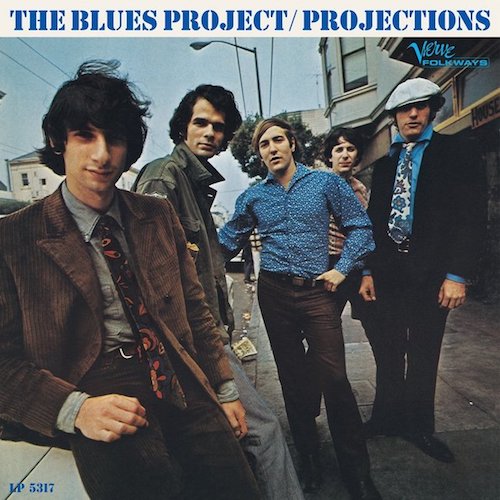

The Blues Project in 1966 (l. to r.): Andy Kulberg, Al Kooper, Danny Kalb, Steve Katz, Roy Blumenfeld.

They called themselves The Blues Project but, in the spirit of the times—the mid-’60s—the blues was only their starting point. Like Cream, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and many other outfits of that era, the New York-based quintet, although they certainly shared a passion for blues music, continually looked to expand in several other directions. On their second album, Projections—the only studio recording with their classic lineup—they did.

They formed in 1965 around guitarist Danny Kalb, bassist Andy Kulberg, guitarist/singer Steve Katz, drummer Roy Blumenfeld and, soon after, singer Tommy Flanders. The band’s name was borrowed from an Elektra Records compilation album, The Blues Project, to which Kalb had contributed two songs the previous year. With the addition of keyboardist and vocalist Al Kooper, whose profile on the New York scene had risen considerably after he slyly found his way to the organ bench for Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” sessions, the Blues Project signed with Verve/Folkways Records, which released Live at the Cafe Au Go Go in March 1966.

That album, recorded the previous November at the popular New York club, validated the band’s name, filled almost entirely with covers of songs written by the likes of Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf and Chuck Berry, as well as a couple of pop tunes, Donovan’s “Catch the Wind” and folkie Eric Andersen’s “Violets of Dawn.” Although the band packed in as much soloing and jamming as it could, little about this maiden effort suggested that the Blues Project, virtuosic as they were, had the goods to expand beyond their first love.

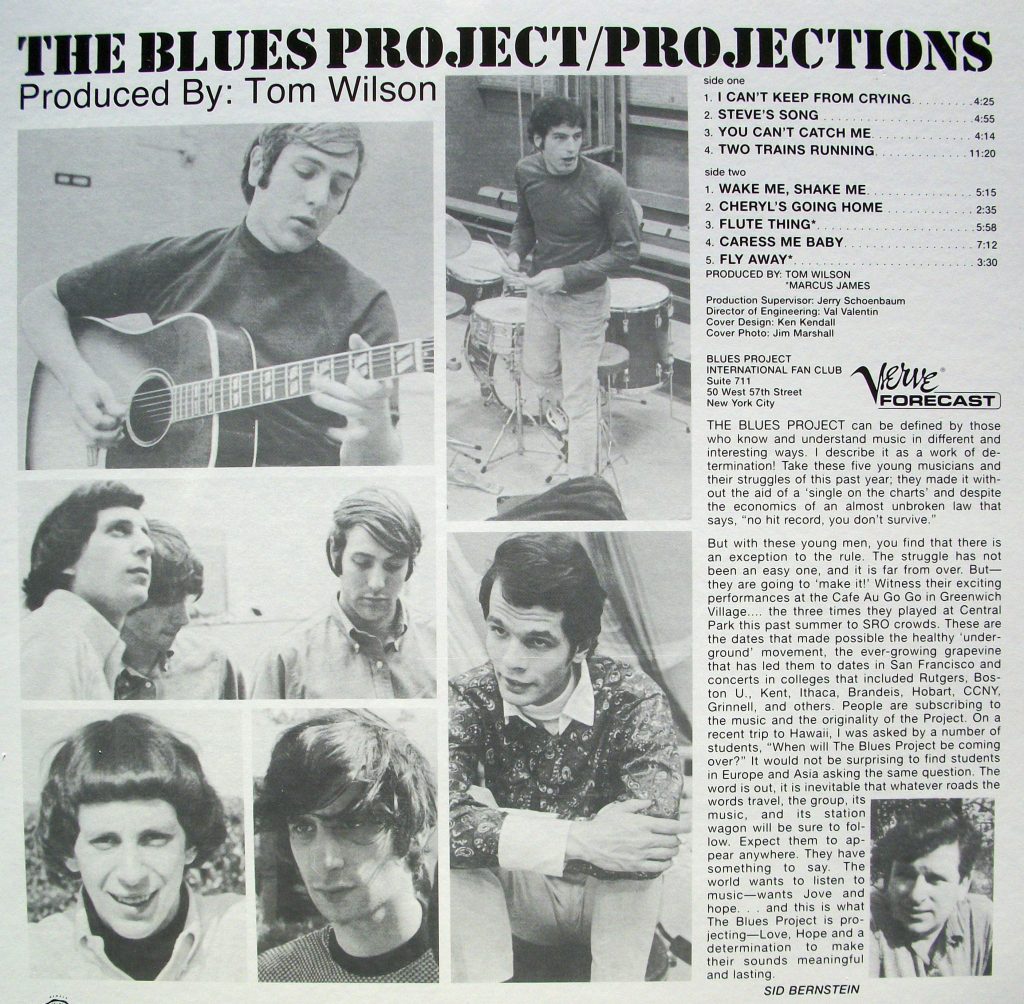

That was soon to change. By the time the debut hit the record shops, Flanders had already left the group and the Blues Project had moved beyond the blues. With Tom Wilson—having previously produced Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, the Velvet Underground, the Mothers of Invention and more—producing seven of its nine tracks, the quintet entered the studio to begin assembling their sophomore album. (The other two tracks, “Flute Thing” and “Fly Away,” were produced by Columbia Records’ publicist Billy James, although they’re credited on the album to Marcus James, his son.) It was released in November 1966.

In just a year the Blues Project had developed into a formidable and creative exploratory force, incorporating elements of other genres ranging from folk to jazz and tossing it all into a psychedelic blender. Although the track list this time around was still tilted toward cover material, both Kooper and Katz also contributed songs, suggesting that they were not such purists that they were restricted to updating the works of the Chicago and Delta masters.

Depending which version of the album you bought, the lead track was called either “I Can’t Keep from Cryin’ Sometimes” or simply “I Can’t Keep from Crying,” and was arranged by Kooper from the original Blind Willie Johnson version, which the bluesman called “Lord I Just Can’t Keep from Crying.” Kooper had previously recorded a solo version of the tune for a compilation album called What’s Shakin’, but the BP’s recording reimagined it from the ground up, opening with a jolting electric splash that gave immediate notice to those expecting more straight blues: be prepared to have your mind blown. Moving along at a propulsive clip, the band’s arrangement, from the first notes, allowed plenty of space for all five musicians to shape the direction of the track, which builds to a screaming crescendo, then lets up to catch its breath before Kalb unleashes a barrage of notes to bring it all back around to where it began.

Listen to “I Can’t Keep from Crying”

Steve Katz’s sole writing contribution to the album, “Steve’s Song,” is a much-needed reprieve after the relentlessly driving opener. A quasi-baroque acoustic guitar and flute (played by Kulberg) lead-in gives way to a folk-rock ballad sung by Katz plaintively. The title, Katz has said, came about when a record company executive called the band’s manager to ask the title of the tune, which had not been noted on the submitted paperwork. “Oh, that’s Steve song,” the manager replied, and that was good enough for Verve-Folkways. Had they bothered to ask Katz, he would’ve told them he planned to call it “September Fifth.”

Watch the Blues Project perform “Steve’s Song” live in 1967

A revved-up take on Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me” showcased Kalb on vocals and, of course, lead guitar, and gave way to the album’s longest track, an 11-and-a-half-minute, funereally paced reconstruction of Muddy Waters’ “Two Trains Running.” Kalb again shines here—he was in his element on this sort of unmolested blues—and the guitarist even makes the best of a bum note, using it to spontaneously lead the jam into another direction.

Side two of the original vinyl kicked off much the way that side one had, with a galloping raver of a rocker. “Wake Me, Shake Me” (not to be confused with the Four Tops’ “Shake Me, Wake Me”) had its roots in a gospel number that Kooper had heard in a New York club. Rearranged to fit the band’s style, it throbbed fiercely, with Kooper giving his most impassioned vocal performance of the album as the others turned in some of the most lysergic instrumental work of the Blues Project’s canon.

Listen to “Wake Me, Shake Me”

A spirited cover of folk-rocker Bob Lind’s captivating “Cheryl’s Going Home” follows, paving the way toward “Flute Thing,” considered by many to be the album’s tour-de-force performance. Composed by Kooper on acoustic guitar, inspired by a jazz guitar riff he’d heard, it was the least bluesy track on the album. Kooper plays an early electronic keyboard called the Ondioline (but which the BP dubbed the Kooperfone) and the flute that dominates the track comes courtesy of Kulberg, moving over from his usual bass duties. In concert, the piece was extended and used as a basis for additional sonic explorations.

Listen to “Flute Thing”

Another extended slow blues, Jimmy Reed’s “Caress Me Baby,” follows, giving Kalb another spotlight moment, before Projections winds up with “Fly Away,” a pleasant enough, if unessential, Kooper midtempo folk-rocker about the dissolution of his first marriage.

Considering it was recorded in three days with little preparation, Projections, with a cover pic by famed rock photographer Jim Marshall and liner notes by the band’s new manager, (Beatles concert promoter) Sid Bernstein, who called the album “a work of determination,” did OK, reaching #52 on the Billboard LP chart after its November 1966 release. (Oddly, the original LP cover does not mention the band members’ names anywhere.)

In retrospect, Kooper has said, it might have been a better recording had the band and producer had more time to work with it. Nevertheless, it received substantial airplay on the newly emerging FM rock stations and brought renown to the five key members.

Their lifespan as a band was already sputtering toward a finale by the time Projections was released though. A third album featuring the classic lineup, Live at Town Hall (actually recorded at Stony Brook University and doctored in the studio), furthered their stance among cognoscenti of the hip. The band was booked to play the infamous Murray the K-hosted April 1967 run of shows at the long-defunct RKO 58th Street Theater in New York—where both Cream and the Who played their first American gigs—but the Blues Project were done by the end of spring, due largely to antagonism between Kalb and Kooper. In June, the BP played the Monterey Pop Festival without Kooper (who played his own impromptu set there and served as stage manager), and shortly thereafter he and Katz went on to form Blood, Sweat and Tears, with which they would record their phenomenal debut album, Child Is Father to the Man before moving on again.

The Blues Project continued for a while with a few member shifts, releasing a trio of albums without Kooper before the classic quintet reunited for a Central Park concert in 1973 that also became a live album. Sadly, the band is not well known today among younger rock fans, but many who were around at the time still cherish their small but potent output, particularly the one studio set that encapsulated everything that made the Blues Project a great ’60s band.

Some of their recordings are available here.

Bonus video: Watch the Blues Project, post-Kooper, play “Flute Thing” live

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationIt’s astounding that, after boosting the careers of so many performers from Bobby Darin to Dionne Warwick, Bobby Vinton, The Lovin’ Spoonful, The Who, and even Al Sapienza (of “The Sopranos” fame), Murray the K and his unique “Music in the Fifth Dimension” show at the RKO 58th St. Theater get labeled as “infamous.” The mix of talent on that bill was a black and white blend of rock, folk rock, and R&B that marked the last stand of theater-based rock ‘n’ roll shows before stadiums became the venue of choice for everyone from the Stones to Cher. In the ’60s, the only multi-act events that topped Murray’s shows were Monterey Pop and Woodstock… and they were both outdoors. If you’re looking for a show that was infamous, Altamont takes that prize.

Dakota Recollections is my favorite by this line up.

“Dakota Recollections” WASN’T by this line-up, though. That version of the BP had only Blumenfeld and Kulberg left over, along with three new players. The band then morphed into Sea Train (or Seatrain, take your pick).

That is correct but there is no mention of this song in the article.

Growing up in New Jersey, Projections was a must have record for your collection! Live at Town Hall is fun. The version of Two Trains Running on Al Kooper’s Soul of a Man has the spirit and vibe of the original Blues Project!!