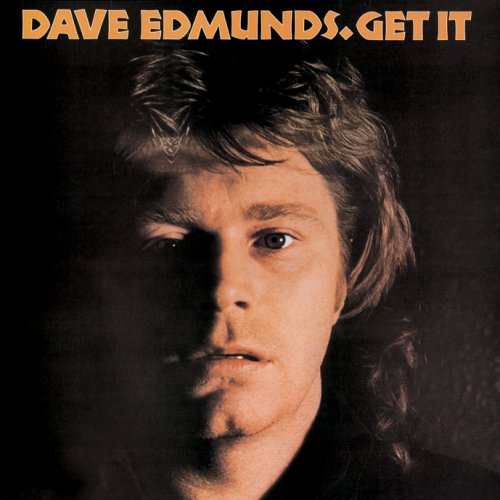

By the time the prodigiously talented Welsh musician Dave Edmunds signed to Led Zeppelin’s just-launched Swan Song label in 1976 at the behest of superfan Robert Plant, his reputation as a master guitarist and out-of-control raver was well known. With the group Love Sculpture (“Sabre Dance”) and as a solo act, Edmunds had serious success on the British charts, including his #1 remake of Smiley Lewis’ 1955 hit “I Hear You Knockin’” (which also reached #4 in the U.S.) and two spectacular recreations of Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” that made the top 10, “Baby I Love You” and “Born to Be With You.”

By the time the prodigiously talented Welsh musician Dave Edmunds signed to Led Zeppelin’s just-launched Swan Song label in 1976 at the behest of superfan Robert Plant, his reputation as a master guitarist and out-of-control raver was well known. With the group Love Sculpture (“Sabre Dance”) and as a solo act, Edmunds had serious success on the British charts, including his #1 remake of Smiley Lewis’ 1955 hit “I Hear You Knockin’” (which also reached #4 in the U.S.) and two spectacular recreations of Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” that made the top 10, “Baby I Love You” and “Born to Be With You.”

For many years, Edmunds could often be found working alone all night at Rockfield Studios in rural Monmouth, Wales, playing drums, keyboards and bass, plus singing, doing his own engineering and overdubbing as many as 40 guitar tracks into a single mix. As dozens of “pub-rock” acts played venues in London, Edmunds stayed out of the center of action, doing his own roots-rock work on his own.

As the Ducks Deluxe/Graham Parker and the Rumour member Martin Belmont told writer Will Birch, “There were more myths about Edmunds than was humanly possible. He had a big house in Monmouth, his chemical intake was massive, he would drive his Jaguar at 90 miles an hour through country lanes on Mandrax and whiskey, with his vintage Gibson ES-335, out of the case, on the back seat. In the studio, he would listen to playbacks at a deafening volume and squeeze the EQ up so far that people’s trousers would rustle.”

It wasn’t until he moved to London in ’76 that Edmunds began to work at the tiny 16-track studio Pathway in Highbury with a different attitude about recording. As he told the New Musical Express’ Nick Kent, “I was using the business as a hobby when I should have been making it a career all along.” Instead of spending dusk-to-dawn recording a 15-second guitar part to perfection, he learned to be more judicious and quick, collaborating with other musicians and taking outside input.

This new style chimed well with Edmunds’ increasingly important relationship with producer-bassist-singer-songwriter Nick Lowe, who was known as “Basher” for the speed of his recording sessions. As Lowe explained to writer Dave Schulps, he was one of Edmunds’ few good mates in London: “I’d go down to the studio with him and just sit there. He’s taught me so many things. He thinks my ideas are off-the-wall and I always tell him he’s living in the past. We have arguments, but then I only argue with friends.”

The album Get It, released in April 1977, was mostly the result of these comparatively rapid Pathway sessions. The core trio was Edmunds, Lowe and drummer Terry Williams; they’d soon to morph into Rockpile by adding guitarist Billy Bremner. On Get It, Edmunds also got instrumental support from bassist Paul Riley (of pub-rock stalwarts Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers), drummers Steve Goulding and Billy Rankin, and keyboardist Bob Andrews (all from the Brinsley Schwarz/the Rumour nexus).

Although he co-wrote the occasional song, Edmunds depended on his skill at resurrecting treasured hits of the past, and finding contemporary writers informed by a similar devotion to Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Eddie Cochran, etc. He loved the rockabilly sound of “a string bass slapping away with an acoustic guitar and an electric picking away.” The Faber Companion to 20th Century Popular Music rightly calls Edmunds “A curator of the museum of rock ‘n’ roll.”

Related: Dave Edmunds shares two Chuck Berry stories

The LP begins with the roar of Bob Seger’s “Get Out of Denver,” which originally led off Seger’s 1974 album Seven. The tongue-twisting Chuck Berry-inspired lyrics are handled by multiple Edmunds harmony vocals, and overdubbed guitars keep it pumping: “I still remember it was autumn and the moon was shining/Our ’60 Cadillac was roaring through Nebraska whining/Doing 120, man the fields was bending over/Heading out for the mountains knowing we was traveling further.” It’s an explosive 2:17, announcing that for this LP the gloves are off and the frills will be few.

Nick Lowe’s exuberant “I Knew the Bride,” riffing on the melody and storytelling of Berry’s “You Never Can Tell,” keeps the pressure up with a fast shuffle. Starting with a galvanizing “Well!” borrowed from Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-A-Lula,” Edmunds somehow manages to keep his vocal relaxed on the verses and urgent on the choruses. His 10-second guitar solo at 2:11 is a lesson in rockin’ concision. The lyrics are relentlessly clever, tucked carefully into a careening melody: “The proud daddy only want to give his little girl the best/So he put down a grand on a cozy little lover’s nest/You could have called the reception an unqualified success/At a posh hotel for a hundred and fifty guests.” The clear production reveals Edmunds’ knack for leaving space for every detail, even when he’s layering dozens of parts.

Graham Parker cut “Back to School Days” for his debut album a few months before Edmunds tracked his version, featuring many of the same musicians. Edmunds might get the edge for increasing the rockabilly swing and an impressive lead vocal.

The Lowe-Edmunds co-write “Here Comes the Weekend” is a brilliant two-minute Everly Brothers homage with Edmunds doing all the singing, although he and Lowe in later Rockpile shows would harmonize it together. Lowe says they originally wrote it down on the back of a cigarette pack backstage at the Nashville Rooms nightclub.

The only solo Edmunds composition on the set, “Worn Out Suits, Brand New Pockets,” is his tribute to George Jones and Buck Owens, given the phrasing and faux Texas accent. It begins with a killer opening couplet, “They say money is the root of all evil/But if that’s so, they should make a saint of me,” and has a pedal steel part to die for. Edmunds’ vigorous take on Hank Williams’ “Hey Good Lookin’” on the second LP side is his other splendid country salute.

In 1960 Dion and the Belmonts cut a hit version of the Rodgers-Hart classic “Where or When,” from the Broadway show Babes In Arms, and Edmunds can’t resist replicating it on his own terms, eliminating the interfering saxophone and focusing even more on the stacked harmony vocals. It’s a downbeat ending to a rollicking LP side. If you want to criticize Edmunds for living in the past, this might be an example of him satisfying his yen for nostalgia without much oomph.

Penned by Jim Ford and Lolly Vegas, “Ju Ju Man” was recorded by Lowe’s old band Brinsley Schwarz in 1972; Edmunds cut this version at Rockfield in 1975. The longest track on the album, it chugs along nicely, and features an accordion break from Bob Andrews, followed by another pithy Edmunds solo, about a minute in. The Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps “Git It” single from 1958 gets a title alteration here, and Edmunds pulls out all the doo-wop stops for a rousing vocal and instrumental performance, with a vintage echo on the lead singer. It’s tremendous fun.

“Let’s Talk About Us” is an Otis Blackwell song originally cut by Jerry Lee Lewis for Sun in 1959. Naturally, Edmunds leads with guitar instead of piano, nixes the original’s female vocal chorus, and roughens his voice from time to time for a grittier high-tenor performance than Lewis delivered. Lewis’ concluding ad-libbed “C’mon, sugar” is retained. It is not sacrilege to suggest Edmunds’ version is way better than the original.

Lowe’s “What Did I Do Last Night” is taken at a faster pace than seems possible, even on an album full of speedy tempos. It sounds like Andrews is doing the Jerry Lee Lewis piano pounding on this one, the album’s shortest cut. Lowe-Edmunds’ luscious “Little Darlin’” slows things down, evoking Del Shannon and Frankie Valli, two of Edmunds’ early-’60s templates.

Get It ends with “My Baby Left Me,” the Arthur Crudup tune made famous by Elvis, in a brief version cut back in 1969 by Edmunds and members of Love Sculpture, a Rockfield leftover with the Sun energy that Edmunds can nearly always be found chasing. A terrific version of “New York’s a Lonely Town” (a minor U.S. 1965 hit for the Tradewinds) cut at Pathway was only used as a B-side, as was another Edmunds-Lowe tune in a Beach Boys-Spector mode, “As Lovers Do.”

Get It sold better in Australia and Scandinavia than it did in the U.S. or England; it didn’t throw off any successful singles despite Swan Song’s attempts to garner airplay. Edmunds’ subsequent albums for Swan Song were just as solid, but his 1979 version of Elvis Costello’s “Girls Talk” was as close as he came to another chart breakthrough. In 1983, a Jeff Lynne song “Slipping Away” became Edmunds’ last Top 40 American hit when it managed a single week at #39 on Billboard’s chart.

Listen to the single-only “New York’s a Lonely Town”

Through decades of semi-retirement and health challenges, Edmunds has only emerged sporadically for guest TV appearances or live shows, including a 2000 stint with Ringo Starr and His All-Starr Band. His last studio album was the instrumental On Guitar…Dave Edmunds: Rags & Classics in 2015. He and Lowe reportedly had a falling out years ago and don’t communicate. Sadly underappreciated beyond a cult of music devotees, he turned 81 years old on April 15, 2025, apparently living quietly somewhere in Europe. He gave his final performance in 2017.

Edmunds’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Rockpile, with Edmunds and Nick Lowe, perform “I Knew the Bride” Live

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.