On July 29, 1966, Bob Dylan was traveling near his home in Woodstock, N.Y., when he crashed his Triumph Tiger 100 motorcycle, reportedly damaging several vertebrae in his neck. No ambulance was called, and he was never hospitalized; most details were kept from the media. In his autobiography Chronicles Dylan admitted he’d “been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.” He settled down to a domestic life with his wife and kids.

On July 29, 1966, Bob Dylan was traveling near his home in Woodstock, N.Y., when he crashed his Triumph Tiger 100 motorcycle, reportedly damaging several vertebrae in his neck. No ambulance was called, and he was never hospitalized; most details were kept from the media. In his autobiography Chronicles Dylan admitted he’d “been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.” He settled down to a domestic life with his wife and kids.

His high-powered manager Albert Grossman was forced to accept Dylan’s withdrawal from live shows and recording sessions, but to keep income flowing Grossman decided to quietly spread around demos of more than a hundred songs Dylan had never issued commercially himself, some of which were recently done with his backing band the Hawks, who were living in a nearby house nicknamed “Big Pink.” Several songs became hits, including Manfred Mann’s “Mighty Quinn,” the Byrds’ “You Ain’t Going Nowhere,” Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Too Much of Nothing” and (in England) “This Wheel’s On Fire” by Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger and The Trinity and a French-language version of “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” by Fairport Convention. Dylan’s songs could work in the marketplace even when he refused to show up.

Joan Baez, who had been in Dylan’s inner circle for many years, both as an off-and-on romantic partner and musical cheerleader, decided to tackle an entire album of these new and neglected Dylan compositions for her label Vanguard, decamping to Nashville’s CBS studios in the fall of 1968. The cream of Music City’s “session cats” were assembled, including Pete Drake (steel guitar), Fred Carter Jr. (mandolin), Kenny Buttrey (drums), Norbert Puttnam (bass), Hargus “Pig” Robbins (piano), Johnny Gimble (fiddle) and guitarists Jerry Reed, Jerry Kennedy and Grady Martin, who also served as band director. (Stephen Stills is also listed in the liner notes, but like all the instrumentalists there’s no identification of exactly what he played on.)

Many of the musicians had joined Dylan on the Blonde on Blonde sessions at the same recording studio, and delivered once again for Baez and her producer/label-owner Maynard Solomon. The double-LP issued a few months later in December, Any Day Now, “went gold,” reached #30 on Billboard’s Pop Album chart, and yielded a radio hit with “Love Is Just a Four-Letter Word.” The sessions were so fruitful they even provided the contents of her followup, David’s Album, released a mere six months later.

Related: Joan Baez on Dylan and more

For many, Baez’s relationship to Dylan as a person and songwriter was and is difficult to understand. As she wrote in the notes to her Rare, Live & Classic boxed set, “Performing with Bob Dylan was electric, especially during the early years. He had a reverse charisma that attracted me, the way he pulled away. I was the exact opposite, but there we were together. It was tension-provoking. The audiences were wild-eyed at the whole mythology of it all.”

Any Day Now begins with “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” originally heard on Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home LP. The arrangement relies heavily on the Danelectro electric sitar, previously featured on the Box Tops’ “Cry Like a Baby” and the Lemon Pipers’ “Green Tambourine.” Paired with steel guitar midway, it provides a truly unusual atmosphere, along with the light-touch drumming and shining acoustic guitars. Baez’s voice is crystalline, her articulation of the complex lyrics perfect, as she backs off a bit from her powerful vibrato. The recording announces that this will be an album of experimentation and country-inflected details, totally different from her mid-1968 release Baptism: A Journey Through Our Time.

The dobro (played by either Harold Bradley or Harold Rugg) leads a loping, beautifully loose version of “You Ain’t Going Nowhere,” which also features a lovely fiddle section from some combination of Buddy Spicher, Tommy Jackson and Johnny Gimble.

Baez performs equally authoritative versions of previously heard Dylan songs from well-known LPs (four from The Times They Are A-Changin’ and the epic “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” from Blonde On Blonde), but the core of Any Day Now consists of songs that wouldn’t see the light of day until Dylan’s subsequent album John Wesley Harding and the Band’s Music From Big Pink. “Drifter’s Escape” (more excellent dobro and some very snazzy drumming) and a piano-led “I Pity the Poor Immigrant” conclude side one of Any Day Now. Baez’s vocals are wonderfully emotional, handling both uptempo romp and ballad: is it blasphemy to suggest she sings both better than their author does?

Baez audaciously handles “Tears of Rage” a cappella. Written by Dylan with the Band’s Richard Manuel, the Music From Big Pink version is a masterpiece, but Baez’s take is astonishing, jaw-dropping, pick-your- superlative. The note she strikes on “thief” should be enshrined in a vocalist’s hall of fame.

The 11-minute “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” has a plethora of delicate instrumental touches, and Baez brings a different kind of feminine melancholy to the words, providing a fitting twin to Dylan’s own reading. Those two songs fill an entire LP side with non-stop brilliance.

Side three of the LP set begins with “Love Is Just a Four-Letter Word,” a song Dylan never performed live or issued on disc, and which can be seen being purloined by Baez before it’s even finished during Dylan’s 1965 British tour in the documentary Don’t Look Back. The Danelectro returns in an arrangement that straddles the country-pop borderline. It deserved to reach much higher than #86 on the Billboard singles chart. Vanguard wasn’t known to have the necessary pop music marketing muscle, but it did manage to give Baez her only top5 hit a couple years later, when “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” got to #3 in Billboard when pulled from her final Vanguard album, Blessed Are. . .

Two more eventual John Wesley Harding tunes, “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” and “Dear Landlord,” are premiered on side three. Baez doesn’t sound completely at ease with either: the first has a somewhat bland vocal that sounds like a first take, and the folk-rock arrangement for the second seems a bit too kitschy in 2022. The waltz “Walls of Red Wing” suits Baez better, with fiddle and pedal steel out of the Texas dancehall tradition, and piano work that echoes the Nashville icon Floyd Cramer. Dylan recorded it twice during 1963 and rejected both versions; the take from the Freewheelin’ sessions was eventually released as part of the first Bootleg Series volume in 1991.

Another Any Day Now highlight is “I Shall Be Released.” Baez swoops around the melody exuberantly, and adds a gospel flavor with an overdubbed chorus. It’s quite different from the way Richard Manuel sings it on Music From Big Pink. This was the only song from Any Day Now that Baez chose to perform during her set at Woodstock on August 16, 1969, at 1:30 a.m., and her live version there is even better.

Baez handles the novelty tune “Walkin’ Down the Line” well enough, but it’s certainly minor Bob, originally performed by Dylan for Broadside magazine in 1962 and as a publishing demo the following year. It was recorded by others about a dozen times before Baez tried it on; she fails to wring as much humor out of it as Arlo Guthrie did when he sang it at Woodstock, sufficiently stoned.

“Boots of Spanish Leather” and the concluding “Restless Farewell” are truly magical, with two of Baez’s best vocals. She places “Restless Farewell” as the final album track just as Dylan did on The Times They Are A-Changin’, but it’s another case where the pupil exceeds the master, not in world-weariness (Dylan’s got a lock on that) but in beauty of expression and lyrical power.

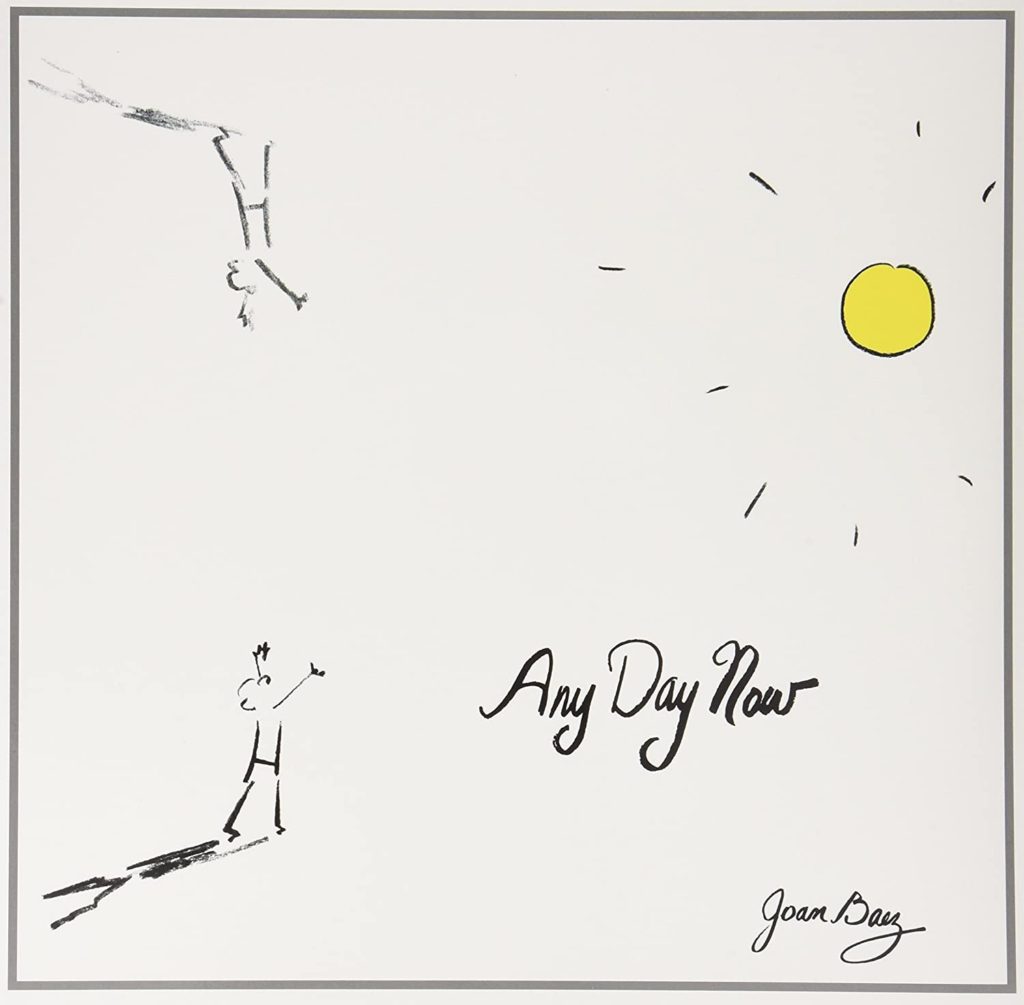

Baez drew the fanciful line drawings that grace the cover and inner gatefold of the double-LP, taking the album title from the stirring chorus of “I Shall Be Released.” When her days as a Vanguard recording artist ended, she began a fruitful association with A&M Records, yielding one of her rare self-penned songs, “Diamonds & Rust,” a look back at her relationship with Bob Dylan and the Greenwich Village scene.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Diamonds & Rust

Baez, born January 9, 1941, continues as an influential activist and musician, her integrity and voice intact. Any Day Now is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Baez reprise her cover of Dylan’s “Love is Just a Four-Letter Word” for Martin Scorsese’s documentary No Direction Home

Related: Our review of the 2024 Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationBack in the late 1960s, I renewed Any Day Now several times at our local library.

Apart from 4 Letter Word, and SELOTLowlands, she successfully butchered all the other songs.

Interesting piece, however, John Wesley Harding was released more than a year before Any Day Now.

When it comes to guitar prowess in the Folk Music genre .. Joan Baez has no superiors and very few peers .. her style is all her own and is completely delicious .. Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul and Mary fame on guitar is also in the same zip code as Joan musically .. Donovan and Arlo Guthrie deserve to be mentioned as well ..