Author David Browne on His New Book on the Greenwich Village Music Scene

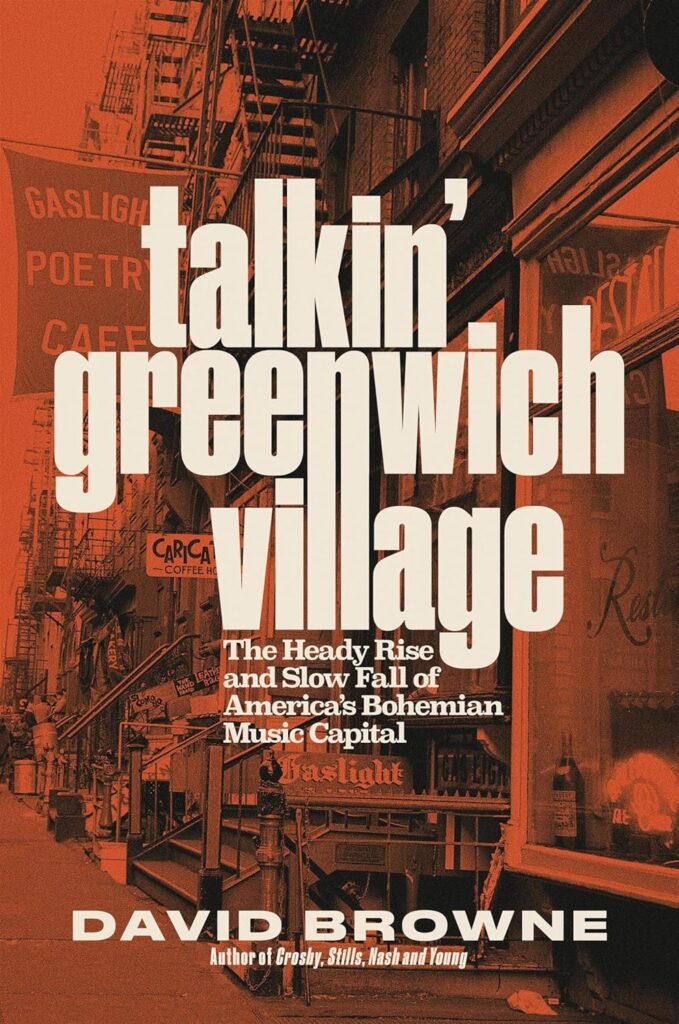

by Jeff Tamarkin In his fascinating and meticulously researched new book Talkin’ Greenwich Village, subtitled “The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital,” veteran author and music journalist David Browne chronicles the history of the New York City neighborhood that has given a home, over several decades, to countless important musicians working within myriad genres. It arrived via Hachette Books on September 17, 2024, and is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

In his fascinating and meticulously researched new book Talkin’ Greenwich Village, subtitled “The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital,” veteran author and music journalist David Browne chronicles the history of the New York City neighborhood that has given a home, over several decades, to countless important musicians working within myriad genres. It arrived via Hachette Books on September 17, 2024, and is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

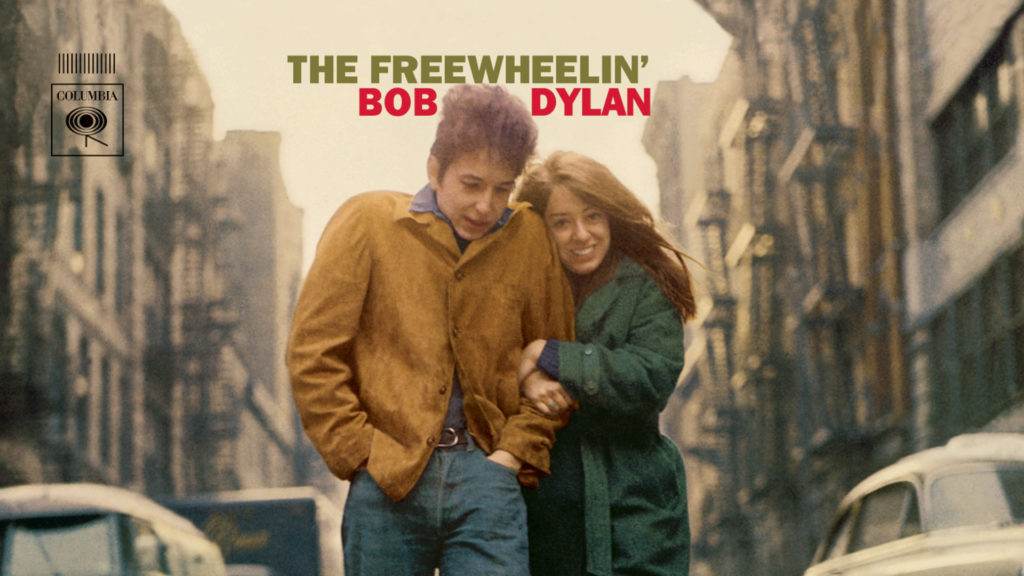

As the promotional copy of the book states, “Although Greenwich Village encompasses less than a square mile in downtown New York, rarely has such a concise area nurtured so many innovative artists and genres. Over the course of decades, Billie Holiday, the Weavers, Sonny Rollins, Dave Van Ronk, Ornette Coleman, Bob Dylan, Nina Simone, Phil Ochs, and Suzanne Vega are just a few who migrated to the Village, recognizing it as a sanctuary for visionaries, non-conformists, and those looking to reinvent themselves. Working in the Village’s smoky coffeehouses and clubs, they chronicled the tumultuous ’60s, rewrote jazz history, and took folk and rock ’n’ roll into places they hadn’t been before.”

Browne conducted more than 150 new interviews with artists whose careers flourished in the Village—from singer-songwriters like Vega, John Sebastian, Shawn Colvin, Suzzy and Terre Roche, Arlo Guthrie and Eric Andersen to jazz greats Sonny Rollins and Herbie Hancock to members of classic rock bands like the Blues Project—and took a deep dive into the history of the many venues that hosted these artists. Browne also recounts the often-tense politics that at times threatened the thriving downtown music scene and, according to the promo copy, “the racial tensions, crackdowns, and changes in New York and music that infiltrated the neighborhood.”

Browne is a senior writer at Rolling Stone and author of eight books (on subjects including Jeff Buckley, the Grateful Dead, Sonic Youth, and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young). He was previously a staff reporter at the New York Daily News and music critic at Entertainment Weekly.

Best Classic Bands spoke with Browne about Talkin’ Greenwich Village and the music scene at the heart of the book.

Best Classic Bands: Why did you want to write a book about the history of the Greenwich Village music scene, and how did you unravel such a complex, vast story with so many tributaries?

David Browne: I actually first had the idea for this book a few decades ago, when I took note of the domino effect of so many Village clubs shuttering: Folk City, the Lone Star Café, the Village Gate and on and on. This was not only after I had spent time as a reporter at the Daily News and spent quality time in those clubs and so many others in the area. It was very startling and signaled something profound. For whatever reason—other projects—I put it on the back burner, but the project returned to life thanks to two return visits in 2019. For a story on Ramblin’ Jack Elliott for Rolling Stone, we did a walking tour of the area around Bleecker and MacDougal [Streets], which reminded us both of all the long-gone venues (Jack has a great memory, too). A few months later, I once more wove my way through Village streets on the way to a Thurston Moore show at [the club] LPR, and walking past clubs that were now restaurants or banks or drug stores, it became doubly clear that the neighborhood was hardly a music neighborhood anymore and only a few of its famed venues (the Bitter End, Village Vanguard, Café Wha?, the Blue Note) survived. A 2020 RS story I wrote on the life and death of David Blue, an early Village stalwart, also inspired me to finally dive into the book. And when the pandemic lockdown hit that same year, who knew how many of the still-standing clubs would even survive? The timing just felt right.

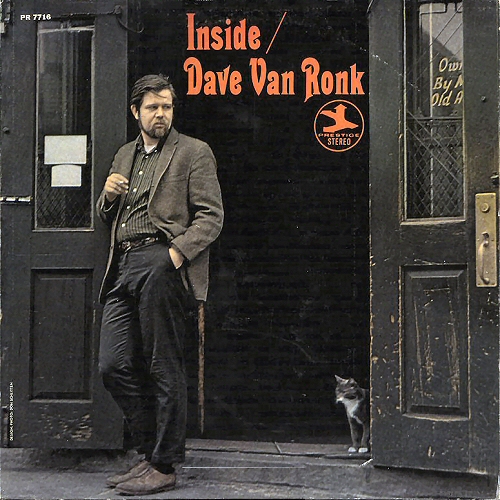

From the start, I knew the arc of the story I wanted to tell—the seeds, rise, heyday and gradual crumbling of the scene between the ’50s and the ’80s—and dove into the research, interviewing anyone who was still with us, reading or re-reading old books and articles, and starting a document, an ongoing timeline of anything and everything significant (club openings and closings, significant or forgotten shows, etc.). Pulling it together into a narrative was the biggest challenge. I was partly inspired by Isabel Wilkerson’s epic The Warmth of Other Suns and the way she followed the journey of Black Americans from the South to other parts or the country in the last century. I wondered if I could approach my book in a similar manner. I bought a pack of index cards and wrote some of those events on each and moved them around on my floor, making sure I returned to certain pivotal characters (like Dave Van Ronk or the members of the Blues Project) from time to time to ground the story in some central figures and employ them as windows into particular Village eras. That part of the work drove me crazy at times, but I’m hoping the work paid off and the narrative is easy to follow.

Why did the Village become such a magnet for musicians, and are there shared characteristics of artists who flock there?

I think part of it was its history, the way the Village had long attracted writers, artists and poets dating back to the 1800s. It was a symbolic neighborhood. I think the relative compactness of the area also played a part, especially once more coffeehouses and clubs started opening at the dawn of the ’60s. Whether you were a musician or a fan, you could literally go to, say, the Gaslight, cross the street for a gig at the Café Wha or Commons or walk around the corner and find the Bitter End or the Gate. There were a batch of nightspots in midtown, but nothing similar existed in any other part of town. As far as shared characteristics, I think what connects many of Village musicians, in whatever genre, was their devotion to integrity and a lack of compromise. Whether it was Dylan, Van Ronk, the Blues Project, the Roches, Suzanne Vega or many others, these are people who weren’t averse to having a hit record but wanted to do it on their terms and with their identities intact. I’m hoping that tradition will be passed along to the next generation of artists who gravitate there in the future.

Watch rare footage from the Gaslight Poetry Cafe from 1962, including Noel Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul & Mary

You’re a New Jersey guy but you lived in the Village starting in your college years. What was your own first-hand first impression of the music scene there, and what was happening at the time?

As a high school kid in northeast Jersey in the late ’70s, my first impression of the Village music scene were those amazing things called “used record stores”! A fellow music-head friend and I heard there were a slew of them in the Village, where you could bring in your unwanted vinyl, trade them in and buy new records! So that’s what we did. I remember discovering Second Coming Records on Sullivan Street and only getting maybe $10 for a huge pile of LPs I carted in on a NJ Transit bus. Not the bounty I expected, but I bought one or two records there; one of them, if I’m remembering correctly, was Roger McGuinn’s Peace on You.

Related: When Jimi Hendrix was a Village staple

When I moved into my freshman NYU dorm in 1978, I sensed that the mythic ’60s were over and that you weren’t going to see Phil Ochs (who had recently died) or Dylan or most of that gang anymore. But I also remember walking around the neighborhood with my new roommates the first night we moved in and passing by the Bitter End, Kenny’s Castaways and the Gate and realizing there was still a scene of sorts, and plenty of other record stores too. I went to my first show at the famed Bottom Line that fall—Dr. John with opening act Alicia Bridges of “I Love the Nightlife” fame. Even though that club was only four years old at that time, the experience felt like attending music church, and the same with a jazz brunch I caught one afternoon at the Vanguard. Every Wednesday morning I’d buy the Village Voice and check out the club ads, and I began taking notice of a new batch of singer-songwriters playing at Folk City and saw the Smithereens at the Other End Café soon after. It wasn’t the ’60s, but I felt that the scene was still vibrant and had plenty to offer.

For a lot of people of a certain age, the Village will always be associated with folk music made by troubadours with acoustic guitars—Dylan, Ochs, Eric Andersen, Richie Havens, Van Ronk, etc., and later on, people like the Roches and Steve Forbert. But you make a point of explaining that there was always a lot more than that going on, especially a whole jazz scene centering in venues like the Village Vanguard. Why do you think the Village appealed to such a variety of artists?

This is one of the aspects of the Village’s music legacy that also separates itself from those in many other cities—its eclecticism. I was reminded of this as I paged through week after week of Voice club ads starting in the late ’50s. I could cite dozens of examples, but one weekend in 1965, you could have seen Phil Ochs and Eric Andersen at the Gaslight, Ornette Coleman at the Vanguard, Coleman Hawkins at the Five Spot, and Dick Gregory and Arthur Prysock at the Village Gate. The fact that the Village was somewhat off the beaten path, a world unto itself, also helped foster all these artists in different genres: It felt like a place where you could go not just to reinvent yourself (sometimes with a new name!) but also ply your trade and try out a new story-song or a free-jazz romp to a small, discerning crowd. Once the music business began turning its gaze to the Village and sending A&R people down there, well, that didn’t hurt either in terms of the area’s allure.

Watch Richie Havens perform “Handsome Johnny” at the Bitter End in 1967

There was also a vibrant rock scene there starting in the ’60s—bands like the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Blues Project, the Fugs, etc. How did that come about and was it separate from the folkie thing or was it all pretty much one big happy family?

The electrification of the Village was one of the most fascinating parts of the story to me. Everyone thinks it all started with Dylan at Newport in the summer of ’65, but in fact, Village folkies had already started plugging in months before that, a list that includes Tim Hardin, Jesse Colin Young, John Sebastian and the Spoonful, and the late, great Danny Kalb and what became the Blues Project. Even proud acoustic picker Happy Traum, with whom I was privileged to spend hours before he passed away this summer, briefly had a rock band. Dylan was cutting the half-electric Bringing It All Back Home in early ’65, but he wasn’t alone in exploring the new possibilities.

Watch the Blues Project perform “Steve’s Song” in 1967

Part of the motivation was success and the impact of A Hard Day’s Night in ’64. And you can’t blame anyone back then for wanting to branch out and maybe play to more than people than 50 at the Night Owl or some basement club. And look at all the great art that came from Village musicians plugging in: all those enduring records by the Spoonful, the Youngbloods and the Blues Project among them.

One of the reasons I focused on the Blues Project—aside from their wonderful music, especially the Projections album—is the way the band embodied the tensions that sprang from that literally charged period. The gifted [Blues Project keyboardist/vocalist] Al Kooper aside, the other members were grounded in folk, blues or jazz; several of them even took guitar lessons with Van Ronk. But the friction between Kooper, who yearned for the band to have a pop hit, and Kalb, who preferred they stick with classic blues and honor the masters, came to embody the clash between purity and commercialism that ricocheted through the Village at the time. Could you have a hit record while staying true to yourself? Were all those tourists and out-of-towners suddenly invading the neighborhood good or bad?

Listen to a rare live recording of the Lovin’ Spoonful at the Night Owl Cafe

Is there one individual artist you consider the King or Queen of Greenwich Village music, someone that is intrinsically associated with that scene? An unsung hero of the Village, perhaps? And why that person?

I always knew I had to include Dave Van Ronk, but the more I researched his life and impact, it became clear that he really did live up to his unofficial title as the Mayor of MacDougal Street. Van Ronk may not be totally unsung, but some people may not fully realize what an impact he made and the breadth of his legacy. His story was interwoven with the scene itself. He moved to the Village in the mid ’50s and, unlike many who came after, like Dylan, never left; he still lived there when he died in 2002. He was there when the coffeehouses started popping up, he was there when those places were harassed by cops or the Mob or the neighborhood, he was there when Dylan arrived, he was there when everyone plugged in (and started his own short-lived rock band too), he was there when it petered out in the early ’70s, and he was there when a new generation of troubadours brought it back to life in the late ’70s (he was involved with the Speak Easy club that fostered Vega, Shawn Colvin and others). He was also a guitar teacher or mentor to Danny Kalb, Maggie and Terre Roche, Christine Lavin and many more. And his records, while not exactly commercial due to his bark of a voice, are largely wonderful and encompass folk, jazz, blues and rock, the range of Village music itself. As a result, his life and work is threaded through the narrative.

Watch Dave Van Ronk perform “Green, Green Rocky Road” live

You conducted over 150 new interviews for the book. What were some of the new things that you discovered about the Village music scene, and do you have a favorite interview out of all those? Also, who, among those that have died (or didn’t grant interviews), would you most like to have spoken with?

Thanks to New York City archives, I learned more about the infamous [1961] “beatnik riot” in Washington Square Park and the ways in which the city was intent, in one way or another, on squashing hootenannies in that park. I gained more insight into the city’s cabaret laws and how they hampered the Village scene (no drums!), as well as more about the tensions between the Italian-Americans in the area and all those kids and venues who invaded their neighborhood. I learned more about the infamous movie whose success paved the way for the Speak Easy and more about the challenges the Roches faced when they ventured outside of the Village. (Booed by Boz Scaggs fans? Who knew?) I learned about the connection between the closing of Folk City and Robert De Niro’s mother and the very personal back story behind Vega’s “Luka.”

Watch Suzanne Vega sing “Luka” on the David Letterman show

Of those who passed, I was sorry to not be able to interview Len Chandler, the Ohio-born Black singer and guitarist who was an integral part of the Gaslight scene and had first-hand encounters with racism in the Village. We spoke a bit when I started, but he was having health issues and passed away while I was in the midst of the book. I also would have loved to have spoken with Joe Marra, who started the Night Owl, and Alix Dobkin, one of the first Village musicians to come out. Both passed away during my research, along with Patrick Sky, Ian Tyson (whom I had already interviewed a few times in my career) and others. Fortunately, I was able to spend time with both Danny Kalb and Happy Traum before they passed, and I valued my time with both of them.

Greenwich Village has always been about change but there are some things that never change. There is still a very active live music scene there. What is most similar about today’s Village and the classic era and what has changed the most?

What’s clearly changed is the way in which most of the spaces that housed the clubs are now drugstores, banks or swanky restaurants. But every so often when I was there on a weekend afternoon or evening, a reminder of what it had once been, and could be again, resurfaced. One afternoon this past winter, I popped into an afternoon jam session at Smalls, a jazz club that opened in the ’90s and is, in the grand Village tradition, in a basement. Sitting there listening to young players swap solos gave me hope that the music aspect of the Village could come to life once more, someday.

Watch: Take a stroll through the streets of Greenwich Village in 1960

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationMr. Browne’s “talkin’ greenwich village” is a wonderfully definitive history of the cultural mecca that spans decades. It does not focus on any one individual although Dave Van Ronk and a young Bob Dylan figure prominently in the story. Insightful and engaging, I consider it a must-read for music devotees of all eras.