‘Yellow Submarine’ Before It Was ‘Yellow Submarine’— A Naked Submersible, Sung By John Lennon

by Colin Fleming The Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” is what I used to think of as a back-pocket song when I was first getting into the band. I had fallen in love, hooked and smitten in the ways of love. You fall, and then you choose to fall further, to let yourself go, and it’s the same—in that one regard, anyway—if we’re talking a person or a band.

The Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” is what I used to think of as a back-pocket song when I was first getting into the band. I had fallen in love, hooked and smitten in the ways of love. You fall, and then you choose to fall further, to let yourself go, and it’s the same—in that one regard, anyway—if we’re talking a person or a band.

I knew “Yellow Submarine” before I loved the Beatles, because who didn’t? The song was joyous, mellifluous, playful, whimsical. You encountered it in sing-alongs in grade school, at summer camp, cookouts. It defined a form of smart fun, the sort that’s perfect for children and their limpid ways, without the hard edge of rock and roll’s brand of fun.

“Yellow Submarine” suited adults as well, because it was one of those works born of the imaginative places of childhood that encourages adults to get in touch with their own inner child, that bounding representative of playfulness who dwells in everyone, however deep down.

From an early age, I thought of “Yellow Submarine” the way I did Charlotte’s Web, Peter Pan and the Peanuts gang. I knew it would be there, and it was easy to love, and I went exploring.

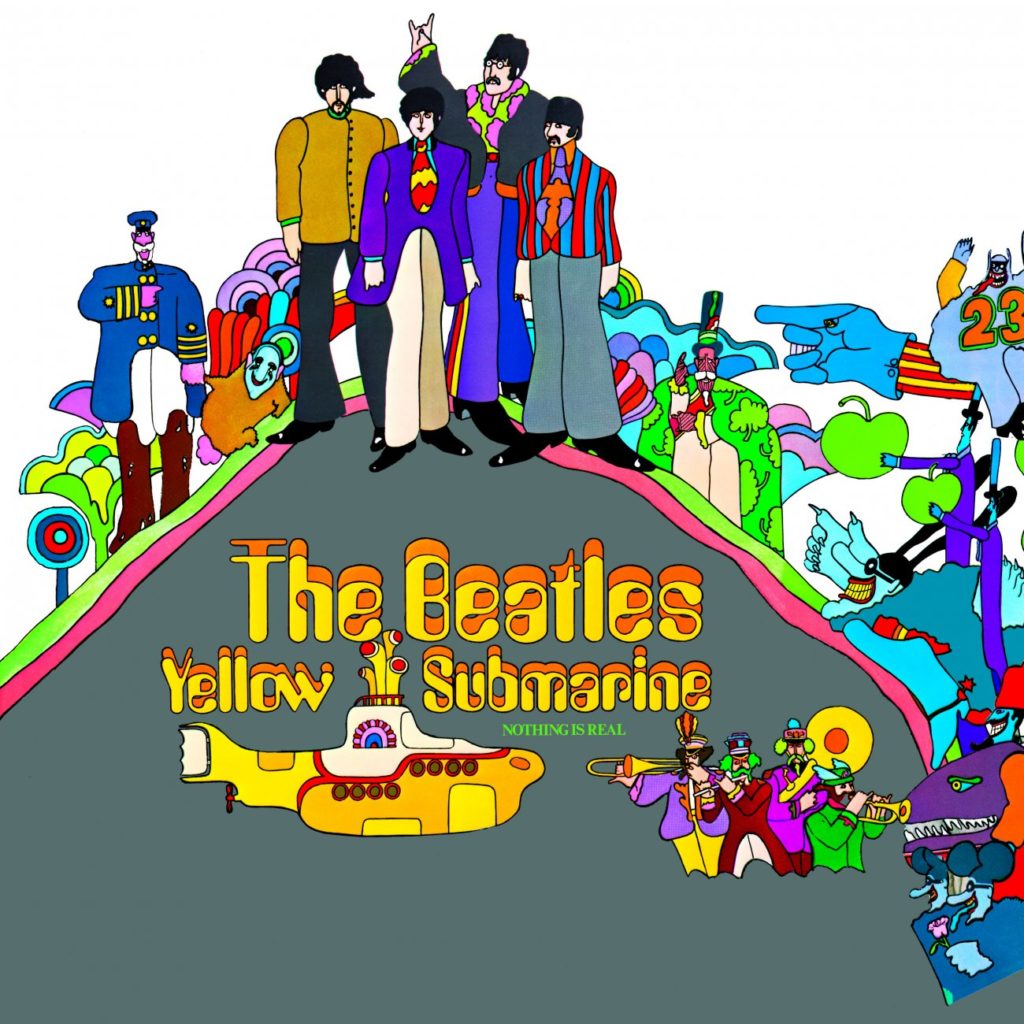

That meant that I soon came to the Revolver LP, and I discovered the sharp-tongued snarl of “Taxman,” the airy classicism of “For No One,” the nightmare, end-of-the-world/start-of-a-new-one vistas of “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

As I got older, I could see how Revolver, in its range of styles, was essentially the Beatles’ single-disc version of the White Album’s double LP bonanza. “Yellow Submarine” had much to do with that. It was a novelty number that was also too well-done and clever to be an actual novelty, the same as it was a children’s song that also suited adults.

The Beatles have these departure songs, where they move past even the regular extremes of range that help define them. The range is formidable, its representative contours and endpoints surprising in how far afield they are from each other. Certain songs, though, exist outside of the range because it’s hard to square them with the Beatles’ eclecticism. They are apparent one-offs that work, without smacking of gimmick or forced effort.

The Beatles have these departure songs, where they move past even the regular extremes of range that help define them. The range is formidable, its representative contours and endpoints surprising in how far afield they are from each other. Certain songs, though, exist outside of the range because it’s hard to square them with the Beatles’ eclecticism. They are apparent one-offs that work, without smacking of gimmick or forced effort.

Not that “A Day in the Life” was repeatable or ought to have been repeated, but you almost expect it more than you do “Good Night,” a John Lennon lullaby sung by Ringo Starr, that ends, of all things, the White Album. Nor do you expect “When I’m Sixty-Four.” It’s as if the Beatles elected to try something, just once, to show that they could do it, or satisfy a long-held urge to do a song in a particular style.

One imagines John Lennon or Paul McCartney listening to the radio as kids, hearing a different strain of music, and thinking, “I’d like to do one like that someday,” then going on to do it. Or else doing a piece of music based upon an old air of a bygone era and style that their mother used to love.

It’s always pleased me that John Lennon wrote “Good Night,” because it doesn’t seem like he would have, unless you really know him as much as one can without personally knowing someone.

But then again, nothing makes everything known to us like art, even when it isn’t biographical in nature. Art has a way of fostering surprises, and also making the seemingly impossible very possible indeed, because it opens other worlds within our overarching one. I’ve always wished I could hear Lennon singing “Good Night.” There was a recording of exactly that, and McCartney swore it was one of the most beautiful things he had ever heard. I trust both the idea and the messenger.

For a long time, we’ve thought that McCartney was most responsible for “Yellow Submarine.” Starr needed his vocal set-piece for the record, McCartney went to work, with assistance from Lennon, and a key line worthy of the lilting, imagistic grace of Yeats—“Sky of blue and sea of green”—was provided by Donovan. According to the history books and assorted recollections, the song more or less grew up then and there, on the spot, probably like McCartney’s “Get Back,” as we saw in the eponymous docu-series.

The song does seem like such a McCartney thing to do. He’d be your guy for whimsy and melody. We think of him as doing out-and-out fun better than Lennon. The latter was about wit and edge, not wholesomeness.

Starr made a remark at the time that the duo was finding a song for him to sing, but if that didn’t come to fruition, he’d have to run down a country and western number from someone else’s record and cover that.

Can you even imagine? Starr singing a Carl Perkins or Hank Williams number on Revolver nestled between “Here, There and Everywhere” and “She Said She Said”? Incongruity overload.

The mind boggles, but then again, it also does when we hear “Long Tall Sally” still being performed in August 1966 on tour. The Beatles were musical time travelers, but the point of time traveling is to be in one place at one time, not with a dangling foot left behind in a period the rest of you has already departed.

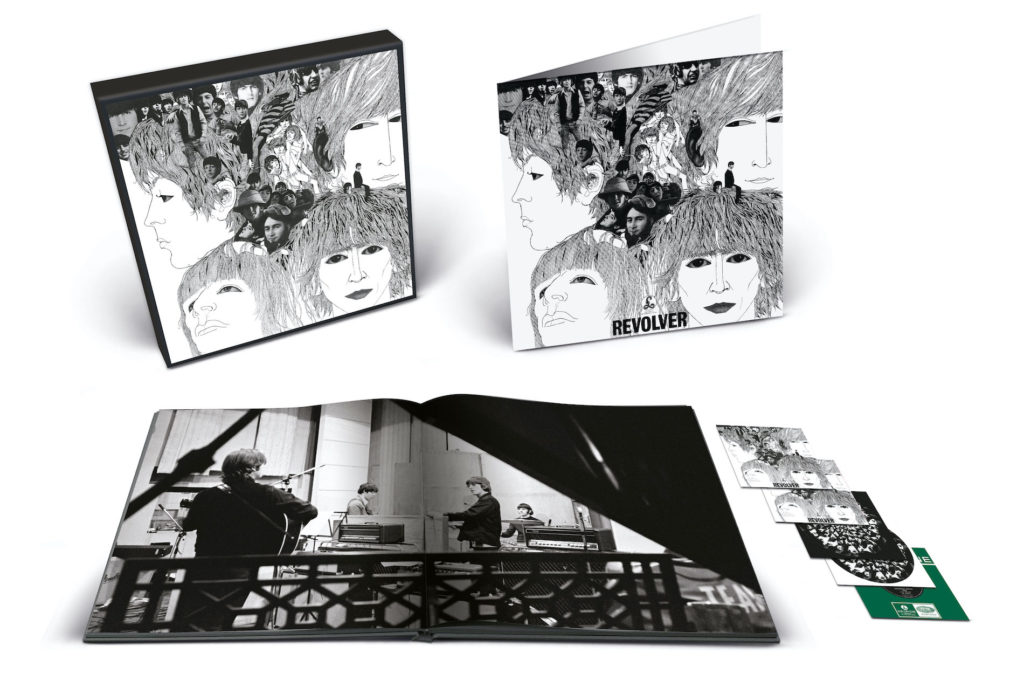

Everything is now different for “Yellow Submarine,” or at least insofar as the shipyard in which it was built, on account of the 2022 Revolver boxed set. There have been surprises that have rocked every last fiber in me, in terms of unreleased Beatles music, much of which I discovered on bootlegs over the years. The first take of “Strawberry Fields Forever,” for instance. First take of “A Day in the Life.” The country and western version of “Can’t Buy Me Love.” George Harrison’s acoustic version of “While My Guitar Gently Sleeps.” The unadorned sixth take of “Across the Universe” is one of the best things the Beatles—or John Lennon—ever made, and they didn’t even release it until it was big boxed set round-up time.

We must now add Lennon’s demo for “Yellow Submarine.” Unlike with, say, that first take of “A Day in the Life”—the recording I wanted to hear more than any other in my own life—I had no idea that this piece of music existed, let alone that it portended what it does.

Listen to John Lennon’s songwriting demo for “Yellow Submarine”

Or did. I don’t even know what tense we ought to be using. I do know that we can give the idea that McCartney wrote “Yellow Submarine” a suitable rest, or even dash it to pieces. He normally gets credited with the melody, but the demo on the Revolver box set shows that Lennon already had it. Here, it’s more elegiac, suggestive of Elgar, whom I bet Lennon heard a lot of, without trying to, growing up where he did, when he did.

We never really know, do we? That’s why I’ve never been much invested in books that are factoid-driven. Mark Lewisohn, for instance, is not for me. I never regard all of those facts as completely correct. Or many of them. I think that they may contain aspects of the truth, but they’re not adequate enough in and of themselves for me to be all that invested in their value. Patterns emerge, and you go with the pattern, rather than the one reported item. You piece matters together. You deduce. But the art is always so much more interesting anyway.

The official version of “Yellow Submarine” does have another Lennon quality—namely, narrative, with a guide to lead. Lennon the artist was the guide who shepherded us to other worlds. “In My Life” is another world. The same can be said of “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “I Am the Walrus,” “Tomorrow Never Knows,” “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),” “Come Together.”

We go places with Lennon that we wouldn’t go on our own. His songs excel at holding open doors that we didn’t know existed even as closed doors. We then pass through those entries, and what do we find? New worlds, yes, but also insights into us and our world. The world of who we are. I don’t mean political parties and wars and what has a tendency to trend. All of that flakes away; we are the real constants.

The titular submarine definitely journeys through worlds of imagination, which was used to further effect—a powerfully visual one—during the Yellow Submarine film, a masterpiece itself of conjoined whimsy and melancholia. A rare blend. It’s very Peanuts-y, actually. I think Linus would be enchanted by this side of the Beatles, as was I, with the song in my back pocket.

I don’t think I’m overstating anything in saying that of all the unreleased Beatles music I have heard, nothing has surprised me more than what is billed as the songwriting work tape of “Yellow Submarine” on the Revolver box. It’s just Lennon, the same as when he began working on “Strawberry Fields Forever” talking to himself (“I can’t do it…”) at what I presume was some deep hour of the night. Lennon excelled at opening lines, “Strawberry Fields” being a prime example. “Let me take you down” seizes us. It takes us. We’re off.

The official version of “Yellow Submarine” starts with the words, “In the town where I was born.” On the songwriting tape, Lennon instead sings, “In the place where I was born, no one cared,” and immediately we think, “What is happening here?”

The official version of “Yellow Submarine” starts with the words, “In the town where I was born.” On the songwriting tape, Lennon instead sings, “In the place where I was born, no one cared,” and immediately we think, “What is happening here?”

The suggestion is that no one cared from the precise moment of birth, of entry in this world, of the submarine surfacing, in a way. This was a man whose mother gave him up without really giving him up. Lennon was essentially both adopted and not adopted. He regularly saw a person—until her tragic, premature death—who ought to have loved him more than anyone else, who didn’t want to raise and live with him.

That is one cluster, as they say. But we should also never make a song chiefly biographical, which strikes me as disrespectful to what the song is. The best art is autonomous, or deserves to be looked at as such. If we can look at a work of art and say it improves based upon biographical details, then the art has failed. It wasn’t good enough on its own to be self-sufficient.

I would never say that about this song fragment that runs to just a little over a minute. You could have put it on Plastic One Band, the 1970 Lennon release that I regard as the only out-and-out full-on work of art that any of the Beatles made in their solo careers.

Lennon repeats the “no one cared” line, and his voice breaks. I’ve heard Lennon sing with a cold (check out the outtakes to Please Please Me) and warble off-key in fetching fashion (the early, guide vocal stab at “Yes It Is”), but nothing like this. The singer is barely getting through his own fragment of a song. He’s gone in, and he’s going under, a submersible unto himself. The waters have him.

Yoko Ono would later provide Lennon with words and simple sayings to repeat for a time, mantras to work into his day, being, consciousness. “No one cared” is the central phrase of this short tape, both theme, mantra, confession, expressed fear, phrase of the utmost vulnerability. The singer is owning that notion by expressing the fear. They care. They’re not complaining; this is an act of spiritual and emotional vetting. Of airing out the ship’s hold.

And then Paul joins him on a second demo tape!

People made a huge deal about where the Beatles came from. They still do. It’s a massive part of their story and legacy. Liverpool. Four lads from Liverpool. If you have heard of the Beatles, chances are, you know they are from Liverpool. You can’t do that with any other band. Not to the same degree. Where are the Rolling Stones from? Even if you know the answer, it’s not the same. There’s not that twining. The inseparability.

I feel like the Beatles were haunted by location. Lennon always was. Haunted by who wasn’t there, who should have been. Haunted by doubt. Haunted by a lack of reinforcement about what were this particular individual’s best qualities.

I feel like the Beatles were haunted by location. Lennon always was. Haunted by who wasn’t there, who should have been. Haunted by doubt. Haunted by a lack of reinforcement about what were this particular individual’s best qualities.

A tenet of “Strawberry Fields Forever” is experiencing loneliness because one isn’t what most others are. Not because one is anything bad or lacks for amazing qualities, but instead because of them.

People often don’t know what to say to someone who is different, before everyone else is saying it. Later in life, a lot of people called Lennon a genius. But no one said that to the pre-fame Lennon. He was isolated, rather than celebrated, with the terror that not only would no one know him, no one would accept him. Or not for the right reasons: namely, who he was, with what that was out there in the open.

The studio version of “Yellow Submarine” isn’t swashbuckling, and we’re not lighting out on a Melville-like adventure. But we are having a fun and mysterious ride, with plenty of conviviality and appropriate maritime splendor, but cool, quirky splendor.

The composition tape version is a journey of the insides. The submersible—which presumably hasn’t been formally conceived of yet by Lennon or McCartney—is making a tour, out of time, around these internal seas of this narrator/singer. It moves through storms, the rainwater sinking through the ocean layers, pelting the top of the craft as she continues on.

Or maybe it is the submarine in dry dock, for all to see, which isn’t how submarines work. It’s against their nature. They’re meant to be submerged, not out in plain view. And maybe that is our inclination as well, though it doesn’t serve us well.

Listen to Take 4, with Ringo Starr singing lead, but before the sound effects were added

This is the naked submarine. It’s such a Lennon-esque vessel. The fragment-song is also a ghost story of dreams abandoned, fears that remain, a time and place that has been left, because going away was of the essence. Of the saving essence.

Listen to the highlighted sound effects, as they recording process moved along

But being saved does not make us whole. Being saved often means remaining intact enough. Once we are haunted, we never return—not completely—to our previous, pre-haunted state. The sea ghosts—and the ghosts of the port town—are alive and well in this demo, if it’s even a demo. I don’t know what it is in the taxonomical sense. But it also doesn’t matter. We’re beyond the trappings of labels, and the factoid.

Related: Ron Campbell, animator of the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine film, died in 2021

That we go from this, to what we now know as the finished song, is as wide-ranging a journey as any the Beatles ever undertook with a single piece of music. If Lennon played this tape for McCartney and producer George Martin—and we have no idea if he did—I bet their reaction would have been similar to when he sat on a high stool before them and worked his way through “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

Listen to the 2022 stereo remix of the song we’ve loved for decades

There was courage in making this music, and courage in making vastly different music from this music. People will talk about any port in a storm, just as they talk about the Beatles and Liverpool. This was the Beatles looking for the right port, insisting on no other, and that notion is equally applicable to what Lennon was doing on his own, when he sang his own sort of “For No One”—“And no one cared, no one cared”—with this proto-“Yellow Submarine,” and when the Beatles fashioned a work I knew was made for my back pocket, so that I could always have it with me.

And now I have something else in the other one to go with it, which is perhaps why pockets come in twos. Music to take with you, and music to take you. That’s the kind that is the easiest to love, and the easiest to care the most about.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationVery well written!