The Vaults: An Interview with Twang Guitar Innovator Duane Eddy

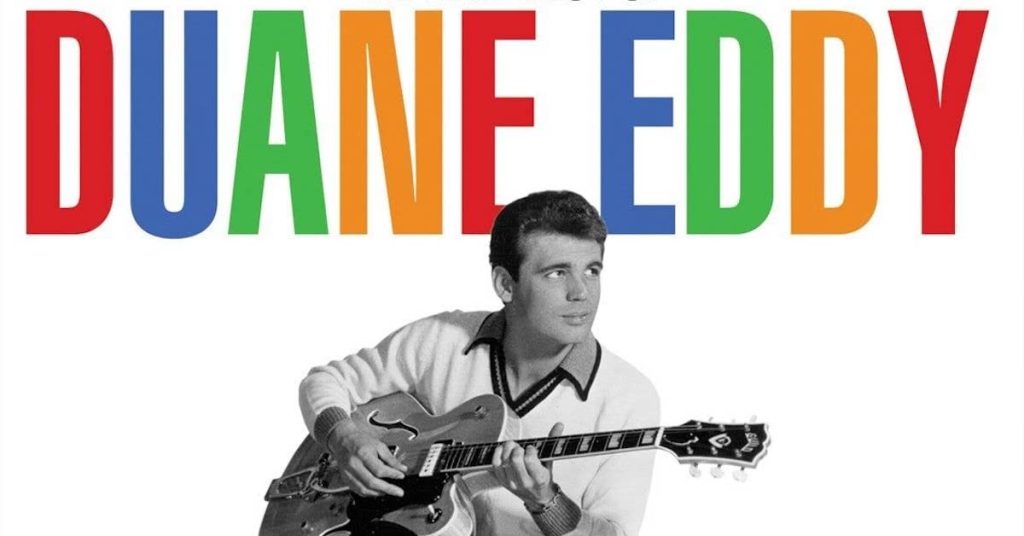

by Jeff TamarkinJohn Fogerty called him “the first rock ’n’ roll guitar god,” and he wasn’t the only musician influenced by Duane Eddy, who died on April 30, 2024, at age 86: The Beatles and Bruce Springsteen were fans too, and among those paying tribute to Eddy upon his passing were BTO/Guess Who guitarist Randy Bachman, bluesman Joe Bonamassa and singer Nancy Sinatra. Eddy’s influence spanned generations and genres.

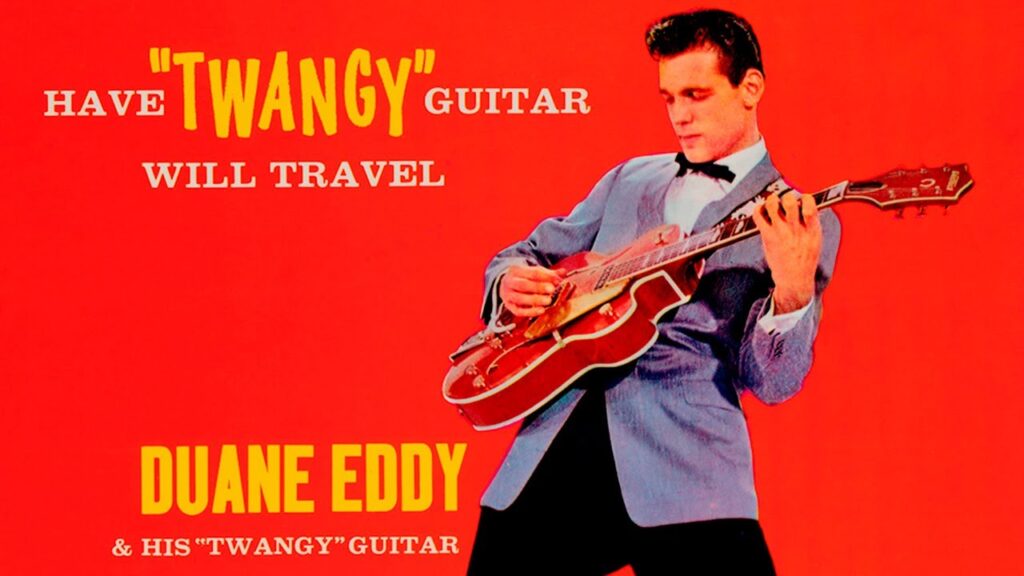

Eddy’s trademark “twang” sound helped to define rock ’n’ roll guitar in the late ’50s, and earned him a coveted slot in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, to which he was inducted in 1994. Writing on Eddy for the program booklet for that year’s induction ceremony, Michael Hill said, “Twang came to represent a walk on the wild side, late ’50s-style: the sound of revved-up hotrods, of rebels with or without a cause, an echo of the wild west on the frontier of rock ’n’ roll. It was the battle cry of the early guitar hero, embodied by the lean and handsome Eddy, who arrives in town slinging a guitar like a gun. He didn’t need to speak or sing; he said it all with his terse playing.”

Eddy’s career had its ups and downs, to be sure. Despite his continuing influence, he fell out of favor commercially in the late ’60s, and ceased making albums for two decades. Nearly another quarter-century then passed until, in 2011, he released Road Trip, which became his final studio album. It was then that future Best Classic Bands editor Jeff Tamarkin spoke with Eddy about his hits and his place in rock history. Most of the following interview, which we’ve condensed to focus on Eddy’s early history, has never before been published.

Best Classic Bands: You’ve been asked this question more than any other, I’m sure, but please indulge us one more time: How did you come up with your trademark twang sound?

Duane Eddy: It developed because I got tired of hearing those rock ’n’ roll licks on the high strings. It was always the same thing—except for [Elvis Presley guitarist] Scotty Moore, of course, who did different things. I thought, play down low, try that. I also knew from the few sessions I’d done that the low strings recorded stronger and more powerfully than the high strings. For rock ’n’ roll we need a little more power: Chuck Berry defined rock ’n’ roll guitar to me. Then I came along and I had to come up with something different.

You were born in upstate New York but spent your teens in Arizona. What was that change in location like for you?

I moved out there when I was 12. I just fell in love with the desert. It was so big and open. I used to ride my bike out there. I think something about the bigness may have subconsciously worked into [my sound].

You’re associated with the Gretsch Chet Atkins model guitar. Why that one?

I started out with a 1954 gold top Gibson Les Paul. I traded it in on the Gretsch in 1957 because I wanted a vibrato.

One man in particular was very important to your early career, producer Lee Hazlewood. Can you talk about how he contributed to your music?

I met Lee Hazlewood when I was going to high school in Coolidge, Arizona. He came to Coolidge, which has a local radio station. He’d just got out of broadcasting school, where he’d been learning to be a disc jockey and an announcer. They placed him in the town of Coolidge, and he hit the ground running. Pretty soon everybody was listening to him and commenting on him and a friend of mine who also wanted to be a DJ took me out there to the transmitter and said, “You gotta meet this guy, he’s a hoot.” So I went out and met him and there was Lee Hazlewood. Another guy and myself, Jimmy Delbridge, who later [recorded as] Jimmy Dell, we sang together. Lee came around and heard us sing and took us up to Phoenix and acted as our manager, because he wanted to move to a bigger radio market. We sang and they liked us and I started sitting in with a band there on Saturday nights, and when the guitar player left I got the gig. We played dances and honky-tonks and clubs and TV shows for the next few years. Lee tried a little recording of Jimmy and I singing together on songs that he’d written, which were his first attempts to write and produce and our first attempts at recording. That’s where we started in 1955.

Listen to Jimmy and Duane’s “Soda Fountain Girl” from 1955

You’re obviously not known as a singer. Why did you stop?

I really loved it, but I just didn’t have the great voice for it. Maybe I could have developed it. I was kind of a poor man’s Ricky Nelson.

Related: 10 great instrumental hits of the ’60s

How did you and saxophonist Steve Douglas, who also contributed so significantly to your sound, find each other?

Steve was the first sax player I ever worked with on the road. We used session guys on the records. His big contribution came one day when he said, “Guess what, I learned ‘Peter Gunn’ last night.” I said, “Well, that’s nice,” and I wondered why he thought I would care. He said, “Well, I thought maybe we could record it.” I said, “There’s not much for me to do on it, Steve.” We were doing my second album and we had 11 songs but in those days we had 12 songs on an album. Lee and I were trying to figure out what to do for the 12th and [Steve] said, “What about ‘Peter Gunn’?” Lee looked at me and said, “Well, what do you think?” We didn’t have anything else so I thought I could add a little intro thing and put some vibrato in front and have a break in the middle and do it again. We did that and we rocked out on it. [The single reached #27 in 1960—ed.]

What’s the story behind your first top 10 hit, “Rebel Rouser”?

I wrote “Rebel Rouser” one morning in March of 1958. I had “Movin’ ’n’ Groovin’,” which had gotten in the charts [#72—ed.] and gave me a little confidence, and the record company said to go back and do something else. So we all got together in the studio one March morning and I had the drummer play an afterbeat and I had this idea where I pictured in my mind a gang walking down a dark alley toward you. I put that all together and came up with that first part of “Rebel Rouser,” with nothing but me, and then the band comes in and then I modulate it because we don’t have a bridge or anything to change it. We knew we needed an answer on it, like a sax or something. [Hazlewood] took the track over to Gold Star Studio in Hollywood, which had a great echo. We only had three tracks at the time—one for me, one for the band and one for the overdubs. So we got over there and the band track was mixed so we could either turn it up or down but that’s it. Then he overdubbed the Rivingtons—the Sharps, they were called then—who I’d met at this rock ’n’roll show in L.A. They did the oohs and ahhs and the handclaps and started yelling during one take and Lee said, “Leave that in.” And he had Gil Bernal, a sax player from L.A., who was one of the top session men at the time. He had a real sleazy and funky sax sound. Gil put the sax on and Lee ran it through the Gold Star echo and combined it with the Phoenix echo and when he sent the track back to me I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I played it over and over. Then they picked “Stalkin’,” the B-side, to be the A-side. Nobody played “Rebel Rouser” for the first two weeks. Dick Clark too. Then somebody turned it over and we got it sorted out.

What about “Forty Miles of Bad Road”?

I just walked in one day and Bob Taylor, the drummer, and Al Casey, the guitar and bass player, played piano on some of the sessions, bass, rhythm guitar. He and Bob tossed around this idea for “Forty Miles,” and I sat down and worked with it for a while and changed a bunch of stuff and added a bunch of stuff. Steve was there at the time so we could do it live. All they had to do was overdub the yells right before they mixed it.

The biggest chart record you had was “Because They’re Young.”

Don Costa, Wally Gold and Aaron Schroeder wrote that. Dick Clark had come to Lee and I and said, “Write something for this movie. It’s called Because They’re Young.” We were trying to think of ideas that would make a good movie theme and Lee was also a producer there and other people were submitting songs for this movie for me. They knew I was gonna do it so they wrote some stuff and submitted it to Lee, who had an office in Hollywood by this time, in 1960. A lot of stuff came in and he came upon this song one afternoon and he thought, “Oh my God, I just love this.” He played it over and over again for three hours, kicking it around and figuring out how to do it. We went in the studio with a great little band. They had Shelly Manne on drums, the great jazz drummer. Barney Kessel was there, and Howard Roberts, both fine jazz guitar players. And then the L.A. Philharmonic came filing in. I was one of the first people to use strings on a rock ’n’ roll record.

When the British Invasion happened in 1964, how did that affect your career?

It changed everything. But I’d been on the road for five years by then. When the Beatles came along I thought, “Gosh, what a good little garage band.” I had no idea it was going to be as huge as it turned out to be. When the Beatles came along in February ’64, I was busy in the studio. I was still having chart records but it was starting to wane at that point. I was supposed to open for the Beatles but Roy Orbison did instead.

You met Elvis. What was he like?

I met him in 1971. I was totally knocked out with him. He was everything I wanted him to be.

You were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. One of the people who was advocating for you was John Fogerty. He made a case for you with the Hall’s nominating committee.

I didn’t even know that he had done that. I had heard that he’d talked to some people up there. The story I heard was that they threw him out because they didn’t want his interference.

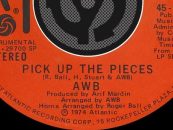

Listen to Eddy’s remake of “Peter Gunn” with the Art of Noise from 1986

Watch Eddy perform “Rebel Rouser” on Late Night with David Letterman in 1985

Many of his recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationCheck out the album cover for “Especially for You”. Looks like Duane is at one of the many Depression-era “buildings” (known as “lookouts” here) in South Mountain Park, in South Phoenix.

I had no idea that Duane was married to Jessi Colter many years before she married Waylon.

History is so-o fascinating.