When Patti Smith described her 1975 debut album Horses as “three-chord rock merged with the power of the word,” she was connecting herself to two artistic streams. First, there was the relatively simple “garage” sound of groups like Count Five, ? and the Mysterians, the Seeds, Chocolate Watch Band, etc., which she—and her longtime guitarist Lenny Kaye—felt epitomized the primal power of American rock.

When Patti Smith described her 1975 debut album Horses as “three-chord rock merged with the power of the word,” she was connecting herself to two artistic streams. First, there was the relatively simple “garage” sound of groups like Count Five, ? and the Mysterians, the Seeds, Chocolate Watch Band, etc., which she—and her longtime guitarist Lenny Kaye—felt epitomized the primal power of American rock.

Second, she was asserting that the poetry of masters such as William Blake, Walt Whitman and Arthur Rimbaud, and their 20th century acolytes Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Charles Olson, could be spiritually integrated into music that would aspire to literary heights. As Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Jim Morrison, Robert Hunter and other Smith-approved poet-composers had already proven, lyrics could be literature.

In the ’60s, sometimes existing poetry was incorporated verbatim, as when the Doors used Blake’s lines “Some are born to sweet delight/Some are born to the endless night” on their debut album, when Judy Collins sang an arrangement of W.B. Yeats’ “Golden Apples of the Sun,” the Fugs’ blasted Ginsberg’s poems, or when Peter and Gordon set e.e. cummings’ “As Freedom Is a Breakfast Food” to music on their Hot Cold & Custard LP in 1968. Also in ’68, Joan Baez cut an entire album of sung poems by Donne, Rexroth, Lorca, Rimbaud, etc,. called Baptism. In the folk and rock scenes, the history of poetry was ripe for rediscovery.

Patti Smith had made the transition from standard poetry readings to performances with Kaye’s guitar accompaniment, eventually working with a full band, performing at the Mercer Arts Center , Reno Sweeney, Max’s Kansas City, CBGB and other New York City venues and dive bars. She would use tunes like “Paint It, Black” or “Land of 1,000 Dances” as launching pads for improvised verse, and eventually issued a 45 rpm single, “Hey Joe (version),” backed with “Piss Factory,” on the Mer label, partly bankrolled by art collector Sam Wagstaff and her lover, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

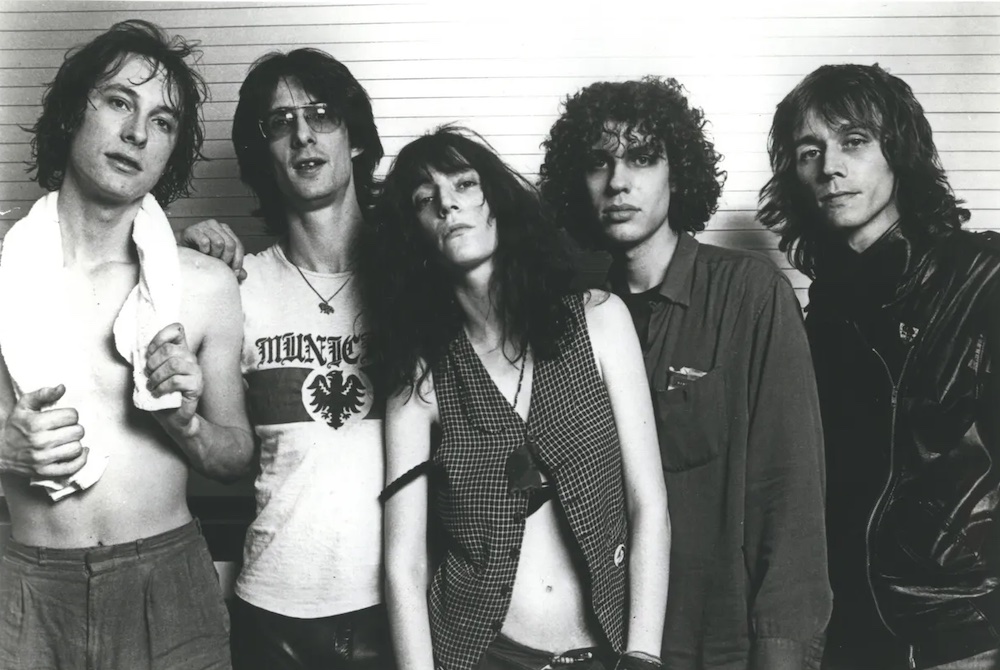

The Patti Smith Group (l. to r.): Jay Dee Daugherty, Lenny Kaye, Patti Smith, Richard Sohl, Ivan Kral (late ’70s publicity photo)

Eventually signed to Clive Davis’ new Arista label, Smith designed Horses as her own living art manifesto, one of the most important opening shots in what became punk rock. “The record is a document of a group becoming a group,” Smith told Sounds’ Robin Katz. Choosing the celebrated Velvet Underground member and solo recording artist John Cale as producer, Smith and band (pianist Richard Sohl, drummer Jay Dee Daugherty, bassist Ivan Kral and Kaye) recorded during August and September 1975 at Electric Lady, the studio founded by Jimi Hendrix, another of Smith’s heroes.

Cale told journalist Lucy O’Brien in 1996 he’d found Smith “someone with an incredibly volatile mouth who could handle any situation,” and described their working relationship as “confrontational and a lot like an immutable force meeting an immovable object.” For her part Smith told Katz, “The thing with Cale is that we fought constantly. It was fantastic. The thing is, he’s intense and I’m intense and I’m relentless…I think things should happen fast. I don’t believe in overdub and all that mixing. I believe in doing it and just doing it right. Spontaneity.”

Smith had published three books of poetry before the band was fully formed; as she told Rolling Stone, with the musicians behind her “Of course I wanted to work in the rock ’n’ roll tradition. I didn’t know any other tradition existed.” She often gave the musicians co-writing credits, since their exploratory work on stage spurred new elements of her own creativity. For Horses, the idea was to capture the power of those unpredictable live performances. “But,” Smith continued, referring to Cale, “I hired the wrong guy, All I was really looking for was a technical person. Instead, I got a total maniac artist. I went to pick out an expensive watercolor painting and instead I got a mirror.”

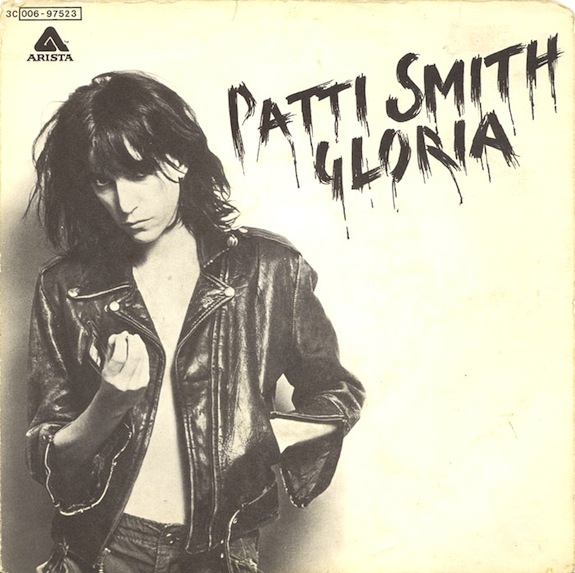

Over a beautiful but ominous two-chord piano/bass duet, Smith enters “Gloria (In Excelsis Deo)” with her voice in the center of the crystal-clear mix, intoning, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine,” recast from her poem “Oath.” The melody quickly reveals itself as a derivation of Van Morrison’s “Gloria,” but with Smith’s cascading lyrical observations and a Mick Jagger strut: “People say beware but I don’t care/The words are just rules and regulations to me…I look out the window, see a sweet young thing/Humping on the parking meter/Oh, she looks so good/Oh, she looks so fine…”

Over a beautiful but ominous two-chord piano/bass duet, Smith enters “Gloria (In Excelsis Deo)” with her voice in the center of the crystal-clear mix, intoning, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine,” recast from her poem “Oath.” The melody quickly reveals itself as a derivation of Van Morrison’s “Gloria,” but with Smith’s cascading lyrical observations and a Mick Jagger strut: “People say beware but I don’t care/The words are just rules and regulations to me…I look out the window, see a sweet young thing/Humping on the parking meter/Oh, she looks so good/Oh, she looks so fine…”

Smith tries on a variety of voices, and toys with gender expectations, as the band fully enters and speeds up, until the whole thing threatens to go off the rails with the “G-L-O-R-I-A” chorus and subsequent banging freakbeat. There’s a false ending after a slow-down that suggests the singer might be exhausted, but it turns out to be a James Brown-style feint, Much credit to engineers Bernie Kirsh and Frank D’Augusta for capturing so much sonic complexity with clarity.

Related: The story of “Gloria”

“Redondo Beach” is an immediate change, to loose reggae, but the lyrics, based on an argument Smith had with her sister Linda before going into stark fiction, remain intense: “I went looking for you, are you gone gone/Down by the ocean it was so dismal/Women all standing with shock on their faces…Everyone was singing girl is washed up/On Redondo Beach and everyone is so sad.” Smith uses a pinched vocal tone with occasional yips at the end of lines. The band has a tentative feel, as if they’re not quite sure what to do. Perhaps this performance hints at what Smith meant when she told journalist Dave Marsh of her admiration for one of Phil Spector’s most potent vocalists, quipping “My goal is to be as good as Darlene Love.”

As semi-autobiography, “Redondo Beach” has something in common with “Kimberly,” a rhythmic, almost poppy song with lyrics drawn from Smith’s memory of holding her younger sister during a lightning storm, and with “Free Money,” in which Smith portrays her difficult upbringing in New Jersey by channeling her mother’s voice as she fantasizes about a financial windfall: “Every night before I go to sleep/Find a ticket win a lottery/Scoop the pearls up from the sea/Cash them in and buy you all the things you need/Every night before I rest my head/See those dollar bills go swirling round my bed.” Sohl handles the poignant piano, the kind of thing that might grace an Elton John recording, until once again the band speeds up and, with tremendous drumming from Daugherty, it all reaches a wilder denouement, with several voices intoning “when we dream it…free money.”

The totally improvised, nine-minute “Birdland” was inspired by A Book of Dreams, Peter Reich’s memoir of his controversial psychoanalyst father. In the book, Peter imagines that at his father’s funeral, he boards a UFO with his dad at the controls. With a snaking, distorted guitar throwing shapes in the background (it sounds like both Kral and Kaye are playing electric 6-strings here), Smith throws out a trance-like combination of recitation, shouts, chants and doo-wop singing. She’s said that her feeling of not fitting into her family, or even our world, led to the notion she was born on another planet. Hence the progression in her feverish vision in “Birdland”: “he was not human…you are not human…I am not human.” Pointing to the track’s free-jazz roots, she ends by referencing the New York club where Charlie Parker used to hold forth, declaring “We like Birdland.”

“Break It Up” is perhaps the LP’s most complex arrangement, with Television’s Tom Verlaine (born Thomas Joseph Miller, stage name from the French poet) adding crucial guitar lines that mimic and play off Smith’s aggressive vocal, which by the end of the track is starting to crack. According to Smith, the lyrics refer to her visit to Jim Morrison’s grave in Paris, and a dream she had in which a winged Lizard King struggled to fly: “Snow started falling/I could hear the angel calling/We rolled on the ground, he stretched out his wings/The boy flew away and he started to sing/He sang ‘break it up’/Oh, I don’t understand.”

The three-part “Land” is over nine minutes, and is the most radical recording on the album. Smith once claimed in The New York Times she’d lost a notebook containing twenty verses of “Land,” that she masturbated and got high while writing sections of it, and that the lead characters of Johnny and “the horse” pivoted around a variety of current obsessions, including the protagonist of William Burroughs’ novel The Wild Boys, Hendrix and Rimbaud. In her 2012 memoir Just Kids, she refers to Mapplethorpe and Burroughs, taking in a show at CBGB, as “Johnny and the horse.”

“Land” contains dreamy, elliptical narrative elements (“The boy was in the hallway drinking a glass of tea/From the other end of the hallway a rhythm was generating”), snippets from Chris Kenner’s “Land of 1,000 Dances” and “I Like It Like That,” amended to include the exhortation “you’ve got to lose control!,” and long sections where two Smiths compete with each other to dominate the foreground while the band pounds out a variety of thicknesses and colors behind them. “I have a lot to learn about records and mixing and things like that,” Smith told the Times, “but nobody can tell me about the magic. The magic is completely under control.”

Horses concludes with “Elegie,” recorded at Smith’s insistence on the fifth anniversary of Hendrix’s death on Sept. 18, 1970. It’s meant to pay tribute to rock’s casualties, including Janis Joplin, Brian Jones, Morrison and Hendrix. As Smith told the Los Angeles Times’ Robert Hilburn upon the album’s November 10, 1975, release, “Psychologically, somewhere in our hearts, we were all screwed up because those people died. We all had to pull ourselves together. To me, that’s why our record’s called Horses. We had to pull the reins on ourselves to recharge ourselves. We’ve gotten ourselves back together. It’s time to let the horses loose again. We’re ready to start moving again.”

Smith’s boyfriend Allen Lanier (of Blue Öyster Cult) adds ethereal guitar to “Elegie,” and Sohl once more provides the stately piano. Smith finds multiple voices to express her sadness, sobbing, keening and pleading her way through (for her) fairly straightforward lyrics: “I just don’t know what to do tonight/My head is aching as I drink and breathe/Memory falls like cream in my bones/Moving on my own/There must be something I can dream tonight.”

Horses peaked at #47 on the Billboard album chart, but had a much larger impact than that commercial measurement might suggest. It was embraced as a musical milestone by critics, and anyone who caught Smith as she toured the U.S. in late ’75 and 1976 was blown away. With many of the shows broadcast on the hipper FM radio stations, numerous concerts became legendary (Paul’s Mall in Boston, the Roxy in Los Angeles, the Cellar Door in D.C., the Boarding House in San Francisco). She was incapable of doing the same show twice, and when she hit Europe in May ’76, the enthusiasm there rebounded back to her home country.

In her long career, Smith has only had one hit single, “Because the Night,” written with Bruce Springsteen, but her influence has been enormous; her incendiary live shows are still rituals to savor. In 2009, Horses was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation into the National Recording Registry as a “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” work. It’s all three.

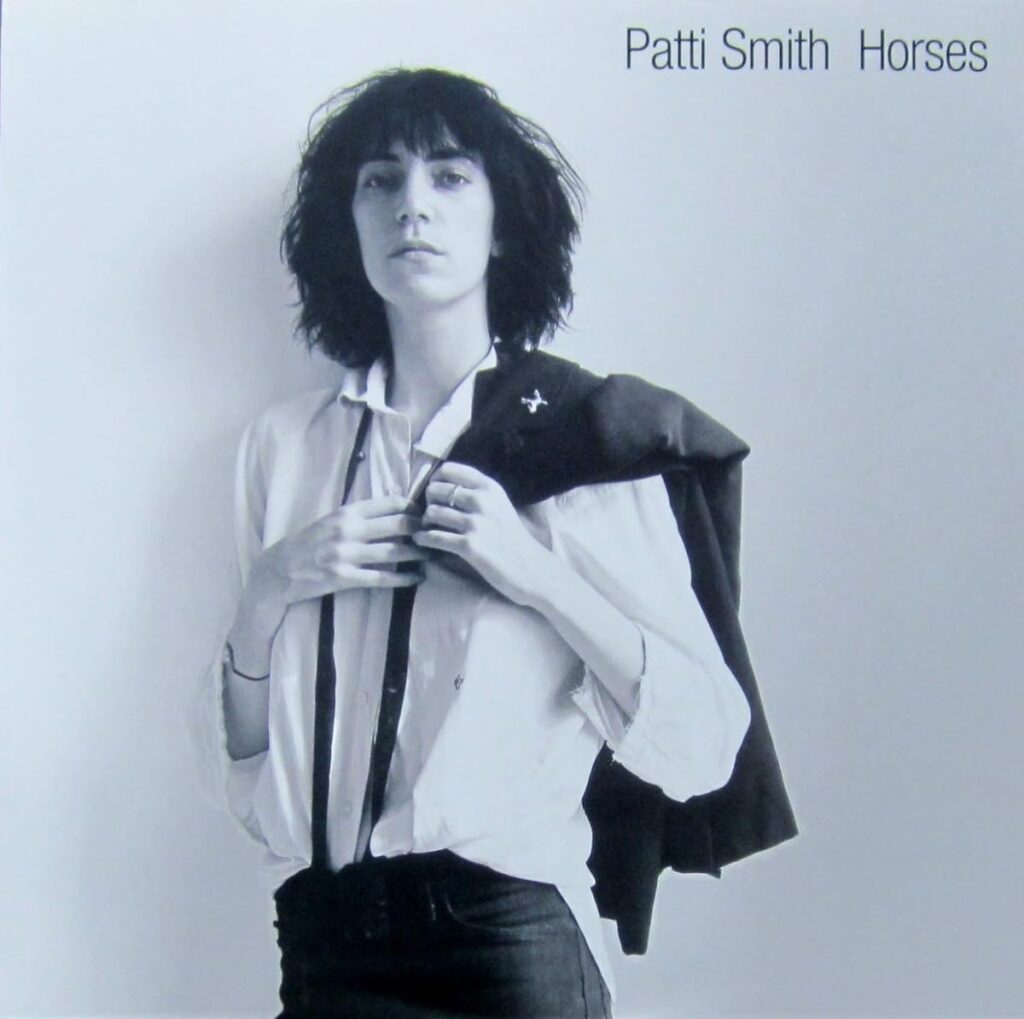

Even the album cover, shot by Mapplethorpe, became iconic: Smith’s androgynous look and insouciant pose make their own statement. Look closely and you can see the horse pin, a gift from Lanier, on her lapel. In the liner notes to the 2005 expanded reissue of the album, Smith explained, “I overslept the day we shot the cover of Horses. I dressed hastily in the clothes I wore, like a uniform, on the stage and in the street. Robert worked swiftly, wordlessly. He had a nervous, confident manner. He had no assistant. There was a triangle of shadow he wanted…He asked me to remove my jacket because he liked the white of my shirt. I tossed the jacket over my shoulder Sinatra-style, hopefully capturing some of his casual defiance…I believe we captured some of the anthemic artlessness of our age. Of our generation.”

Watch Smith perform the title track on England’s Old Grey Whistle Test

Horses received a 50th anniversary edition in 2025. The album, and other Smith recordings, are available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. She published a memoir, Bread of Angels, on Nov. 4, 2025. The title is available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.