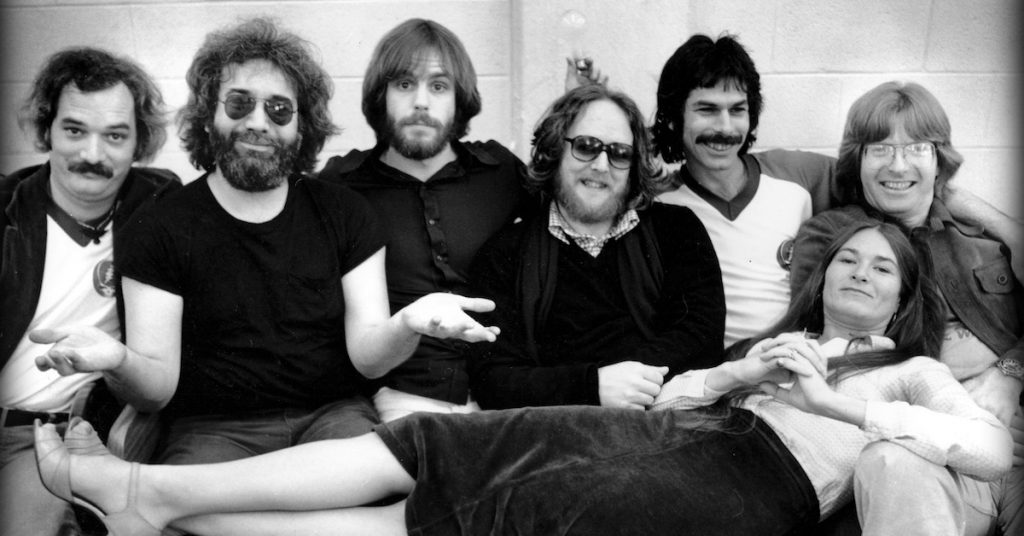

The Grateful Dead backstage in 1977 (l. to r.): Bill Kreutzmann, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Keith Godchaux, Mickey Hart, Phil Lesh, Donna Jean Godchaux (Photo © Peter Simon; used with permission)

A couple is exiting an advance screening of the four-hour Grateful Dead 2017 documentary Long Strange Trip. “So, what did you think?” the male half asks his companion. “I never really liked them,” she responds with a slight sigh, “but at least now I get it.”

That, one would imagine, would please the creators of this poignant, enlightening film just fine. Long Strange Trip, directed by Amir Bar-Lev, with Martin Scorsese among the executive producers, is a sprawling collection of transcendent highs and the occasional free-falling low, much like a Dead concert. And like one of those often extraordinary, sometimes maddening bacchanals, it’s daring and fearless, unpredictable, often given over to tangents, embracing of chaos, golden to insiders and perplexing to outsiders.

The documentary, which is available on DVD and Blu-ray (with more than two hours of additional material, including a full set rom 1970 and backstage footage), enjoys—again much like its subject—tossing out mischievous bolts of surprise, perilously navigating hair-raising turns and diving head-first into the unknown. It’s not free of bloat, yet even at this length—roughly akin to that of a typical Dead show (it even has an intermission)—it leaves its audience both spent and wanting more.

The documentary, which is available on DVD and Blu-ray (with more than two hours of additional material, including a full set rom 1970 and backstage footage), enjoys—again much like its subject—tossing out mischievous bolts of surprise, perilously navigating hair-raising turns and diving head-first into the unknown. It’s not free of bloat, yet even at this length—roughly akin to that of a typical Dead show (it even has an intermission)—it leaves its audience both spent and wanting more.

If Long Strange Trip plays like no other music doc before it, that’s how it should be: The Grateful Dead was like no other band. Among the only major rock acts whose world was built upon live performances rather than recordings—hence their eventual decision to allow fans to tape and trade their concerts—they were also, certainly, the only rock band to breed a literal caravan of followers. The Dead Heads, a phenomenon that began taking shape less than a decade into their 30-year run, eventually numbered in the millions, the most dedicated among them structuring their lives around the reluctant countercultural deities creating the music, traveling from venue to venue.

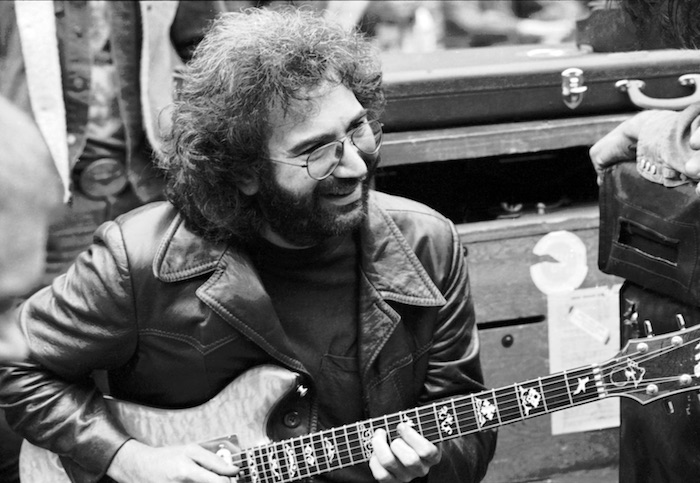

Jerry Garcia backstage before a Grateful Dead concert in Golden Gate Park 09/28/1975 (Photo © Roberto Rabanne, used with permission)

That intense devotion, the film makes quite clear, became both a blessing and, ultimately, the Dead’s undoing, a problem of gargantuan proportions. By the time it was all over, with the death of Jerry Garcia in 1995, there were more fans congregated outside of the shows than witnessing the band inside the venues. Many were destructive, there for the party more than for the music. In retrospect, it was inevitable: Long Strange Trip plots that trajectory masterfully.

From the start, Bar-Lev makes ample use of vintage Frankenstein footage to illustrate that vital point. There’s a twofold purpose for that device (which, despite its cleverness, verges on getting old fairly quickly): First is Garcia’s admiration for the character. The 1948 film Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein was a life-shaper for him as a kid. Scared out of his wits, the 6-year-old barely looked up at the screen, yet he became a horror movie fan for life and, although he could not yet articulate it, a relentlessly curious adult unafraid to explore worlds beyond the known, to take risks and sort out the inevitable calamities later.

The other, more obvious reason, is to drive home the truth that the individuals at the center of this maelstrom were constitutionally unable—and stubbornly unwilling—to govern the monster of their creation. Garcia, a fierce antiauthoritarian, was interested in little more than playing his guitar—always. He’s rarely seen without it, and the arc of the film reiterates that his inherent inability to deal with and utter lack of concern for the mundane issues that affect highly popular rock bands, such as finances and crowd control, were part of what led to his, and the band’s, demise.

Related: When the Dead and the Beach Boys jammed

l. to r.: Jerry Garcia, Donna Godchaux and Bob Weir–and the Dead Heads–in 1978 (Photo © Ed Perlstein; used with permission)

As they grew in stature, the Grateful Dead became a sizable business enterprise whose survival depended on the musical entity at the core remaining productive. Families’ lives counted on that machine continuing to churn, and the Dead’s decision to take a year off in the mid-’70s to reconsider their purpose only led to more and more of everything—especially excess. Even when the band did have down time, which most musicians might use to chill and catch their breath, Garcia packed his guitar case and headed out to the clubs and theaters with his solo bands.

As the virtual army of Dead Heads swells, it doesn’t take a working knowledge of the band’s history to sense that tragedy is inescapable. By the end, morbidly obese and disheveled, Garcia’s body ravaged by drugs, tobacco and lousy diet, the halo that had surrounded him was gone. The Grateful Dead may have defined freedom but they were enslaved by it. Cue Dr. Frankenstein.

That’s all for later though. The first half of Long Strange Trip is, by necessity, primarily a celebration of all the good stuff that the Dead and the hippies and rock music and the ’60s came to represent. Their detractors may remain so even after the four-hour immersion, but like the woman leaving the theater who now “gets it,” most should, at the very least, come away with a fuller understanding of what went on there and why.

Bar-Lev lays out the chronology, the footage and the interview clips meticulously, covering the major historical touch points, allowing for ample commentary and elucidation at each step, but he’s not interested in turning out an academic study nor a hagiography. If there’s one sentiment that repeatedly rears its head, it’s that these people who called themselves the Grateful Dead—and we hear the oft-told story of their random naming once again too—were in it for the fun. They say so, early and often: fun was their motivation; if it ain’t fun, why bother? The film, even while attempting to explain the unexplainable—makes sure to leave plenty of room for for yuks and giggles. Being in the Dead, being in their audience, was a blast. Only when that fun became threatened did the dark cloud move in.

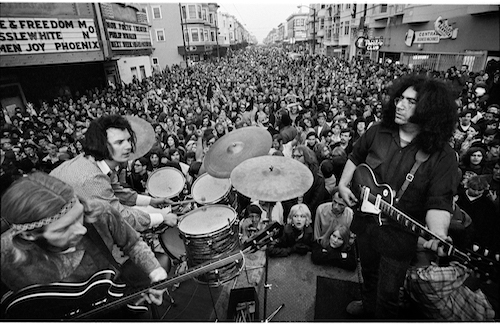

The Grateful Dead performing on San Francisco’s Haight Street 3/3/1968 (l. to r.): Phil Lesh, Bill Kreutzmann, Jerry Garcia (Photo: © Jim Marshall Photography LLC, used with permission)

You get the sense from what’s said and shown that the Dead and their audience, at least in the early years, made every attempt to remain equals, that the star trip was anathema to them. Yet there’s also no denying that being an actual member of the Grateful Dead—not being a roadie or a soundman or an “old lady” or a manager (Sam Cutler, one of them, is hilarious) or a beleaguered record company exec charged with herding them onto vinyl (rhythm guitarist/singer Bob Weir once wanted to record the sound of air)—brought with it a unique perspective and a set of attendant responsibilities.

Related: Ron “Pigpen” McKernan plays final show with the Dead, 1972

The history, an understandable handful of gaps aside, is accounted for, via anecdotes, interviews and a generous helping of archival clips. There’s the oddly colliding musical backgrounds of the original members (blues, bluegrass, folk, classical, R&B, jazz, early rock ’n’ roll, avant-garde, etc.); the influence of the Beat writers; the succession of epiphanies that came with the fortuitous meeting of this young, oddball rock band and writer Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters. Not to be denied is the massive impact of psychedelic drugs on their development (“The single most significant experience of my life.”—Garcia) and the experimentalism that LSD brought to the music.

Although often considered the quintessential ’60s band, Long Strange Trip reaffirms that the Dead didn’t really find their stylistic groove until the early ’70s, by which time their role as designated ambassadors of San Francisco free-spiritedness was well established. The music diversified—and, fortunately, there is plenty of it to be heard throughout the film—and, in many ways, became tamed: the lysergic extremes of the acid days became tempered, giving way to their first commercial breakthroughs: the acoustic-based 1970 albums Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty that redefined them as post-psychedelic Americana cowboys.

Watch the Dead perform “Ramble on Rose” in Philadelphia, 1989

The band’s 1972 European tour and, later, a 1978 jaunt to Egypt, are given proper examinations, although seminal ’60s events like the Monterey Pop Festival and even Woodstock merit nary a mention (come to think of it, neither does 1973’s Watkins Glen show with The Band and the Allman Brothers Band, attracting what was at that point the largest concert audience in history). What is covered in often terrifying detail is the late ’80s explosion in popularity that resulted in a top 10 album (In the Dark) and single (“Touch of Grey”) but also caused an unstoppable swelling in the size of the audience, many of whom were now too young to have a sense of what it was like at the beginning.

The band’s approach to what bassist Phil Lesh calls “collective improvisation”—the foundation of the Dead’s live music—is given the respect it deserves even if, as one of their two drummers, Bill Kreutzmann, says, “I didn’t know what song it was sometimes.” Bar-Lev never forgets that, above all else, the music had a life of its own.

Fans who have already seen countless hours of Grateful Dead footage will, nonetheless, still find much here to delight them. An intimate look at an early rehearsal of the acoustic “Candyman” gives insight into the band’s creative process.

The level of scrutiny fans apply to dissecting the nuances of specific performances is illustrated with an appropriate mix of reverence and hilarity by no less than Sen. Al Franken, who waxes on knowledgeably about his favorite version of the tune “Althea.” In addition to most of the surviving band members and collaborators (don’t ever ask Garcia’s songwriting partner Robert Hunter to define his lyrics), ex-employees and associates, several super-Dead Heads are also given substantial screen time to discuss why, say, a particular version of “Morning Dew” is the one to live for. Much of it might be inside baseball to the less enamored, but the hardcore will hang on every word.

Among its many strengths, Long Strange Trip serves to remind just how long and strange it really was, overuse of that phrase be damned. The group’s innovation with concert sound technology—their mid-’70s “Wall of Sound” speaker setup was truly revolutionary—is worthy of the dissection it’s given (“The voice of God,” Lesh calls it), all in the service of delivering to the audience the most pristine reproduction possible of what’s happening onstage.

But also among its strengths is the film’s refusal to scapegoat or sugarcoat. The spiral downward from drugs of enlightenment to drugs of damage—cocaine and, particularly, Garcia’s heroin problem and the devastating effect it had on his ability to maintain the ingeniousness of his playing—is afforded the same openness as the Dead’s positives. When we hear Garcia moan backstage that he doesn’t feel like performing an encore, he just wants everyone to go home, we know that a tide has turned. Later on, toward the end, his addiction having returned after temporarily subsiding, we’re shocked to listen to the revelations of an ex-wife, summarily dismissed by the guitarist for a request that any non-addict would undoubtedly find reasonable.

Watch the Dead perform “Morning Dew” in San Francisco in 1974

That Jerry Garcia is at the crux of the film is undeniable, but Bar-Lev takes pains to ensure that it’s clear he was, by his own design, never any kind of leader. Neither, for that matter, was anyone. Toward the end, stalked by a city-sized mob of what Cutler doesn’t hesitate to call “lunatics,” the Dead was a rudderless ship hurtling toward its inevitable crash. “Jerry didn’t bargain to be the mayor of a cultural town,” says former Dead publicist Dennis McNally, but with no one else willing to assume that office, an entity as large as theirs had no place else to go but smack into a dead end.

Dead Heads in the tapers’ section at an outdoor venue late-1980s (Photo by Michael Conway; used with permission)

The final hour of the film becomes more fraught with horror upon horror—Frankenstein unbound is not very friendly. We see some fans literally bowing down to their own mythical Garcia; what was once about the music and the shared ecstasy has been hacked by something else more sinister. “They should have buried the Grateful Dead before it buried Garcia,” Cutler suggests, yet even as those involved saw what was happening around them, there was no way to prevent it from playing out, no one to say the word enough.

If all of that sounds more than a bit depressing, be reassured that Long Strange Trip is, overall, a joyous experience, a magnificent work of art that rivals any previous music documentary (including Scorsese’s own The Last Waltz). It doesn’t attempt to be comprehensive (some legit band members are never even mentioned; nor is promoter Bill Graham, a key figure in bringing them to the public), but it doesn’t need to be. It’s so much more than just another tale of what McNally calls “the most American of all bands” and another associate less charitably calls “the most dysfunctional family that’s ever been created on this planet.”

Long Strange Trip does, of course, chronicle the life of a band, but more than that it’s about what happened when an increasingly large community of followers took up the ethos of a laissez faire group of musicians and songwriters—founded upon the guiding principal of what one interviewee deems “leaving yourself open to magic”—and ran with it.

Above all, in spite of it all, there are still many worse ways to go through this life.

Watch the trailer for Long Strange Trip

The Dead’s enormous catalog and merch are available here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationWow. I was on the fence about seeing this in the theatre (As opposed to waiting for it on Amazon) but this review won me over. Thank you!

I have no doubt it’s going to make me a bit sad. By the early 90s, it was clear the band — Garcia in particular — was struggling. By 1994 I’d decided I’d had enough with the increasingly out of control circus.

But the Dead left behind — And the surviving members continue to bring — a lot of joy as well. The music confinues to inspire me, so I owe it to myself to see this film on the big screen.

I definitely recommend seeing it in a theater. The sound mix is pretty great.

That’s why, ultimately, even with all the rare live footage and insightful interviews, this is as much a film for people who admire the work of Bar-Lev as it is for people devoted to the Dead. In his films