What is the Greatest Record Ever Made? A New Book Offers 145 Answers

by Jeff Tamarkin What is the greatest record ever made? Is that a question that can ever be answered definitively?

What is the greatest record ever made? Is that a question that can ever be answered definitively?

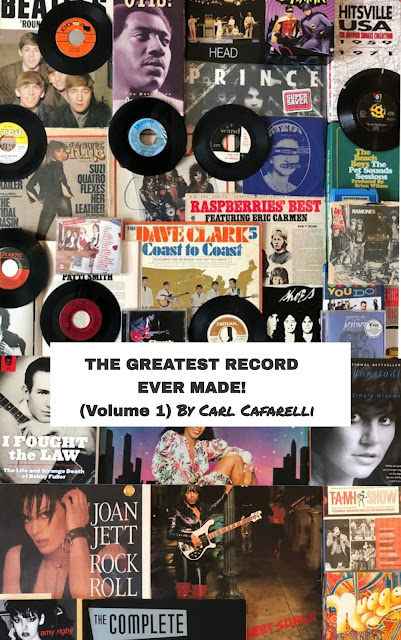

Writer and DJ Carl Cafarelli has some thoughts on that subject, and he offers them for consideration in The Greatest Record Ever Made (Volume 1), his new book, published in July 2024 and available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

“Our favorite records don’t live in isolation. Each one has a story,” says Cafarelli in promotional materials for the book. “Insisting that an infinite number of tracks can each be the greatest record ever made (as long as they take turns), [the book] ties together threads connecting classic rock, soul, pop, punk, hip-hop, and bubblegum across decades of hits, misses, critics’ darlings, one-hit wonders, Rock and Roll Hall of Famers and complete unknowns. The result reads like an irresistible mixtape in book form, compelling the reader to follow its flow from song to song and chapter to chapter as if it were a novel.

“As an experienced pop historian and journalist, Cafarelli knows the importance of recording facts and figures accurately,” the announcement continues. “But passion is of equal importance. We don’t crank the volume for fave rave sounds as academics; we listen as fans, as people living this complicated life with music as not merely its soundtrack, but as its heartbeat. Records reflect our hopes, our disappointments, our successes, our mourning, our love, our bitterness, our fear, and our will to dance in spite of it all.

“Why did the Monkees go from the top of the pops in 1967 to seeming has-been status in 1968? How did James Brown respond to the British Invasion? What minefields of racism, sexism, homophobia, ambition, frustration, depression or loss were navigated by Little Richard, Dusty Springfield, the Go-Go’s, Elvis, Sly and the Family Stone, the Kinks, the Beach Boys, the Supremes, and Material Issue’s Jim Ellison? Were the Ramones as much a bubblegum band as they were a punk band? When does a group succeed or fail in its quixotic quest to be the next Beatles?

“And why does listening to pop music sometimes make us want to cry?”

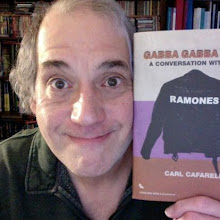

Cafarelli is the author of Gabba Gabba Hey! A Conversation with The Ramones (Rare Bird Books, 2023). He has written for Goldmine, DISCoveries, The Syracuse New Times and other publications and, since 1998, has been the co-host (with Dana Bonn) of the internationally renowned weekly broadcast and internet radio show This Is Rock ‘n’ Roll Radio with Dana & Carl. He is the author of the daily blog “Boppin’ (Like The Hip Folks Do).”

Best Classic Bands sat down with Cafarelli in an attempt to find out exactly what is the greatest record ever made.

Best Classic Bands: Why did you want to write this book and what was the genesis of it?

Carl Cafarelli: I’ve always been obsessed with pop music. I was four years old when Beatlemania invaded the States, but even little kids were at least a little bit aware of the Beatles in ’64. Watching them on The Ed Sullivan Show and seeing A Hard Day’s Night at the drive-in solidified that feeling that the Beatles were synonymous with popular music, at least as I saw it. I recall watching a Popeye cartoon on TV, and when a scene depicted a radio being smashed open, I was surprised the Beatles didn’t emerge from the debris. Weren’t radios where the Beatles lived?

But my obsession didn’t begin with the British Invasion. I remember being three years old, pestering my Aunt Anna to play 45s. I remember Sam Cooke and the Four Seasons, Eydie Gorme, Gene Pitney, the Beach Boys, Freddy Cannon, all before ’64. I remember Chubby Checker, though presumably as an oldie; it seems a stretch to think I knew “The Twist” at the time of its chart domination in 1960, the year I was born. I don’t think I was that precocious. Throw in my mother’s Broadway LPs, and there was always much music to indulge the obsession.

Fast-forward through decades. I wanted to be a writer, and I somehow fell into writing about rock ‘n’ roll. I freelanced for 20-something years, grew tired of it, and by 2006 or so I’d all but given up on pop journalism. Ten years later, the death of David Bowie hit me with greater force than I would have thought likely. I started a daily blog, Boppin’ (Like The Hip Folks Do), and the vast majority of my blog posts are music-related.

Given all that, writing this book was inevitable. My goals and interests as (I guess) a music pundit have changed; I no longer write reviews or histories, neither of which appeal to me as a writer anymore. I can’t play or sing, but my music obsession is as steadfast as ever. I want to write essays that connect with the way the music makes me feel.

The concept of “The Greatest Record Ever Made!” started on This Is Rock ‘n’ Roll Radio, the weekly show I co-host with Dana Bonn. Enthusiasm is its own reward. Why not be unashamedly enthusiastic about the music we love? For a long time, Dana and I defaulted to Big Star’s “September Gurls” as our choice for the best-ever individual track. Then we started to think maybe it was “Do Anything You Wanna Do” by Eddie and the Hot Rods. Then our minds wandered. And we figured, what the hell, an infinite number of tracks can each be the greatest record ever made, as long as they take turns. If you’re a fan of pop music, any record you love occupies the entirety of your world when it plays. Each Fave Rave record is the greatest in its own infinite turn.

I felt compelled to turn that notion into a book.

What were your criteria in determining which records were worthy of inclusion in the book?

Feel. Plain and simple. I approached the book like I would approach constructing a mixtape, with specific sequencing meant to flow with deliberate intent. I started with a list of potential tracks to exalt, and I fine-tuned the list for years. I wrote my first GREM! entry in 2016, and I announced my intent to write the book in 2018. Its contents changed many, many times.

The most important considerations for me involved what songs seemed to fit as an overall narrative, as a book one could read from start to finish and sense a connection from chapter to chapter, track to track. That was, frankly, a much more relevant concern to me than whether or not one of my all-time favorites—say, “It’s My Life” by the Animals, or “Heart Full of Soul” by the Yardbirds—was left out of the book in favor of some other record that I don’t love as much, but which suited the needs of the overall picture I was trying to render.

I’m not sure how deep I got into the process before I realized that this book is my life story disguised as a collection of 145 essays about 145 records. Pop fans live inside the grooves of the music they play. I’m no exception to that, and I don’t want to be an exception to that. We remember the record that accompanied a first love, a first heartbreak, the loss of a friend or family member. In the book, I also use these records to discuss—or attempt to discuss—issues well above my pay grade, from racism and sexism and homophobia to depression and suicide, religion to politics, love, mortality. Batman. And radio. I love talking about the promise of radio.

The book was never intended to be an attempt to concoct an inclusive list of the best songs ever. Click bait, and I could not be less interested. The Volume 1 in the title is a specific nod to the fact that there are hundreds of other songs on roughly equal footing with the 145 I selected here. And that will remain true regardless of whether or not there is ever a Volume 2.

And the fact that it’s 145 songs—not 150, not 100, but 145—is deliberate: One 45. That’s what it’s all about. One 45 at a time, or maybe one virtual 45 at a time, regardless of format.

Very clever, that one 45 thing. You do focus on individual songs rather than albums. Why?

I am a child of Top 40 AM radio, so I have always been more of a single-song guy. I have favorite albums—Pet Sounds; Village Green Preservation Society; Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones, Ltd..;the first four Ramones records; Tell America by an obscure group called Fools Face; everything the Beatles did before Sgt. Pepper…and then still also Pepper, the White Album, Abbey Road, etc.—but I’m generally more moved by the compact appeal of individual songs, and intrinsically more thrilled by the way individual songs by different artists sound together. Again, it’s the mixtape approach, and the approach Dana and I use to program a weekly radio show. Whoever called 45s the building blocks of rock ‘n’ roll, man, I agree.

Everyone has their own favorite records. Going into this book, how did you differentiate between “Records that Carl likes” and “Records that are great whether Carl likes them or not?” Or are they one and the same?

For rhetorical purposes, they’re the same. I’ve never seen any reason why one should remain objective about pop music. What fun is that? We need objectivity in reporting facts and figures accurately, sure, and we must always be wary of attempts to rewrite history. The Monkees did not turn down a chance to record “Sugar Sugar,” a song that didn’t even exist in 1967, when urban legend claims it was offered to them. “My Ding-A-Ling” was Chuck Berry’s only # 1 hit, a fact that I would like to rewrite, if only I could.

But playing records? Listening to records? If there are gods above, they gave us an inalienable right to dig what we dig, and to be proud of what we dig.

With that said, I made an effort to reach for some…universality? But I tell ya, a wise man who used to be my editor at Goldmine once told his freelancers that anyone with half a brain knows this is all opinion anyway; just record the facts accurately, and try to tell the story in an interesting way. That advice has always served me well.

There have been literally millions of records made over more than a century now, in hundreds of genres. How did you even begin to narrow that down, and when did you know you were finished?

“Finished…?!” As if. IT SAYS VOLUME 1 RIGHT IN THE TITLE!

There are records that have sold millions of copies and records that only a handful of people have heard. Where does a record’s popularity figure into its greatness? In other words, “You’re Having My Baby” and “Disco Duck” sold millions of copies while some of the records you include in the book, by artists like the Bandwagon and the Cocktail Slippers, are pretty obscure. By definition, wouldn’t the first two be greater than the second two because more people bought them?

Heh. 500,000,000 Rick Dees fans can’t be wrong!

We can’t love what we’ve never heard. Well, maybe one would love never having heard “You’re Having My Baby,” but that’s beside the point. Popularity brings music to our ears. Some of it we might like. Some of it, well, not so much. A lot of people develop self-doubt about secretly loving pop hits that their hip peers disdain. That’s nonsense. There are no guilty pleasures in pop music. Again, and always: Dig. What. You. Dig.

Popularity can be a factor in determining a potential Greatest Record Ever Made, but it’s at least as likely to be a negative factor rather than a positive factor. Overall, a song’s popularity is probably nearly irrelevant. It only matters if an individual thinks it matters. And if YOU like it, to hell with anyone—even me!—who says you shouldn’t.

On the other hand, a track’s relative obscurity should never be a negative. There are so many great songs out there that I haven’t heard yet! They weren’t popular enough to reach my ears, at least not yet. But I insist any proudly obsessive pop zealot can rattle off dozens of examples of great individual tracks—the GREATEST individual tracks—that no one else seems to know about. It’s our collective mission to rectify that. Here on Earth, God’s A&R work must truly be our own.

Listen to “Disco Duck…” Just kidding, you don’t really have to.

I view all of this as nothing more than friends turning other friends on to fresh discoveries in music, whether new or old. Like, y’know, Hey, you’ve gotta hear THIS! Missionary work. A friend of mine, Dave Murray, introduced me to “Life Goes On,” an incredible but obscure 1965 soul single by Verdelle Smith. I loved it, and I wound up writing a Verdelle Smith essay for the book. That, as they say, is what friends are for.

And writers should follow their instincts. When I first heard the Bandwagon’s “Breakin’ Down the Walls of Heartache,” I didn’t want to listen to anything else for a day or two—just the Bandwagon, over and over. When I listen to the Cocktail Slippers’ “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre” or Holly Golightly’s cover of the Ray Davies song “Time Will Tell,” it’s not for a mere once in a row. And when I first heard “Please Don’t Touch” by Headgirl—the combined forces of UK metal acts Motörhead and Girlschool covering Johnny Kidd and the Pirates—I wasn’t interested in listening to anything else over the course of that weekend; just “Please Don’t Touch,” on repeat. Delighted obsession. That’s the nature of a potential Greatest Record Ever Made.

How did you deal with your own listening preferences? For example, some genres are pretty much absent from the book, while others are represented in abundance. Is that, to borrow a phrase, fair and balanced?

I believe in Irwin Shaw’s description of a writer’s ongoing goal: To report “this is where I think I am and this is what this place looks like today.” I don’t think it has to be a different goal for folks writing about music. We can share how things look (and how they sound) from our perspective, and hope our report translates into something an audience deems relevant.

I don’t listen to jazz, I don’t listen to classical, I don’t listen to hip-hop, I don’t listen to modern country and I don’t listen to current pop music. I try to be upfront about all of that, so people can determine whether or not whatever I may have to say about Dave Brubeck or Merle Haggard or Melle Mel is within their own bandwidth, and may (or may not) be worth their while to check out. I won’t even attempt to tackle classical.

But excuse my hubris here: My jazz chapter (“Take Five”) is, I think, a very good confessional essay about not understanding jazz, but acknowledging that it’s my loss, not jazz’s loss. My country chapter (“Mama Tried”) is an emotional reflection of loss and responsibility playing within my single degree of separation from rural roots. My rap chapter (“White Lines [Don’t Don’t Do It]”) is an unexpected embrace of a track I loved when I heard it on college radio in the ’80s, my ultimate dearth of interest in hip-hop notwithstanding. My POV is rock, pop, soul, bubblegum, R&B, punk and things that go jangle in the night; there is so much that is at least peripheral to that point of view, and I’ve tried to include some of it within my broader scope.

I hated the Grateful Dead; my chapter about coming to terms with the dichotomy of hating the Dead and loving “Uncle John’s Band” (and eventually realizing, y’know, ain’t no time to hate, barely time to wait) interweaves with the difficulty of watching my daughter grow up and move out, and the contemporaneous trouble of my mother’s path toward slipping away from this world. I address a few acts I never cared for—Eagles, Pink Floyd, Bob Seger—and discover unexpected common ground, to the extent there is common ground. I do the same with three chapters about disco.

And I pound the console on behalf of the Ramones, the Monkees, the Flashcubes, power pop and more. If we’re talking about pop music, it makes sense to extoll the virtues of what we like. We get back to Irwin Shaw. Where I think I am. What this place looks like today.

On a related note, in some cases you chose a more obscure record by an artist rather than their hits. Case in point: the Cowsills. Instead of “Hair” or “The Rain, the Park and Other Things,” you went with a later track, “She Said to Me.” I personally would have chosen “The Rain…” and have never heard of “She Said to Me.” Prove me wrong.

I respectfully recommend you pause this interview and check out the Cowsills’ 1998 album Global, my favorite album of the ’90s, and the home of the fabulous track “She Said To Me.”. Maybe you’ll dig it, maybe you’ll be indifferent to it. But getting back to what I said above about friends recommending music to friends: Hey, you’ve gotta hear this.

OK, we did, and it’s pretty great. Here it is for those others who’ve never heard it.

Addressing a well-known act’s grooves less traveled can be its own best reward. It’s not hipsterism; I despise hipsterism. It’s just a deeper dive, best realized without snark or derision. I love the Cowsills’ earlier work, especially “Hair” and “Love American Style.” The Global stuff enhances my affection for what came before. Like I say about the Monkees’ box office dud Head: It’s the grit that gives the cotton candy substance.

I’m not an iconoclast; that would bore me. My book is filled with obvious choices, by Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, the Kingsmen, King Elvis I, Lesley Gore, the 5th Dimension, Wilson Pickett, Dylan, the Ronettes, Marvin Gaye, the Easybeats, Ben E. King, the Drifters, Del Shannon, Sam and Dave, the Four Tops, Dusty Springfield, Lulu, the Drifters, et al. I picked them because the obvious choice seemed the right choice.

Once you narrowed down your choices, how did you approach the writing? What did you want to get across about each record?

Most of the chapters—and I wrote way more than I could fit into a single book—were written independently, and then I set about the task of assembling the parts into a greater whole. As I said above, more than any other single consideration, I wanted the book to flow from song to song, chapter to chapter. And that flow had more to do with narrative than with the music (though I can attest that this specific sequence of tracks just slays as a mixtape/playlist). It was important that this book read as a book, not a collection of unconnected essays. Maybe that’s illusory, like the notion of the individual tracks on Sgt. Pepper forming a greater whole, a concept, even though they are still just individual tracks.

This book is the partial soundtrack of my life, and—as we all know—the best soundtracks are not incidental; they are as much a part of the action as anything else. I wanted to convey that feeling, that sense of context. I think—and hope—the stories are sufficiently relatable to transcend just being about me. When all is said and done, The Greatest Record Ever Made! (Volume 1) is not a history book or a reference book; it’s a love letter to pop music, told by someone whose life has revolved around that love.

Related: The best music books of 2023

I’m not sure when your cutoff date was, but it’s fair to say most of your picks predate the 21st century. Is anyone making great records today that could compare to those in your book?

The most recent track in the book is Eytan Mirsky’s “This Year’s Gonna Be Our Year,” and that’s from 2012, 12 years old. There are a handful of other 21st century songs represented (Marykate O’Neil’s “I’m Ready For My Luck to Turn Around,” the Cocktail Slippers’ “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre,” Amy Rigby’s “Dancing With Joey Ramone,” the New Pornographers’ “All for Swinging You Around,” the Jayhawks’ “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me,” Tegan and Sara’s “Walking With a Ghost,” Holly Golightly’s “Time Will Tell”), but yes, I am clearly still infatuated with stuff from before Y2K.

There is a ton of wonderful new stuff, always, just as there are mile-high stacks of compelling older material awaiting my notice and subsequent thralldom. Any record you ain’t heard is a new record. I constantly hear new releases that grab me. Given my interests, most/all such gems fall under the radar of popular culture, so they tend to be obscure. Listing current acts I like would come across as an exercise in the hipsterism I so abhor, but trust me: There is always great new music being created. Sometimes you have to dig for it, but it’s out there. I co-host a radio show specifically dedicated to mixing such fresh revelations with classic fave raves. I have a lot of music-fan peers doing their own versions of the same ongoing missionary worth.

It’s a divine calling! Plus it’s fun.

What do you say to someone who argues, “How could you leave out…? Are you crazy?!”

Write your own book. NO! I KID! I’m a kidder.

So, Carl, what is the greatest record ever made, and why? And how many volumes would it take before you got around to every “Greatest Record Ever Made”?

By design: an infinite number. The journey is the story, and there is always another record to play. And another. And another. And…you know. A Volume 2 seems a lot more likely now than it did when I started putting this together a few years back. I have chapters written about R. Dean Taylor, Wham!, the Rubinoos, the Five Stairsteps, the Velvelettes, the Everly Brothers, Gene Pitney, the New York Dolls, the Mynah Birds (Rick James and Neil Young recording for Motown in 1966!), Sam Cooke, Love, the Searchers, Alice Cooper, the Dixie Cups and more, and incomplete bits about Peggy Lee, Ray Charles, the Pretenders and a cast of dozens. WDHA-FM DJ Jim Monaghan suggested I write about the Rolling Stones’ “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” and that’s a damned good idea that never even occurred to me.

No matter how many volumes I do, this story, this conversation, continues. And each of the tracks is on equal footing with all of the others. An infinite number, as long as they take turns.

(But it’s Badfinger. “Baby Blue.” At least for today.)

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationMy fave years for singles are 1963-1969 and I would have a difficult time writing The Greatest Record Ever Made for any of those years let alone one of Cafarelli’s book’s scope.

I look forward to reading it and arguing endlessly with the author in my head …

“Penny Lane” with “Strawberry Fields Forever”. Two perfect songs– you can’t change a single note on either to improve them– on one piece of vinyl. It doesn’t get any better than that.

What a great song from the Cowsills, I think I need that book. Excellent choice with Badfinger