The truest moment in an evening full of truths came from the audience. For two hours on September 19, 2016, the first of two nights at New York’s Beacon Theatre, Cat Stevens—in his first New York concert since the mid-’70s—had been recounting the pivotal moments in his life and career, his stories bridging a stellar, marathon presentation of songs. He was well into the late 1970s—the decade of his greatest popularity—when he came to the tale of his spiritual awakening. He was being carried out to sea by the strong ocean current in Southern California, Stevens recalled, when he asked for and received help from God. He was led to Islam: Stevens converted in 1977, changed his name to Yusuf Islam the following year and withdrew from the music world in 1979.

It didn’t all go the way he had hoped, Stevens admitted to the Beacon audience, likely (but not specifically) alluding to the criticism leveled against him a decade later when he announced his support of a death fatwa against author Salman Rushdie, whose book The Satanic Verses had incensed Muslims worldwide. “There was anger and misunderstanding” among his fans, Stevens confessed.

A lone voice cried out from the orchestra: “We’re sorry!”

Stevens—who is billed as Yusuf/Cat Stevens on this tour, which he is calling “A Cat’s Attic”—laughed and said he too had forgiven. It’s not that there had been any tension between him and the fans inside the sold-out theater—it had been a two-way unconditional love fest from the second he’d walked onstage. If there had been any lingering animosity, then the unofficial audience spokesman’s impromptu apology would have been the ideal icebreaker. But Stevens’ induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014 had already let him—and the world—know that the healing was complete.

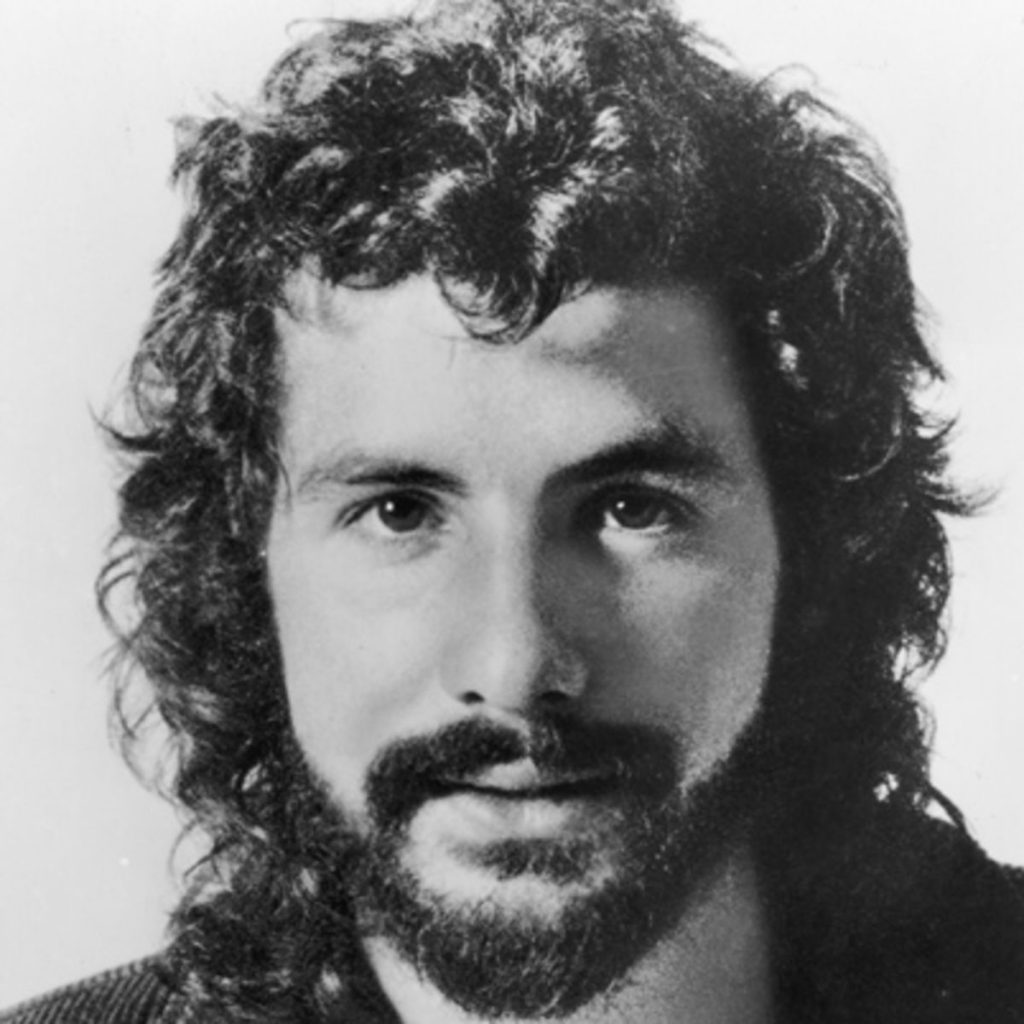

Cat Stevens at the Beacon Theatre, NYC, Sept 19, 2016, in our live review (Photo: Gail Heaslip; used with permission)

Cat Stevens’ story is surely one of the most unusual in rock. Born Steven Demetre Georgiou in London on July 21, 1948, he grew up on classical music and show tunes (he performed “Somewhere” from West Side Story early in the evening) before, like everyone else, the Beatles turned him inside out (to illustrate that, he sang “Love Me Do”—and played the Fabs’ “Twist and Shout” on a vintage turntable). Stevens began writing his own songs 50 years ago, and his first charting single in England was the whimsical “I Love My Dog” (also played here) in October 1966.

“Matthew and Son,” the following year, rose to #2 in the U.K. and that same year a song he had written, “Here Comes My Baby,” became a hit for the Tremeloes in both the U.K. and the United States. Another song he wrote and released in 1967, “The First Cut Is the Deepest,” later became a hit for Rod Stewart. He was on his way.

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

Cat Stevens at the Beacon Theatre, NYC, Sept 19, 2016, in our live review (Photo: Gail Heaslip; used with permission)

Those early tunes, each punctuated by a story (an amusing one told of touring with Hendrix and being exposed to some unnamed but presumably potent substance), were used to set the scene. It wasn’t until the turn of the decade that he evolved into Cat Stevens as we came to know him—a gifted, low-key singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist—and it was the songs of that era, mostly situated in the second set, that understandably received the most enthusiastic response. Performing in front of a mockup of a cozy country shack, accompanied by guitarist/harmony vocalist Eric Appapoulay and bassist Kwame Yeboah (who also supplied light percussion), Stevens stuck largely to acoustic guitar—an instrument on which his considerable skills were magnified in the live setting—with a few forays over to the piano. As the stage set suggested, it was all very up close and personal.

Most of the major hits and FM radio classics were saved until the second set or the encore: “Peace Train,” “Morning Has Broken,” “Oh Very Young,” “Father and Son,” “Moonshadow” and “Wild World” all came after the break, sung and played to near perfection.

They’ve all held up remarkably well, too: Stevens’ vocals have suffered no degradation since we last heard him sing these songs four decades ago. He gave them all of the intimacy and nuance—and soulfulness—he’d brought to them when they were brand new.

Despite the predominantly chronological sequencing, though, this was not solely a night of greatest hits. Stevens performed more than 30 numbers in all, and he was unafraid to reach into his considerable catalog. He opened the show with “Where Do the Children Play?,” the leadoff track from Tea for the Tillerman, his top 10 breakthrough album of 1971, and while it’s hardly obscure it was an inspired choice nonetheless, setting the upbeat, celebratory tone of the first half. It was followed by “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out,” written by Stevens for Tillerman but left off the album, first turning up in the ’71 film Harold and Maude. “Katmandu,” from 1970’s Mona Bone Jakon, “Sitting” and “Boy With a Moon and Star on His Head,” both from Catch Bull at Four (1972), and even “Novim’s Nightmare,” from 1975’s lesser known Numbers, were among the deeper cuts that Stevens pulled out on this evening.

[Stevens returned to the stage for several dates in 2023 and released a new studio album, King of a Land. If he tours again, tickets will be available here and here.]

A couple of highlights had nothing to do with Cat Stevens’ recorded canon though. The first, a touching reading of the Impressions’ spiritual ballad “People Get Ready,” perfectly illustrated Stevens’ own move into his faith.

Then, coming out of “Maybe There’s a World,” a song he recorded as Yusuf on An Other Cup in 2006—his first album of secular music since 1978—Stevens segued into “All You Need Is Love.” It was left to the Beatles, who had inspired him so long ago, to sum up the message that had hovered so thickly in the air all night. It was a sentiment that, we realized anew, was always at the root of Cat Stevens’ music.

Watch him perform “Peace Train,” a few days earlier

Speaking of his decision to return to his classic repertoire and tour behind it after such a lengthy absence, Stevens said, “I realized I still had a job to do.” We’re glad, because he still does it so well.

[His extensive catalog, with many expanded editions, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Related: Listings for 100s of classic rock tours

- Bobbie Gentry ‘Ode to Billie Joe’: Another Sleepy, Dusty Delta Day - 07/10/2025

- Full Cyrkle: The ‘Red Rubber Ball’ Band Bounces Back - 07/09/2025

- When Brownsville Station Were Smokin’ - 07/05/2025

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI read your review and was surprised at your rather one sided view of the controversy surrounding Mr. Stevens comments supporting the death fatwa against Salman Rushdie. The only subsequent remarks clarifying those comments that I have heard was when he said something like he was only quoting the Koran and implied that he was not personally calling for Mr Rushdie death.

Although I have not read the Koran, I’m sure that like the Bible, it contains many statements that seem to hold contradictory opinions about an issue thus allowing a reader to quote the statement that backs up there own personal belief. Since Mr Stevens never specifically condemned the fatwa calling for the murder of Mr Rushdie, I don’t see why anyone who criticized his statements has any need to apologize. If anyone reading my comments can point me to any other statements by Mr Stevens, where he did voice such opposition, I would be happy to view them. Finally if the article had simply focused on his music and not mentioned this controversy I would not have felt the need to comment on the controversy. In short the article first mentioned the issue and then backed off of any kind of balanced view of it.