock of a year swimming in it. None of the music on What’s Shakin’ could be found elsewhere, and for those hip enough to find out about it and dig in, it immediately became gold. Here were five tracks by Elektra’s signature rock act at the time, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band; four by the Lovin’ Spoonful (who’d signed to a different label); and three by a mysterious entity dubbed Eric Clapton and the Powerhouse—whose stunning blues-informed vocals were provided by a just-turned-18 wunderkind named Steve Winwood—that never recorded again.

Add to that a single tune each by New York songwriter/musician Al Kooper (still largely known as the composer of Gary Lewis and the Playboys’ #1 “This Diamond Ring”) and folkie-gone-electric Tom Rush, and the lineup indeed looks pretty solid six decades down the line.

But at the time, to the mainstream rock audience, not so much, and What’s Shakin’ needs to be put into perspective for that to make sense—and to justify Holzman’s seemingly condescending opinion of his own product.

Holzman and co-founder Paul Rickolt had conceived of and launched Elektra Records in 1950, as a label that specialized in folk music—and only folk music—with an early roster encompassing traditionalists Theodore Bikel, Oscar Brand and Jean Ritchie, bluesman Sonny Terry and, later, folk headliners like Judy Collins, Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton. The label enjoyed a stellar reputation but, like so many other players in the increasingly rock-centric music industry of the mid-’60s, found itself in need of an identity shakeup.

Elektra would, in subsequent years (mostly after Holzman sold it to Warner/Atlantic, a major label conglomerate), become massive, its artist lineup extensive and eclectic—from Queen to Linda Ronstadt, Metallica to Jackson Browne, the Cure to Bread to Carly Simon. That ascension would start in earnest with its 1966 signings of local L.A. favorites Love and the Doors, the latter of course emerging as a defining American band of late-’60s rock with its debut album and chart-topping single “Light My Fire.”

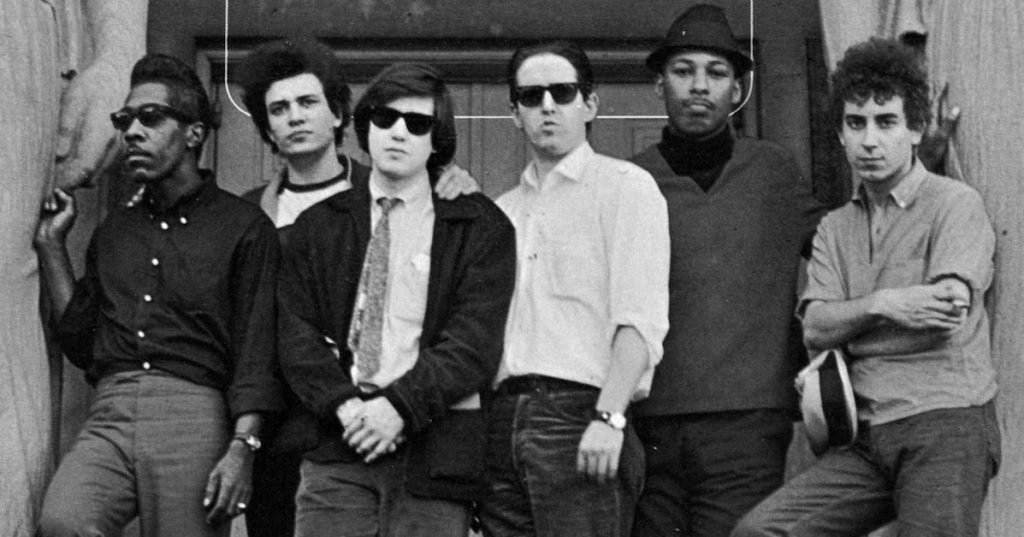

But first there was Butterfield. Led by its namesake vocalist and harmonica whiz Paul Butterfield, and featuring the electric guitar pyrotechnics of Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band was positively revolutionary in its approach, an interracial outfit that knew its way around an electric blues standard but was unafraid to take the music someplace new, incorporating elements of John Coltrane-inspired modal jazz, Indian raga drone and period-perfect, Fillmore-ready psychedelia.

The self-titled debut album by the Butterfield Band had been released in 1965 and while its #123 placement in Billboard didn’t qualify it as a commercial hit, the music’s influence on the developing blues-rock scene of the era was unfathomably huge. Just ask Bob Dylan, who hired Bloomfield, bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay to accompany him when he made his epochal decision to “go electric” at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965.

The PBBB’s debut was still largely true to its inspiration, dominated by covers of blues numbers written by the likes of Elmore James, Willie Dixon and “Little” Walter Jacobs, although three of its 10 tracks were originals contributed by band members and one, the powerful, semi-autobiographical “Born in Chicago,” by friend Nick Gravenites, a singer-songwriter-guitarist who would later make a significant impact in various areas.

By the time the band was ready, in the summer of 1966, to cut its followup, it had moved forward in a big way, however. The title track from East-West was a multi-movement, multi-textured 13-minute landmark that took in the aforementioned jazz and Indian elements, showcased Bloomfield and Bishop’s otherworldly guitar solos and really had little in common with the Chicago blues around which the band had initially coalesced.

But first there was the matter of several leftover tracks from around the time of their sessions for the first album. The band had already attempted cutting a debut album in late 1964, but those tracks were scrapped; the musicians started over again and ultimately came up with the album that established the Butterfield name. (Those 1964 sessions were later released as The Original Lost Elektra Sessions. Three of the songs on that comp also show up on What’s Shakin’, albeit in different recordings.) Four of the PBBB tunes on What’s Shakin’ are covers of classic blues compositions: Willie Dixon’s “Spoonful,” Little Walter’s “Off the Wall,” harmonica master James Cotton’s “One More Mile” and Sonny Boy Williamson I’s “Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl.” The fifth, “Lovin’ Cup,” is credited to Butterfield. Very much in the style of the band’s official debut, the tracks are all solid blues-rockers that showcase the musicians’ superior chops and the band’s total commitment to the form.

Related: Classic albums of 1966

The Lovin’ Spoonful’s involvement is a bit more indirect. By May 1966, when What’s Shakin’ was released, the Spoonful—John Sebastian, Zal Yanovsky, Steve Boone and Joe Butler—was already at the top of the heap of American rock ’n’ roll, having scored top 10 hits with original songs like “Do You Believe in Magic” and “Daydream.” But those, along with all of the Spoonful’s recordings, were issued on the independent Kama Sutra label, not Elektra. The story, as told in writer Richie Unterberger’s liner notes to a What’s Shakin’ reissue, is that the Spoonful had considered signing with Holzman and Elektra, but ultimately rejected that offer in favor of the lesser known label’s.

As a consolation prize of sorts, the Spoonful agreed to donate four tracks—their earliest studio recordings, predating the Kama Sutra association—to the compilation, two of which, Chuck Berry’s “Almost Grown” and Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller’s “Searchin’,” a hit for the Coasters, were covers while the other two, “Don’t Bank on It Baby” and “Good Time Music,” were Sebastian originals. The first three of those displayed an allegiance to classic R&B/early rock while “Good Time Music,” in particular, was more in line with the folk-rock/electric jugband sound the band was developing. In fact, “Good Time Music” would become something of an anthem for the band’s overall approach. (And, for what it’s worth, a cover of the song by Americans the Beau Brummels reached #97 in Billboard.)

As for the three tracks credited to Eric Clapton and the Powerhouse, even the most avid fan of Slowhand can be forgiven for a little head scratching. Essentially, there was no such band, at least not one that ever performed live or recorded a full album. What you hear on What’s Shakin’ is what you get from this studio-created concoction. And what a concoction it was, assembled in March ’66 by Elektra producer Joe Boyd (an American working in London) for the exclusive purpose of contributing to this album: Guitarist Clapton, who had recently left John Mayall’s Blues Breakers and had not yet co-founded Cream, was joined here by young Steve Winwood (still known in the business as Stevie, but credited here as Steve Anglo or Stevie D’Angelo for contractual reasons, as per Unterberger’s notes), then serving as the lead singer with the Spencer Davis Group, whose “Gimme Some Lovin’” breakthrough would not be released in America until early 1967; bassist Jack Bruce, then with Manfred Mann and also headed soon for Cream; vocalist/harmonica player Paul Jones (also of Manfred Mann); little known pianist Ben Palmer and drummer Pete York, another Spencer Davis Group mainstay.

Both Winwood and Clapton are uniformly superb on the three tracks: Robert Johnson’s “Crossroads,” which would soon become a Cream showcase piece; the Memphis Slim blues instrumental “Steppin’ Out” (which Clapton had recorded with Mayall and would continue to perform with Cream) and “I Want to Know,” an original written by Jones but credited to “MacLeod,” which happened to be the surname of Jones’ wife. Eric Clapton and the Powerhouse’s three contributions to What’s Shakin’ remain the only music ever released under that name. Clapton has said that a fourth track was recorded, but it seems to have been lost to the ages.

That leaves two further cuts: one each by Al Kooper and Tom Rush. Kooper, by 1966, was ensconced in the Blues Project, a band plowing similar territory to Butterfield: blues-rock that had greater ambitions. “Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes,” although credited on What’s Shakin’ to Kooper, was actually derived from a 1928 Blind Willie Johnson song, “Lord I Just Can’t Keep From Crying,” and would also appear, in a much harder arrangement, opening the Project’s sophomore album, Projections, where it was slightly retitled as “I Can’t Keep From Crying.” The What’s Shakin’ version, in fact, utilized the accompaniment of two members of the Blues Project, bassist Andy Kulberg and drummer Roy Blumenfeld, augmenting Kooper’s guitar, keyboards and vocal, and although the easygoing take on What’s Shakin’ is likable enough, there’s little denying that the Projections rendition benefitted from the searing, stinging lead guitar work of Danny Kalb, who turned the song into a raveup that gave notice that this album was one that would be savored by many for decades to come.

Finally, there’s Rush, who offered his own good-time track, a cover of Fats Domino and Dave Bartholomew’s “I’m in Love Again.” Rush had launched his career as a pure folkie, but like many of that ilk, by 1965-66 he had discovered electricity. While his cover of the R&B classic is hardly on the level of Dylan’s recordings of the day, the outtake from his 1966 album Take a Little Walk with Me, which featured (like Dylan’s Bringing it All Back Home) one side of acoustic music and one electric, and also boasted Kooper involvement (in fact, the latter’s tune may have been recorded during the Rush sessions), is certainly worthy of inclusion on this remarkable compilation.

So why, then, if What’s Shakin’ is such a killer collection packed with rarities, did Jac Holzman later dismiss it, even stating (in Unterberger’s liners), “I think people were reserving their money for the really good things. And [What’s Shakin’] was okay. It’s not stellar”?

Likely, as the owner of the label that released it, his negative opinion was based on the album’s meager initial sales. Although What’s Shakin’ received a handful of positive reviews, there wasn’t much of a rock press yet in 1966 to give it the boost it deserved. Similarly, FM rock radio was in its infancy, and although some tracks may have received airplay, this music was too off-center to resonate with programmers who could relate to a band’s new album but didn’t quite know what to do with a compendium of oddball random tracks from artists that were not quite (yet) in the mainstream.

In later decades, the album would come to be appreciated more than it was during its own time; several “Best Albums of All-Time” lists have even included it. But for the most part, it remains—and probably always will—a footnote to a heady era when musicians were enjoying newfound freedoms and were still discovering who they were and what they could do when they let their creative instincts guide them.

Listen to the opening track on What’s Shakin’, the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Good Time Music”

Though it’s long out-of-print, you might be able to find a used copy in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversation“There wasn’t much of a rock press yet in 1966.” The only serious rock press in the mainstream media that I knew about at the time was the record reviews in the back of Hit Parader magazine.

Of course, fanzines like Paul Williams’ Crawdaddy and David Harris and Greg Shaw’s Mojo Navigator were where the serious “seriousization” [sic] [I hope] of rock music was happening.

By 1966, I had discovered comic book fanzines and had received or ordered copies of the Rocket’s Blast Comic Collector, Wally Wood’s Witzend, and Bill Spicer’s Fantasy Illustrated.

How I remained oblivious to rock & roll fanzines back then still puzzles me.

PS: I could never prove this, but I’d bet you a French Pastry to a Dunkin’ Donut, that the vast majority of people who bought What’s Shakin’ in 1966-1967 were white, teenage males who didn’t play high school sports and didn’t have many girlfriends (if they’d ever had one at all).

Out of print?! Uh, would someone please call Jack Holzman and request a half-speed master pressing and CD? The timing seems perfect enough to me!

Thank you Jeff for this interesting story about this album. I found it in a used vinal store and bought it due to the list of artists. This in depth background story, really makes me appreciate it even more.

I was already a fan of the Spencer Davis Group,, Al Kooper, Lovin’ Spoonful & PBBB. These songs were like undiscovered musical treasures.

This version of the Al Kooper song is interesting as I had only heard the song by the Blues Project.

I agree with you 100%, if you’re a fan of of any of these bands, you will enjoy this album.