Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane on Alternate Quantums and Nude Mud Love-Ins

by Harvey Kubernik

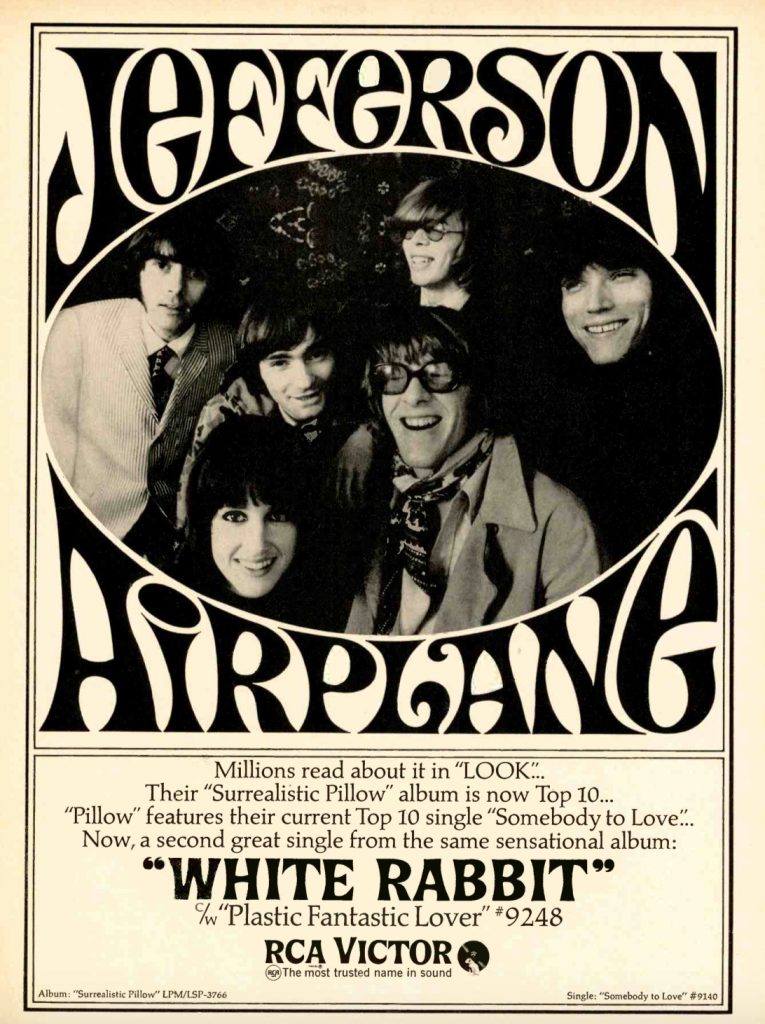

Jefferson Airplane, late 1966. Top row, l. to r.: Jack Casady, Grace Slick, Marty Balin. Bottom row, l. to r.: Jorma Kaukonen, Paul Kantner, Spencer Dryden. (Photo by Herb Greene, from the album cover of Surrealistic Pillow)

Over four decades, music journalist and author Harvey Kubernik interviewed Jefferson Airplane and Jefferson Starship cofounder Paul Kantner—both bands’ rhythm guitarist, singer and songwriter—numerous times. Kantner, who was born in San Francisco on March 17, 1941, and died in that same city on January 28, 2016, was always insightful, often outspoken and sometimes quite outrageous.

The snippets that follow are Kantner’s responses to various questions, culled from their dialogues in California. No need even to know the questions; his words stand alone. (Editorial additions are included in brackets.)

Jefferson Airplane had the fortune, or misfortune, of discovering Fender Twin Reverb amps and LSD in the same week while in college. That’s a great step forward. One of the reasons I started a band was to meet girls. And to this day it beats giving guitar lessons at a guitar store. I did that, too.

As Jefferson Airplane we had played at the Monterey Jazz Festival [1966]. We were invited because we were the new hip band. They were stretching out that year, which was the nature of the times. Thank God what a great nature that was. When we played the Monterey Jazz Festival, [jazz critic] Leonard Feather wrote that we “sounded like a mule kicking down a barnyard fence.”

Related: When Jefferson Airplane sang from a NYC rooftop

By the time we did the Monterey International Pop Festival [1967], we had a record deal with RCA and an album out that we recorded in Hollywood. Years before, I had a house in Venice with [David] Crosby and [David] Freiberg. Crosby is my friend. I hung out with the Byrds before I even started a band. That was fun. I always played an acoustic 12-string as a folkie, so it was just a natural switch over to the electric Rickenbacker.

The nature of our whole band is six very different people, musically and personality-wise. [Bassist] Jack [Casady] wasn’t so much a blues player as an orchestral something or other. [Lead guitarist] Jorma [Kaukonen] was blues: Rev. Gary Davis. Grace [Slick] was Grace. [Singer] Marty [Balin] was Marty, from show biz. We were very different people. By Monterey [Pop], [drummer] Spencer Dryden had replaced Skip Spence. [Spence] was an amateur guitar player, and we needed a drummer, and he just wanted to be in a band. “I’ll be the drummer.” He had a good energy to him, although he wasn’t disciplined. Spencer, on the other hand, was very jazz-oriented and knew a lot of licks. Neither of them was the drummer I would want. On the other hand, they were, if you know what I mean. It worked out pretty good. So, who is to complain?

We went into it our normal selves. That’s why I like to leave ourselves open and that’s why we did Monterey. We did not know what was going to happen, and there was all that L.A. stuff versus San Francisco. I didn’t pay any attention to it. I enjoyed bands from both towns.

As far as San Francisco being suspect of L.A. and Hollywood people, we always tried to get above that, if possible, as a general rule. People [in San Francisco] didn’t like the Doors, ’cause they were from L.A. (laughs). So, there’s an immediate antipathy. I liked the Doors a lot and toured with them. I created that lack of that antipathy in myself. I rejected the suspicions of L.A. as a general rule. I thoroughly enjoyed L.A. and New York. I could make myself comfortable in either one of those cities. I liked San Francisco a lot.

FM radio was one of the many things that showed up and was going on in those days. So many things were going on, you didn’t take notice of them. You just assumed that was going on. We didn’t analyze it. We didn’t think to wonder about it. It was just another thing that was going on, along with the music, the clothes, the bookstores, the poets, the artists; there was a plethora of things, and you did not have time, basically, to take it all in. It existed. It’s part of a whole.

In San Francisco we had no restrictions. We never thought about being on an independent record label for cred. It came to us. All we had to do was roll with it. I liken it to whitewater rafting. There was so much going on you didn’t worry about what was around the next curve, or what are you going to do on the third curve, ’cause you are right in the river.

Monterey Pop was just a continuation of the [Golden Gate] park, really, for us. It was playing in the park, a little bigger and a little more organized. Monterey was a step away from that, with elements of that into a commercial event. Originally it was designed that way. I had friends at Monterey and there were bands from England, a combination of elements. I had been listening to Ravi Shankar for years, so I wasn’t waiting for him. He played a lot in the Bay Area, even during our folk days in Berkeley. Crosby was the one who brought everyone’s attention to him, for whatever that’s worth. David was out of the folk mode of the early ’60s. Monterey was just a booking, another step. No one viewed it as some great momentous brouhaha. But it became more than that, as many things did in those days. It became what it became.

Watch Jefferson Airplane perform “Eskimo Blue Day” in 1970

There’s no name for what we did. It’s not rock n’ roll. It’s not folk music. I don’t know what it is. We all took up and started in folk music and then branched out. But I really didn’t get into electric amps even then. I did like the sound of the reverb, even with our acoustic guitars and stuff. I liked Crosby’s tunings.

At Monterey Pop, what Janis did, I saw her do that every night. She used to play in clubs around town. Probably the reason that Janis died was that she got too popular and left her band. To her credit, Grace didn’t leave the band and probably survived as a result. There’s a big difference between the two. Grace got, as you can imagine, all sorts of offers to go solo. On one level she didn’t feel confident enough. On another level she didn’t want to leave the band the way it was.

At Monterey, we did what we wanted to do. Grace spent a whole year not doing “White Rabbit,” if I’m not mistaken. I had seen Grace do “White Rabbit” with [her earlier band] the Great!! Society!! I just liked Grace as a singer and the band overall. I saw them playing [the song] down at a club on Broadway, actually. I liked Grace from the very start. I thought she had something. We did “High Flying Bird” [written by Billy Edd Wheeler and first recorded by Judy Henske]. [Early Airplane singer] Signe [Anderson] drove that song well. The song carries itself. The idea is that songwriters should write good songs.

We had a lot of songs. We did Fred Neil’s “The Other Side of This Life,” [the Darby Slick-written] “Somebody to Love.” I’m still not tired of playing it. I’m still fascinated largely by the metaphysic, if you will, of the music itself, why it affects people the way it does. How such a relatively simple combination of elements, be it a large orchestra, or a simple three-piece rock ’n’ roll band, is able to communicate emotion to people. That connection still remains a mystery to me. We play it live every night, and I don’t need to find out the why of it. If I do, it might ruin the whole thing. But being able to manipulate it as we do is always fascinating to me.

Watch the Airplane perform “High Flying Bird” at Monterey Pop

[The Surrealistic Pillow ballad] “Today,” Marty and I worked up together. We wrote several things in those days. He’d bring a piece, and I’d bring a piece and we’d put them together and weave them. And they fell together in the studio. [Jerry] Garcia played on the track in the studio. When we took it out on stage and did it with our group, it became piano-driven.

Quicksilver Messenger Service was quite good. [Guitarist] John Cipollina was an unusually unique guitarist. He created his own distinct sound. Too bad he’s gone. In all the bands that came out of San Francisco, not very many people were good singers. We had the luxury of having both Grace and Marty in our band, who were both excellent, just the texture of their voices. Very attractive. David Freiberg has a voice that is very on, powerful, clear and ringing, very sonic.

Why did I have a guitar? It was one of the things that was there. We just played and never thought of it as good or bad. Even without the light show we still had really good music, singers and songs. The light show was just an added enhancement where we could get it involved, and it traveled with us after a while. Expensive.

I enjoyed [Jimi] Hendrix and Otis Redding at Monterey. Jimi was impressive. You can’t define it. You don’t have to. If you saw it, you knew what it was. The Who were OK. I’ve never been knocked out by the Who too much. I liked their one song “I Can See for Miles.” That’s a beautiful song. Generally, I don’t like guitar heroes too much. They play too many notes, too fast and too long. What’s the point? I’d like to hear a melody and people who could play great lines. Cream did in their early days; they did some great guitar work and were a great band.

Moby Grape was a good band, and Skip [Spence] was in his element in that band as well. That’s what Skip always wanted to be. Unfortunately, with us he was the drummer, so he couldn’t be up in front of the stage being so joyful, which he was. He was a character.

[Fillmore East and West promoter] Bill Graham had all these strange combination of acts on the bill. We didn’t think of them as opening acts. We just thought of them as other acts that are really good. We encouraged Bill to book those kinds of bookings. No chains. That was what was so glorious about San Francisco in those days. A lot of people f**ked things up, took it too far. Those big, huge gatherings were not very interesting.

Watch: Altamont 1969: When things turned nasty, Kantner let the Hells Angels know his thoughts

The reason that people came to the Fillmore was not the band. People came to the Fillmore much like a harvest festival, to be there. If there were good bands playing, that was an added plus. But not many people were coming as fans of the band. We got away with it all, more or less. Mostly. You went to the park, the Fillmore, Monterey, to get absorbed in the whole whatever it was going on.

The point is, if you find something that makes you joyful, take note of it, amplify it if you can. Tell other people about it. That’s what San Francisco was about, musically, idealistically and metaphorically and every other way. That’s what we did here. We were in a place that encouraged and nourished that kind of thinking and still does to this day, and we took full advantage of it. We weren’t up on soapboxes complaining like the Berkeley people. We need those people too. Those people are very valuable, but that’s not what we did. Our message was subtler. There was a message there, but we didn’t blare it out. We just tried to show by example what you could get away with, basically. We tried to propose a real alternate quantum, and did. Enjoying our day. That’s all we tried to put across. Hedonistic or Dionysian on some levels. That existed.

San Francisco was very good, I think, particularly the musicians, at transmitting the goodness of the day, rather than complaining about the badness of the day. Creating another universe, if you will, or at least a semblance of another alternate quantum that worked for us. And God knows why we got away with it 90 percent of the time if not more. We should have been in jail, dead, run over by trucks and a number of things over the years.

Jefferson Starship in 1975. Back row, l. to r.: Pete Sears, Paul Kantner, Grace Slick, John Barbata. Front row, l. to r.: David Freiberg, Marty Balin, Craig Chaquico

I like bouncing ideas off people who like to work together. There’s a little magic in a band when people decide to put their heads and minds to one thing, and it works. It becomes more than the people involved. With the Airplane, we thought we could do it all. It was a reaction against the corporate structure trying to impose certain limits on you. We revolted against that, which was the other extreme, which is doing it totally ourselves. And it was like putting a five-year-old in an automobile reeling down the street. It may make it down the street, but the car may get a few dents along the way. Mistakes become part of the arrangement, as jazz people used to say. Or as Jorma used to say, “When you make a mistake on guitar, repeat it. Everybody thinks it’s part of the arrangement.”

On our earlier songs, like [1968’s] Crown of Creation album, it was sort of a comment on the state of affairs, not news-driven so much as situation-driven. I wrote just regular songs and then got a little out there like we all did on [1967’s] After Bathing at Baxter’s. Still one of my favorite albums just for the stretch that went from Surrealistic Pillow to Baxter’s.

Watch Jefferson Airplane perform “Crown of Creation” on The Ed Sullivan Show

We put it out in the universe and see where it lands. Sometimes you keep a little control over where it lands, more often than not. I like things going out, connecting with other things. I’m very much on collaboration as a writer and a player. I like collaborating. I like the friction that happens and the fire that occurs as a result of that friction. There was a message there, but we didn’t blare it out. We just tried to show by example what you could get away with, basically.

On our first U.S. tour, we were in cities where all the kids came in prom gowns and tuxedos. Then we came back to Iowa a year later and they were having nude mud love-ins, and everybody had their faces painted.

Watch: When Kantner and Grace Slick turned up as unannounced guests at a 1988 Hot Tuna gig, and sang “Wooden Ships”

Author and music journalist Harvey Kubernik’s books are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationThank you Harvey for such an excellent post. As an older guy I now have the opportunity to study favorite bands in detail. I listen, I watch, I read. Back in the day of course that was impossible you simply had to experience first hand. And the more I learn about Jefferson Airplane the more I am just floored by their gifts perspective and talent. It was just a great time to be alive.