By the late 1960s, the Motown label’s “Sound of Young America” was in need of a change. Founder Berry Gordy had always emphasized mainstream entertainment values when deciding what to release, and the famed Quality Control Department at Motown not only insisted on high-caliber technical sound, but examined lyrics for anything that might be controversial. As the AM and FM airwaves filled with songs that reflected the mixed-up state of the world (“White Rabbit,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Taxman”), Motown only allowed a few overt “protest songs” on the label, such as Stevie Wonder’s polite take on Dylan’s “Blowin’ In the Wind” in 1966.

By the late 1960s, the Motown label’s “Sound of Young America” was in need of a change. Founder Berry Gordy had always emphasized mainstream entertainment values when deciding what to release, and the famed Quality Control Department at Motown not only insisted on high-caliber technical sound, but examined lyrics for anything that might be controversial. As the AM and FM airwaves filled with songs that reflected the mixed-up state of the world (“White Rabbit,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Taxman”), Motown only allowed a few overt “protest songs” on the label, such as Stevie Wonder’s polite take on Dylan’s “Blowin’ In the Wind” in 1966.

When hit songwriters Holland-Dozier-Holland decamped in 1967 over a pay dispute, other writing teams filled the gap, and Gordy reluctantly allowed Motown productions to psychedelicize and topical subjects to enter the mix. By 1970, the label had enjoyed massive hits with the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion,” the Supremes’ “Love Child” and Edwin Starr’s “War.” It turned out reality could sell.

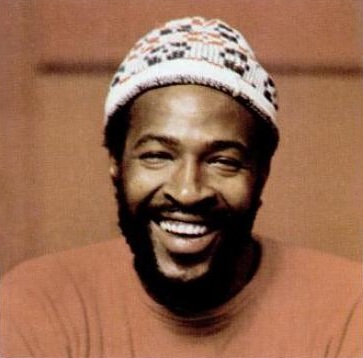

Marvin Gaye had made his name at Motown with smooth love songs and dance numbers like “Pride and Joy,” “Ain’t That Peculiar,” “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)” and “I’ll Be Doggone.” In 1969 he was in a deep depression, frustrated by his lack of artistic development, despondent over the break-up of his marriage to Gordy’s elder sister Anne, shocked by his singing partner Tammi Terrell’s sudden brain cancer diagnosis, and struggling with his fondness for cocaine and alcohol. Swamped by the expectations of others, especially Berry Gordy, he told an interviewer, “I had a mind of my own and wasn’t using it.”

In addition, he’d been profoundly moved by the letters his brother Freddie had written while serving in the Vietnam War. Gaye began to think there must be some way to incorporate his feelings about civil rights, politics, ecology and current events into his art. He later told Rolling Stone, “I began to re-evaluate my whole concept of what I wanted my music to say.”

In addition, he’d been profoundly moved by the letters his brother Freddie had written while serving in the Vietnam War. Gaye began to think there must be some way to incorporate his feelings about civil rights, politics, ecology and current events into his art. He later told Rolling Stone, “I began to re-evaluate my whole concept of what I wanted my music to say.”

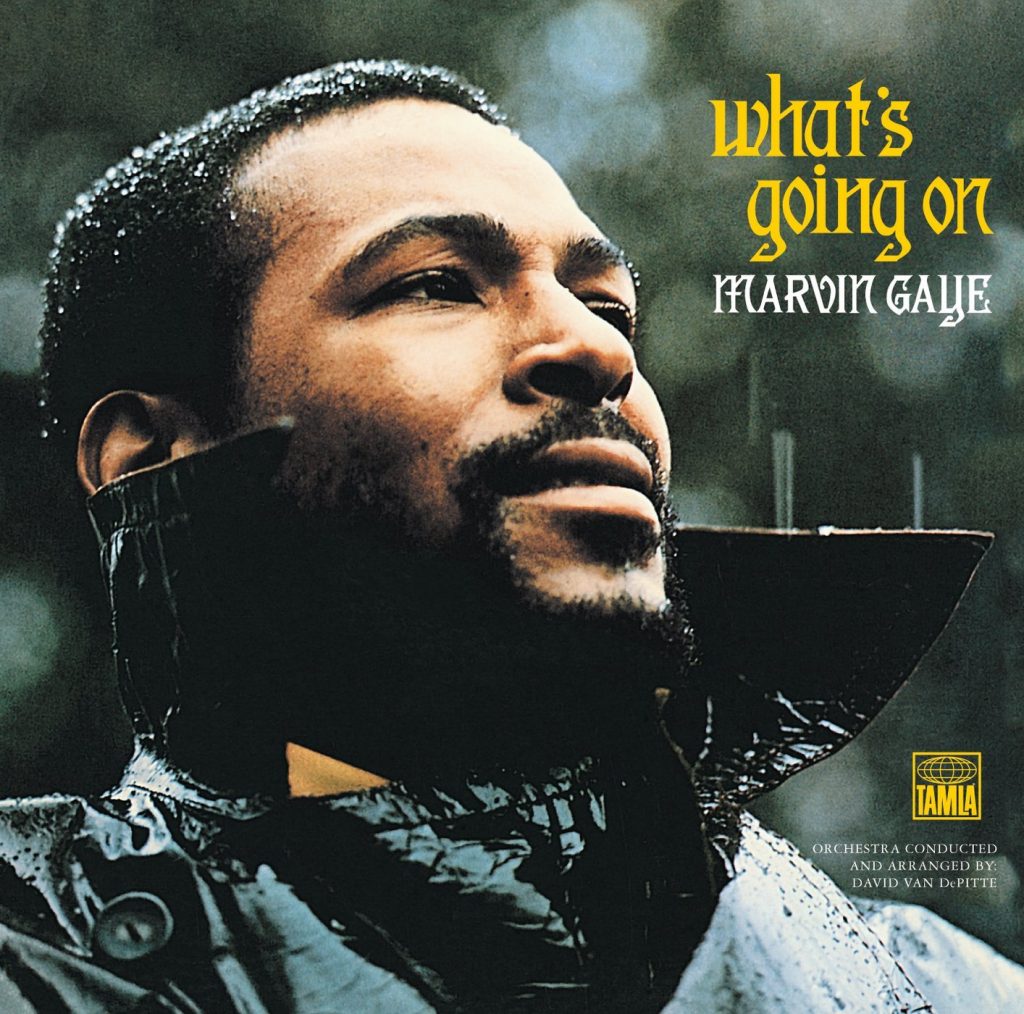

When the Four Tops’ Renaldo “Obie” Benson showed Gaye a song he’d written after witnessing police brutality at Berkeley’s “People’s Park” in May 1969, Gaye was enthusiastic, and began to tinker with it. Staff writer Al Cleveland (who’d co-written “Baby, Baby Don’t Cry” and “I Second That Emotion” for Smokey Robinson and the Miracles) contributed as well. The song became “What’s Going On,” which Gaye arranged to record in Motown’s “Hitsville U.S.A.” studio in Detroit, taking the reins of production himself instead of relying on Motown staffers as usual. Basic tracks were recorded June 1, 1970, with lead and background voices overdubbed in July and strings added in September.

“What’s Going On” was constructed with many of the players dubbed “The Funk Brothers,” plus some crucial supplements, like Eli Fontaine’s alto saxophone and drummer Chet Forest. Gaye’s vocal is both hopeful and melancholy, full of impact but not flashy: “Mother, mother/There’s too many of you crying/Brother, brother, brother/There’s far too many of you dying.” Recording engineers Steve Smith and Kenneth Sands accidentally created a multi-track vocal effect that Gaye loved, and insisted be retained. Marijuana and scotch were consumed during sessions that veered from laid-back to intensely focused. One day, bassist James Jamerson arrived drunk, and recorded his parts lying on the floor. David Van DePitte’s string arrangement, based on hummed lines from Gaye, added a sophisticated, jazzy air.

When presented with the finished recording, Gordy was still skeptical (one report has him calling Gaye “ridiculous—that’s taking things too far”) and Motown refused to release it. Gaye went on strike. Motown execs Barney Ales and and Harry Balk conspired to press up a 45 rpm single behind Gordy’s back, complete with a radio-unfriendly false fade that writer Harry Weinger says was Gaye’s “little f**k-you to Motown.” When the single was released on January 20, 1971, on Motown’s Tamla subsidiary, R&B and pop radio jumped on it, and it sold 100,000 copies the first week. It went to #1 on Billboard’s Hot Soul chart and was only prevented from hitting #1 on its Hot 100 by Three Dog Night’s “Joy To the World.”

Gordy was forced to admit he’d been wrong—in fact, he now unreasonably insisted Gaye immediately supply the rest of an album for rush-release. Between March 17 and 30, Gaye and company, working in Detroit, with additional overdubs in Los Angeles on May 5, recorded the LP that Rolling Stone anointed in 2020 as the greatest album of all time. It yielded two more pop chart smashes on top of the title cut, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology),” which reached #4, and “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” which made it to #9. All three topped the Billboard Soul chart, a unique achievement at the time: no artist had managed three #1’s from the same LP.

Watch Gaye perform the title track live in 1972

Related: The biggest radio hits of 1971

The full story of the recording process is covered expertly in Ben Edmonds’ What’s Going On? And the Last Days of The Motown Sound, David Ritz’s Divided Soul and other books [available here]. This is an album that remains fresh, and only grows in stature over the years. Each song blends into the next, creating a true song cycle, a story told from the point of view of a returning military veteran. Using a literary device that had roots in his own family, Gaye reveals his state of mind and emotions in a deeply personal way.

“What’s Going On” starts the LP with a party atmosphere and the greeting “What’s happening brother?” that were not present on the single version. The groove is light, the chorus vocals and strings beautifully laid in, and Gaye’s vocal—often rising into his pure falsetto—is sublime. “What’s Happening Brother” follows, continuing the groove and narrative thread, running into “Flyin’ High (In the Friendly Sky),” which gets its title from a popular airline ad of the period and introduces the state of mind of a heroin user: “Flying high without ever leavin’ the ground…I got to the place where the good feelin’ awaits me/Self-destruction in my hand/Oh Lord, so stupid minded/And I go crazy when I can’t find it.” The song is credited to Gaye, Anna Gordy Gaye and Elgie Stover. Gaye’s voice, mostly in high register, shows the longtime influence of Curtis Mayfield.

“Save the Children” is another Gaye/Cleveland/Benson collaboration, and contains spoken lines alternating with heartfelt, spontaneous-sounding gospel melodies: “When I look at the world it fills me with sorrow/Little children today are really gonna suffer tomorrow.” The arrangement is full of color, with bongos, conga, vibraphone, saxophone, strings and wordless chorus doing their part. This is the kind of stellar work that gained David Van DePitte his unusual, prominent credit on the front cover of the original LP, for conducting and arranging the orchestra.

The short “God is Love” returns strongly to the sonic landscape of “What’s Going On,” and connects love for others to love of Jesus (“He loves us whether or not we know it…He’ll forgive all our sins/And all He asks of us, is we give each other love”). Gaye is unafraid to wear his spirituality on his sleeve, and it’s especially audacious that the track merges with “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology),” which suggests humans haven’t been good stewards of the God-given planet.

Related: Marvin Gaye killed by his father, 1984

The first Earth Day, a celebration meant to increase public awareness of environmental degradation, had occurred on April 22, 1970, and Gaye was clearly “woke” on the subject at a time when many weren’t. It’s his only solo writing credit on the disc. “Radiation underground and in the sky/Animals and birds who live nearby are dying/Oh, mercy mercy me/Things ain’t what they used to be.” On tenor sax, Detroit legend William “Wild Bill” Moore enters at 3:40 and owns the track’s coda, while an angel chorus, strings and killer rhythm section do their thing. It ends the first side of a perfect album.

“Right On,” the album’s longest cut at 7:32, begins side two with a Latin groove from percussionists Jack Ashford and Jack Brokensha (the scratch of a güiro most prominent), flutes by Dayna Hartwick and William Perich, and a brilliantly loose, jazzy vocal during which Gaye shows off all his most engaging, intimate effects. “Wholy Holy” slows things down. Gaye’s voice winds around saxophone, celeste and strings for an atmospheric, devotional song that twins with “God is Love” on the first side. Gaye sings, “He left us a book to believe in/In it we’ve got an awful lot to learn/Oh, wholy holy, oh Lord/We can conquer hate forever.”

The concluding song is credited to Gaye and James Nyx, a writer for Motown’s Jobete publishing arm who also worked as a janitor and elevator operator. “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” begins with dramatic piano and percussion, then restrained guitar and bass enter (Bob Babbit replacing Jamerson as he does on “Mercy Mercy Me”). Gaye starts scat singing (which Gordy apparently hated, feeling it was old-fashioned), before settling into a seductive multi-tracked performance in which he calls to and echoes himself. In the middle he scats again, while some very tasty saxophone and percussion licks flow, after which he whoops with delight, and screams, in the midst of the very serious lyrical content (“Trigger happy policing/Panic is spreading/God knows where we’re heading”). The fade, with Gaye’s voice, congas and sax in glorious juxtaposition, ends the LP like a benediction.

When What’s Going On was released on May 21, 1971, it reached #6 on the U.S. album chart and topped the R&B chart.

Marvin Gaye’s life tragically ended in 1984, after many more hits, personal struggles and a difficult split from Motown. The 2001 expanded reissue of What’s Going On, with alternate mixes and a tremendous live concert recorded May 1, 1972, at the Kennedy Center, is a must for any music collection. Unfortunately, America is still struggling with many of the issues permeating this masterpiece. What’s Going On remains a monument to Marvin Gaye’s big heart and soul, and a prophecy for our time.

Listen to “Inner City Blues” recorded live at the Kennedy Center in 1972

Gaye’s recordings, including this one, are available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.