“That thing was like lightning in a bottle,” begins our Bobby Whitlock interview in 2015 of his short-lived band with Eric Clapton, Derek and the Dominos. “We did one club tour, we did one photo session, then we did a tour of a bit larger venues. Then we did one studio album in Miami. We did one American tour. Then we did one failed attempt at a second album.” And all within about a year’s time in 1970.

“That thing was like lightning in a bottle,” begins our Bobby Whitlock interview in 2015 of his short-lived band with Eric Clapton, Derek and the Dominos. “We did one club tour, we did one photo session, then we did a tour of a bit larger venues. Then we did one studio album in Miami. We did one American tour. Then we did one failed attempt at a second album.” And all within about a year’s time in 1970.

[Whitlock died on August 10, 2025. We’ve kept this interview as-is; thus many references remain in the present tense.]

So in this case, the oft-overused flash of lightning description is right on the money. And Whitlock was a key part of the kinetic energy behind what’s considered a genuine landmark in not just Clapton’s career but the entire classic rock genre: the 1970 album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, co-writing six of the double album’s 10 original songs (plus… read on), and bringing his soul-soaked Deep South keyboard skills to the musical mix, taking the vocal lead on two tracks and doubling/trading off with Clapton throughout the rest of the album.

Now, five decades later, he is the keeper of the Dominos legacy. And the dedicated survivor of a star-crossed band if there ever was one. Although today Clapton reigns as the major domo of 1960s rock guitar heroes alongside being a pop star, after the band’s short flash as a working act, he descended into some three years of heroin adduction and seclusion. Duane Allman, who played on most of Layla, was killed in a motorcycle crash on October 29, 1971. Bassist Carl Radle recorded and played with Clapton later in the ’70s and died of a kidney infection, exacerbated by his alcohol and drug abuse, in 1980 (see our On This Day item on him here). Drummer Jim Gordon as well continued to engage in substance abuse, damaging his career with behavioral issues. In 1983, he murdered his mother, claiming a voice in his head had told him to do so. He was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and remained incarcerated until his death on March 13, 2023.

Related: Our feature on Jim Gordon

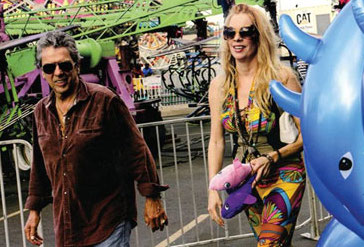

Although Whitlock, only 22 years old at the time, helped Clapton all but define anguished unrequited love in the most profound rock ‘n’ roll terms and tunes on songs like “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad,” “Tell the Truth” and “I Looked Away,” his own ultimate love story is something quite different, and a rather delightful one at that. Though his post-Domino years were not without their struggles, today he’s blissfully married and in musical partnership with singer, bassist, guitarist, sax player, songwriter, recording engineer and producer CoCo Carmel.

And the two are now taking the act they’ve honed over the last decade in the clubs of Austin, TX and the Dominos musical legacy on the road from time to time.

Growing Up Soul Deep

What dampened the lightning of the Dominos was “Everybody was doing entirely too much drugs and alcohol,” bemoans Whitlock, born on March 18, 1948. “And then Jimmy Gordon wanted everything that Eric had, he wanted to be a big superstar and wasn’t content and happy to be just the greatest drummer on the planet and in the very best band on the planet.”

Whitlock stresses that last point. “We were better than anybody.” One of the key elements that made them what he feels were the World’s Greatest Rock ‘n’ Roll Band for that all-too-brief time was Whitlock’s deep Southern musical soul. Growing up a preacher’s kid in a family poor as a church mouse, he was weaned on spiritual music (and did some cotton picking in his youth). Coming of age in Memphis, Whitlock was steeped in R&B in the city where white rock ‘n’ roll was born at Sun Studio.

By his teens Bobby was singing and playing Hammond B-3 organ around the region in his soul band The Counts, learning what really connects with an audience. He also started hanging around Stax Studio and was taken under the wings of the house band, Booker T. and the M.G.’s. He honed his organ skills watching Booker T. Jones play from over his shoulder. His first recording session “was [Issac] Hayes and [David] Porter” – then a Stax Records songwriting team – “and me doing handclaps on ‘I Thank You'” (Sam & Dave’s last Stax single and a 1968 #9 pop hit). “Everything had handclaps on it back then,” he notes.

“If you didn’t know ‘Midnight Hour’ or ‘Knock on Wood’ I didn’t wanna know about it.”

Whitlock was the first white act signed to Stax/Volt’s Hip label, but nothing came of it. “They didn’t have the same idea that I did about what I wanted to be,” he tells Best Classic Bands. “Stax was trying to get in on that English Invasion thing. They tried to develop me into that kind of artist, and that lasted about 15 seconds.” The next three years, however, launched him into a whirlwind within the rock music stratosphere and landed Whitlock amidst some top British Invasion stars.

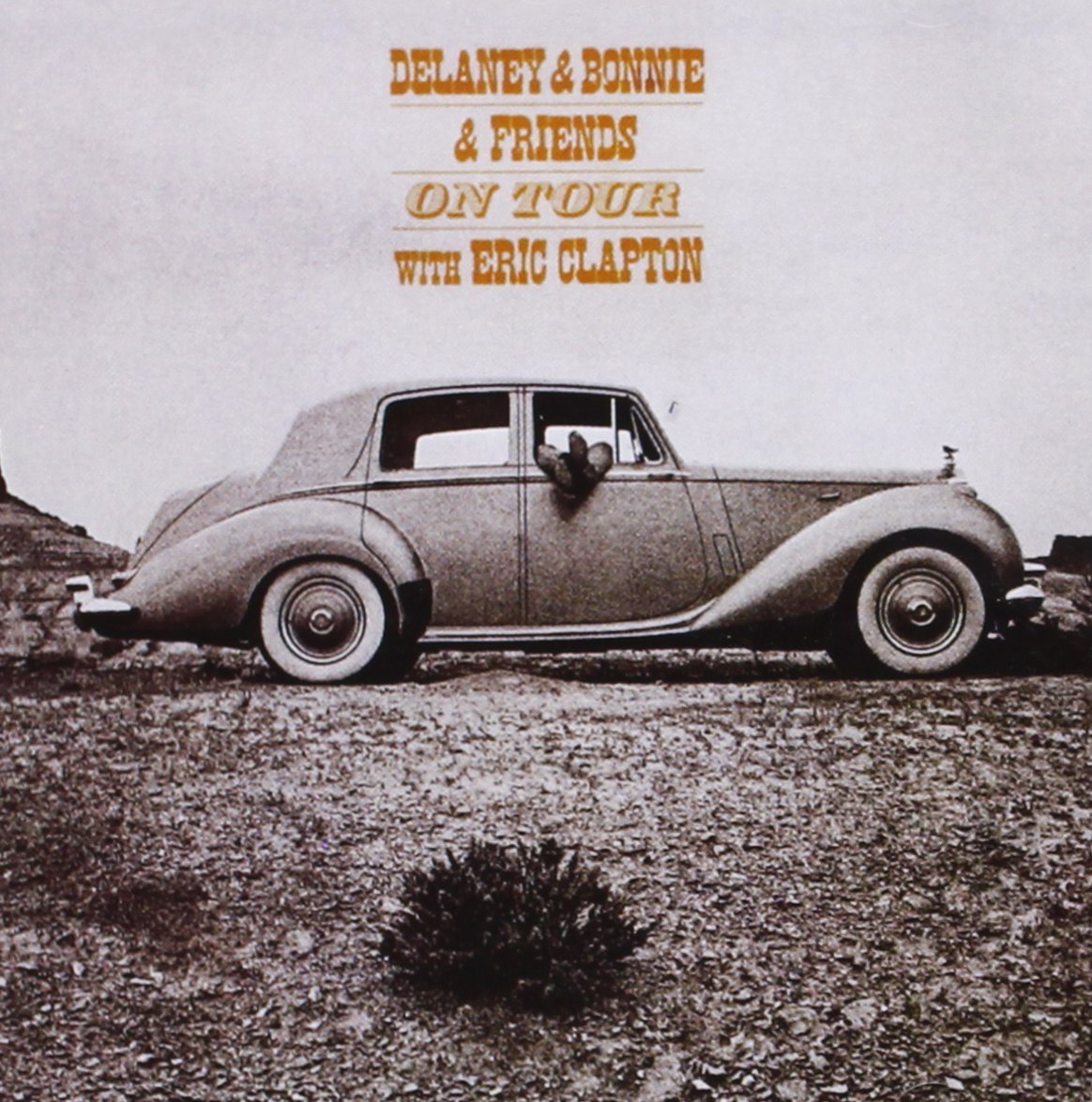

Working the Road with the Revue

Delaney & Bonnie came to Memphis to cut their first album, Home, at Stax, and afterwards Whitlock headed out to Los Angeles with them, becoming the first member of their “Friends” band, which came to include Radle and Gordon as well as other top players like drummer Jim Keltner, Leon Russell, horn players Bobby Keys, Jim Horn and King Curtis, both Gregg and Duane Allman at various points, singer Rita Coolidge and some English stars like Clapton, Harrison and Dave Mason. Nearly (and woefully) all but ignored today, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends at the juncture of the 1960s and ’70s were the most thrilling, red-hot rocking blue-eyed soul revue on the planet, tearing a page from the Ike & Tina Turner playbook and stamping it with their own imprint.

They so impressed Clapton that he took them on tour opening for Blind Faith. And when that short-lived supergroup broke up, he began playing with the group as just another member and had them play on his debut solo album. “That was a revolving door of musicians,” Whitlock explains of the band. Much as the music was awesome, “One thing with that band – nobody ever got fired. Everyone would quit… as soon as they could. I was the only one who waited until I couldn’t stand it any longer and then I quit.

“You can only take so much nonsense when people’s egos are running their lives,” he explains. “Being with them was an experience I wouldn’t ever want to do again. But it was great until the drugs and alcohol got involved.”

“You can only take so much nonsense when people’s egos are running their lives,” he explains. “Being with them was an experience I wouldn’t ever want to do again. But it was great until the drugs and alcohol got involved.”

On the other hand, “I learned more from Delaney Bramlett than I can ever possibly recount. If I need something I can go to the well and there it is,” Whitlock stresses.

After Bobby left D&B in 1970, Clapton then invited him to come stay at his English country manor and collaborate on songs. “I asked my mentor Steve Cropper if I should do it, and he was like, ‘yeah!'”

“We were hanging out and writing songs and not even thinking, like, hey, let’s put a rock band together and get so and so and so and so. Nobody was making any plans. It was all about right now.

“Then George called….”

All Things Must Rock

Whitlock, Clapton, Radle and Gordon became part of the core crew on the sessions for Harrison’s post-Beatles debut, All Things Must Pass. When Harrison had business elsewhere for a few days, he told the four to use the studio time with producer Phil Spector to cut some tracks, which yielded the debut Dominos 45, “Tell the Truth” b/w “Roll It Over.”

Related: Whitlock talks about the “missing” ATMP studio credits

Whitlock says of Clapton, “He wanted to be Derek not Eric. He wasn’t ready to step into his role of as a solo artist at that time.” The four musicians did a show at London’s Lyceum Theater, and then set off on a tour of small English venues as Derek & the Dominos where the admission was £1, and Clapton’s name was forbidden to be used in any advertising.

In late August of ’70, the Dominos arrived at Criteria Studios in Miami to record with producer Tom Dowd. He took them to see the Allman Brothers Band, Clapton and Duane Allman bonded, and the latter joined the Layla sessions to help create some of the most incendiary dual guitar rock ever recorded. The album was suffused with Clapton’s passionate longing for his best friend Harrison’s wife Pattie Boyd – interestingly, while in England Whitlock dated her sister Paula – and even though it was only a middling hit on its release, over time its stature grew to become considered a rock ‘n’ roll masterpiece.

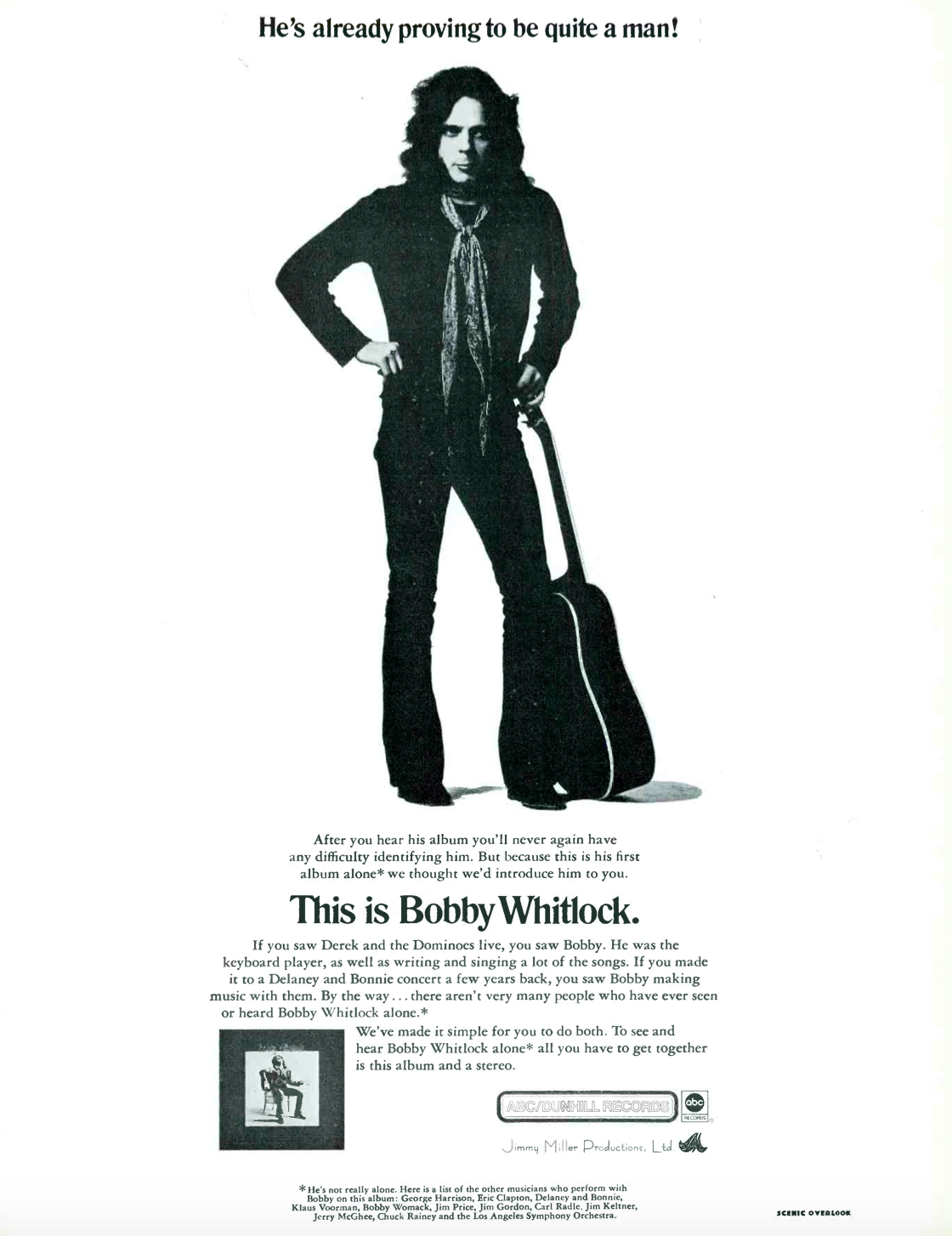

After the Dominos disbanded, Whitlock recorded a few solo albums in the 1970s that, good as they were, didn’t manage to launch a sustained career for him. With the rise of disco he became disinterested in where popular music was going and semi-retired to a remote country refuge in Mississippi with his wife to raise his kids. Whitlock built a home out of one old pole barn and a recording studio in another.

But his plans to keep making music got sidetracked. The demon was again drugs, as with the Dominos. But a different kind of drugs and dealer.

The Long Journey to Love

As one sits down for brunch with Bobby Whitlock and Coco Carmel, the impression given by the music they make together and the pictures in the packaging is only heightened – this is a couple who seem like they belong together, a complementary matched set.

“I think so because that’s why we’re together,” Carmel says.

“We were brought together by the universe,” Whitlock offers.

I ask how they met and their first impressions. “We kept crossing paths for the longest time,” CoCo notes. “First time we met was when I was with my ex, Delaney Bramlett,” who she was married to from 1987 to 2000. “And we went to Mississippi to see his aunt, who was not well. We decided to take his mother out there to see her.”

“I had a farm in Mississippi that was about 45 minutes away,” Bobby adds.

Whitlock and Carmel (Photo: Todd V Wolfson)

“He just kinda showed up and disappeared into a back room somewhere,” Carmel recalls. “So actually it was really no impression because I didn’t really see him. His impression is completely different.”

“I was captivated,” Whitlock confesses. “Delaney was my best friend. I was married and my wife was down the road at my farm. When I saw CoCo my heart just fell right to the floor. I couldn’t keep my eyes off her, which was understandable.”

Hmm…. In love with your best friend’s wife…. Where have we heard this song before?

“He looked very different than how he does now,” CoCo says. “He was very unhappy and it’s amazing how much different people can look when they’re unhappy.”

“I was,” agrees Bobby. “And I had to leave so I wouldn’t keep staring at her.”

“So he walked out,” CoCo notes. “Then we didn’t see each other for 10 years.”

“I had this beautiful studio, and I am two-and-a-half miles from my nearest neighbor, three miles up from a paved road,” Whitlock recalls. I was living back in the middle of a national forest, and cobwebs were in my studio and on my equipment. That was how dysfunctional I had become.”

The issue was the result of an inner ear condition that was causing vertigo that he had an operation to correct. Afterwards, the docs start laying on the pills. “Next thing you know I’m taking seven different meds and going crazy, and there was nothing wrong with me.

“That changed on October 13, 2000.”

The Road Back to Himself

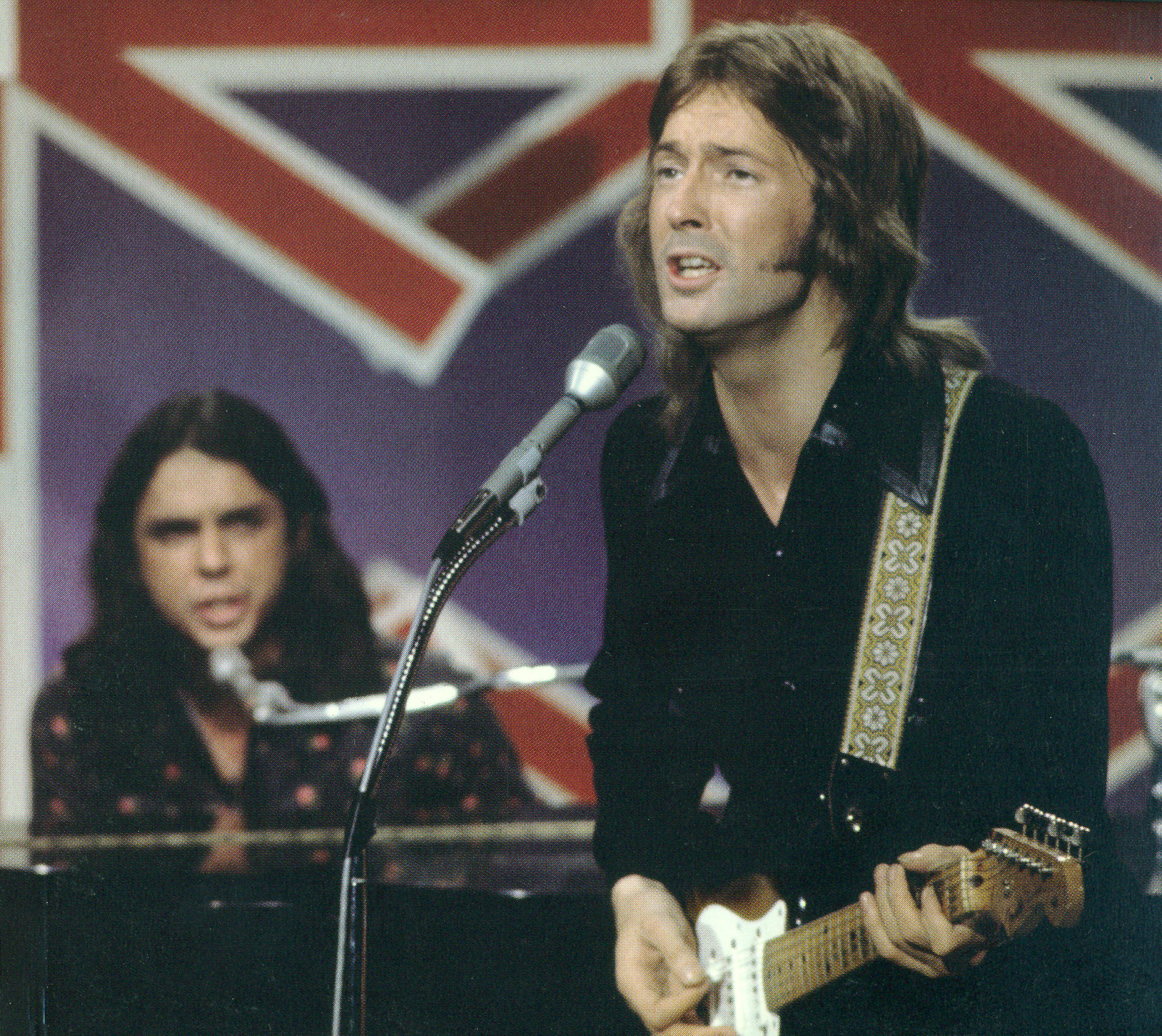

What began the process was a call earlier that year from Jools Holland, the former Squeeze keyboard player who has become English TV’s prime musical compere, first with hosting The Tube and then with his own Later… with Jools Holland music show. And a Whitlock fan who wanted him to appear on it.

“I did at first agree to do it,” Bobby explains. “But I did not even want to do that show. Then they called me back again. They didn’t know what condition I was in. They said, ‘Eric will do it with you if you agree to do it.’ I said, let me think about it. Eric had already agreed to change all of his schedule around to do it. And I was still saying no. I elected to do it anyway. I figured, I can make it though it.”

“I did at first agree to do it,” Bobby explains. “But I did not even want to do that show. Then they called me back again. They didn’t know what condition I was in. They said, ‘Eric will do it with you if you agree to do it.’ I said, let me think about it. Eric had already agreed to change all of his schedule around to do it. And I was still saying no. I elected to do it anyway. I figured, I can make it though it.”

Whitlock and Clapton hadn’t seen each other for some 30 years since the Dominos ended.

When he arrived at the London studio for rehearsal, “I looked across the room, and I walked in past Eric, He was sitting on top of his amp, as close to me as I am to you, and I didn’t even look at him, I didn’t recognize him. I was pointed towards going to my piano. I was on all those meds and still drinking wine. My whole insides were convulsing,” he relates.

“I then saw Eric sitting there across the room. He had his guitar on his lap and his legs were crossed and he was sitting on top of his amplifier. He had a sweatshirt on and a baseball cap. And there was a sense of peace about him, an aura of peace. And… I wanted that,” Whitlock says. “I knew that Bobby, the guy that is talking to you here now, is not shrouded with all these pharmaceuticals and alcohol. I remembered me while in the throes of all that. And I said, I want my life back. And pretty much six months afterwards to the day after I had that epiphany, I called it all off.”

The reconnection with Clapton had other positive effects. Whitlock had sold off the rights to his royalties from the Dominos to survive over the years, Clapton and his manager paid off Bobby’s debts and regained his ownership of his Layla assets for him.

Even better, “Eric finally after some 30 something years admitted that I did write ‘Bell Bottom Blues’ with him, and he did try to compensate me a little.”

There has also been co-writing royalties from the jams on the second disc of All Things Must Pass. “That’s been paying my electricity my whole life,” quips Whitlock.

Then there was another jam at Olympic Studios with the Rolling Stones one London night based around a Whitlock melody. The track wound up on Exile on Main Street. With a Jagger/Richards songwriting credit. And on which Richards was said to have played Whitlock’s piano part even though Bobby remembers that the Stones guitarist nodded out after he finally made it to the session. “I just shut the door on the Rolling Stones,” is all Whitlock says.

A Silent Yet Fullest Partner

As Bobby and I talk about his musical history, CoCo seems to enjoy it as much as I am, even if she’s by now heard the tales again and again. She briefly chimes in here and there to amend and lead the story along. And even if I know our readers are more interested in his time among the stars, I also want to know more about her, especially as Whitlock’s story also dominates even on their website, where there are precious little details about Carmel’s background.

“That’s fine with me,” CoCo says with a laugh. Then she slyly adds, “And it’s not polite to talk when eating.”

Born in San Diego, CA, Carmel had an itinerant life growing up due to her father’s career in the Navy. The bulk of her elementary school years were spent in Japan. A seminal musical memory is hearing Louis Armstrong sing “Wonderful World.”

“I always loved music,” she explains. “In junior high I just picked up all the instruments and there I went. By the time we moved to England [in her teens] I started playing professionally.”

What was she playing? “Funnily enough, Stax stuff, R&B, Tina Turner stuff,” says Carmel, who’s a good 20 years younger than her husband. She also became friends with Alexis Korner, the godfather of 1960s English blues rock, and masterful blues and boogie-woogie piano player Ian Stewart, original member of the Rolling Stones. “I don’t fit into any particular decade.”

Later, while living and playing in Los Angeles, Carmel met and married Delaney Bramlett, and under his tutelage became a skilled engineer and producer. Though Bramlett was known as a tough taskmaster as a bandleader, “He had his sweet moments,” Carmel says (he died in 2008). “He was a good teacher.”

This ad for a Whitlock solo album appeared in the April 8, 1972 issue of Record World

As Whitlock notes, “Delaney said she gets the best drum sound of anybody. Then Bonnie Bramlett says she gets the best vocal sound of anyone.”

Whitlock ponders how “We’ve led parallel lives and almost met many times. Finally we just collided.” They started out as close friends, then began making music together, and finally after many months became romantically involved.

About 10 years ago, the two were looking for somewhere to live and make music together. They considered Nashville but ultimately settled on Austin, drawn by the city’s tradition of being more about the music than the business. Bobby & CoCo soon had a weekly residency at The Saxon Pub, a longtime venue in South Austin favored by local artists and players for its top-notch sound and intimate, convivial atmosphere. They began recording albums together, the most recent of which, Carnival, was largely cut live at the Saxon and features them doing their renditions of songs from Layla alongside originals and their take on the gospel classic “John the Revelator.” Critics and fans began taking note that Whitlock was back in action, and how he and Carmel have revived the Dominos sound and spirit along with a Delaney & Bonnie vibe, albeit with their own take on it all.

Comfortably ensconced in a countryside hideaway on the eastern edge of the city, the two are homebodies that largely keep to themselves, focused on making music together. Then came a call from a booking agent, Robert Rowland (full disclosure: a friend and associate of this writer in New York City in the 1980s), who had been working with another classic rocker who also lived in Austin, the late Ian McLagan. Rowland offered to help Bobby and CoCo take their now well-honed act out on the road.

“I thought, this is something we can do,” says Whitlock, referring to their “Just Us” tour. “Just us, no roadies, no drivers, no nothing, just us.” They traveled in the cherry red SUV they call the “Bell Bottom Bluesmobile,” bought with the funds that came from Clapton’s settlement on that song. “It’s her birthday present.”

For fans it’s a chance to hear the Layla songs, “just like they were written, it was just me and Eric in a room with two guitars,” Whitlock says. “Eric hasn’t been doing them. Maybe one song in a show.”

Their appearances come with an extra added bonus on every stop. “We decided to get the premier guitar player in every city to play with us,” Bobby explains. “That way the music changes and evolves every night.”

They attribute the new boom in their career to “Deciding to let go of the reins and see where it leads us,” Whitlock notes.

As we finish up our meal Bobby hands me a domino tile – the symbol of his stature as the keeper of the Derek and the Dominos flame. Happy, deeply in love, and bursting with music much like he was almost a half century ago, it looks like his legacy is about to usher in a whole new phase in his long career. The initial ticket sales and media response to their upcoming shows augurs a successful run.

And Carmel is psyched to take their act they’ve honed in Austin to whole new audiences. “As someone said, it’s either going to be a total disaster or unbelievable. I have a feeling it will be unbelievable.”

The 50th anniversary editions of All Things Must Pass are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. Derek & the Dominos recordings are available here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

11 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationBobby Whitlock is an immensely talented and creative musician. He was early on, influenced and encouraged by many Stax records legends such as BookerT, Steve Cropper and Albert King. In turn, Whitlock influenced bandmate Eric Clapton and some other “notables”! And finally, what an incredible resume’. Fortune had the good sense to put Bobby Whitlock in the right places at the right times, but he would’ve shined like a diamond wherever he was! Thank you so much Bobby! From an obvious mega fan and neighbor in New Braunfels.

When I first heard Springsteen sing Born to Run I thought it was Bobby Whitlock. What a huge talent.

Many thanks, Rob, for your stimulating, incisive and informed article on Bobby Whitlock and Coco, a story that for many was largely unknown prior to its publication in BCB. Since the Saxon Pub gig ended, I lost touch with Bobby and was delighted to see that he’s still kicking it–just wish there would be a way to see him again. Years ago, he told me that he wouldn’t play outside Austin, and I hope he’ll reconsider in the future. The exposure you’ve given him may give rise to being able to see him play in other cities–he has more fans out here than he knows.

Thanks, too, for the excellent videos complementing your piece, especially the entire Delaney & Bonnie and Friends set which is a great piece of history, really a sort of rehearsal, predating and informing the terrific Mad Dogs and Englishmen rock’n’roll circus.

Best wishes,

Angus Wynne

Dallas

Two of the most-talented — and nicest — folks you’ll ever meet. Their A+ show has been a mainstay on the Austin music scene for years. Bobby & Coco deserve all the success life can bring to thenm.

I had to read almost the whole article to finally find a reference to Alexis Korner. I can’t understand why I can not find him PROPERLY mentioned in bestclassicbands, sad!

The Exile on Main St. track Whitlock is referring to is “Just Wanna See His Face”:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Just_Want_to_See_His_Face

The Wikipedia page for the album itself doesn’t mention Whitlock anywhere, something that probably needs addressing.