Ray Thomas, the flutist, singer and composer of the Moody Blues, died in his sleep at his home in Surrey, England, on January 4, 2018, following a battle with prostate cancer. He was 76.

Thomas was among six members of the progressive rock band who were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s Class of 2018.

Best Classic Bands interviewed Thomas and fellow former member Mike Pinder in August 2017, in what appears to be his final interview. On his website, Thomas noted that he was diagnosed with inoperable prostate cancer in September 2013.

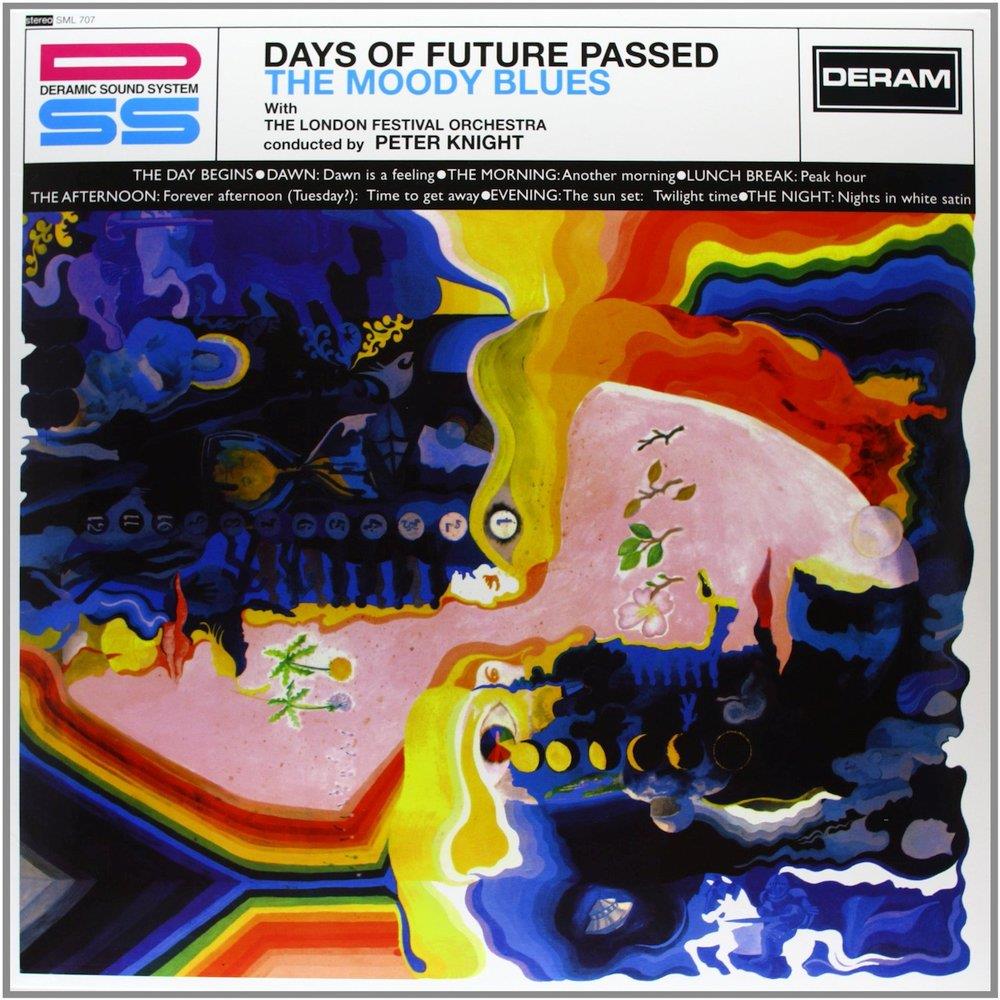

The English musician was born December 29, 1941, in Stourport-on-Severn, England. He composed several of the songs on the group’s landmark 1967 album, Days of Future Passed, including “The Morning: Another Morning” and “Twilight Time.”

Thomas’ other compositions for the group include “Dear Diary” from 1969’s On the Threshold of a Dream and “For My Lady” from 1972’s Seventh Sojourn.

Watch Thomas sing “For My Lady” with the Moody Blues and a full orchestra

That August 2017 interview appears below…

When most people think of The Moody Blues, the group’s classic 1967 album Days of Future Passed immediately comes to mind. But the Birmingham, England-based group started out years earlier as an R&B outfit. Various members had played together in other bands; one calling itself the Krew Cats—and featuring Ray Thomas and Mike Pinder—played an extended engagement in Hamburg, Germany, the city in which the Beatles had cut their musical teeth just a few years earlier. “We played the Top Ten Club in 1963,” says Thomas.

“Hamburg was an education,” says Pinder. “But we weren’t getting paid, and at the end Ray and I were broke. We didn’t have a pot to piss in!” They ended up at the British Embassy, where they asked for enough money to get themselves home. Pinder laughs about it now. “It was just part of our musical journey.”

The first lineup calling itself the Moody Blues got together in spring 1964, and included Thomas (vocals, tambourine, harmonica), Pinder (keyboard and vocals), drummer Graeme Edge, guitarist/singer Denny Laine and Clint Warwick on bass and vocals. With four singers, the group was able to build a varied repertoire that featured strong vocal harmonies.

The early Moody Blues scored a number of hits in England, and one worldwide hit in “Go Now.” But the band splintered by 1966. “Clint Warwick was the only married guy in the group,” says Pinder, “and his wife wanted him to have a steady gig. Denny Laine thought he would do better making his way on his own.” (After a subsequent string of unsuccessful groups, Laine teamed up with Paul McCartney in 1971 to form Wings.)

Watch the original lineup perform “Go Now”

“Our management had made off with any earnings from ‘Go Now,’” says Pinder, “so we didn’t have managers or money.” Looking for a follow-up to their big hit, they even considered a song offered to the group by McCartney, but in the end decided the tune wasn’t right for the Moodys. Instead, Mary Hopkin recorded the song, “Those Were the Days,” and scored a worldwide smash hit.

“When Denny left, we got John Lodge back in on bass,” Thomas says. Lodge—a band mate of Thomas’ even before the Krew Cats—had been the first choice for the original Moody Blues lineup, but he was busy then with college studies. But the band still needed a guitarist.

The Animals’ Eric Burdon had been on the hunt for a new guitarist/singer himself. “He’d advertised in the local musical press and found somebody,” Thomas says. “I was having a drink with him in a club, and he said, ‘I’ve got a load of replies in my office; if you want to go through them, you’re more than welcome.” The Moody Blues did so, and checked out two or three musicians. They quickly settled on Justin Hayward.

Related: Our coverage of the Moodys’ Rock Hall 2018 induction

“John and Justin were the perfect additions to the band,” says Pinder. Hayward even brought a new song along, “Fly Me High.” Released in 1967 as a single, it didn’t chart, but stylewise it bridges the gap between “old” Moody Blues and the new musical approach they would soon adopt.

That new style was built on an idea from Pinder. He had worked for the company that built the unique Mellotron, a tape-based forerunner of modern sampling playback keyboards. A notoriously fickle instrument, it had only rarely been used in a rock context, the most prominent early example being the “flute” sound heard on the Beatles’ 1967 single “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

The Beatles and the Moody Blues were close friends; in fact, Pinder says that both he and Thomas played on some Beatles recordings. “Ray and I sang harmonies and played mouth organ on ‘The Fool on the Hill’ and ‘I am the Walrus,’” he recalls. “I respected and admired the amazing talent of the Beatles, and I knew that if any musician should have a Mellotron, they should.” Eventually each of the four Beatles purchased one.

The versatile instrument’s temperamental nature was no challenge to Pinder. “I knew how they were built. I knew how to put the Mellotron together and how to take it apart,” he says.” He replaced some of the less-useful sounds with more practical tapes containing orchestral strings and the like.

Watch the original “Nights in White Satin” video

“I had been playing flute,” recalls Thomas, “so it was an ideal marriage for the flute with the strings. We decided to really do it like a classical-rock fusion, I suppose you’d call it.” The new and distinctive band sound came first, followed soon by the songs that took on that sonic character.

Around that time, executives from the group’s British label, Decca, approached the Moody Blues with an idea for a kind of hybrid album. Conductor Peter Knight would record Antonín Dvořák’s 1863 Symphony No. 9, the New World Symphony. “And we were supposed to play rock ’n’ roll classics,” says Thomas. “You know, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis and whatever.”

But the Moody Blues had ideas of their own. “We initially wanted to do a stage show with the Mellotron,” recalls Thomas. “And Peter Knight went along with it, God bless him. So did Tony Clarke.” Clarke was a staff producer at Decca, and Pinder says his support was critical. “We considered Tony to be the sixth Moody,” he says.

The band and Clarke developed an even more ambitious plan for the album. “I had always wanted to create something that was conceptual,” Pinder says. “I loved the works of Mantovani. I wanted to have our albums on people’s shelves … albums that people would want to collect, and play in their entirety.”

Work began on what would become Days of Future Passed, with Knight composing for the London Festival Orchestra while the band worked separately with Clarke. The Moody Blues wrote and recorded eight songs that, taken together, formed a concept: a day in the life of an everyman. At least two of the songs, “Tuesday Afternoon” and “Nights in White Satin,” were destined to become classics. “We were all writing songs,” Pinder says. He considers Days of Future Passed the successful result of a winning combination: “the use of the Mellotron, the input of Tony Clarke, the support of Decca, the ambience of the studio and the combined creativity of the band members.”

Ray Thomas, in an undated photo via Esoteric Records

Work in Decca’s four-track studio progressed at a rapid pace. “We were recording one and two songs a day,” Thomas says, “which we were used to doing. Because you got no time at all in the studio in those days.” At the end of each day’s recording, the band would send a tape copy of its work to Knight. “He’d got his own little writing room in his house; it was in his garden shed, actually,” Thomas says with a chuckle.

Knight’s orchestrations provided the link between the pop songs; taken together the work was one of the earliest exemplars of what’s now known as progressive rock. “We were not there when the orchestra parts were done,” Pinder says. “But we had a wonderful group listening session after they added their contributions. We loved what they had done.”

Thomas has nothing but fond memories of the 1967 sessions, and shares a favorite moment. “When we did ‘Nights in White Satin,’ the four of us got ’round a mic and sang in harmony,” he recalls. “And then Tony [Clarke] said, ‘Let’s do another take.’ He was doubling it up!” The group finished the take and then went into the studio control room. “When I heard the playback, it was like a mini choir,” Thomas says. “There were a few tears shed.”

Sessions for Days of Future Passed were completed in 10 to 12 days, Thomas recalls. And those recording dates also yielded an ode to LSD guru Timothy Leary, “Legend of a Mind,” a song the band would set aside for its next album, 1968’s In Search of the Lost Chord.

When the album was complete—it was mixed by Clarke along with engineer Derek Varnals—Clarke summoned the band back to the studio for a playback. “We all went down to the studio and turned all the lights off,” Thomas says. “We sat there and put it through a couple of big speakers. And we freaked out!

“But when Decca heard it,” Thomas says, “they panicked: ‘Who’s going to buy this? It’s neither one thing or the other: it’s not rock ’n’ roll, and it’s not classical as such.’” Happily, Walt McGuire, head of London Records, the Decca affiliate in New York, championed the project. Thomas recalls McGuire announcing in a meeting, “Well, if you’re not going to release it, I will.” The Decca executives reluctantly agreed.

On its November 1967 release, Days of Future Passed did reasonably well on the British album chart, reaching #27. The single of “Nights in White Satin” only made it to #19 there, with no success in the U.S.

The band wasn’t too worried, though. “We were just thrilled that we’d got it released,” Thomas says. “We knew what was happening live, and we were getting great reviews.”

The 1968 followup single, “Tuesday Afternoon,” fared better in the U.S., reaching #24, and there were hit singles like “Question” (1970) and “The Story In Your Eyes” (1971), but the band finally hit paydirt in 1972. When re-released in America that year, Days of Future Passed soared to the #3 spot on the Billboard chart, and the “Nights in White Satin” single, on its second go-round, made it to #2 on Billboard’s Hot 100 single chart.

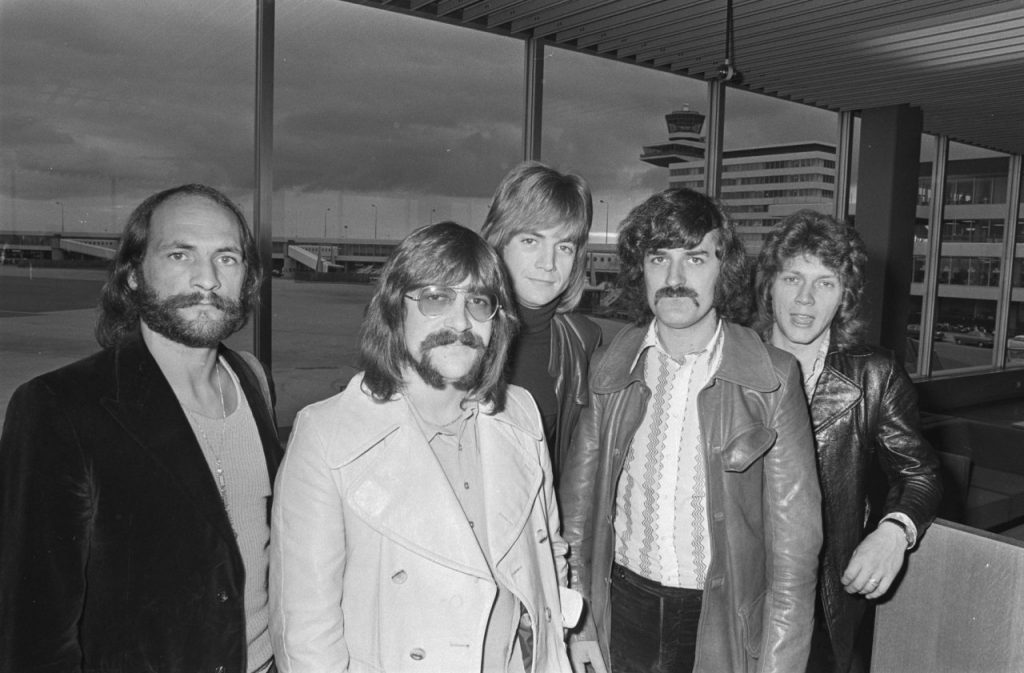

The Moody Blues in 1970 (l. to r.): Mike Pinder, Graeme Edge, Justin Hayward, Ray Thomas, John Lodge (Photo from the band’s Wikipedia page)

The Moody Blues would go on to make seven more albums with the lineup of Thomas, Pinder, Edge, Lodge and Hayward. Weary of touring, Pinder left after 1978’s Octave. Thomas continued with the band through its MTV-era resurgence and beyond, retiring from the group in 2002.

Related: Our 2018 concert review of Justin Hayward

With the exception of a Christmas album (2003’s December), the Moody Blues wouldn’t release any new material after Thomas’ departure, but the group continues as a popular draw on the concert circuit. And despite a long-held self-imposed ban on performing Pinder’s compositions without him (“We wouldn’t have somebody else sing a Mike Pinder song,” Edge told this writer in 2010. “It wouldn’t be right; there’s a phoniness to that”), the current lineup of the Moody Blues commemorated the 50th anniversary of Days of Future Passed with start-to-finish live performances of the album.

Related: Edge died in 2021

And Pinder is okay with that. While he admits that it has always been “a bit weird” to hear his music recreated onstage without him, he says, “I am certainly proud of our legacy. And after all, Days of Future Passed was conceptual, and meant to be played in its entirety.” He recently received an email from Lodge, in which the bassist wrote, “I am singing ‘The Sunset.’ It’s a great song, and I hope I am giving it the love and attention that you would have given it. I hope you like it; it’s important to me that you do.”

“We made the music as a loving team,” Pinder says. “And John’s attitude reflects that feeling.” He reflects on the legacy of Days of Future Passed. “We recorded it at a time when music and technology collided,” he says. “We were young, eager and ready to be part of the creative London musical landscape. We had the great opportunity during those sessions to reflect the changing times and the inner searchings of young people like ourselves in our songs. And I do feel that Days of Future Passed does stand the test of time.”

Pinder died in 2024.

Watch a live version of “Tuesday Afternoon” from 1970

The Moody Blues’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. When Lodge and Hayward tour, tickets are available here.

8 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationTy for the story,pics,and video.To me,they were genius,along with Tony Clarke.Days of Future Past is my all time favorite album,period…

Ditto!

Much emphasis on the mellotron’s role in the Moodies’ music, but Thomas’ flute played a large role in much of it, too. Give it all a listen, and you will hear.

You should know your favourite album is actually called Days of Future PASSED.

The Moody Blues were one of the most important musical and spiritual influence in my teenage years and beyond. I play their songs for my little granddaughters and they love their music also. Love to all of the moodys.

I was lucky enough to make two animations for founder Ray Thomas: “Floating” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQ_Glm2zl0E

and the animated ad for the Moodies 50th anniversary box set:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBp7Mdyz5pw

Thanks to Ray wherever you are and to Mike Pender for featuring my Moody Bluegrass t00n on his site mikepender.com!

Ray’s solo album, Hope, Wishes & Dreams is a beauty. The final song, “The Last Dream” is quite devastating.