Thin Lizzy ‘Live and Dangerous’: When Anything Might Happen—And Did

by Colin Fleming Readers of rock and roll interviews are well-versed in band members speaking of their desire to translate the energy of their live show to the studio setting. They talk of a fundamental, conceptual disconnect. How to make the round peg go into the square hole?

Readers of rock and roll interviews are well-versed in band members speaking of their desire to translate the energy of their live show to the studio setting. They talk of a fundamental, conceptual disconnect. How to make the round peg go into the square hole?

Certain groups, like the Who, keep chasing that would-be in-house energy, as it were, transmogrifying those pent-up, adrenalized forces into rangier efforts of creativity. Hence, “A Quick One (While He’s Away),” The Who Sell Out and Tommy—and then coming to, as though by the favors of fortune—the wailing, on-stage aggro-majesty of a Live at Leeds. Other bands talk of making their debut record a live disc—including the Beatles and George Martin, who mulled the possibility of a session at the Cavern—but outside of the Yardbirds, few really seem to do it.

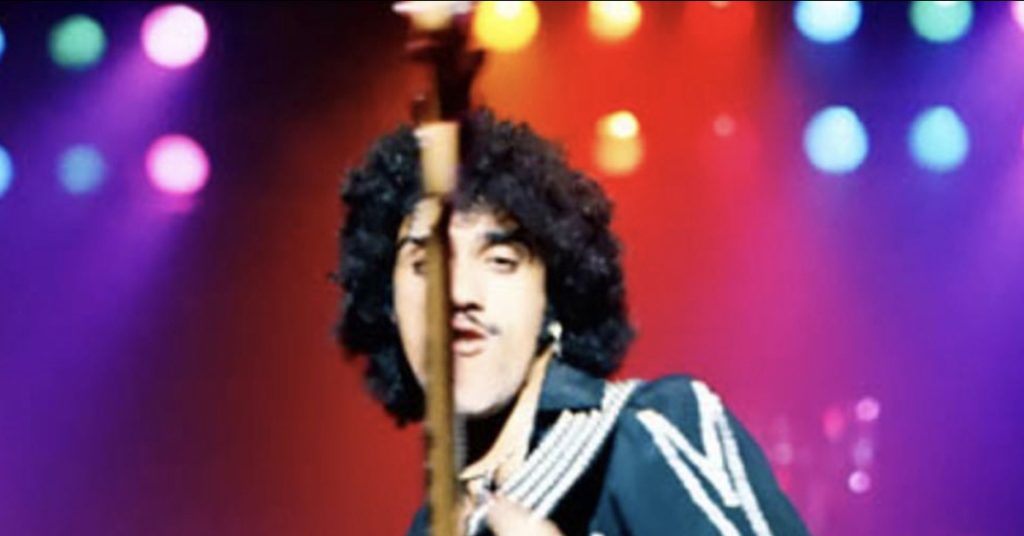

Irish rockers Thin Lizzy were humming along in a career that had seen them release nine studio albums through the late summer of 1977. Among these was their commercial breakthrough, Jailbreak, from spring 1976. Thin Lizzy, in the studio, bustled. Bassist and lead singer Phil Lynott wrote the sharp-edged songs, and the band’s co-lead guitarists Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson helped those songs make the most of their sonic possibilities. Their lines were exacting, full of finesse and fire, with a clean, articulate tunefulness that created blazing, dual-riff, well-spoken, threnodies.

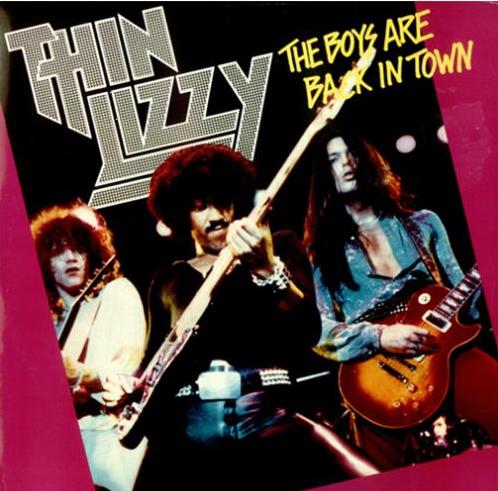

A song like “The Boys Are Back in Town” could be stripped of all parts save its guitar tracks, and would still register as memorable, albeit in a much different key than the one to which we’re so accustomed thanks to the accrued decades of radio play.

And yet, the band still had a sense of chasing a sound in the much more “official” environment of the studio than what it was accustomed to on stage. Most live albums aren’t intended as artistic statements. Something as rightfully vaunted as Live at Leeds was meant to be a placeholder, a means to put some product on the shelves while Pete Townshend figured out next moves post-Tommy. Leeds may be the best album the Who ever made. It may be the best rock and roll album ever made, which is a conversation for a different day. But it’s tough to argue that Thin Lizzy ever made a better album than what ended up being LP number 10.

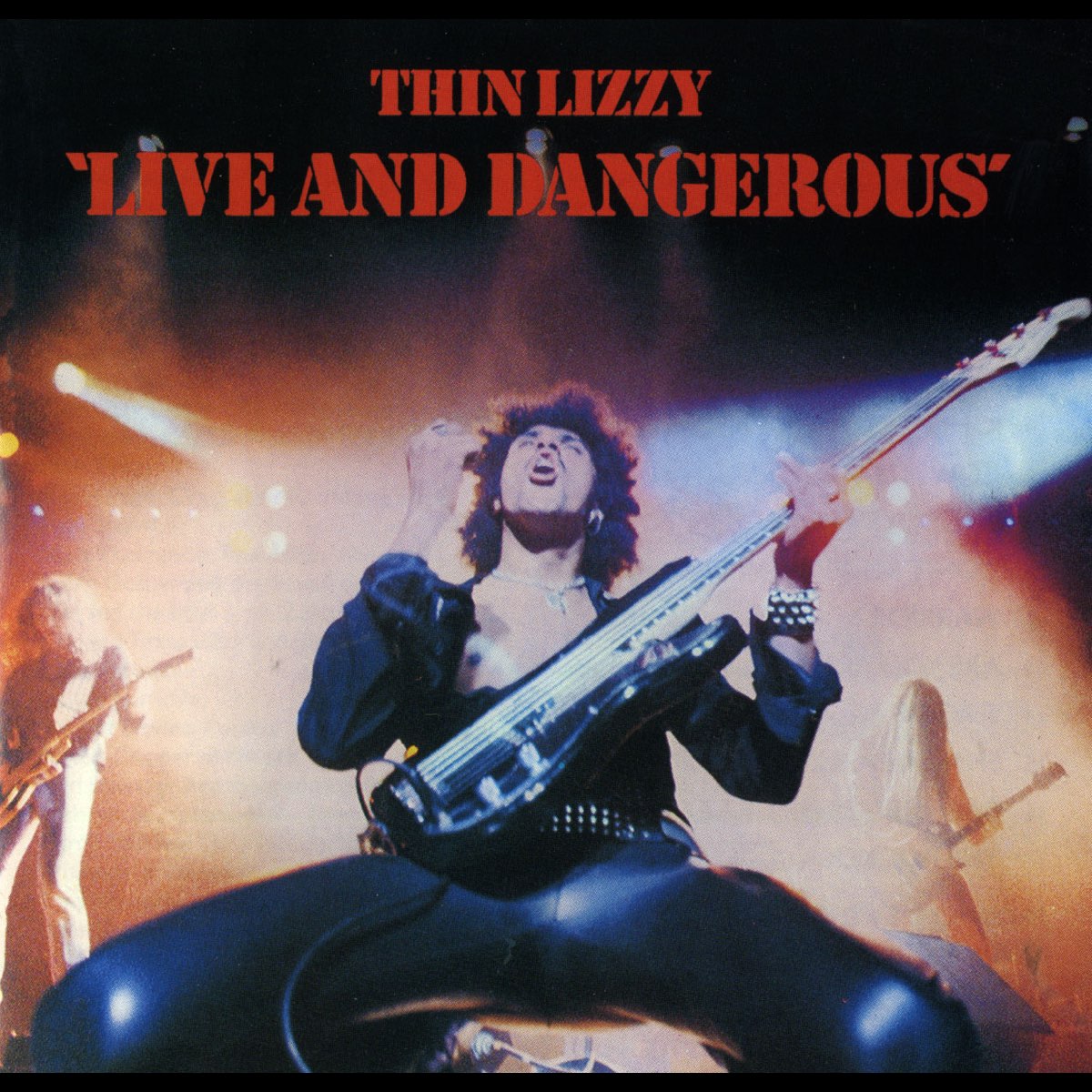

They called the set Live and Dangerous, and well they should. There’s a heightened sense of expectancy with a live show, which may be diminished in the days of highly polished, slick, low-risk performances, with the same setlist night after night, but one still has the feeling—or perhaps it’s a hope—that anything may happen.

Lovers of live albums seem to “get it”—the power of what music can do, how it’s able to surprise us—in ways that others don’t. Someone who is a greatest hits person is going to be a lot different than a “Yes! The Replacements officially released that dodgy bootleg tape!” person, aren’t they?

Thin Lizzy could light it up in the studio, but they scorched on the stage. They brought the good kind of danger. The thrills, the balls, the gusto, the going-for-it quality of head-out-the-window rock and roll.

Released on June 2, 1978, Live and Dangerous was a double album in a decade thick with them. If you didn’t have a double live album in the 1970s were you still a hard rock band or were you Bread? These sorts of albums were akin to a mechanized army. You got the guitar solos, you got the drum solos, you got bloated versions of the hits and shouts to get those hands in the air. What you didn’t get were many albums that will be worth hearing for as long as people have ears, which is exactly what Live and Dangerous is.

Thin Lizzy and producer Tony Visconti combed through 30 hours of tapes in the assemblage of Live and Dangerous, but a core group of shows lit the (composited/overlaid) path: a London Hammersmith Odeon gig from November 14, 1976, two from Philly on October 21 and 22 of 1977, and another from Toronto on the 28th of that same month.

When you make a live album, you can cherry-pick from the archive, put out the whole of a single show, a portion of a show, or do what Thin Lizzy did on Live and Dangerous, if you’re able—make parts of multiple shows come together as if they were instead the night of nights.

Live and Dangerous runs nearly 80 minutes in duration, but like the best versions of the Grateful Dead’s “Dark Star,” you listen to the work in its entirety and then do a double-take when you see the clock because it feels like no time at all has passed.

If you wanted to suggest that each song on Live and Dangerous—and we’re talking Lizzy classics like “The Boys Are Back in Town,” “Dancing in the Moonlight (It’s Caught Me in Its Spotlight)” and “Johnny the Fox Meets Jimmy the Weed”—are definitive (as impressive and foundational as their studio counterparts are), you won’t encounter much pushback from the seasoned listener.

Related: The story behind “The Boys Are Back in Town”

The knock with the album is that it was doctored in the studio and is a veritable overdub fest. Accounts from those who were there differ. Does it matter? The record is the statement, and the statement is formidable. You’ll never think any aspect of it isn’t live when you listen, and there’s no denying the record’s energy. It keeps coming at you in waves.

Ever watch a film and as you’re doing so you make a mental list of your favorite parts, changing the order as the movie goes along? Live and Dangerous is the in-concert LP version of that. What registers as a peak is quickly revealed to be but another high point which itself has another above it: a ceiling-less offering of hard rock grandeur.

“Jailbreak” makes for the ideal opener, a statement of liberation, of the finding—and the letting loose—of the power the band had been looking for in the studio. This is us, the record seems to say, from its first galvanizing notes; the call to arms, the call to action. Stand and deliver? Check.

The best live albums—at least in rock and roll—feel as if they take a toll on us while we listen to them. Almost like we’ve undertaken a workout. Leeds, Sam Cooke’s Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, Dylan in Manchester in 1966, Elvis Presley in the round for his Comeback Special.

Live and Dangerous hits us again and again, and we like it. At its close, you feel like you should take a breather. The two-guitar attack makes this one of those guitar albums that every fretboard fanatic must own, but the guitars are so lyrical that it’s as if they’re singing along with Lynott. Think of them as shredding choristers.

An 2023 expanded, but limited edition of Thin Lizzy – Live and Dangerous is sadly already out-of-print.

The full cache of Live and Dangerous-related shows was released in a 2023 mega-boxed set that is equally worth one’s time and devotion [if you can find it; it was a quick sell-out], but the mission-statement-delivered/mission-statement-fulfilled focus of the original album itself has that tearaway quality—in dual-guitar spades—that all the best rock and roll possesses. The bad kind of danger, as such, is in missing out, so don’t.

Their recordings, with many collections including a 2025 acoustic set, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Video: Watch Thin Lizzy perform “Don’t Believe a Word” on The Midnight Special in 1977, the same year as the Live and Dangerous release

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.