Carlos Santana, Violinist? Fate Had Other Plans: Book Excerpt

by Jeff Tamarkin

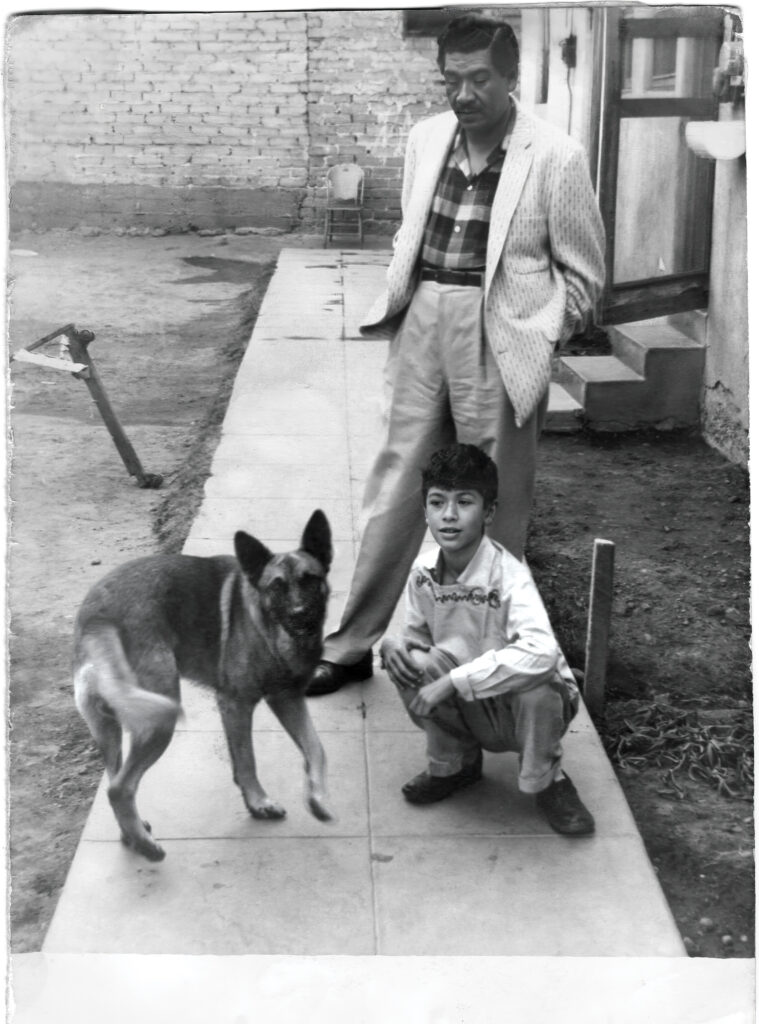

Carlos Santana (3rd from right) with his father’s mariachi band (Photo courtesy of Insight Editions)

In the just-published book Carlos Santana: Love, Devotion, Surrender—The Illustrated Story of Santana’s Musical Journey (Insight Editions), the story of one of the world’s most beloved and honored musicians is told in vivid detail for the first time, with input from Santana himself as well as his management, former and current band members and many others.

The book, written by Best Classic Bands’ editor Jeff Tamarkin and totaling more than 400 oversized pages, includes a complete discography and gig guide, brand new interviews with Carlos, band members past and present, and associates such as Clive Davis, Steve Miller and John McLaughlin, plus a foreword from Taj Mahal. It also features hundreds of photos—many never before published—among them dozens of images of Carlos throughout all stages of his career, along with numerous pictures of everything from Santana‘s guitars to concert ticket stubs, album covers (several reproduced as pullouts), concert posters and much more.

The biography covers the Mexican-born guitarist’s life from birth to the present day, revealing, among other stories, how he evolved from being a street kid in Tijuana playing music for pesos to an international, multi-Grammy-winning icon. In this exclusive except from the book, we read about his humble beginnings as a violinist—yes, a violinist!—whose main goal was not to be an expert player but to please his father, himself a celebrated musician.

He would soon trade in that violin for a guitar, and embark upon a lifelong quest for higher truths, but first he had to pay some dues.

Here is the story of the young Carlos Santana, reluctant violinist, as told in Carlos Santana: Love, Devotion, Surrender—The Illustrated Story of Santana’s Musical Journey. The book, published on May 27, 2025, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

****

If fate had not intervened, this book might have been about a violinist. There’s a good reason it isn’t: Try as he might, after several years of making the effort, even gaining enough proficiency to pocket a few pesos scratching out a tune on the street, Carlos Santana still didn’t think he played the instrument very well. He came to hate it.

“I sounded like a pussycat in the alley, like a cartoon,” Carlos said more than six decades after his hapless labors finally came to an end. “I didn’t want to sound like that. I said, ‘No matter what I do, I can’t make it sound pretty like my dad does.’ But the guitar was easy for me.”

So, instead of recounting the story of a successor to Jascha Heifetz or Yehudi Menuhin, this book tells the tale of a man who obviously made the right decision by switching his allegiance to another stringed instrument. Today, and for more than 50 years, the name Santana is revered around the world, synonymous with a distinctive sound, feel, style and attitude—and a remarkable body of work that has entranced millions. Picture Carlos Santana in your mind, head tilted back, eyes shut, lost in the music, and then try to imagine a bow in his hand and a violin resting upon his shoulder. You can’t, right?

But this story does start with that four-stringed acoustic instrument, and the Mexican boy who couldn’t seem to get the hang of it.

Carlos Humberto Santana—the surname derives from Santa Anna, or Saint Anne, grandmother of Jesus—was destined to become a musician. His father, José, born in Jalisco, Mexico, in 1913, had learned to play the violin from his own father, Antonino. José turned professional, joining, and later leading, a symphony orchestra before realizing that there was more opportunity in mariachi, boleros and other homespun varieties of traditional Hispanic music.

Carlos’ mother, Josefina, c. 1951 (Photo courtesy of Insight Editions)

One fan of José’s was Josefina Barragán, also of Jalisco. As Carlos recalled in his 2014 memoir, The Universal Tone, Josefina “knew that would be the man I would marry and leave this little town with.” She and José became husband and wife in 1940, eloping when he was 26 and she 18. They settled in Autlán, where they began producing baby Santanas—four girls and three boys in all. Carlos, born July 20, 1947, was the middle child; his younger brother, Jorge, who would also become an accomplished guitarist, followed four years later.

“Dad lived to play, and he played to live,” Carlos wrote in his memoir. “That’s what musicians are meant to do.”

Throughout the early ’50s, mainly because his father’s occupation took him away from the small town the Santanas called home, Carlos saw less and less of his dad; José spent most of his time north in the bustling border city of Tijuana, where a musician could find steady work. At first, Josefina and the Santana children stayed behind in Autlán, but in 1955 the rest of the family decided to join José in Tijuana. A five-day car trip, sleeping in the desert and eating at truck stops along the way, took them to an address in Tijuana where, Carlos later recalled in his memoir, they found José shacked up with a prostitute.

“Eventually, Dad left the other woman, and we were all together again,” Carlos wrote, but life in the teeming city proved excessively difficult at times. “It was so hot we couldn’t sleep,” he remembered. “We were tired and cranky all the time. We had no money at all. We were hungry.” Young Carlos vowed that someday, when he was older, he would buy his mother her own house, complete with a refrigerator and washing machine. “Of course I didn’t know then how I was going to do it,” but 15 years later he made good, using the royalties from the first Santana album to buy a home for his parents.

That was still only a dream, of course, and Carlos’ childhood was demanding—he began working at a very young age, chipping in to help support the family and becoming, in his own evaluation, a street kid, surviving by his wits. “I soon learned that there was a way to walk those streets,” he wrote, “a different kind of walk. Without disturbing anybody, you could project an attitude of ‘Don’t mess with me.’”

FROM VIOLIN TO GUITAR

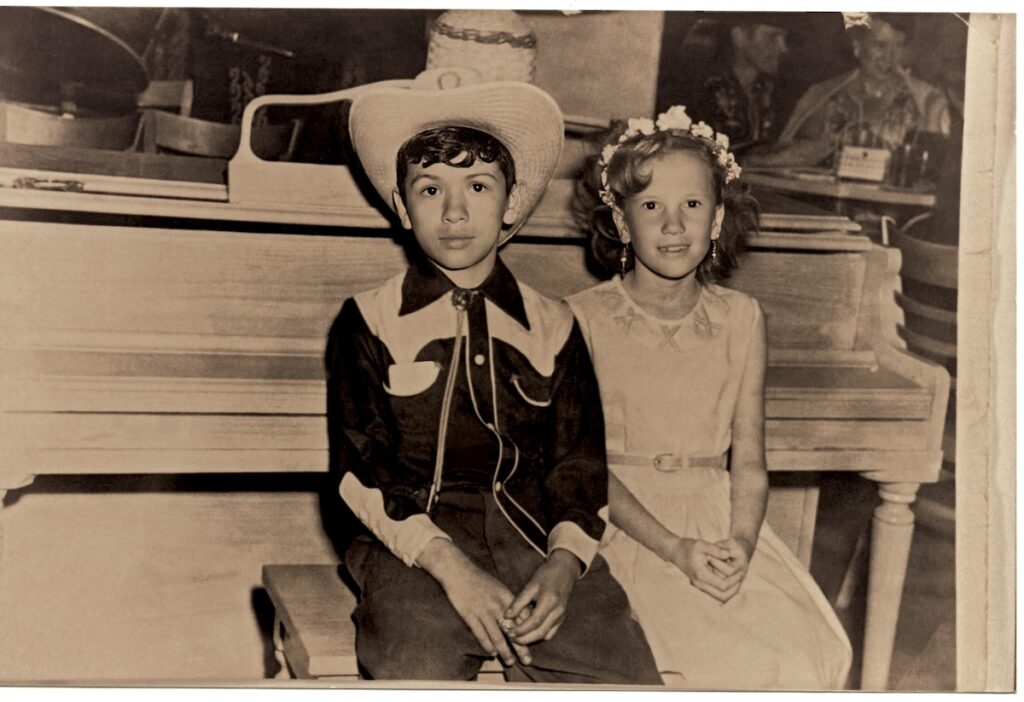

Carlos (center) in an early band with Danny Haro on drums and Sergio “Gus” Rodriguez on bass, Tijuana, c. 1962 (Photo courtesy of Insight Editions)

There was music all around, and Carlos picked up on the various sounds wherever and whenever he could. Listening to José’s band—violin, contrabass, accordion, piano and cello—Carlos realized, he later said, “that what I love about music, since the beginning, is the long, long beautiful notes without vibrato.”

His father took notice of the boy’s interest, and when Carlos was eight, José decided it was time for his son to take up an instrument. Carlos tried the saxophone, but when that didn’t pan out (he didn’t like the way it felt in his mouth), a violin found its way into Carlos’ hands. Every day after school, he took lessons, which were augmented by José’s own teachings. It didn’t always go well.

Despite his distaste for the violin and the later self-effacement, Carlos did grow adept enough on the instrument to team up with two brothers who played acoustic guitars and performed for money on the street, taking requests from tourists. He even entered music contests in Tijuana, sometimes winning prizes. By the time he was 10, Carlos occasionally sat in with José’s mariachi band. It wasn’t until 1961, now into his teenage years, that Carlos finally put down the violin for good.

The timing of Carlos’ rejection of the violin was not coincidental: Rock and roll, R&B and blues, wafting over the airwaves from north of the border, had caught his ear. One after another, new names—B.B. King, Ray Charles, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Little Richard, T-Bone Walker, Lonnie Johnson—entered his consciousness. His sisters monopolized the Santana family phonograph with their Elvis Presley records, but Carlos wasn’t moved by the so-called King of Rock and Roll. He dug deeper, discovering the music that inspired Elvis. That music, he felt, came from the heart and soul; in those sounds, Carlos Santana heard truth, passion, life.

Carlos made a valiant effort to learn the violin, but it was not his love for the fretless instrument that drove him as much as his desire to please his father.

“My dad was a good teacher,” Carlos recalled in the memoir, “but he wasn’t necessarily gentle. He would push me, and then the shouting would come, and I would start crying.”

Naturally, there was still plenty of Mexican music all around, and Carlos was expected—required—to play it, but, “I just never connected with it,” he wrote in his book. “It felt like wearing somebody else’s shoes.” It wasn’t until years later that he understood it wasn’t the music itself that turned him off; it was the association with his “painful, hard times with Mom and Dad.” He came to appreciate the music of his native country in adulthood, but as a youth, his antennae were pointed north, where his American counterparts were tuned in to different kinds of music than Carlos was hearing at home.

There was one exception, however: Javier Bátiz. A Tijuana-born guitarist only three years Carlos’ senior, Bátiz was playing music in a park when Carlos first came upon him. The sound captured his attention immediately, a “boogie kind of beat with echo, echo, echo—just bouncing off the buildings and trees.” Bátiz and his band, the TJs, had “funky amplifiers and electric guitars and a booming bass,” and the leader himself was wild-looking, “his hair piled up in a big mop. It was like a UFO had landed in my backyard,” Carlos recalled years later. “I remember thinking,” he wrote in The Universal Tone, “this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of Santana’s classic Abraxas

That wasn’t going to happen if he remained a violinist, and, luckily for him, his mom knew what had to happen next. She wrote to José, who by then had been living in San Francisco for nearly a year. Their son wanted to learn the guitar, Josefina told her husband. It would be a nice gesture if he would buy one for the kid.

“The friends I hung around never listened, with all respect, to Elvis Presley or any of that. That’s an art in itself, and he learned a lot from Black people, but the delivery didn’t touch me. I wanted the other stuff. I wanted John Lee Hooker.”—Carlos

Carlos soon found a Gibson electric guitar and amplifier waiting for him. He wasted no time figuring out how to get some noise out of it.

“All of the guitar players that I love, they have this thing where they feel what they feel. A lot of people don’t feel what they feel. It’s like a parrot repeating a prayer; they don’t know what they’re saying. When a musician feels what they’re feeling, it sounds different. So for me, it was easy to go on the guitar and feel what I was feeling.” —Carlos

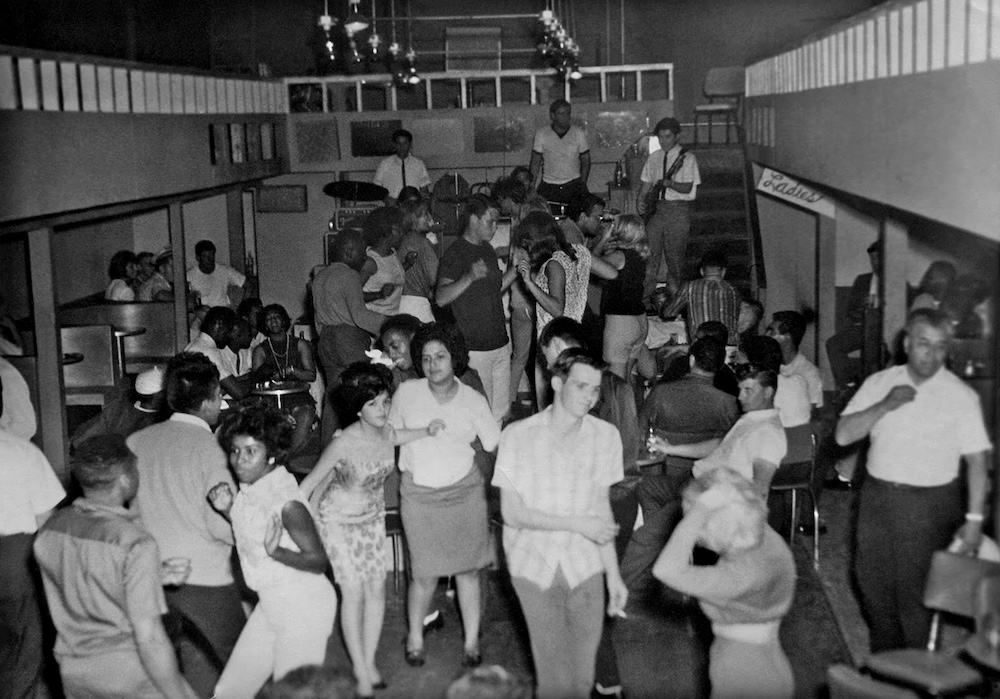

Carlos was a quick study. He filled his head with electric guitar music—recordings by instrumental outfits like the American band the Ventures and England’s Shadows—and was able to sit in with Bátiz and the TJs, figuring out how to play bass guitar simply because that’s what they needed at the time. He learned how to play songs by R&B and blues greats—James Brown, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Bo Diddley, Otis Rush, Lightnin’ Hopkins and many others. By the end of 1961, Carlos was a working musician, playing guitar in the house band at a Tijuana nightclub called El Convoy.

“As time went by, I got more and more into the blues—Black blues,” he wrote in the memoir. Other groups in the city were playing White pop songs, but, “We didn’t want to touch that. We had a badge of honor.”

[Above excerpt from Carlos Santana: Love, Devotion, Surrender—The Illustrated Story of Santana’s Musical Journey. The book, published on May 27, 2025, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Listen: Unfortunately, there are no recordings available of Carlos Santana playing violin or of his teenage bands, but here’s a 1968 show at San Francico’s Avalon Ballroom that predates Santana’s debut album.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.