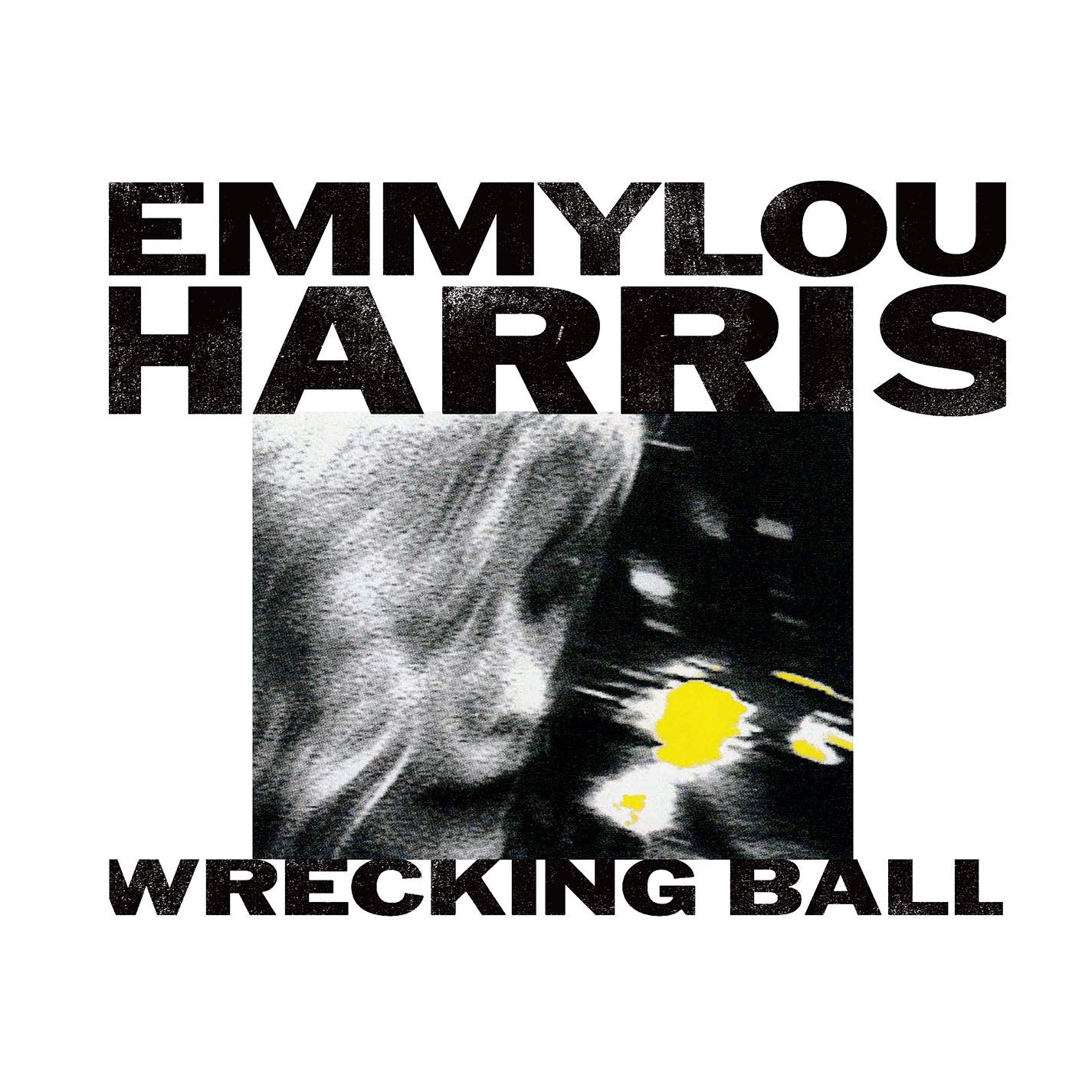

More than two decades after her arrival as a country-rock pathfinder, Emmylou Harris defied conventional wisdom by rebooting her music from the ground up. With 1995’s Wrecking Ball, she accomplished what singer-songwriter Gillian Welch later termed “that rarest and most magical of artistic feats—the reinvention of the self, true to form yet entirely new.”

More than two decades after her arrival as a country-rock pathfinder, Emmylou Harris defied conventional wisdom by rebooting her music from the ground up. With 1995’s Wrecking Ball, she accomplished what singer-songwriter Gillian Welch later termed “that rarest and most magical of artistic feats—the reinvention of the self, true to form yet entirely new.”

Two years earlier, Harris saw her career becalmed as she released Cowgirl’s Prayer under a new contract with Asylum Records. The album showed no lapses in taste or craftsmanship, drawing from a reliably strong corral of musicians and songwriters. Critics applauded the new record, but Nashville’s commercial gatekeepers were less welcoming.

Thirty years later she would recall her crucial next move: “I knew that I was no longer invited to the party at country radio, so why not try something? It was a huge turning point, because it was a sea of change that inspired me in a lot of ways that I still feel I’m carrying on from it [today].” That pivot turned away from the style developed in the wake of her transformative collaboration with Gram Parsons, largely discarding traditional country elements to start anew on a largely blank page.

To do so, Harris broke with her previous producers’ Nashville pedigree in favor of a disruptor, Daniel Lanois, the Canadian musician and producer who had graduated from engineering on Brian Eno’s pioneering ’70s ambient projects to co-producing three of U2’s pivotal ’80s albums. Lanois’ reputation as a sonic expressionist was heightened by albums with Peter Gabriel, Robbie Robertson, the Neville Brothers and Bob Dylan, for whom 1989’s Oh Mercy proved a critical and commercial rebound.

Asylum may have been reassured by Lanois’ platinum résumé, but Harris was drawn more by his solo music, which rewired folk influences with ambient electronics to haunting effect. Acadie, his 1989 debut album, referenced the historic connection between the New France colony of Acadia and Louisiana, where its exiles sought refuge after their defeat by the British in the mid-1700s. For Quebec-born Lanois that legacy inspired a bilingual song cycle bridging French folk traditions with the Gulf Coast’s Cajun culture. The songs evoked a rustic past in neo-folk ballads shaped by Lanois, Eno, members of U2 and the Nevilles contributing to stripped-down arrangements that conjured an imagined past.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Harris’ 1981 release, Evangeline

That vision exerted a powerful influence over Wrecking Ball, recorded principally in New Orleans at Kingsway, the studio Lanois established in the French Quarter in 1991. Her previous producers, including ex-husbands Brian Ahern and Paul Kennerly, preserved a synthesis of folk, country and pop evolved from Emmylou’s partnership with Parsons. In teaming with Lanois, Harris embarked upon her most artistically consequential stylistic change since that fateful collaboration. It was a gamble both forward-looking but also connected to Harris’ early career as a folk singer whose first musical hero was Pete Seeger.

Harris’ prior records retained a naturalistic approach and a familiar palette of guitars, keyboards, fiddle, pedal steel and other Music Row earmarks. At Kingsway, that more documentary strategy was shelved in favor of Lanois’ laboratory approach, building songs through extensive overdubbing and outboard electronics engineered by Mark Howard.

As he had on Acadie, Lanois multitasked, juggling electric and acoustic guitars, mandolin, dulcimer, bass, bass pedals and percussion. Joining him was fellow Canadian Malcolm Burn on keyboards, guitars, bass and percussion. U2’s Larry Mullen Jr. drummed on nine of the finished album’s dozen tracks, with percussionist Tony Hall and bassist Daryl Johnson completing the core band, with Harris on acoustic guitar.

A quantum shift in Harris’ sonic persona is immediately audible within the space of the first verse of “Where Will I Be,” a Lanois original. The opening bars cast a lonely path for the singer between the syncopated martial clatter of Brian Blade’s drums and Lanois’ liquid electric mandolin figures, with Harris trading her typically pristine intonation for a hoarser, feverish reading of lyrics painting a bleak landscape where “the streets are cracked, glass everywhere.” Lanois and Burn gradually overdub ghostly flurries of guitar and mandolin, percussion and a prominent bass line as Blade adds strategic cymbal crashes to his stalking snare and tom.

Thematically, the song weaves spiritual yearning with erotic memories as addresses addiction, faith and death itself. “Where will I be, when my trumpet sounds,” Harris sings, with Lanois adding vocal harmony against a haunted soundscape far from any honky-tonk.

From the anxiety that propels that stark opener, Harris retreats to a wistful memory of lost love in Steve Earle’s “Goodbye.” Romantic regret wasn’t new to her repertoire, but Earle’s melancholy epitaph is a raw confession confronting pain caused, promises forgotten and personal demons with the devastating admission, “I can’t remember if we said goodbye.” The hushed arrangement moves at a dirge’s pace, with Earle himself guessing on acoustic guitar, one of three tracks on which he appears.

The album sustains a mood of somber reflection throughout, continuing with “All My Tears,” written by Julie Miller, a dark hymn that finds solace in faith even as its minor-keyed melody and wordless backing vocals project a mournful beauty in the face of mortality.

Neil Young’s title track provides an apt metaphor for the project’s game-changing mission as well as one of its gentlest performances. Young’s own defiant career, famously guided by a penchant for restless experimentation, offered a precedent for Harris’ hard left turn with the album, but here his wistful lyrics offer solace and connection.

My life’s an open book

You read it on the radio

We got nowhere to hide

We got nowhere to go

But if you still decide

You want to take a ride

Meet me at the wrecking ball

…and we’ll go dancing tonight

Bell-like piano notes, spare percussion and Young’s pitch-perfect falsetto harmonies suggest a dreamscape in which the singer regards a potential lover, equal parts caution and anticipation.

Watch Harris perform the title track on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno

On paper, Wrecking Ball relies on a toolkit that would easily serve Harris’ previous country sessions: guitars, keyboards and drums with pedal steel, mandolin and dulcimer. The arrangements and ambient presentation instead push the overall sonic character away from the traditional country elements Harris had absorbed to move toward a new species of folk-rock that shimmers and hums, balancing electric and acoustic instruments with ambient details. In its leaner design, the record harkens back to her early career serenading folk club audiences, informed by the ’60s halcyon days of Joan Baez, Judy Collins and Joni Mitchell while embracing the modern edge in Lanois’ production.

The folk tradition itself infuses “Goin’ Back to Harlan,” a haunted meta-ballad explicitly grounded in traditional English ballads in its imagery and structure. Written by Anna McGarrigle (who appears elsewhere on the album with sister Kate on the album’s closing track), the song ponders age and innocence, its opening verse conjuring childhood memories “assuming roles from nursery rhymes” that give way to tragic life lessons embodied in centuries old ballads:

Frail my heart apart

And play me a little “Shady Grove”

Ring The Bells of Rhymney

’Til they ring inside my head forever…

Against the deliberate gallop of Harris’ acoustic guitar, she namechecks Willie Moore, Barbara Allen and Fair Ellen, tragic hero and heroines of yore. The song typifies her more impassioned vocal attack—age and experience added new, rawer textures abetted by a more vivid use of dynamics from clarion soprano to whispered falsetto.

On “Deeper Well,” the depth of Emmylou Harris’ commitment to her producer’s vision extends to songwriting. “Deeper Well,” written with Lanois and David Olney, works a vein of spiritual reckoning both the singer and her producer had explored in earlier work; as such, it’s also a natural companion to “Where Will I Be,” directly echoing the previous track’s metaphors for addiction. Structured as a gospel confessional, the song draws dark energy from Lanois’ dense ambient electric guitar.

The spiritual throughline emerging from the album is only strengthened with Harris’ first Bob Dylan cover. First heard on 1981’s Shot of Love and received as another example of his late ’70s focus after identifying as a Christian, “Every Grain of Sand” builds upon a title metaphor from William Blake to explore themes of sin and redemption that he had plumbed long before his declaration of Christian faith and has revisited time and again since retreating from such formal denominations. Harris’ reading is direct and heartfelt, serving the material on hand as she ties it to Wrecking Ball’s sympathetic agenda.

Lucinda Williams had already captured Harris’ attention to yield a rich, nostalgic reading of “Crescent City” on Cowgirl’s Prayer, so a Williams cover offered here isn’t surprising, although its subtext is darker. “Sweet Old World” is a tender reproof to a friend lost to suicide that leavens its melancholy with delicate images of things worth living for.

The molten electric guitar textures that simmered at the edge of “Deeper Well” reappear in the album’s least expected cover choice, a powerful take on Jimi Hendrix’s “May This Be Love” from Are You Experienced, his 1967 debut LP. Here, the track aligns with Wrecking Ball’s earthly elements while confirming Hendrix’s clear influence on Lanois as an electric guitarist who leans into raw texture and strong melodic lines in his solos.

Any reservations about his guitar chops would be further quelled during live performances on the tour that reached U.S. venues a week after the album’s September 26, 1995, release, with Harris fronting a potent live band that was a striking contrast with her larger Hot Band lineups—a taut quartet with Lanois and a killer New Orleans rhythm section of drummer Brady Blade (Brian’s brother) and bassist Daryl Johnson.

The folk minimalism of “Orphan Girl” marked an auspicious introduction to Gillian Welch, whose own version would appear on her debut album the following spring. An austere ballad, the song marries its plainspoken lyrics to a rustic gospel structure that could have been written in an Appalachian holler, framed here by dulcimer, mandolin and acoustic guitars gently propelled by hand drums. Welch and partner David Rawlings would soon emerge as avatars for ’90s alt-country at its purist neotraditional frontier.

That Lanois cast a long shadow not only over the sound of Wrecking Ball but also its thematic substance is borne out by a third Lanois track, “Blackhawk,” with images of fading passions and lives ground down by life and the “stinking air” of an industrial town. A fourth Lanois song culled from Acadie, “Still Water,” was also recorded but ultimately shelved before finally seeing release with the expanded Deluxe Version of Wrecking Ball in 2014.

With the album’s closing song, Harris comes full circle to the very beginning of her post-Parsons journey with “Waltz Across Texas Tonight,” which she co-wrote with Rodney Crowell. She had opened her major label debut, Pieces of the Sky, with Crowell’s “Bluebird Wine,” then recruited him on rhythm guitar for her Hot Band as she continued covering his songs. She would reunite with Crowell after Wrecking Ball on a pair of strong duet albums, Old Yellow Moon (2013) and Traveling Kind (2015), that showed their musical chemistry had only deepened.

Watch Willie Nelson, Daniel Lanois and Harris perform “The Maker”

After the electrifying Wrecking Ball tour, Lanois would move on to new projects, but Emmylou Harris would carry its leaner, more atmospheric format forward, her new direction further ratified by her 1996 Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album after dozens of country nods from the Recording Academy.

Her subsequent band, Spyboy, featured Buddy Miller’s own virtuosic guitar and retained bassist Johnson and drummer Brady Blade, documented with a live album in 1998 (to be re-released this November with bonus tracks; available here), rejoining Lanois that same year as a featured vocalist on Willie Nelson’s own moody Lanois-produced Teatro. Willie wasn’t the only icon Daniel Lanois tackled that year. The Canadian manned the board again for Bob Dylan, casting stygian shadows over Time Out of Mind, his triumphant return to glory with platinum sales and multiple Grammys.

Following a duet project with Linda Ronstadt and the belated release of Trio II alongside Ronstadt and Dolly Parton, Harris signed with Nonesuch Records, then welcoming eclectic roots and rock talent that had chafed within Warner’s mainstream labels. On Red Dirt Girl, released in 2000, Malcolm Burn took over production with a freshly inspired Harris writing or co-writing 11 of its dozen tracks, rendered in arrangements carrying the new textures of Wrecking Ball forward and earning another Grammy.

Emmylou Harris would revisit country elements on subsequent live and studio cameos, as well as with Crowell and Mark Knopfler for duet projects while her wider stylistic perspective has since consolidated her stature as an Americana icon. In February 2025, the Recording Academy confirmed that Wrecking Ball was being inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in recognition of its impact.

Watch Harris and Lanois perform “Where Will I Be” live in London in 1995

Wrecking Ball is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. Harris’ vast catalog is available here.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.