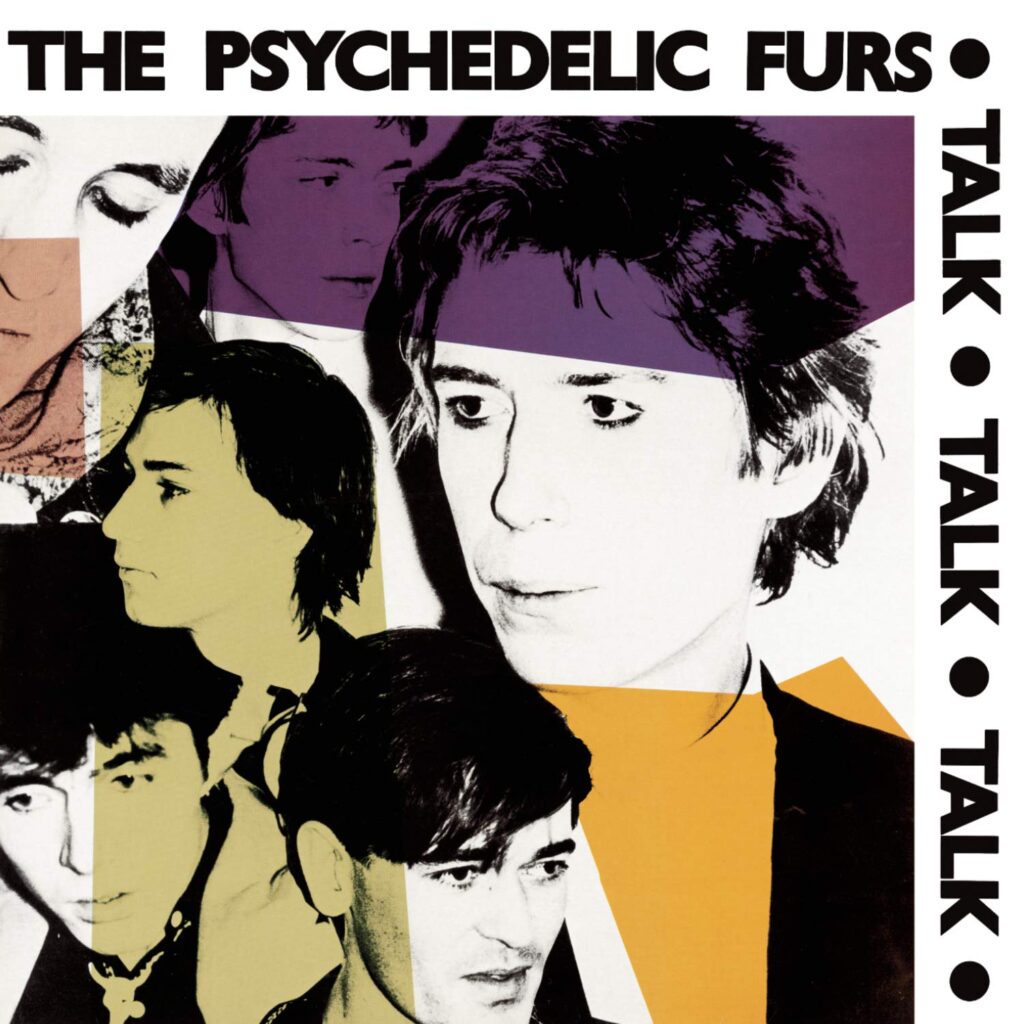

Psychedelic Furs’ ‘Talk Talk Talk’: More Than Just ‘Pretty in Pink’

by Amy McGrath With its raw energy and Richard Butler’s distinctive, darkly romantic vocals, the Psychedelic Furs’ sophomore album, 1981’s Talk Talk Talk, pushed the band beyond its initial post-punk sound, showcasing a more refined yet still edgy rendering. And while the U.S. and U.K. releases shuffled the song order—a draconian mindset still in place back then—it’s a testament that the standout song, “Pretty in Pink,” continues to sonically dazzle the pop music culture nearly 45 years later.

With its raw energy and Richard Butler’s distinctive, darkly romantic vocals, the Psychedelic Furs’ sophomore album, 1981’s Talk Talk Talk, pushed the band beyond its initial post-punk sound, showcasing a more refined yet still edgy rendering. And while the U.S. and U.K. releases shuffled the song order—a draconian mindset still in place back then—it’s a testament that the standout song, “Pretty in Pink,” continues to sonically dazzle the pop music culture nearly 45 years later.

But as legend so often states, this was not an overnight success or a one-hit wonder. In fact, the sextet—vocalist Richard Butler, brother Tim Butler (bass), Roger Morris (lead guitar), John Ashton (rhythm guitar), Duncan Kilburn (saxophone, keyboards) and Vince Ely (drums)—had notched a mark in the U.K. new wave baton with their eponymous debut album in 1980. That release and the single “Sister Europe,” with Butler’s Bowie-like delivery and droning guitars, placed them inside the U.S. Billboard top 200, but not high enough to catch serious fire.

Producer Steve Lillywhite was retained as the band headed into the studio for its follow-up. He had been an enormous influence during the Furs’ first run, producing a large portion of their debut and handing over valuable direction to Butler in terms of stylization and direction. He had also gone on to work on Peter Gabriel’s third album (known as Melt) and U2’s debut album Boy. Based on the more commercial sound (and success) he had achieved, it was no surprise that the Furs’ next album would benefit from the smartened-up polish and technology that Lillywhite offered.

The U.S. album kicks off with the now signature single “Pretty in Pink.” While the previous incarnation of the Furs had them mired in a swampy underground bog, the song launches from the get-go, benefitting from a jangly riff, layered synths and, most pronounced, Butler’s snarly sarcastic observation of a girl with questionable character: “The one who insists he was first in the line/Is the last to remember her name.” Butler revealed in a 2020 interview that “Caroline” was an amalgam of two women he knew and was “about a girl who sleeps around a lot and thinks that she’s popular because of it. It makes her feel empowered somehow, and in fact, the people that she’s sleeping with are laughing about her behind her back and talking about her.”

Later on, the popularity of its theme and sound inspired the John Hughes-produced 1986 film [available here], starring Molly Ringwald, Andrew McCarthy and Jon Cryer. Despite the re-recording of the song for the soundtrack, with its overtly pop-leaning formulation at the time, Butler told this writer in 1991 that “my involvement with the movie was nil.”

Related: British earworms of the early ’80s

For all the perceived slickness associated with the album, “Mr. Jones” is a dip into the churning punk riffs that the band sprang from. Ringing discordant guitars propel the beat as Butler writes another chapter in a sordid book on predatory masculinity and the ugliness surrounding popular culture. The production is a bit of an outlier, as this was a single released in October 1980 and produced by Ian Taylor.

“No Tears,” for all the doom and gloom the band projects, is one of the more uplifting numbers, including Kilburn’s deftly played saxophone solo middle eight break. One of the themes that plays strongly throughout is a sense in oneself, rather than falling into an accepted presumptive diagnosis. Butler’s inflection sometimes belies that message, but the lyrics (“How can you believe in them?/Don’t believe in anything”) is carried along with the spangly twin guitar work of Ashton and Morris, with its homage to both Johnny Marr and Peter Buck.

“Dumb Waiters,” the precursor to the album’s release, had the double pleasure of not only charting the band in the U.K., but also on Billboard’s strangely titled U.S. National Disco Action Top 80 chart at #27. Insofar that the tune would be considered “disco” by 1981 standards, it’s more firmly rooted in the post-punk discord of that time: Butler’s quasi-rap—“Tell her that I’m not in here/Tell her I’m a freak/Tell her that I fall about/Every time I speak”—oscillating instrumentation and a focus in subject that was certainly not unpopular. The era of Thatcherism that had started in 1979 was causing turmoil within the working-class households of young males throughout the U.K.

The tempo comes down and smooths out with “She is Mine.” Gliding along with a Bryan-Ferry style melody, Butler may or may not be curiously referring to distant but related themes that play throughout the album: wanting someone you can’t quite pin down, no matter how hard you try to recall what drew you to them. As he works out numerous stages of a relationship and what avenue he should (or should not) take, the weariness (“They’re making up things that we’ve all heard before/Like romance and engage and divorce/You have to be crazy to stay in this place/You just have to laugh at it all”) to understand that even if you’re a songwriter, you can’t make all the pieces fit no matter how hard you try.

By the time Butler has arrived at “Into You Like a Train,” would he be close to love ballad territory? Of course not. Grabbing your attention like fingernails on a chalkboard, the tune is neither a metaphor for sex or a paean to a loved one. Rather, like many who heard it then and still do in the 21st century, Butler is able to make the rollercoaster feelings of love indistinguishable with dance and movement. The actual wording may be a little hard to decipher vis a vis “If you believe that anyone like me within a song is outside it all/Then you are all so wrong,” yet the band’s churning atmosphere confirms over and over that when you’re pogoing around on the floor, every emotion is (as George Harrison said) within you and without you.

“It Goes On” is bit shouty this far into the album. There’s a talk-box quality to the Ashton and Morris combination, as Tim Butler provides a slightly higher mixed melodic bassline. Kilburn and Ely provide the standout contributions to this track with pronounced drum and sax solos. Granted, it’s hard to dismiss the energy the group is bringing to this tune, yet the trademark “hard” ending that comes (as it does through nearly every song), leaves it feeling more of a rush-to-the-finish than it should be.

The tribal backbeat of “So Run Down” is indicative of the U.K. music scene then, as it mimics Adam and the Ants (minus the satirical humor) as it plunges into line with an Echo and the Bunnymen gothic swirl. Butler’s patented Drano-like vocals were far removed from Ian McCulloch’s high-register plaintive pleas, however one can draw the conclusion that many bands had been listening to each other quite closely, given the striking similarities in sound, presentation and exposure that Top of the Pops gave all of them during that time period.

Not that anyone would confuse rockabilly grunge with the Furs, the curious-sounding “I Wanna Sleep With You” features one of the more direct and clear vocals from Butler. As the rest of the band bashes around in a hopscotch, mad march-stepping time signature, Butler spits and sputters couplets like “And I won’t hold your hand/I won’t give you flowers” and “These go-go girls are happening/They’re just like accidents.” It all sounds quite menacing and misogynistic…until you dig deep and realize it’s not him directing the song’s title. It’s her.

After all the straight-to-it songs, the album’s longest track (at 6:25), “All of This and Nothing” feels like the fitting conclusion—and for the U.S., it was. Opening with a subdued motif, the band keeps this the cleanest narrative of the entire collection, strung together as a litany of life happenstances that circles back through a relationship of “what ifs.” Descriptive in its most minimalist terms, Butler is somehow poetic in his attempt at wrapping up an album’s worth of music in one song. With a few “fake” breaks, and an extended instrumental coda, it nearly succeeds.

Released with differing tracklist configurations in the U.K. and U.S. on May 15, 1981, Talk Talk Talk climbed as high as #89 in Billboard. The band received its greatest visual exposure after the launch of Music Television (MTV) in August with the hyper-surrealistic music video for “Pretty in Pink.” [Furs recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

The band is on tour this summer. Tickets are available here.

Watch the Psychedelic Furs perform “Pretty in Pink” live from the House of Blues

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.