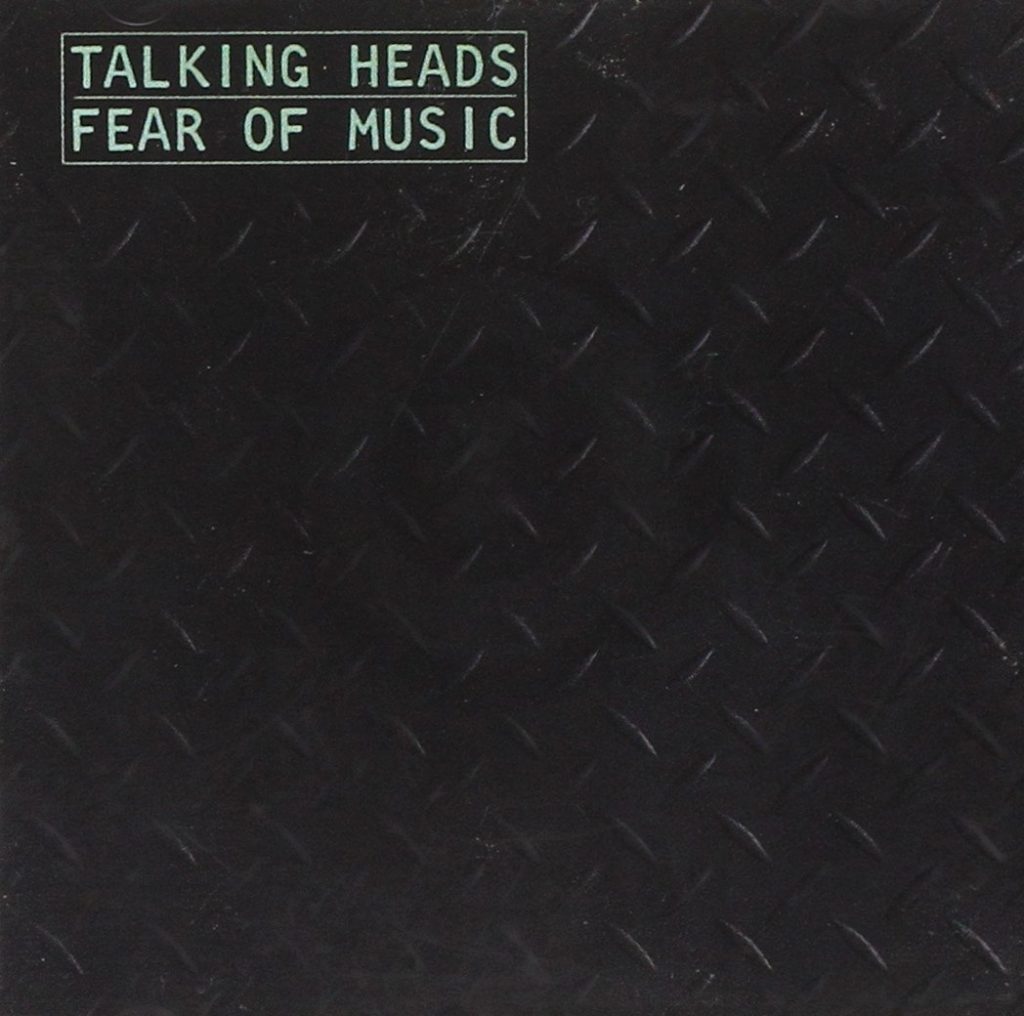

By now, it’s almost a cliche to call 1979’s Fear of Music, Talking Heads’ third album, transitional. A quick Google search for <“Fear of Music” “Talking Heads” “transitional”> yields more than 7,000 hits (And yes, I’m aware of the irony that a world where you can search for anything immediately is a world that Fear of Music fears.) Of course, cliches become cliches by being true—it’s when they are worn by overuse, becoming a lazy writer’s way of actually doing work, that they turn dangerous.

By now, it’s almost a cliche to call 1979’s Fear of Music, Talking Heads’ third album, transitional. A quick Google search for <“Fear of Music” “Talking Heads” “transitional”> yields more than 7,000 hits (And yes, I’m aware of the irony that a world where you can search for anything immediately is a world that Fear of Music fears.) Of course, cliches become cliches by being true—it’s when they are worn by overuse, becoming a lazy writer’s way of actually doing work, that they turn dangerous.

In Fear of Music’s case, the question often unanswered is transitioning from what to what. The easy answer is that Talking Heads’ music was moving from the tinker-toy minimalist art trio that captured the hearts of CBGB to the slinky, extended Afro-funk ensemble that became superstars. True, but facile. But the idea of what Talking Heads were was also changing.

Four years removed from their formation, when they lived together in a loft on Chrystie Street, wore monochrome clothes and got haircuts at the same time—“so no one becomes a rock star,” bassist Tina Weymouth told me when I interviewed them on WNYU-FM in 1976. In that same interview, Tina passed on a piece of advice they received from Lou Reed: a band is like a fist, and labels, managers, producers, etc., want to pry open that fist, and make it easier to crack off one of the fingers and make them a star. Fear of Music, which arrived on August 3, 1979 and peaked at #21 in Billboard, is the record on which it feels they had forgotten Reed’s advice. It’s the first step in David Byrne’s assumption of power, moving Talking Heads from a band to his band.

Not uncoincidentally, it was also the first album not drawn from the band’s CBGB repertoire, and the first on which Brian Eno was essentially a member of the band. Pointedly, Byrne and Eno would go to work on their own project, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, before rejoining the the band for the Heads’ next album, Remain in Light.

In a way, it allowed the band to sidestep the problem of how to follow-up on “Take Me to the River,” an Al Green cover that reached #26 on the Billboard singles chart. And nearly everything about Fear of Music feels engineered to deflect your interest. It gives you no time to get your bearings. The opener, “I Zimbra,” is a series of nonsense syllables by Dadaist poet Hugo Ball, chanted over a single-chord vamp, the guitars, basses, drums and percussion chattering back and forth at each other, changing shapes and stressed beats, speaking in a code as indecipherable as the lyrics.

Even the cover, black matte paper and embossed in the design used on the street-level metal doors that covered the entrances to New York City basements, gave the impression of something coming from underground. And it certainly sounded like nothing else. Hearing it today, the album’s mix of Motorik and Afrobeat sounds inevitable; in 1979 it was dance music that reflected the time: twitchy, nervous, unsure of the next step.

Fear of Music is an album full of warnings: In nearly every song, Byrne breaks into the songs to deliver the bad news. “Don’t look so disappointed. It isn’t what you hoped for, is it?” he sings in the Bowie-esque “Memories Can’t Wait.”

“Never listen to electric guitar,” he demands in “Electric Guitar,” it’s “a crime against the state.” Even the most benign subjects are fraught with worry: “Air,” he sings, “can hurt you too,” while not even his own thoughts are safe.

“Everything seems to be up in the air at this time,” he frets in “Mind.” The album’s sense of sensory overload, the idea that Heaven is a place “where nothing ever happens,” is prescient, especially given that CNN is a year away, the internet bubble almost 20. But when the band decided to hold the album’s release party at the Mudd Club, dancing to “Life During Wartime” (with its famous “This ain’t no party, this ain’t no disco” refrain) you could think of yourself as very meta.

Fear of Music’s closest analog might be Radiohead’s OK Computer, also a third album, that saw them step away from being a big, post-Nirvana guitar band to something infinitely stranger and richer. While many see these albums as masterpieces, and some even wish they had stayed there, for both bands the albums are landing zones, a stretching of ambitions, gambles that would pay off grandly in the future.

Watch Byrne perform “I Zimbra” in 2021 on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert to promote his American Utopia on Broadway production

Related: 1979 – The year in 50 classic rock albums

You can find the album, and others in Talking Heads’ great catalog, in the U.S. here and in the U.S. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI saw this tour, they had B-52’s opening, quite a show. This is an interesting look at the album, it was never a favorite, but its role in the band’s development is significant. Thanks for addressing it.

IMO it’s their best album and probably my favorite as well. Very dark album, to be sure.