Atlantic Records didn’t want to lose Ray Charles in 1959, but ultimately couldn’t compete with the offer he got from ABC-Paramount, granting him complete creative control and higher royalties, a deal that was later sweetened by granting him ownership of all his master recordings should he ever leave the label. Already known as “The Genius,” Charles had considerable success with Atlantic, including the top 10 single “What’d I Say,” but had an expansive view of his capabilities. He was perhaps uniquely qualified to combine rhythm and blues, rock and roll, pop and jazz stylings into a potent hybrid that could have massive national and international appeal.

Atlantic Records didn’t want to lose Ray Charles in 1959, but ultimately couldn’t compete with the offer he got from ABC-Paramount, granting him complete creative control and higher royalties, a deal that was later sweetened by granting him ownership of all his master recordings should he ever leave the label. Already known as “The Genius,” Charles had considerable success with Atlantic, including the top 10 single “What’d I Say,” but had an expansive view of his capabilities. He was perhaps uniquely qualified to combine rhythm and blues, rock and roll, pop and jazz stylings into a potent hybrid that could have massive national and international appeal.

Charles’ last session for Atlantic yielded his version of Hank Snow’s 1950 country hit “I’m Movin’ On,” complete with steel guitar. In the liner notes to his 1959 LP What’d I Say, he mentioned he “used to play in a hillbilly band” [the Florida Playboys] and thought he “could do a good job with the right hillbilly song today.” [Related: The story behind “What’d I Say”]

As he told Ian Dove of New Musical Express during his first visit to England in 1963, “They call my singing ‘emotional’ and ‘full of feeling,’ but that’s how the songs are to me. I try to get the feel of a song and the emotion in it, before I record it. It’s got to move me. And I like to put a little bit of soul into everything. If I don’t feel anything from the song then I forget it. I don’t record it.”

As a consummate singer of songs that tell a story and reveal something about human psychology, the lyrics of “I’m Movin’ On” drew him in. He later told Rolling Stone, “The words to country songs are very earthy like the blues, see, very down. They’re not as dressed up, and the people are very honest and say, ‘Look, I miss you, darlin’, so I went out and I got drunk in this bar.’ That’s the way you say it. In Tin Pan Alley they will say, ‘Oh, I missed you, darling, so I went to this restaurant and I sat down and I had dinner for one.’ That’s cleaned up now, you see? But country songs and the blues is like it is.” He was even more vociferous with author Peter Guralnick: “You take country music, you take Black music, you got the same goddamn thing.”

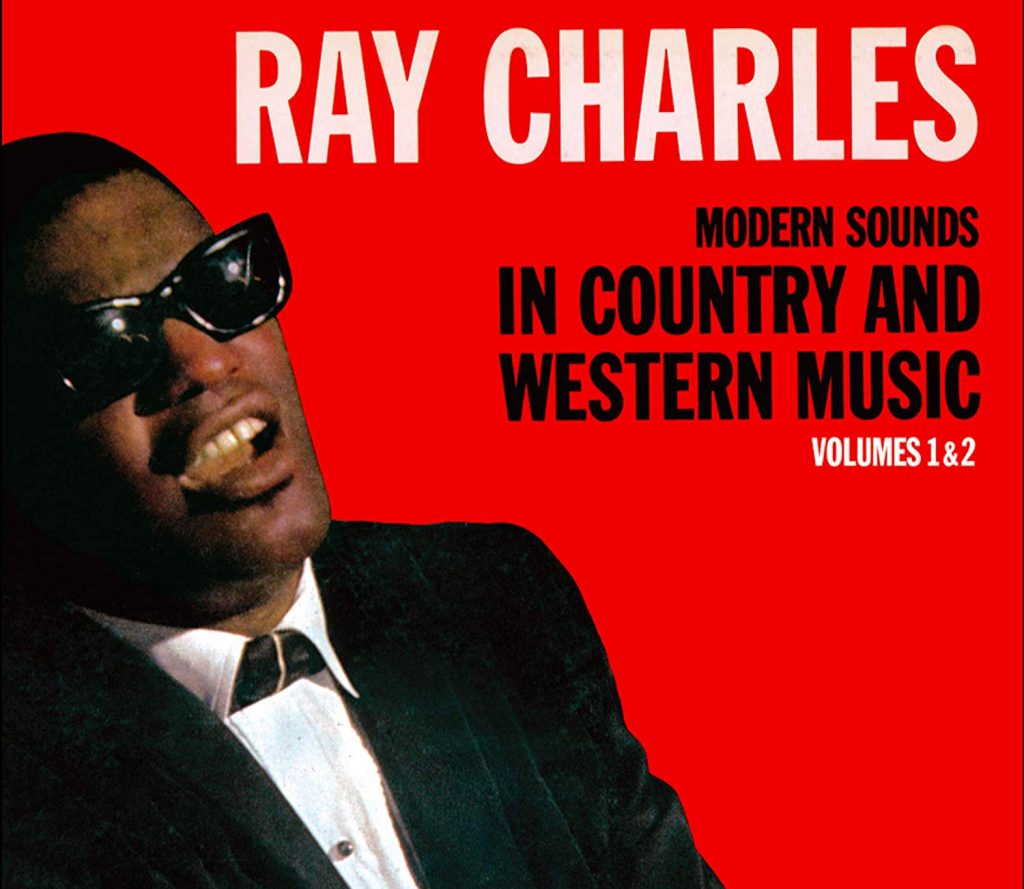

He went all-in with what was then called country and western a few years later, after his spectacular hit “Georgia on My Mind” made him one of music’s biggest stars. Modern Sounds In Country and Western Music was recorded in only a few long sessions in February 1962 at Capitol Studios in New York City and United Western Recorders in Hollywood, and released two months later to immediate commercial success. Charles and Feller produced it, with Bill Putnam and Gene Thompson engineering for a widescreen sound.

The album astonished pop consumers with the quality of the chosen songs, the intensity of Charles’ vocals and the amazing arrangements by Gerald Wilson, Marty Paich and Gil Fuller, which combined genres in new ways, based on detailed piano demos that Charles provided to indicate his orchestral and choral ideas. At first, traditional country music stations didn’t know what to do with it: it was more than unusual for a black artist to present a set of existing country hits in a new setting. But they soon had to play cuts like the first single off the LP, “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” which was a national phenomenon, selling 100,000 copies a week.

To prepare for the sessions, at Charles’ instruction his A&R man Sid Feller gathered 250 possible songs for Charles to consider, mostly from the Acuff-Rose and Peer-Southern publishing catalogs. Growing up in the South, Charles had listened to the Grand Ole Opry and admired the singing of Roy Acuff and Jimmie Rodgers, but any sort of straight imitation was far from his thinking. He explained to Dove, “I don’t think that I am in any way a country singer. That’s why the album is titled Modern Sounds In Country and Western Music. That means a song was still just a piece of music despite the fact it was associated with country artists and usually had a country backing.”

Feller sequenced the LP, and some of his choices have been rightly second-guessed, like starting with “Bye Bye Love,” which had been a huge debut pop hit for the Everly Brothers. Written by the Nashville-based married duo Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, it’s taken at a breakneck pace in a jazz mode. It doesn’t suggest that the Everlys took the song to #1 on the country charts as well as #2 on the pop charts, and doesn’t really give the proper introduction to the LP’s musical concept. It’s Feller’s idea of an attention-grabber, but it’s really one of the album’s weakest cuts.

The ballad “You Don’t Know Me” is next, and the album really begins. Cindy Walker wrote it in 1955; Eddy Arnold and Jerry Vale had rather anemic success with it the following year. Charles turns it into a classic, with Paich’s outstanding work for chorus and strings bringing a ton of romance to a song with seriously downer lyrics. The power of Charles’ vocal is undeniable, but some of his effects are very small: listen to the “oh” he lets out after he sings, “You don’t know the one who dreams of you each night/And longs to kiss your lips/And longs to hold you tight,” or the little rise or melisma he gives to turn “been” and “know” into two syllables and “away” into three. What he does with “I’m afraid and shy” in the bridge section is full of that soul he says he always brings.

There are three songs associated with Hank Williams, and “Half As Much” (written by his unrelated buddy Dock “Curley” Williams) is the first, with a hint of “Sentimental Journey” in the brass and woodwind section. It’s a perfect, relaxed Count Basie-inspired arrangement from Fuller, with tenor saxophonist Don Wilkerson’s funky solo, and doesn’t sound a bit like Hank Williams’ original rhythmically or any other way. Superlatives can be heaped on Charles’ peerless vocal, full of soulful twists. What he does with “You only build me up to tear me down” at the 45-second mark is only topped later by him singing, “I know that I, I could never be this blue” at 2:10, with the quickest falsetto you’ll ever hear.

Hank Williams’ “You Win Again” (a Paich arrangement) and “Hey Good Lookin’” (a rave-up from Gerald Wilson that concludes the LP) contain more gems. Another writer with two credits on the album is Floyd Tillman, with “I Love You So Much It Hurts” (Paich) and “It Makes No Difference Now” (Fuller). Soaring strings begin the first, before Charles enters with the opening title words, stretched out with every ounce of unforced passion. He shows through superb breath and volume control how many different voices he’s got in his throat. His piano playing on this one is also worth noticing.

He starts with piano on “It Makes No Difference Now,” and Fuller again shows his beautiful control of phrasing and harmony in the slow-burning saxophone section. The tempo definitely has some New Orleans in it, and the last minute has some real razzmatazz as Charles practically laughs while he sings against the booming brass.

“Just A Little Lovin’” is a jazz-R&B mover, with David “Fathead” Newman’s blazing sax solo at 1:43. The way Charles handles “I don’t believe you really know how much I love you/If you did you’d come on back and make my dreams come true” might be a nod in the direction of Nat “King” Cole or even Fats Waller. Ted Daffan’s “Born to Lose” and “Worried Mind” end side one and begin side two of the original LP. “Born to lose, I spent my life in vain…That’s a heavy statement,” Charles told his biographer, David Ritz. As good as “Worried Mind” is (more great Charles piano), “Born to Lose” is an icon of recording history. How much pathos can Charles wring out of “heavy” lyrics? How much can you stand?

“Careless Love,” a traditional blues arranged by Charles, is yet another showcase for his absolute command of every syllable of the lyric as he raises his volume, drops up or down in pitch, and tarries behind the beat at will. “Careless Love” leads into “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” which Feller placed in the almost hidden position of next to last on the second side of the LP, deeming it “the weakest” track on the album. Admitting his error, he later said, “Ray never let me forget that.” Paich and Charles have the confidence to allow the chorus to practically shout the lyric “I can’t stop loving you” before Charles interjects “I’ve made up my mind,” and we’re off.

Don Gibson, who wrote the tune, had a country hit with it in 1958, but Feller didn’t consider Charles’ recording pop single material until he found out the actor-singer Tab Hunter was about to issue it with a copycat arrangement from Modern Sounds—with “Born To Lose” on the B-side! He and Charles hurried to edit the brilliant 4:13 album version into a radio-friendly 2:37 so ABC-Paramount could rush out the 45 rpm vinyl. It sold as fast as Elvis Presley’s biggest: according to some accounts nearly a million singles were bought in the first month of release, and on June 23, 1962, the album it came from knocked the West Side Story soundtrack off the #1 slot in Billboard.

Modern Sounds In Country and Western [available in a 2024 edition in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here], released in April 1962, remains a monument to the genius of Ray Charles and his collaborators. Vinyl editions of 1965’s Country & Western Meets Rhythm & Blues [here] and 1966’s Crying Time [here] were also released in 2024. For even more thrills, check out Rhino Records’ four-CD collection The Complete Country & Western Recordings 1959-1986, which includes all of Charles’ country-influenced recordings from his entire career. [His great catalog is available here.]

Watch Charles and the Raelettes perform “I Can’t Stop Loving You” live at Montreux in 1997

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.