In October 1979, Neil Young was interviewed in Los Angeles by the KMET-FM DJ Mary Turner, and didn’t hold back regarding the release of his most recent projects, which were based on the innovative and strange tour with his band Crazy Horse the previous year. “I like it if people enjoy what I’m doing, but if they don’t, I also like it,” he told her. “I sometimes really like aggravating people with what I do. I think it’s good for them.”

In October 1979, Neil Young was interviewed in Los Angeles by the KMET-FM DJ Mary Turner, and didn’t hold back regarding the release of his most recent projects, which were based on the innovative and strange tour with his band Crazy Horse the previous year. “I like it if people enjoy what I’m doing, but if they don’t, I also like it,” he told her. “I sometimes really like aggravating people with what I do. I think it’s good for them.”

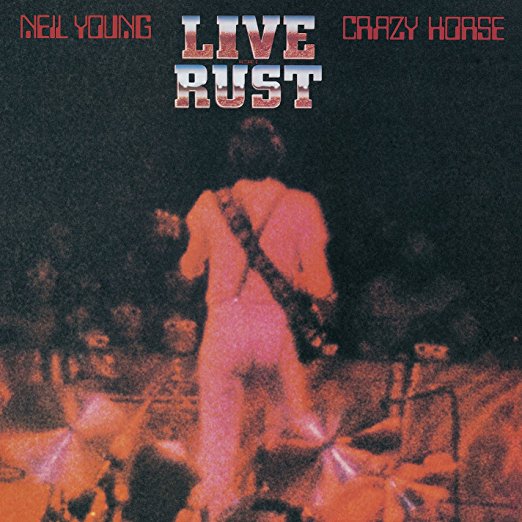

The Rust Never Sleeps LP, comprising studio tracks and judiciously overdubbed live recordings, had been issued in July, and a film of the October 22, 1978, show at San Francisco’s Cow Palace had been released under the same title. A double-LP soundtrack drawn from five different concerts, Live Rust put forward the raw experience of hearing a tight band pushed by their leader to conjure the wildness of punk rock and the sheer power of volume and noise. Young’s photographer Joel Bernstein recalled the run of 24 concerts from September 16 to October 24 as “incredibly loud, unbelievably loud.”

Young was using a new custom stomp box that allowed him to jump between or combine effects for his vintage Les Paul. He wore a Jimi Hendrix button on his guitar strap during the tour, and played Hendrix’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” from Woodstock as part of the arena shows. During the making of his movie Human Highway in 1978—it wasn’t completed for release until 1982—Young had spent considerable time with Devo, and collaborated with their leader Mark Mothersbaugh on an early version of what became two songs that bookended the heart of the concerts, “My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)” and “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black).” Young described Human Highway as a film “made up on the spot by punks, potheads and former alcoholics.”

Watch Neil Young and Devo’s uncut “Hey Hey, My My”

As Young explained in his memoir Waging Heavy Peace, the ’78 tour “was going to be from the standpoint of a young boy dreaming. All the amps were huge and there was going to be a giant microphone. It was going to be like Tom Thumb in reverse. The roadies were all like Jawas from Star Wars! A cone-headed wizard was the lighting director, and some scientists in lab coats were the sound mixers. It was all like a hospital experiment, with the scientists appearing in lab coats during the performance, taking notes on clipboards and the Jawa-cloaked roadies with their illuminated eyes raising and lowering amp cases over the top of the amps from the ceiling by pulling on ropes with pulleys…It was billed as Rust Never Sleeps: A Concert Fantasy.” “Rust-O-Vision” glasses were distributed, supposedly so audiences could watch Young and Crazy Horse decay before their eyes.

In 1975, Crazy Horse had been reconstituted after the death of Danny Whitten by bringing in Frank “Poncho” Sampedro on guitar and backing vocals. Ralph Molina was the drummer/singer and Billy Talbot played bass and sang too. “It was great,” Talbot said of the group chemistry. “We were all soaring.”

Live Rust begins with five solo acoustic songs, all recorded at the Cow Palace save “After the Gold Rush,” with Young on piano, from Boston Garden. That classic, along with “Sugar Mountain,” “I Am a Child” and “Comes a Time,” are played solidly and solicit mostly respectful silence, with occasional whoops of encouragement from the rowdier patrons. The reaction to “My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)” is something like awe, as the audience hears “It’s better to burn out than to fade away” for the first time, and reacts to the other audacious lyrics—including the call-out to Johnny Rotten—with palpable enthusiasm.

“I wrote that song right after the death of Elvis Presley,” Young says in Waging Heavy Peace. “I wrote it referring to the rock and roll star, meaning that if you go while you are burning hottest, then that is how you are remembered, at the peak of your powers forever. That is rock and roll.” Young’s friend Jeff Blackburn is credited as co-writer for some crucial lyrical help. Mothersbaugh doesn’t get his name on it, even though he suggested the addition of “rust never sleeps,” a slogan for the industrial paint-makers Rust-Oleum that he remembered from his days in Akron, Ohio.

Crazy Horse kicks in full-tilt with the Cow Palace “When You Dance I Can Really Love,” a tune originally worked up in Topanga Canyon in L.A. for the After the Gold Rush album, and the momentum continues with a version of “The Loner” from Chicago that crushes the original studio version.

After a duo of contrasting cool-off tunes, “The Needle and the Damage Done” and “Lotta Love,” recorded in St. Paul, Minnesota, Crazy Horse goes pretty far into the punk zone with “Sedan Delivery,” another slammer from the San Francisco show. It had been around in Young’s vault for two years in more polite versions before this much more aggressive take debuted.

The opening verse lays out the somewhat surreal scenery: “Last night, I was cool at the pool hall/Held the table for eleven games/Nothing was easier than the first seven/I beat a woman with varicose veins.” The drug-dealing narrator tells a dislocated story; near the end Young goes into full rant mode. Tempo changes abound. (“Sedan Delivery” was one of several songs Young offered to Lynyrd Skynyrd for their Street Survivors sessions, but they passed on all of them.)

Side three of the original Live Rust vinyl set is overwhelming. It begins with “Powderfinger,” also new to the Crazy Horse setlist. Narrated by a dead man, it unfolds with the power of myth: “Just think of me as one you never figured/Would fade away so young/With so much left undone/Remember me to my love, I know I’ll miss her.” The Young/Poncho guitar duel in the center section is epic Crazy Horse. Following quickly, a nearly eight-minute version of “Cortez the Killer,” recorded in St. Paul and originally in studio form on 1975’s Zuma, is greeted with screams from the audience.

In recent years, Crazy Horse has been known to stretch “Cortez the Killer” to 20 minutes, and it’s so full of drama it sustains that length. Once again, the rhythm section is superb, the backing vocals float, and Young brings a sui generis passion to his singing and guitar shredding. The melody soars with “And the women all were beautiful/And the men stood straight and strong/They offered life in sacrifice/So that others could go on.” Young’s high, keening voice is magnificent. Unfortunately, he goes into a Jamaican accent near the end of the performance, apparently for comic effect.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s debut, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere

A blistering “Cinnamon Girl” follows, with its killer riff and enigmatic words: “A dreamer of pictures, I run in the night/You see us together chasing the moonlight.” (What exactly makes a girl cinnamon anyway?) As to the guitar solo, Young once opined, “People say that it is a solo with only one note, but in my head, each one of those notes is different. The more you get into it, the more you can hear the differences.” For the finale, Young leads the band into the kind of feedback/noise territory they’ll explore even more in the ensuing decades, including the noise collage album Arc released to accompany the Weld live set in 1991.

“Like a Hurricane” begins with a fusillade of noise before the overdriven guitar riff from Young begins. His new guitar effects pedal gets a workout on this masterful take recorded in Chicago. The song, which quickly became one of Young’s signature tunes, made its debut on American Stars ’N Bars; it was one of the first tracks recorded in 1975 when Sampedro joined the band. An edited version was released as a single in 1977 but didn’t chart.

After thanking the crew and audience, Young leaves the stage, returning for an encore, the grungy “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black).” The distortion on both Young and Sampedro’s guitars is full on. “You pay for this, but they give you that/Once you’re gone, you can’t come back.” When Kurt Cobain quoted from the song in his suicide note in 1994, Young was distraught: “When he died and left that note, it struck a deep chord inside of me. It f**ked with me…I don’t think he was interpreting the song in a negative way. It’s a song about artistic survival, and I think he had a problem with the fact that he thought he was selling out, and he didn’t know how to stop it.” Young had reached out to Cobain before, but to little effect.

Live Rust concludes with an outstanding, eardrum-blasting, seven-minute St. Paul dash through “Tonight’s the Night.” It pays homage to Young’s fallen comrades Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry in a way that says the future is going to be full of exploration and energy, and that nobody’s resting on their laurels. Honor the past, mourn those you’ve lost, but the future for Crazy Horse is going to be LOUD.

Although few saw Rust Never Sleeps in theaters, Live Rust, released on Nov. 14, 1979, made it to #15 on Billboard’s Top 200 album chart, and the Rust Never Sleeps LP made it to #8. In the still-growing Neil Young catalog, they are two of the highlights. Neil Young and Crazy Horse continues with Nils Lofgren rejoining after Sampedro’s retirement; their latest release is 2022’s World Record, and they played live in September 2023 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Roxy nightclub in Los Angeles.

Live Rust, and other Young recordings are available to order in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and the U.K. here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI was at the St. Paul show. It was overwhelming. After the final song and cheering no one spoke until we were outside, like leaving church.

I saw them at the Miami Arena circa 1982 and was aware of the volume as it had been written about in one of the publications. So I bought a ticket as far back as possible, in the very top row. Didn’t matter! My ears hurt for a week after that show! Yes it was loud, but the group emphasized a low frequency distortion that added to the toughness of the sound. What memories!

Neil Young at his BEST! I love both of these albums. The concert film is great too! It’s time to release the whole tour on digital music. During this time when disco ruled, Neil was pumping out his best music.

I always thought cinnamon refers to hair color, sort of a dirty blond with darker and lighter highlights.

Great post, Neil is such a forever talent.