“The reason we’ve always insisted on our full names is because we consider ourselves to be two individual artists. We’re not really a classic duo in that respect.”—Daryl Hall, 2017

“The reason we’ve always insisted on our full names is because we consider ourselves to be two individual artists. We’re not really a classic duo in that respect.”—Daryl Hall, 2017

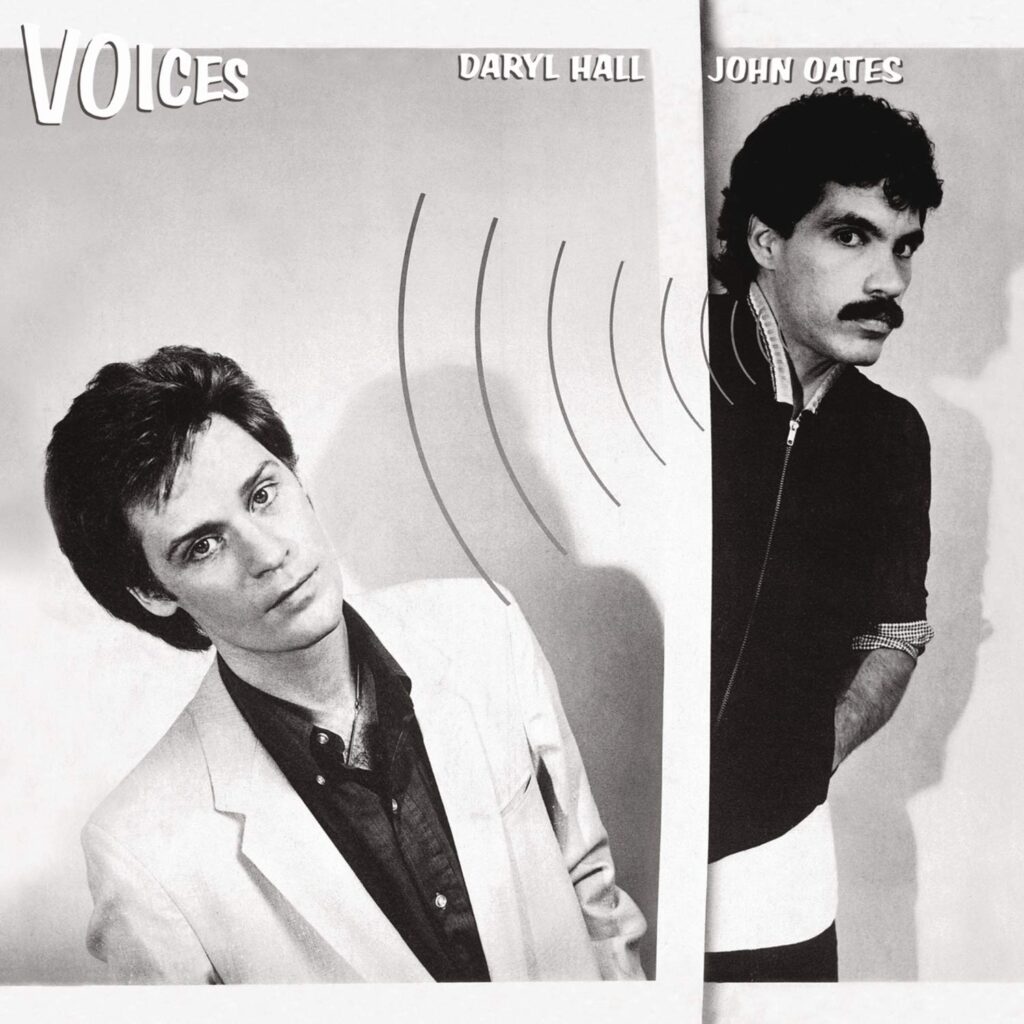

The year 1980 was shaping up to be a very fortuitous one for Philly soul duo Daryl Hall and John Oates. In the years since their 1973 breakthrough “She’s Gone,” the twosome had experienced varying commercial peaks and valleys: whether it was the misfortune of being shown as an androgynous-looking, makeup-wearing act in 1975, or a #1 hit (1976’s “Rich Girl”), or the 1979 middling success of X-Static, they’d had difficulty finding a consistent sound that could sustain their brand with the record-buying public.

Obviously, their pairing had been productive leading up to the ’80s. As the legend reads, the two met in an elevator in 1967 at the Adelphi Ballroom in Philadelphia, allegedly escaping a gang fight. Both had their own bands, but consequently left those groups, sharing an apartment and creating their own music. They first formed a musical partnership in 1970, although it took until 1972 to sign with Atlantic Records for their debut album.

Related: Our Album Rewind of the duo’s Abandoned Luncheonette

From Whole Oats in 1972 to X-Static, the two (who moved to RCA in 1974) had relied heavily on outside producers, including Arif Mardin, Todd Rundgren and David Foster. To be certain, the work was top-notch and the guest musicians throughout those years—George Harrison, Robert Fripp, Leland Sklar and Hugh McCracken among them—formed a stellar constellation of craftsmanship. And while X-Static’s AOR-harmonious “Wait For Me” peaked at #18 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in late autumn 1979, the new year would bring about stratospheric changes that neither Hall nor Oates could foresee as the decade began.

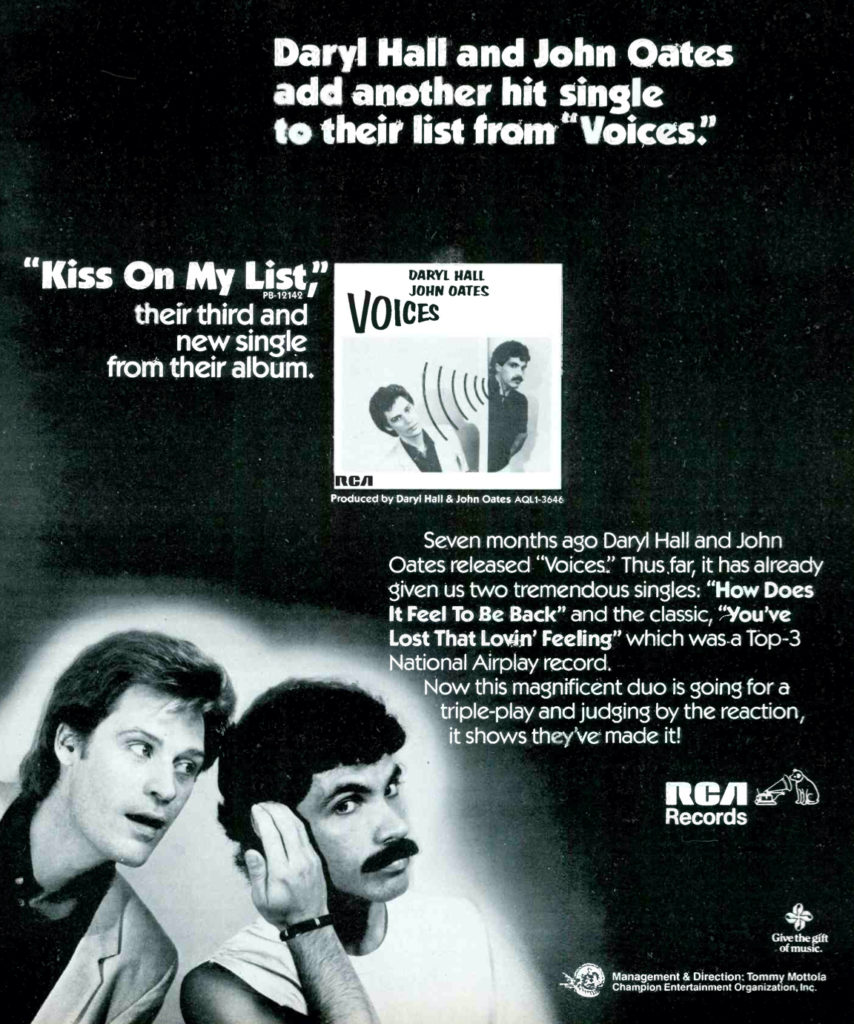

This ad for one of two Hall and Oates singles to reach #1 that year appeared in the Jan. 31, 1981, issue of Record World.

Voices’ most immediate departure was the key change in production personnel. Those duties rested squarely on both for the first time in their career, and their dissatisfaction with previous efforts in Los Angeles led them back to their home base in New York City’s Hit Factory and Electric Lady Studio. They also enlisted U.K. engineer Neil Kernon, a fruitful collaboration that would see them through the rebirth of their career and the next three albums.

But chief among the seismic shifts was the recruitment of musicians with whom they felt a kinship in the studio and later, on the road: guitarist G.E. Smith and saxophonist/pianist Charlie DeChant began their long association with Hall and Oates during Voices, while bassist Tom “T-Bone” Wolk and drummer Mickey Curry came in during Private Eyes in 1981. Hall’s partner Sara Allen, who had been working with him since the 1975 self-titled album, brought along her sister Janna, whose songwriting contributions would prove to be the secret ingredient on the 11-song tracklist.

The opener (and first single), “How Does It Feel to Be Back,” was an Oates-penned number, and he also served its lead vocalist. On the surface, it continued the tried-and-true formula of the pair’s previous ballads, yet benefited from Smith’s bright, stinging riffs and Oates’ jangly Rickenbacker rhythm guitar. The companion music video, presented as a lip-synced performance with cheesy visual effects, was serviceable, but did not help sales.

“Big Kids” breaks ground for the duo as they move into the new wave lane, with Hall’s vocal delivery taking on a buzzy undertone while still circling around the pop bandwagon, courtesy of crystalline harmonies, a funky bassline and lyrics (“Big kids, think they know it all/Big kids, think they’ve got the world up against the wall”) that relied less on a romantic entanglement and more of an “Us vs. Them” theme that would come back to the forefront with 1984’s “Adult Education.”

The album’s third track, “United State,” doesn’t waste any time, jumping off with a riff reminiscent of period Blondie, halfway into punk (the duo was living at the time in New York City, with the recording studio right around the corner). While the song’s melody clipped along, the lyrics were a little over-the-top, trying too hard to compare the U.S.A. to relationship equality: “Make an amendment to the constitution/To preserve the state of our union/Stop believing what you say to me/There’s a tragic gap in credibility.”

“Hard to Be in Love With You” can come off as merely a continuation of “United State,” but upon closer inspection, it foreshadows the direction and tone that the pair would be taking in future releases. Hall takes much of the lead vocal while Oates answers back, as the melody escalates and their vocal delivery meshes in uniform through distinctive and clever studio layering. Smith’s guitar is beginning its venture into now familiar-sounding territory that would eventually coalesce in the next release, 1981’s Private Eyes.

What can be said about “Kiss on My List” 45 years on? A collaboration with Janna Allen, Hall’s bright keyboard opening, coupled with his clear-throated Philly soul delivery, a synthesized melding of Oates’ angelic chanting and clever wordplay (“If you want to know what the reason is/I only smile when I lie, then I’ll tell you why”) gave the song its unmistakable hook. As Voices’ third single, “Kiss on My List,” released in November, went on to spend three weeks at #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and at the launch of Music Television (MTV) on August 1, 1981, a live version was the channel’s 207th video played that day.

Side one closes with “Gotta Lotta Nerve (Perfect Perfect),” which transports the ’50s doo-wop sound that the pair grew up with while plugging into the then current bip-bop synthwave, complete with appropriate lyrics like “Everything you do is perfect, perfect/Everywhere you go is perfect, perfect” that veer off into the land of electronic chanting.

Side two opens with the album’s second single, a cover of the Righteous Brothers’ 1964 #1 “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’” in a mostly faithful rendition. It builds from a tender ballad the duo trading off passages that echo the original, and escalates into the climax of a hard rock plea, nicely showcasing the vocal stylings of Hall and Oates. While not mimicking the success of Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield’s version, it ended up at a respectable #12 on Billboard’s Hot 100.

The album’s fourth single, “You Make My Dreams,” began as a series of happy accidents, starting as a demo from Hall with a fairly straightforward narrative that he claimed was “too cliché.” But in a joint 2021 interview he revealed that, “There’s something very direct and positive about the lyrics, and it never stops. It’s relentless. I think maybe that’s part of its appeal to people.” That ongoing appeal—from its inclusion in the 2009 film 500 Days of Summer to a 2021 Kermit the Frog rendition on the U.S. version of the Masked Singer—keeps its effervescent fizz atop the pop culture zeitgeist.

At this juncture in the long catalog of Daryl Hall songs, it can come as a surprise that “Every Time You Go Away” is in fact his composition and was first included as Voices’ ninth track. While presented as a soulfully arranged ballad, accented by Hall’s soaring church-like delivery, the tune is now best known for the 1985 interpretation from British singer Paul Young. Young’s husky vocals, combined with an appearance at Live Aid, catapulted the song to international success, outstripping the initial interpretation, but no doubt sealing its immortality in the pop music pantheon.

Oates’ second offering, “Africa,” chugs along with a stereotypical jungle backbeat, barely saved by Hall chiming in with supplemental harmony and a middle-eight funky sax solo. Unfortunately, the lyrics suffer from a cringe-worthy ’80s borderline misogynistic viewpoint: “My baby went to Africa/I packed my bags, I gotta get to her/Before the lions and tigers try to jump on her bones,” with no other redeeming qualities left to ponder.

The album closes with “Diddy Doo Wop (I Hear the Voices),” a conclusion to a series of real-life sinister events involving Hall and Oates. In a bizarre admission, David Berkowitz, aka “Son of Sam,” claimed he was inspired to take on his murderous killing spree from the duo’s “Rich Girl.” The absurdity of this (not even allowing that he started his rampage before the song was released) was how an unbalanced individual would make a connection to musicians with disturbing results. “I can’t help it if deranged people like our music,” Oates said in a 2020 interview. “We wrote the title track for the Voices album based on the headlines in New York City at that time, because there was a guy riding around on the subway slashing people with a machete. We were looking at the stories, wondering what could make somebody so crazy that they would be driven to do something so terrible.”

“Without a doubt, Voices was a pivotal album in our career,” Oates said in a recent interview. “It really marks a moment where Daryl and I decided to take creative control over our own music. It was the first album that we produced ourselves, and the resulting success really validated our gut feeling of that. And we were right all along.”

Voices was released on July 29, 1980, and spent 100 weeks on the Billboard 200 album chart, peaking at #17. It reached platinum status (certified sales of one million) in January 1982, and “Kiss on My List” was designated gold status with sales of 500,000 in 1981. Daryl Hall and John Oates remain the most successful duo of all time and were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014. Their recordings are available in the U.S. here and in Canada here.

Watch Daryl Hall and John Oates perform “Kiss on My List” live in 2003

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI still remember hearing “Every Time You Go Away” later in the ’80s during my college years and thinking, “Dang, that sounds like it should be a Hall & Oates song.” Then I found out later there was good reason for that determination, because it WAS a Hall & Oates song, but wasn’t released as a single.