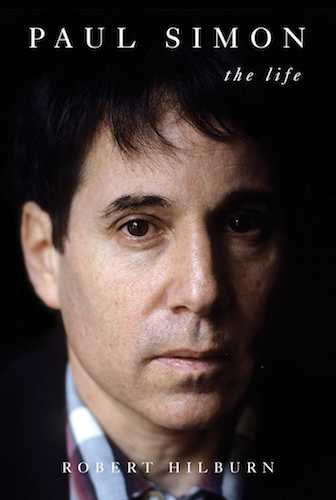

Paul Simon: The Life, the 2018 biography written by longtime Los Angeles Times music journalist Robert Hilburn, is the first on the singer-songwriter for which the artist sat down for extensive interviews. In this first half of a two-part interview, Hilburn discusses his working relationship with Paul Simon during the creation of the book, and his reasons for writing the bio.

Best Classic Bands: Paul Simon’s life story has been well chronicled. Why did you feel there was more to be said about him?

Robert Hilburn: I was surprised by how little of Paul’s story had been told. Despite numerous biographies (of Simon & Garfunkel and Paul himself), I found them—probably because of Paul’s lack of participation—to present a picture that was both contradictory and incomplete, especially when it came to the music and artistry.

On the positive side, I was drawn to Paul’s story because I loved, during my years at the Los Angeles Times, songwriting, both the stories behind various songs and the creative process. So, I wanted to write in detail about a great songwriter who was open and articulate when talking about the music and the process. At the paper, I interviewed Paul several times and found him endlessly fascinating when talking about music. I also was drawn to him because most of the great songwriters from the 1960s and early 1970s have, for various reasons, experienced sharp declines in the quality and quantity of their work. Paul’s work, from “The Sound of Silence” to Stranger to Stranger, has continued at the highest level.

My goal was to write Paul’s life story, but also explore this subtheme: Where does true artistry come from and how, once achieved, do you protect it against such distractions as fame, wealth, drugs, marriage, divorce, laziness, changes in public taste and fear of failure? For help with the subtheme, I spoke with many outstanding producers, notably Quincy Jones and Allen Toussaint, to get their ideas about artistry and how it is achieved, and they gave me a road map, if you will, as I began questioning Paul.

What was the biggest new revelation or surprise?

There were lots of surprises, but the thing, in retrospect, that surprised me most, perhaps, was that Paul—who seemed to write songs so beautifully and effortlessly—was not a born songwriter. In fact, he spent five years after high school in the lower rungs of the New York City record business, writing songs, recording demos, trying to get his own records released—and all he was really doing was copying the most generic pop-rock on the radio. There wasn’t even a glimmer of artistry or even promise in all those recordings. To show you how corny some of the stuff was, there was a big Connie Francis hit in the 1950s called “Lipstick on Your Collar” and Paul did a demo of an answer song called “I Want to Be the Lipstick on Your Lips.” To my mind, one of the key parts of the book is examining how he ever went from that crap to “The Sound of Silence,” and—with Quincy’s and Allen’s roadmap—I found some specific things that led to that remarkable transition.

Watch Paul Simon sing “The Sound of Silence” solo

Unlike all previous Simon bios, you had his cooperation. What was it like working with him directly?

I found it frustrating at first because Paul, like most great songwriters, is so focused on his new music that he doesn’t really want to talk about anything else—not just his private life, but his early music. I spent many afternoons in his recording studio in Connecticut, trying to get him to focus on the old days, and he’d always say, “Enough of this, let’s listen to some of the new music.” It took several months before he began opening up on his life and his earlier music with the same passion and depth that he addressed the new music. But once that happened, it was thrilling to step inside his head.

With Simon’s long-noted resistance to speaking with biographers, why do you think he changed his mind for you?

I think he was at a place in his life where it made more sense to him, but he was still reluctant. I spent several hours with him talking about the kind of book I wanted to write and why I thought he owed it to history to speak about his life. But it wasn’t until after he read [my] Johnny Cash book that he finally agreed to sit down for a generous series of interviews. I think the talk and the book showed I was interested in writing a serious book, not just a celebrity music book. The thing about so many music biographies is how little time they spend on the artistry and the creative process.

How were you able to get Peggy Harper, Paul’s first wife, to talk on the record?

I got Peggy’s email address from Mort Lewis, who was her first husband and the manager of Simon & Garfunkel. He’s a great guy. I went to his place in Connecticut three times to interview him. He gave me Peggy’s email address and I explained to her I was doing the book and had Paul’s blessings. As I recall, she wanted to think about it; after all, she had never spoken publicly about their relationship. But she eventually emailed me back and said fine. I spent seven hours with her at her home in Tennessee and, for all her privacy, she didn’t seem at all guarded. She was delightfully open and helpful.

Simon has a reputation of being cantankerous, belligerent or unpleasant. Did you find him that way?

A funny thing Paul told me was that when he met Edie Brickell, his [current] wife, one of the first things she said to him was something like, “I heard you weren’t a nice guy.” He was very aware he had a reputation in the 1960s and 1970s, especially, of having a prickly nature. And a lot of that, I think, came from two things. He was so obsessed with the music and so ready to defend it against anyone who tried to change it that he was off-putting to many people who came into casual contact with him.

One thing was his bluntness, which came from his father. Paul’s father was a professional musician who spoke very bluntly to Paul. He didn’t try to sugarcoat it when teenage Paul brought him new songs. He’d say things like, “Paul, you don’t get an A for effort. You have to do better.” He also told Paul, “You have to keep working on your music. You can never master it; you have to keep getting better.” And that stuck with Paul. He was far more interested in getting better than being diplomatic, say, in the studio. Plus, he was sensitive about his size. He was short and felt he had to defend himself against those people who thought they could bully him.

I heard about Paul’s reputation in the 1970s, but I didn’t find him cold or rude when I interviewed him for the paper, and I didn’t sense it in him in the hours that I spent interviewing him for the book. He was blunt. I was surprised once when he said, “I don’t think that’s a very interesting question. Why don’t you ask something else?” I had never heard that from an interview subject before, but it wasn’t meant as nasty. It was his way of trying to get to something more interesting to talk about. But Paul was also a much different person after Graceland.

That album gave him a confidence that made him a much warmer person, and Edie did a lot to bring balance and calmness into his life. Ultimately, I found Paul to be an engaging guy, great sense of humor and very caring. This was also the view of Paul that I heard over and over when interviewing people who have known or worked with him for years. I liked him immensely.

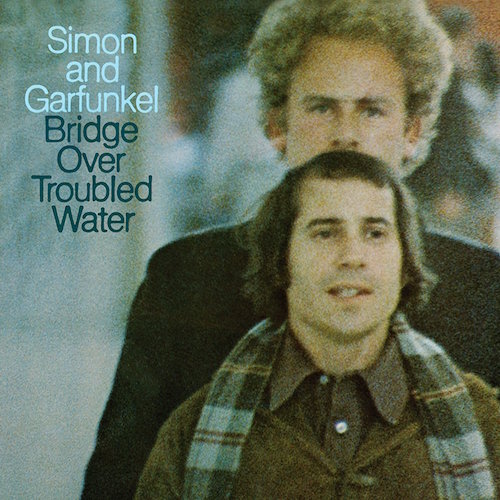

Although Simon and Garfunkel really didn’t last very long as an entity, that relatively brief collaboration has hovered over Simon’s life and art for half a century now. Was it difficult for you to keep that outsized part of the story in perspective, especially considering the strained relationship between the pair that has persisted to this day?

Although Simon and Garfunkel really didn’t last very long as an entity, that relatively brief collaboration has hovered over Simon’s life and art for half a century now. Was it difficult for you to keep that outsized part of the story in perspective, especially considering the strained relationship between the pair that has persisted to this day?

No. I tried to examine Paul’s story chronologically, so the Simon & Garfunkel years came and went naturally in that process. Unfortunately, Art refused to speak with me, but I spoke to people who knew them both in grade school, others who knew them during the Simon & Garfunkel years, and others who were close to them in the solo years. So, I felt comfortable I got a good insight into the relationship.

Related: What were the top 5 Grammy albums from 1970-74?

Simon’s appearances with Garfunkel, post-split, have been few. Does the book address legit offers for reunion tours and were they ever close to happening?

I kept a constant eye in the book on the relationship between Paul and Art. They are so far apart now, however, that I can’t imagine them ever getting back together. One of the most remarkable discoveries I found during my research was that there was tension between the two from virtually the beginning. When they were teenagers, Paul’s mother said in an unpublished interview, that Art’s father tried to get Paul’s father to sign a contract saying Paul would only write and record with Art. Can you imagine? This was when they were teenagers. Paul’s father refused. He said, in effect, “Paul might want to do something different someday.” He was sure right.

Any great anecdotes post-1981 Central Park concert?

When they were coming off stage that night, neither Paul nor Art had any sense of what a great occasion it was and Paul said Art’s first word to him after the show was, “Disaster.”

Related: Part two of our conversation with Robert Hilburn; Why Paul Simon still matters

Watch Simon & Garfunkel sing “Mrs. Robinson” at the 1981 Central Park concert

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.