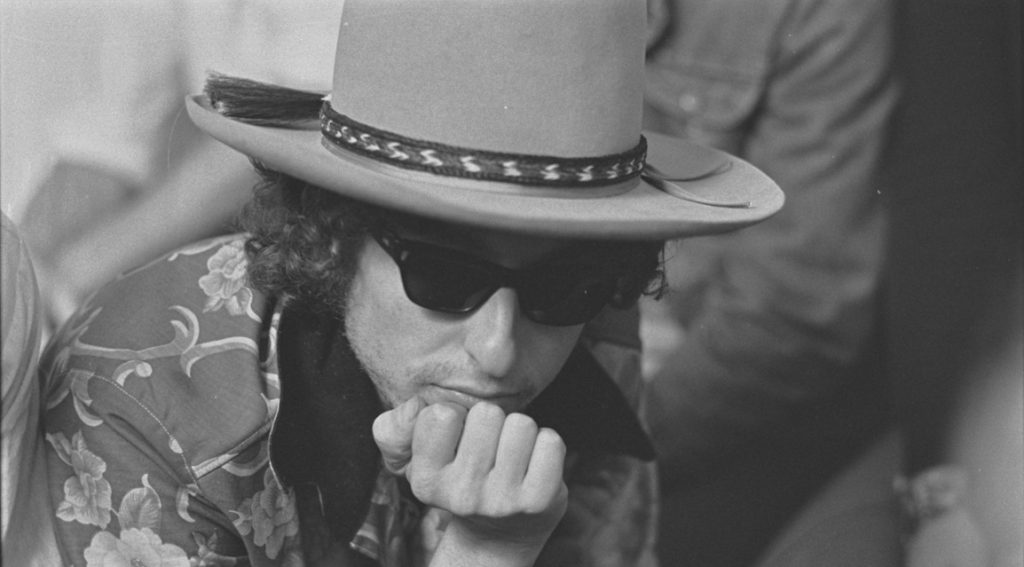

The Greenwich Village coffeehouse and music venue the Bitter End opened in 1961 at 147 Bleecker Street. Bob Dylan, who’d arrived in New York City in January of that year, spent a lot of time there playing pool, watching performers, doing shows himself when the spirit moved him and making friends and enemies. So when Dylan attended a Patti Smith show at the club on June 26, 1975, during the few years it was known as the Other End, he was in a familiar place and, it turned out, a receptive mood.

The Greenwich Village coffeehouse and music venue the Bitter End opened in 1961 at 147 Bleecker Street. Bob Dylan, who’d arrived in New York City in January of that year, spent a lot of time there playing pool, watching performers, doing shows himself when the spirit moved him and making friends and enemies. So when Dylan attended a Patti Smith show at the club on June 26, 1975, during the few years it was known as the Other End, he was in a familiar place and, it turned out, a receptive mood.

The idea of forming a new touring band, which would eventually be known as the Rolling Thunder Revue, flowed from watching Smith interact with her loose and adventuresome group. Acting quickly, enlisting his friend Bob Neuwirth to gather a basic backing band, by Oct. 30 Dylan was able to debut his new carnival-like concept in Plymouth, Mass. with Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Neuwirth listed on promotional posters and advertisements, just under his own name. Neuwirth called the core players “Guam,” thinking the name evoked a tropical paradise.

Over the life of the Revue, which lasted until December 8 on the first leg and from April 18 to May 25 during the spring 1976 trek of 22 shows, there were numerous (often unannounced) guests, including Joni Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot, Roger McGuinn, Kinky Friedman and Allen Ginsberg. “Guam” expanded and contracted according to Dylan’s musical needs and whims, but among the core musicians were Rob Stoner on bass, guitarists Steve Soles, T Bone Burnett and Mick Ronson, drummer Howie Wyeth, multi-instrumentalist David Mansfield, vocalist Ronee Blakley and, perhaps most crucially, violinist Scarlet Rivera.

In keeping with the surprising-but-true nature of much of what swirled around Dylan in 1975-76, he’d been tooling around Greenwich Village in the back of a limousine when he spotted the striking brunette Rivera walking down the sidewalk carrying a violin case. Pulling over, he talked to her a bit, and invited her to his rehearsal studio, where she spent the afternoon playing ad-hoc additions to some new songs he wanted to run through, several of which he’d recently co-written with the theatre director and songwriter Jacques Levy. “If I had crossed the street seconds earlier,” she later said, “it never would have happened.”

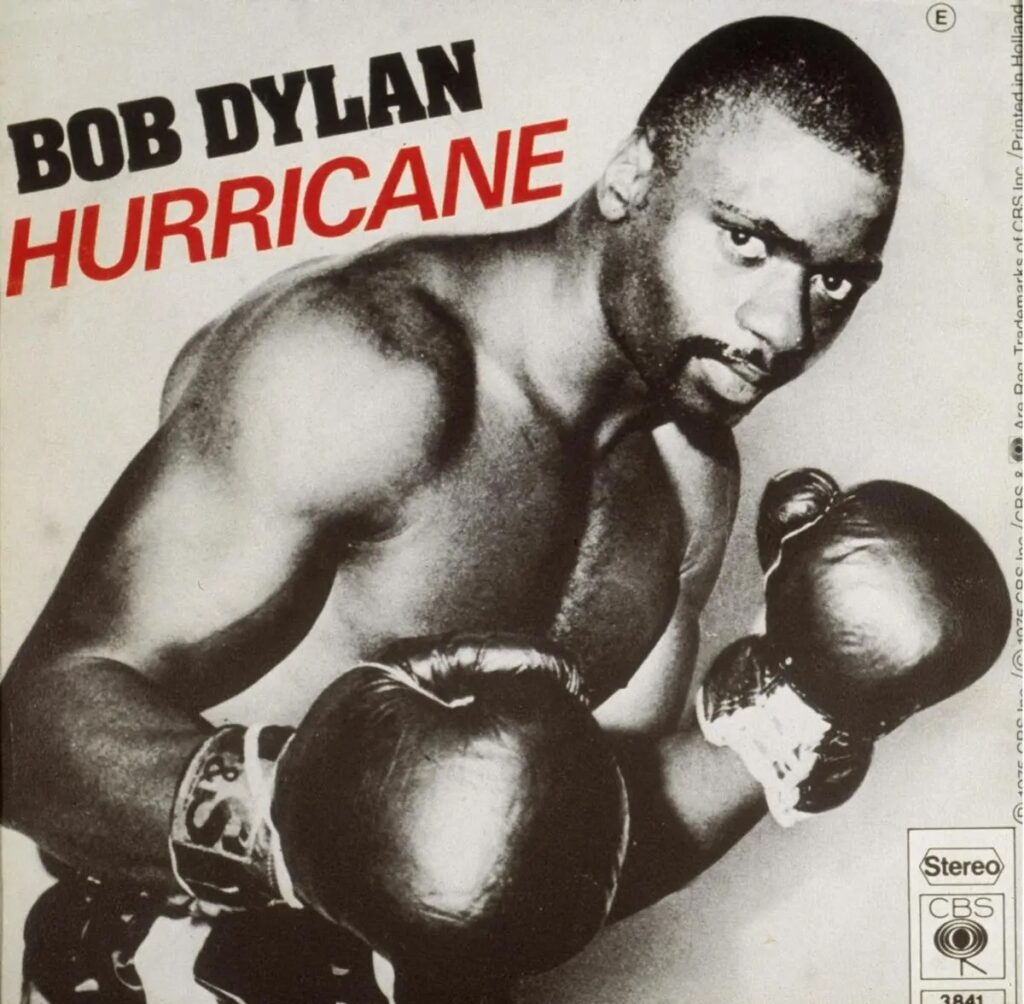

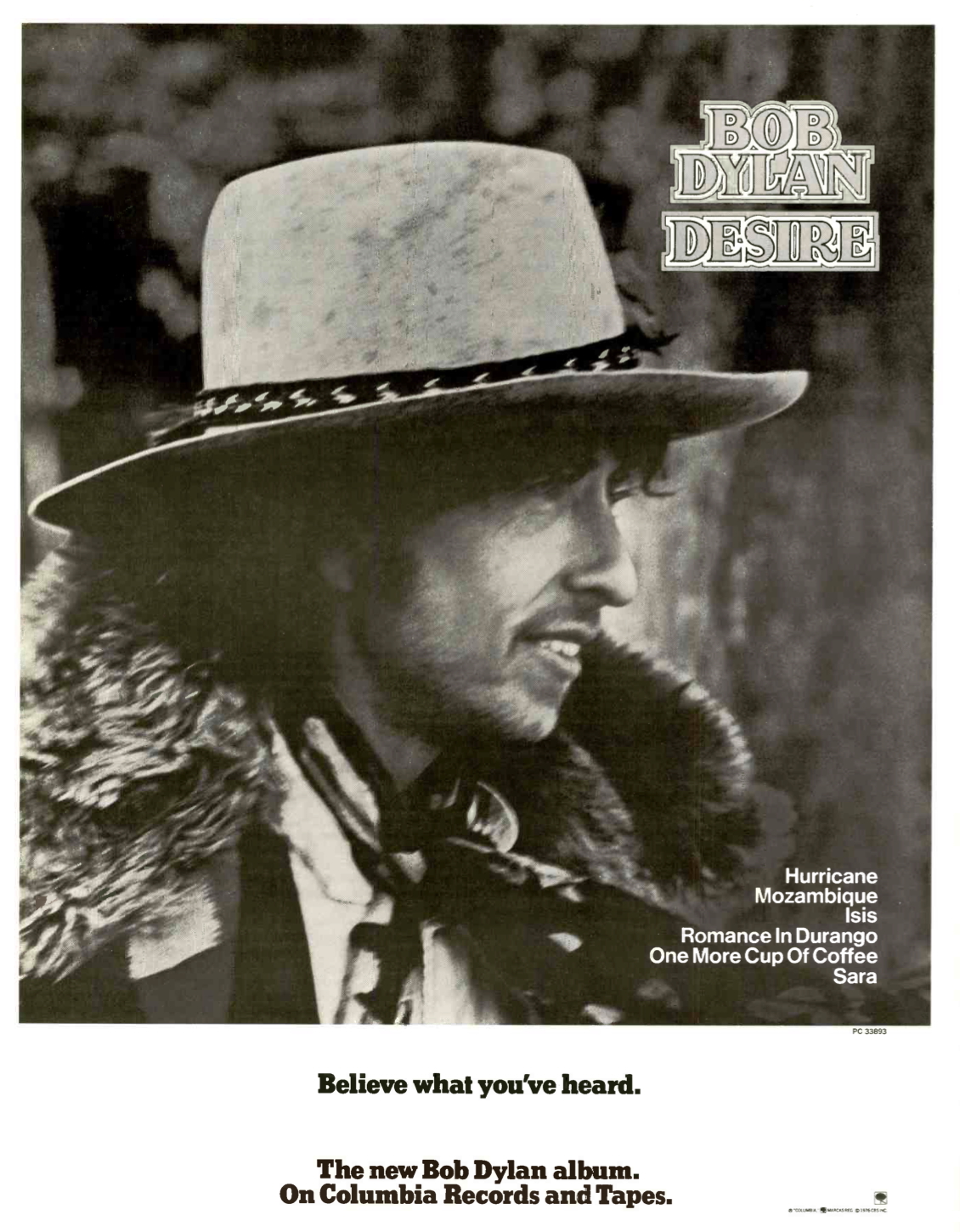

In between the two Rolling Thunder Revue tours, Dylan released his album Desire, the follow-up to his celebrated Blood on the Tracks. He’d begun recording with a July 14 session, which included various sessions musicians and members of Dave Mason’s band; it yielded nothing usable. Dylan and Levy took a break, secluding themselves in the Hamptons and eventually finished 14 songs. Those collaborations would be the subject of controversy and lawsuits for years afterward, both monetary disputes and finger-pointing about the historical details included in “Joey” (about the gangster Joey Gallo) and “Hurricane” (protesting boxer Rubin Carter’s triple-murder conviction).

Related: Our review of the Rolling Thunder Revue boxed set

A July 28 recording session, with nearly two dozen musicians available, revealed considerable conflicts between Dylan, who wanted to record mostly live, and the relatively inexperienced producer Don DeVito, who had other ideas. July 29 was a little better, with only a half dozen players on hand and one tune, “Oh, Sister,” worked up successfully.

Five of the nine songs on Desire were recorded July 30, with Stoner, Rivera, Wyeth and singer Emmylou Harris. Harris didn’t think she’d done her best work, and couldn’t make the July 31 session anyway, when “Isis,” “Sara” and “Abandoned Love” (eventually removed from the album in favor of “Joey”) were completed.

The lyrics to “Hurricane” were reportedly altered by Dylan during October 1975 re-recording sessions, at the insistence of Columbia Records’ lawyers, who worried that references to two witnesses in the case, Alfred Bello and Arthur Bradley, were defamatory. This new, somewhat faster version was subsequently issued as a two-part single, reaching #33 on the Billboard singles chart. Blakley and Soles sing harmony, Rob Rothstein (Stoner’s given name) plays bass, Luther Rix plays congas and Wyeth drums. (Track-by-track personnel listings for Desire have been disputed by Dylan scholars for decades: Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon’s 700-page All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track is one of many deep dives.)

“Hurricane” leads Desire, the lyrics cast in the present tense and treated not unlike a screenplay or live theatre script: “Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night/Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall/She sees the bartender in a pool of blood/Cries out, ‘My God, they killed them all.’” There’s no doubting the power of Dylan’s vocal, and the loose-limbed color of Rivera’s violin is truly remarkable.

“Hurricane” leads Desire, the lyrics cast in the present tense and treated not unlike a screenplay or live theatre script: “Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night/Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall/She sees the bartender in a pool of blood/Cries out, ‘My God, they killed them all.’” There’s no doubting the power of Dylan’s vocal, and the loose-limbed color of Rivera’s violin is truly remarkable.

Explaining how he worked with Levy, Dylan told Paul Zollo in 1991, “We both were pretty much lyricists. [We wrote] very panoramic songs because, you know, after one of my lines, one of his lines would come out. Writing with Jacques wasn’t difficult. It just didn’t stop.” For “Isis,” “It just seemed to take on a life of its own” without any conventional conception of how the Egyptian goddess of magic and healing might appear. Levy said Dylan originally conceived of the melody as a “slow dirge,” setting up the listener “for a long story.”

The final version, on which Dylan plays piano and harmonica, combines religion, wry humor and a pile of enigmas, with cascading verses and no chorus. After the narrator marries “the mystical child” Isis, he almost immediately takes off for a “wild unknown country.” But Isis remains a beacon: “I was thinking about turquoise, I was thinking about gold/I was thinking about diamonds and the world’s biggest necklace/As we rode through the canyons, through the devilish cold/I was thinking about Isis, how she thought I was so reckless.” Again, Rivera punctuates the simple chord structure with deft fills.

“Mozambique” is a weak three-minute trifle, which follows the complexity of “Isis” with cliched lyrics that Levy and Dylan must have tossed off quickly: “I like to spend some time in Mozambique/The sunny sky is aqua blue/And all the couples dancing cheek to cheek/It’s very nice to stay a week or two.” Dylan’s lead, Harris’ harmony vocal and Rivera are spot-on in a lost cause.

“One More Cup of Coffee” concludes side one of the original LP with strength. It was the first song Dylan wrote after completing Blood on the Tracks, before he started working with Levy. It was composed after visiting a ceremony during what he called “the gypsy high holy days” in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Merin in France, on his 34th birthday. According to Stoner, a run-through became the first take when he supplied impromptu bass lines when nobody else was quite ready for the song to start, as DeVito began rolling tape. Harris also reported the musicians had to be on their toes: “The band would start playing and [Dylan] would kind of poke me when he wanted me to jump in. Somehow I watched his mouth with one eye and the lyrics with the other.”

Dylan’s “One More Cup of Coffee” vocal is often cited as one of the few times he used a Hebrew cantillation style, but it could just as easily be thought of as Arabic or Spanish or, given the genesis of the tune, Romani. In the verses there are aphorisms (“Your loyalty is not to me but to the stars above,” “Your heart is like an ocean, mysterious and dark”) and some clumsy constructions (“He oversees his kingdom, so no stranger does intrude/His voice it trembles as he calls out for another plate of food”). The simple chorus lyrics, though, manage to pack a lot of the power into an anthemic melody: “One more cup of coffee for the road/One more cup of coffee ’fore I go/To the valley below.” Dylan has always been cagey about what “the valley” might represent, saying it “could mean anything.”

“Oh, Sister” is taken at a quite slow but effective pace; drummer Wyeth provides magnificent fills to keep it moving along, and Stoner and Rivera continue to be a crucial elements. Lyrically, it has implications beyond the family reconciliation theme, retaining some mystical images especially in the soaring bridge section: “We grew up together from the cradle to the grave/We died and were reborn and then mysteriously saved.” The Dylan/Harris co-vocal is the big draw here, providing some of the most beautiful moments on the LP. (Several accounts say the final take actually contains Harris’ vocal overdubbed July 30 over the tracks cut July 29.)

At 11:05 the longest cut on the album, the lyrically problematic “Joey” is next. Dylan loved singing it live, and told Zollo, “Not to blow my own horn, but to me the song is like a Homer ballad. Much more so than ‘A Hard Rain,’ which is a long song, too. But, to me, ‘Joey’ has a Homeric quality to it that you don’t hear every day. Especially in popular music.” Dylan liked the dynamism of the melody and the accumulated power at the climax, and gives one of his greatest vocal performances, full of nuance.

Wyeth supplies tympani-like percussion effects from his conventional kit and some added production echo, and Harris (often singing just behind the beat set by Dylan) and Rivera are invaluable once again. With the basic band augmented by Dominic Cortese’s accordion and mandolin and Vinnie Bell’s bouzouki, it justifies its epic length.

After years of criticism about glamorizing a murderous thug nicknamed “Crazy Joe,” Dylan appeared to distance himself from the lyrics he so brilliantly sang. In 2009, when journalist Bill Flanagan suggested the song “takes liberty with the truth,” Dylan responded, “I wouldn’t know. Jacques Levy wrote the words. Jacques had a theatrical mind and he wrote a lot of plays. So the song might have been theater of the mind. I just sang it.”

“Romance In Durango” is a child of Marty Robbins’ “El Paso,” but Dylan brings plenty of originality to it. The only Desire track from the July 28 recording session with a large band, you can hear Eric Clapton’s guitar and Mike Lawrence’s trumpet in the mix. The winning melody and exuberant vocals make for a terrific ride through colorful territory, complete with plot twists:

“Past the Aztec ruins and the ghosts of our people/Hoofbeats like castanets on stone/At night I dream of bells in the village steeple/Then I see the bloody face of Ramon/Was it me that shot him down in the cantina/Was it my hand that held the gun?/Come, let us fly, my Magdalena/The dogs are barking and what’s done is done.”

“Black Diamond Bay” was cut with trumpet and mandolin parts before being redone in simpler form. With a nod to Joseph Conrad’s novel Victory, Levy and Dylan describe various characters in a hotel (a Greek man, a soldier, a desk clerk, a gambler) going about their usual lives, unaware they are about to be killed in the eruption of the local volcano. The futility of it all seems to be the point: “As the island slowly sank/The loser finally broke the bank/In the gambling room/The dealer said it’s too late now/You can take your money/But I don’t know how/You’ll spend it in the tomb.”

The last verse focuses on a guy safe at home watching the TV news with a beer in his hand, indifferent to the suffering across the ocean he’s just heard about: “Seems like every time you turn around/There’s another hard-luck story that you’re gonna hear.”

The album concludes with the second tune written without Levy, a plea aimed squarely at Dylan’s wife, their long history together and current estrangement. Amazingly, Sara Dylan was in the studio on July 31, 1975, when Dylan cut the version heard on Desire. According to author Larry Sloman, Dylan turned to Sara, who was sitting behind glass in the control room, and said, “This one’s for you,” and she heard it for the first time. (After more reconciliations and break-ups, Sara filed for divorce in 1977.)

“Sara” starts with a mournful instrumental verse and chorus from Dylan’s harmonica, and is full of pain and nostalgia. After recalling time with their children on the beach, he gets to a chorus in which he admits he both admires and fails to understand: “So easy to look at, so hard to define.” The melody chosen for the chorus could fit a sea shanty or drinking song, but here it’s used to elevate her repeated name, calling her over and over.

Dylan moves back to the idyllic beach for a verse, and then again in the choruses, descriptions assert Sara’s magic character, calling her a “radiant jewel, mystical wife,” “Sphinx in a calico dress” and “glamorous nymph with an arrow and bow.” By the last line, he’s baldly begging, “Don’t ever leave me, don’t ever go.”

Desire, released January 5, 1976, hit #1 on the Billboard album chart. The songs continued to be heavily featured in the Rolling Thunder Revue live performances, and footage of several tunes made it into Dylan’s fantastical four-hour film Renaldo and Clara and the one-hour NBC-TV concert film Hard Rain, broadcast in September 1976. A 14-CD boxed set, The 1975 Live Recordings, was released in 2019 [available here] to coincide with Martin Scorsese’s documentary Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story. Dylan, ever the trickster, used the documentary to tell some outrageous lies about the tour, inventing characters and situations, creating another alternate history for Dylanologists to interpret forever.

Watch Dylan perform “Hurricane” live in 1975

Desire is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversation“Mozambique” is not a throwaway song. It’s actually one of the better songs on the album. It’s got a great rhythm/beat to it. I think if you ask most people, they will agree. It’s a lot better than you’re giving it credit for. Sure,the lyrics are simple. So what, it’s the sound of the song that’s flat out pleasurable. “Hurricane” is obviously the best song on the album. They really nailed it, but I love “Black Diamond Bay,” especially the line about sitting around watching old Cronkite grabbing another beer and another hard luck story you’re gonna hear and there’s really nothing anyone can say… and it’s so much more enjoyable an album than Blood on the Tracks, which overall is somewhat depressing except for “Tangled Up in Blue.”

Dylan redeemed himself with Blood and Desire and Planet Waves, although it ticked off Columbia records. Hurricane, while the popular song, is the only track I’ll skip when playing this record. All the other tracks on those 3 albums are classic.