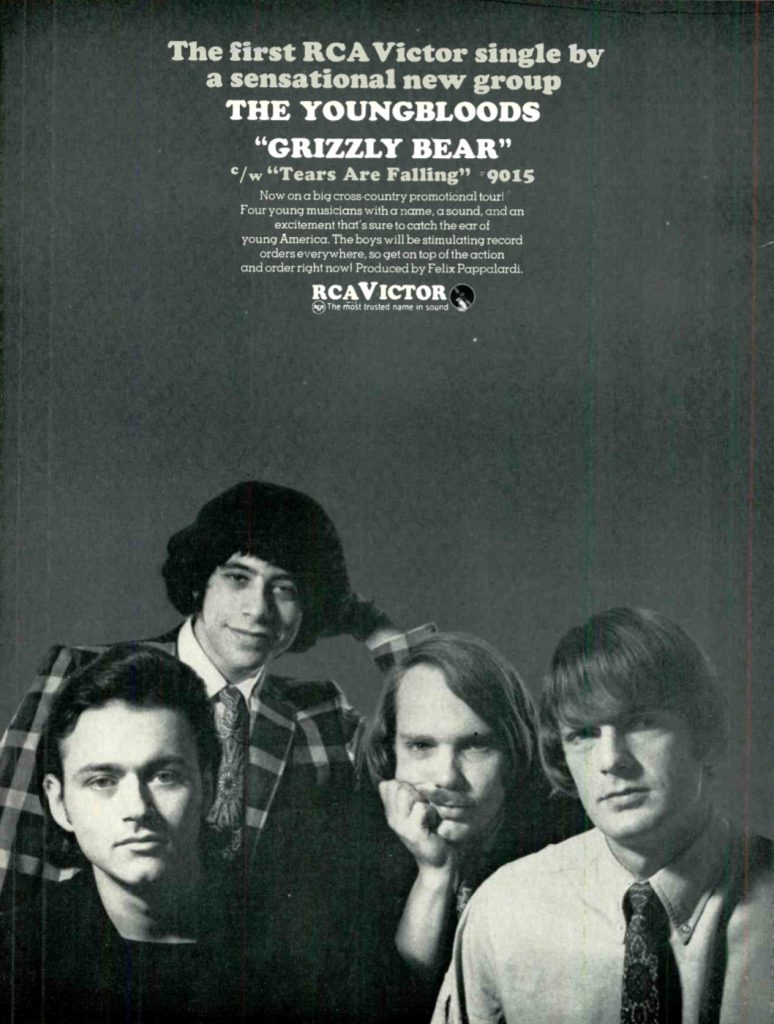

The Youngbloods in 1967 (l. to r.): Jesse Colin Young, Jerry Corbitt, Joe Bauer, Lowell “Banana” Levinger.

As far as choruses go, few are as instantly identifiable as this one: “Come on, people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another right now.”

The song, “Get Together” (sometimes called “Let’s Get Together”), has a fascinating, convoluted history that you can read about here. For most people, it will always be associated with the Youngbloods, whose primary lead singer, Jesse Colin Young—born Perry Miller on Nov. 22, 1941 in Queens, N.Y.—got his start in the early ’60s as a solo folk-blues singer on the Boston-Cambridge club circuit. He released two acoustic albums, The Soul of a City Boy (Capitol Records, 1964) and Young Blood (Mercury, 1965), before the rock and roll bug bit him.

Along with guitarist-singer Jerry Corbitt, keyboardist-guitarist Lowell “Banana” Levinger and drummer Joe Bauer, Young (who switched to bass in the band) formed the Youngbloods in Boston in 1966 and, after signing with RCA Records, they recorded their self-titled debut album the following year. Produced by Felix Pappalardi, who would also produce Cream around the same time and later join Mountain, the folk-rock album, which bore a resemblance to the sound of the Lovin’ Spoonful, only rose to #131 on the national charts. A single taken from the album, “Get Together,” credited to Chet Powers (who was actually future Quicksilver Messenger Service singer Dino Valenti), stalled at #62. The Youngbloods’ sophomore LP, Earth Music, in the same vein musically, didn’t make the charts at all.

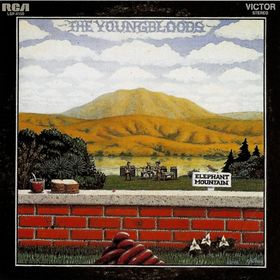

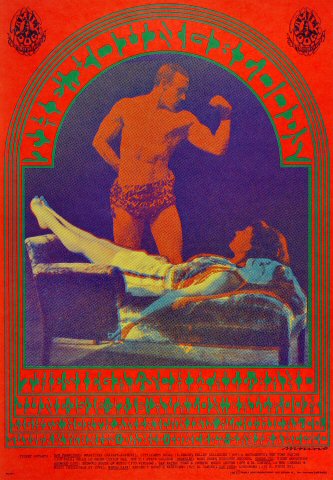

Clearly, they needed a change if they were to survive, so in mid-’67, the band yanked up its roots and relocated from its then-current home of New York City to the San Francisco Bay Area. There they found greater acceptance among the local rock aficionados, and set out to make their third album for RCA, which would be titled Elephant Mountain (named after an actual peak near Pt. Reyes Station in Marin County, north of San Francisco, where the band, now reduced to a trio with the departure of Corbitt, resided). With Charlie Daniels producing, the album, despite its underwhelming chart performance, gave the Youngbloods a large credibility boost—today it is considered not only the band’s finest but a sleeper classic of the era, with jazz-informed songs like “Ride the Wind,” “Sunlight,” “Darkness, Darkness,” “Quicksand” and “Beautiful” receiving massive amounts of airplay on the FM rock stations of the day.

Even while they were moving forward, the Youngbloods experienced a surprise hit when “Get Together,” from the debut, was re-released in the summer of ’69. This time it resonated with the larger audience, finding its way to #5 on the Billboard Hot 100.

With that success in hand, the Youngbloods were able to launch their own Warner Bros.-distributed label, Raccoon Records. They released their next album, a live set called Rock Festival, in 1970, followed by a second live set, Ride the Wind (1971), Good and Dusty (1971) and High on a Ridge Top (1972). By that time, the band members (including bassist Michael Kane during the last couple of years) were ready to go off on their own.

In the first half of this two-part interview with Jesse Colin Young, the singer-songwriter-musician discusses his early years and his time with the Youngbloods. In part two, soon to follow, he talks about his post-Youngbloods solo output, including his brand new album Dreamers, his first set of new studio-recorded material in more than a dozen years.

Best Classic Bands: You’re usually categorized as a West Coast artist so a lot of your fans probably don’t realize you were originally from the borough of Queens in New York City. Did you do any singing when you lived there?

Jesse Colin Young: I did a lot of singing in Queens until I was 10, but it was around the piano with my sister and my mother and my dad playing. Then we moved to Garden City on Long Island. I was playing the piano and they were teaching me all these stupid songs, so I quit when I was 11, as soon as I got into doo-wop. If I’d had a teacher who taught me how to play the four amazing chords that made up most of the songs in those days, I would have stayed with it. But instead I just became a record collector and my own disc jockey. That went on until I went to Andover [Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass.] and they offered guitar as an elective. I took it and learned to play and my roommate took it, and pretty soon we were we were harmonizing like the Everly Brothers but not quite as good. We were both learning and we both had these terrible Stella guitars. But I fell in love [with music] and I started to write. I made my first record there. I recorded Elvis’ “Trying to Get to You” on this machine they had that would actually cut a single record. I brought my guitar and my amp. It all went into one mic and came out on a record. I wish I still had [the record].

You were very influenced by the blues.

JCY: Yes. I got kicked out of Andover before I graduated for playing the guitar during study hours, and I went to Ohio State [University] and moved into an apartment behind a record store. There I discovered [blues guitarist-singer] T-Bone Walker and that changed my life. The owner of the store allowed me to tape the records. This was before shrink-wrap. My dad had bought me a tape recorder and I taped T-Bone and then we brought the record back and put it back in the racks for somebody else to buy. So, he didn’t get any royalties for me—sorry, T-Bone! Arif Mardin produced the most interesting cuts and then there were a few filler ones that were produced by somebody else. It was a great record. It had “Stormy Monday.” I still do [Walker’s song] “T-Bone Shuffle” in the show, but “Stormy Monday” was the one that, when I quit school, I quoted to the dean of men. I said, “They call it Stormy Monday, but Tuesday’s just as bad.” I said, “There’s more wisdom in those two lines than I’ve had in my six courses in my year and a half here. I think I have to go to the school of the blues.”

Listen to “Four in the Morning” from Jesse Colin Young’s debut solo album

Your first two albums were acoustic recordings. Then you put the Youngbloods together with Jerry Corbitt. Where did you meet Jerry?

JCY: I met him in in Cambridge [Mass.]. I was staying with someone there and I was having a soundcheck at Club 47. I got this message from Corbitt that said, “Don’t go home to Ed Freeman’s house,” where I was staying. Ed had bought some pot from a Coast Guard undercover guy and got busted. So I went to Corbitt’s house instead. Then I always stayed with Corbitt and we started playing together on his back porch and he started showing up at my gigs—Boston and Cambridge had more venues than all of New York, so I played there a lot. Then one day after the Beatles came out we said, “Could we just transition into a band?” Banana lived down the street from Corbitt, and Joe Bauer had just come up from Memphis and moved in upstairs from Banana. There weren’t a lot of drummers around, because the folk thing was pretty strong. Pretty soon I was playing duo and then we were Jesse Colin Young and the Lonely Nights or the Jerry Corbitt Three. We had a bunch of names before we got around to Youngbloods.

After a while the Youngbloods moved down to New York. Why?

JCY: We were one of two opening acts, the Blues Project and the Youngbloods, at the Cafe Au Go Go for nine months. I got to open for Muddy Waters. That was a big event in my life. James Cotton was in the band; Sam Lay was playing drums. And of course Muddy, with that voice that just takes you to Mississippi—even though you don’t want to go there. What a band!

Related: What was happening in music in 1967?

You found “Get Together” through [singer-songwriter] Buzzy Linhart, right?

JCY: I walked into the Go Go on a Sunday afternoon, thinking it was dark. I was going to call up the guys and say, ‘Come on, we can rehearse.” We didn’t know what we were doing; we were making a band up out of a bunch of mavericks and folk singers and a jazz drummer. We needed a lot of work. So I walked down the stairs and there’s Buzzy. I had seen him play vibes with Tim Hardin, but I’d never heard him sing and there he was singing “Get Together.” I just rushed backstage and said, “I gotta have the lyrics, please, please,” and he wrote them out for me right then. I must have memorized what Buzzy was singing for lyrics and it was pretty easy to figure out the chords. I took it into rehearsal with the Youngbloods the next day. I was in love with it and I still am. The worse things get, the more powerful “Get Together” is, and the hungrier people are to sing it.

Related: Linhart died in 2020

The Youngbloods’ second album was Earth Music and then, during the 1967 Summer of Love, you all moved to the West Coast. What was the reason for relocating there?

JCY: It was June 15th, 1967. We played the Avalon [Ballroom, in San Francisco] and it was full of freaks and they all looked like Banana with the big hair. So we realized we could work there. Then we walked into this cheap motel and there’s this funny little radio built into the bed and I turn it on and there’s “Get Together.” Wow! We were past starving in New York. Discos were happening; we even played with the Buffalo Springfield at a disco. It was really kind of weird. But people loved “Get Together” in the Bay Area and we realized we could work there.

We went home, finished Earth Music and then packed up and moved. When the time came for Elephant Mountain we had been on the West Coast for a year.

Charlie Daniels produced that album. What was he like?

JCY: You should have seen Charlie in a rayon suit with short hair and milk bottle-bottom glasses. He was a perfect producer. He explained it to me. He said, “Sometimes artists need you to get behind them and push them, and then other times you get in front of them and hold them back, but I think you guys just needed me to be there.”

The band became a trio at that time. What happened to Jerry Corbitt?

JCY: Three tunes into the Elephant Mountain album, Corbitt left the band. He said, “I can’t fly anymore.” Here we are at the beginning an album; we were recording in L.A. at RCA Studios. So we just carried on and Charlie was the transition. He was always in a good mood, always ready, always appreciative and supportive. He got us through it.

Watch the Youngbloods perform “Get Together” and “Sunlight” on The Hollywood Palace (hosted by Milton Berle)

That same year, “Get Together,” from the first album, came back to life and became a huge hit. Did that surprise you?

JCY: I became friends with Augie Bloom, who was the head of promotion at RCA. He may have told me, ‘We’re going to wait till the country catches up with San Francisco and then we’re going to release this record again.” He made it happen. He went to [RCA] and said, “Either you re-release ‘Get Together’ or you can look at my back walking out the door ’cause I’m out of here.’ He was way too good for them to let him go. Record companies usually don’t re-release the same song, the same version. But it was perfect. Augie knew it would happen.

Eventually, the band built up a big following in other places, particularly the East Coast, where you played venues like Fillmore East. Were you aware that this was happening after you left New York?

JCY: A little bit. We made most of our money in colleges in the east. We’d fly in for the weekend and do three-day gigs, and then fly home. We brought our whole PA with us. We had these two crazy hippies who were kind of tour managers and they would drive that PA out onto the runway at United Airlines in San Francisco and throw it in the back of a 747 or 737, whatever we were flying in those days, for free. United let us do that. We’d pull it out, put it in a rented truck and then go play three colleges and then go home.

Related: 10 songs that became hits when re-released

After Elephant Mountain, the Youngbloods added a bass player (Michael Kane) and made a series of albums, both live and studio, for your own Raccoon label and RCA. Do you have any favorites among those?

JCY: Not really. Some of them were interesting but I think I was beginning to get bored and I wanted to be in a band more like The Band. I was yearning. Those grooves were so funky, and if there’s one thing the Youngbloods probably weren’t, it’s funky.

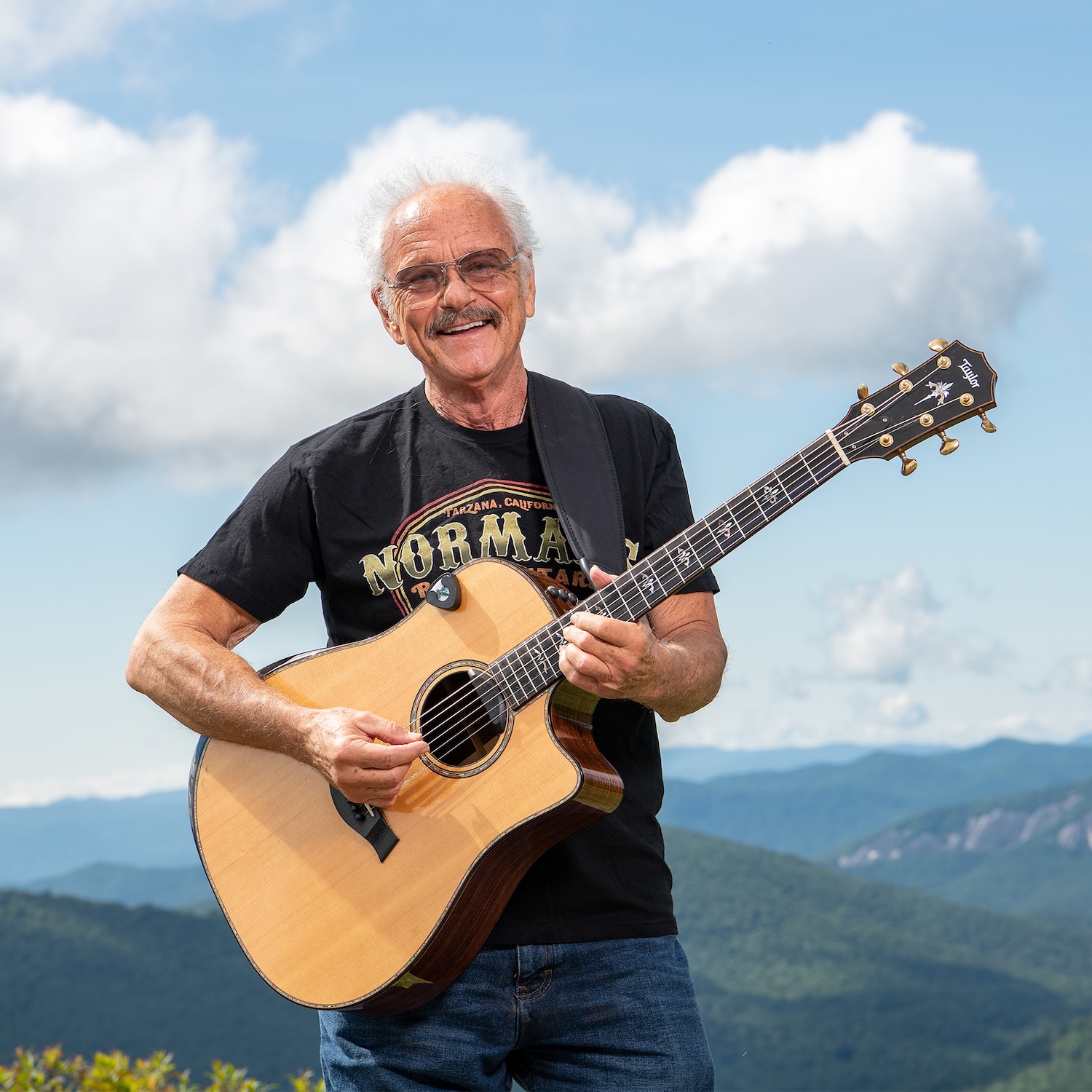

Jesse Colin Young in 2020

Young died on March 16, 2025.

[The Youngbloods’ recordings are available here. Many of Young’s solo albums are available here.]

Listen to the Youngbloods perform “Ride the Wind” in 1969

7 Comments so far

Jump into a conversation1967 at Newport folk festival. Saturday afternoon hanging out in the parking lot with a group of freaks listening to Jesse, Jerry Jeff, and David Bromberg who were sitting on the tailgate of a pickup truck giving a discussion on what they do. I heard a familar voice behind me and turned around to see Muddy Waters standing behind me. As I remember he looked like he did on Electric Mud. He was gracious and spent a couple of minutes talking to this whiteboy from Vermont. I was in heaven.

I sang with Jerry Corbett for two summers nightly at a bar in Hyannis on Cape Cod. I have no idea where Jesse got some of these stories about Jerry. We all were together on Labor Day Weekend at a club in Martha’s Vineyard and decided to take ourselves as a group to sing in New York. I opted out as I decided to go back to Cleveland and finish law school. They went to New York and became the Young Bloods. The story of how Jerry left the band was also not true, at least according to him. I, however, will not get in to the sordid details.

2 corrections. Joe Bauer never played bass. Also, Raccoon Records was distributed by Warners, not RCA. Otherwise, a good article!

Thanks for the correction on Raccoon. We’ve made the fix. Nowhere in the article does it say Joe Bauer played bass, however.

Great article.

That’s David Lindley playing the fiddle on “Darkness, Darkness”. For years, I had assumed it was Charlie Daniels.

I saw the trio version of The Youngbloods. They were a great live act.

Jesse was supposed to play at my upstate NY college around 1970, but he had to cancel. His wife was about to give birth. His substitute was Frank Zappa and the Mothers.

Sort of “Come on plastic people…”

There was a Rock Festival in Washington State in the early 1970’s called “The Satsop River Fair and Tin Cups Races” … Delaney and Bonnie, Wishbone Ash, some regional brands and The Young Bloods all played it .. Ike and Tina were spoze to play too but never showed up .. The band I was in at that time was called “Gunther Haydees” (we were completely unknown and still are) .. we knew a couple of bands who were going to play there .. so .. we packed up our gear and headed on down from Seattle … keep in mind this was the early 1970’s so we all still believed in miracles (and I still do) … When we got there it was complete pandemonium .. no one knew who was in charge, so I just strolled in like we were on the roster to play as well as a couple of names of other groups that actually were on roster … so .. we drive 3 vehicles into the back stage area .. some jackass who claimed to be in charge … I believe his name was “Moon Eagle” if memory serves me corrrectly balked at letting us back there .. so .. I explained that we also had all the equipment for one of the bands and just get out of the way .. with in an hour we were in charge of the helicopter field and wound up being camped close to where the Youngbloods were camped … I had a few conversation with Jessie and Banana I love good people and they were great .. not conceded spoiled ego tripping stars .. just plain good folks. The Youngbloods played brilliantly that evening .. “Darkness, Darkness, “That Was The Other Side Of His Life” and “Get Together’ all brought approx. 120,000 raving fans to their feet .. they had a great version of “Pontiac Blues” and “Grizzly Bear” too .. Lowell “Banana” Levenger has a guitar shop in Northern California somewhere and I heard a while back that Jessie moved to Hawaii and was selling some hi-bred coffee .. R.I.P .. JCY .. you left an indelible mark on the music scene of the late 1960’s to mid-1970’s .. Well Done old friend .. and rest easy.