When he turned 25 on January 3, 1970, Stephen Stills had much to celebrate. His partnership with David Crosby and Graham Nash had been hailed as a supergroup, thanks to their band priors, signature vocal blend, and Stills’ instrumental versatility, propelling Crosby, Stills and Nash’s self-titled debut to critical and commercial success soon after its May 1969 release. With Stills’ former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Neil Young joining them for their first tour two days before their historic appearance at Woodstock, the band’s prospects brightened even further.

When he turned 25 on January 3, 1970, Stephen Stills had much to celebrate. His partnership with David Crosby and Graham Nash had been hailed as a supergroup, thanks to their band priors, signature vocal blend, and Stills’ instrumental versatility, propelling Crosby, Stills and Nash’s self-titled debut to critical and commercial success soon after its May 1969 release. With Stills’ former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Neil Young joining them for their first tour two days before their historic appearance at Woodstock, the band’s prospects brightened even further.

That January also saw the expanded band finishing its tour with concerts in London, Stockholm and Copenhagen, and a completed mixdown for their first album as a four-way juggernaut, Déjà Vu, was slated for release in March. After 39 concerts across the U.S. and Europe, the principals took advantage of the break to catch their collective breath after a meteoric launch, with Atlantic Records’ co-founder and chief Ahmet Ertegun persuading Stills to stay in England, where he retreated to Brookfields, the Surrey, England, mansion whose previous owners had been Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr. That Ertegun nudged Stills to delay his return to California signaled Ertegun’s recognition that Atlantic’s second supergroup was proving as contentious as its first, Cream, and that calling a time out could ease tensions. Ertegun knew firsthand how the volatile relationship between the two Buffalo Springfield alumni had undermined that influential folk-rock band, and undoubtedly wanted to protect his investment in CSN&Y.

Between his obsessive dominance during the Crosby, Stills and Nash sessions, the learning curve for the expanded band on the concert trail, and renewed pressure as they recorded Déjà Vu, Stills often found himself at odds with his bandmates. Accolades and upward mobility that would reinforce the fellowship for a new band was offset by the four frontmen’s individual egos, with high living offstage adding a divisive centrifugal spin. Crosby and Stills had already been dubbed the “Frozen Noses” in recognition of their fondness for cocaine, a stimulant not known for breeding contentment.

It’s also fair to survey the musical landscape in 1970, a watershed year mirroring rock’s creative and commercial ascent. Pathfinding bands that had emerged in the 1960s were splintering into new configurations and solo careers, none more influential than the Beatles, whose members all released solo albums that year. Crosby, Stills and Nash envisioned their collaboration as an open marriage with room for outside ventures, and Neil Young had already released two solo albums before joining them. That Stills would begin work on his debut that same January with initial sessions at Island Records’ London studios was inevitable.

Then manager David Geffen would later remark that Stephen Stills had regarded the supergroup as “his band,” rather than the democracy the others desired, making his subsequent solo sessions a welcomed chance to flex his control unchallenged. Free to multi-task on guitars, keyboards, bass and percussion, and try his hand at horn and string arrangements, Stills also leveraged his elevated stature as gilded rock star to draw from an impressive cast of musical guests, including Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Starr, Booker T. Jones, John Sebastian, Cass Elliot and arranger Arif Mardin.

That balance of DIY proficiency and top-tier talent animates the album’s lead-off track and biggest hit, “Love the One You’re With,” which would go on to reach #10 on Record World’s singles chart and top 20 success on two other U.S. singles charts. With its buoyant, syncopated rhythms, the arrangement draws from Stills’ familiarity with Latin and Caribbean styles, absorbed during a nomadic upbringing as his military family moved along the Gulf Coast and down to Central America, heard here in simmering percussion and Stills’ evocative steel drum accents. Layering Hammond organ beneath driving acoustic rhythm guitar, Stills is backed by choral harmonies from Crosby, Nash, Sebastian (who had deflected an invitation to join Crosby, Stills and Nash at their inception), Rita Coolidge and her sister Priscilla, then married to Booker T. Jones.

By expanding the vocal backdrop to a mixed chorus, Stills effectively retains a core CSN strength while subtly differentiating his solo sound. While the blend of male and female voices invites comparison to contemporary work by Delaney and Bonnie, Joe Cocker, Leon Russell and Eric Clapton, the tactic also harkens to Stills’ pre-rock apprenticeship (alongside future Buffalo Springfield partner Richie Furay) in the Au Go Go Singers, who followed a familiar commercial folk template shared with the New Christy Minstrels, the Serendipity Singers and other clean-cut hootenanny regulars.

In its enthusiastic endorsement of casual sex, “Love the One You’re With” was on trend in an era of sexual liberation untouched by the future specter of AIDS. Coincidentally, it resonated with a romantic triangle between Stills, Graham Nash and Rita Coolidge, who Stills had courted when he intercepted her phone call to Nash. Ever the hopeful romantic, Stills penned another album track, “Cherokee,” in her honor, although Coolidge broke off the affair and hooked up with Nash after learning how Stills had blindsided his bandmate in his pursuit.

The album follows its opener’s partying fervor with “Do for the Others,” an acoustic ballad that mines emotional turf that would prove familiar across Stills’ solo and group contributions, steeped in romantic mourning that borders on self-pity, followed by “Church (Part of Someone),” a piano-driven pop gospel exercise that proves nearly as heavy-handed as its title. Both songs reflect their author’s prowess as a musician and producer while betraying his liabilities as a lyricist, especially when reaching for earnest expressions of emotion while lapsing into stylistic cliché.

More successful is “Sit Yourself Down,” the side two opener that would serve as the album’s second seven-inch release. Gospel once again provides its stylistic denominator, but here Stills harnesses its meditative lyrics to a more energetic mid-tempo arrangement that brightens during its choruses, accentuated by double-time percussion and Stills’ electric guitar punctuation. Evidently written while his romance with Rita Coolidge had yet to cool, the song’s all-star backing chorus buttresses Crosby, Stills and Nash with Coolidge, John Sebastian and Cass Elliot, whose warm vocal blend compensate for the unintentional comedy of the lyrics: when Stills muses how he needs to “quit this runnin’ around” and find “a patch of ground” to escape the blues, the knowledge that he was cavorting with his “Raven” at his English manor when he wasn’t hitting London’s clubs with new pal Jimi Hendrix.

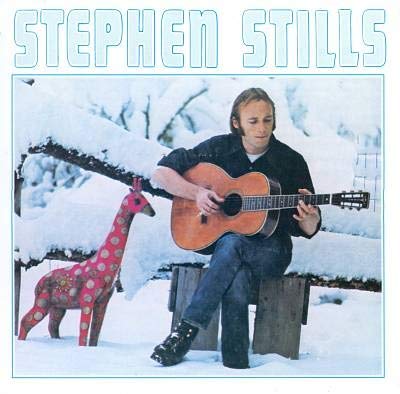

Hendrix himself figures prominently in one of the album’s brightest spots, “Old Times Good Times,” a fleet rocker elevated by his rippling, squealing solos, wisely given ample room by Stills, who leans more forcefully into florid Hammond B-3 organ arpeggios and dense chords. Stills, who later claimed he “learned to play lead guitar from Jimi” despite the evidence of his Buffalo Springfield, CSN and “Super Session” playing, would be devastated by news of Hendrix’s death two months before Stephen Stills was released on November 16, 1970, (with its U.K. release arriving on what would have been Hendrix’s 28th birthday).

Further testimony to Stills’ ascendance to A-list status follows with another hallowed six-string guest, marking the only time Eric Clapton would appear on the same album as Hendrix, whose 1966 arrival in London famously jolted the British guitar god. Clapton had visited Stills in the studio, where the two jammed at length on the Champs’ “Tequila” before Clapton added his solo to the stalking blues vamp of Stills’ “Go Back Home,” executed in a single take to complement Stills’ own squalling wah-wah guitar figures. The caliber of instrumental playing once more triumphs over otherwise pedestrian lyrics that retread shopworn blues tropes.

Between sessions in London and Los Angeles, and its blue-chip supporting cast, Stephen Stills wore its superstar aspirations openly, reaping career-best sales. Boosted by the halo effect of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and top 20 single success for “Love the One You’re With,” Stills held bragging rights for the most successful of the quartet’s solo albums released during ’70 and ’71. Over time, however, its uneven material would be eclipsed by the enduring cult mystique of Crosby’s If I Could Only Remember My Name and the even longer shadow cast by Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush.

[Stills’ mighty catalog is available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.]

Bonus Video: Watch Stills perform the album’s “Black Queen” in 1972

Related: Our Album Rewind of Stills’ Manassas

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationTerrific article. Great album. Wasn’t 1970 a good year for rock; Deep Purple In Rock, Allman Brothers Band – Idlewild South, Van Morrison – Moondance, Atomic Rooster – Death Walks Behind You, Free – Fire & Water etc. In my opinion Stills sounds best with minimal production. My favourite track on the album is Black Queen. Stills raspy expressive vocal alone with his unique sounding acoustic guitar. The backing vocals are a bit overdown with the additional singers and also some of the horn arrangements are a bit intrusive on the last couple of songs. Otherwise a strong debut. The other two from CSN also came out with strong debut solo albums with Young releasing his third album, arguably his best – After the Goldrush. Stills continued to release quality solo albums, along with 2 Manassas group albums, until the mid 70’s. Unfortunately his muse started to dry up towards the end of 70’s along with his deteriorating voice. Crosby & Nash couldn’t match the quality of their debut albums as the 70’s progressed. Although Young’s genre swapping career has been patchy he was able to produce several top notch albums in the following decades.

Nicely done. An early favorite of mine, but you’re criticisms land well. Good history, too. Thanks!

A somewhat unnecessarily critical review. Seems the reviewer doesn’t like Stills’ lyrics. Imho a brilliant album from start to finish that has stood the test of time very well. (That’s of course a subjective view just as the review is. Nothing more nothing less).

Yup, yup, and yup. Especially your ending statement about Crosby and Young.