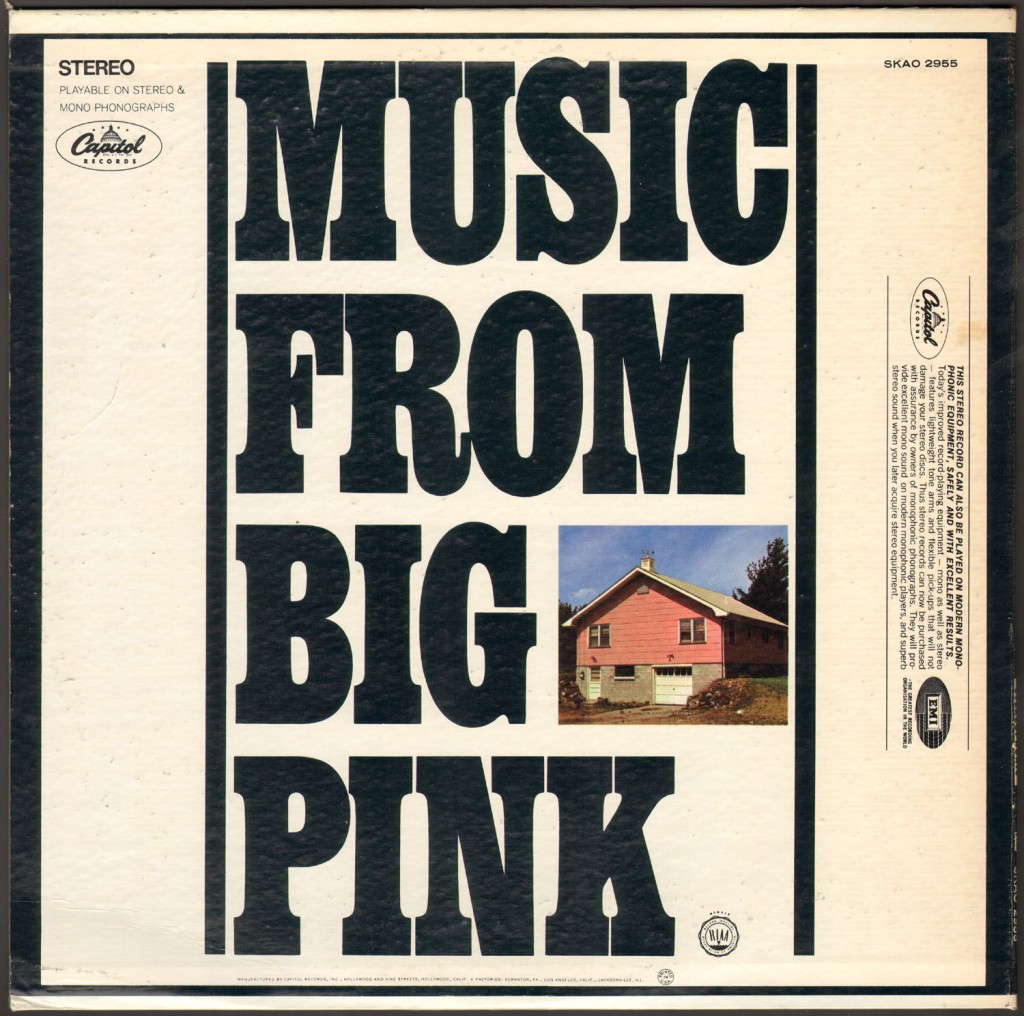

The Band and Their Pioneering ‘Music From Big Pink’: Review

by Sam Sutherland Few game-changing albums open as quietly as Music From Big Pink, the 1968 debut for The Band. A languid but brief motif of single Telecaster notes wheezing through a Leslie speaker staggers in on top of weary, muffled drum beats, anchored by gospel piano chords. And then Richard Manuel begins singing, his soulful, broken-hearted voice breaking as it climbs:

Few game-changing albums open as quietly as Music From Big Pink, the 1968 debut for The Band. A languid but brief motif of single Telecaster notes wheezing through a Leslie speaker staggers in on top of weary, muffled drum beats, anchored by gospel piano chords. And then Richard Manuel begins singing, his soulful, broken-hearted voice breaking as it climbs:

“We carried you in our arms on Independence Day

And now you’d throw us all aside, and put us all away

Oh what dear daughter ’neath the sun, would treat a father so

To wait upon him, hand and foot, and always tell him ‘no’?”

The antithesis of a conventional, radio-friendly earworm, “Tears of Rage,” written by Manuel and his erstwhile boss, Bob Dylan, was a lagging dirge of inventoried betrayal and lost innocence against brooding organ. A mournful duet of soprano and baritone saxophones punctuated later verses, further distancing the record and its authors from guitar heroics and dancefloor energy.

Released on July 1, 1968, Big Pink offered quiet songs of experience bathed in a rustic glow, with no hints of the futurism and none of the kilowatt drama then prevalent elsewhere in rock. Recruited as the Hawks by Arkansas rockabilly veteran Ronnie Hawkins, the quintet had notched years as road warriors playing Canadian and U.S. clubs and casinos, further seasoned by combat duty on Bob Dylan’s tumultuous 1966 tour, adding mileage that imparted a maturity at odds with rock’s youthful entitlement. Still in their 20s (save for keyboard polymath Garth Hudson), they looked and sounded decades older; the black and white portrait on the album jacket could have been taken by Matthew Brady.

The Band, Music From Big Pink album photograph, Bearsville, Woodstock NY, 1968. L-R: Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, Robbie Robertson (Photo © Elliott Landy; used with permission)

Dylan loomed above the project, beginning with the whimsical surrealism of his cover painting. His collaboration with the Band’s members on the “Basement Tapes” was as yet only hinted at; most fans were yet to understand how that prolific woodshedding project was rebuilding an “old, weird America” from the raw materials of folk art. The Dylan tracks on Big Pink already carried the Band’s DNA from their gestation in the Saugerties, N.Y., house that conferred the album’s title, an acknowledgement that the very essence of the group’s ensemble style had been pared away and rebuilt from its foundations as a result of the collaboration, signaled by the first single.

On “The Weight,” Levon Helm, the group’s lone American, recounted a journey that seemed part pilgrimage, part parable, part shaggy dog story written by guitarist Robbie Robertson. Quasi-biblical allusions and picaresque characters raised more questions than answers. The music itself was at once plainspoken and deliberate, proceeding with an unhurried gait. Hearing three distinctive voices build the vocal harmonies on the choruses evoked a brotherhood that itself emerged as part of the album’s mystique and the Band’s identity.

There were no grandstanding solos in this music, with Robertson reining in formidable chops to pare his playing to spare decoration rather than guitar heroics. Once eager to face off in cutting sessions with peers such as Roy Buchanan, on Big Pink Robertson rejected contemporary pedal effects to distill his playing into economical fills closer to R&B heroes like Curtis Mayfield and Pops Staples.

Hudson’s pitch-bending Lowery organ and Manuel’s piano provided the ensemble’s foundation throughout, with Hudson and producer John Simon adding horns that nodded as much to early jazz as ’60s soul music for their brio. Vocally, the arrangements highlighted Manuel’s lyrical growl, steeped in Ray Charles’ protean influence, Rick Danko’s buoyant yelp and Helm’s Arkansas drawl; gospel’s call-and-response interplay was their default setting (with the Staple Singers again a conscious reference point), capped by wide intervals rather than the close harmonies of most bands. Robertson stepped up as a lead singer on just one of his compositions, “To Kingdom Come.”

Related: The Band’s 2nd album, a rustic masterpiece

Overall, their ensemble interaction verged on telepathy, recorded with a documentary clarity during initial sessions at New York’s A&R Studios that were captured live to four-track tape and showcased an easy agility in swapping voices and instruments. The songs likewise reflected a democratic interdependence that would later give way to Robertson’s emergence as principal songwriter and a corresponding ambition.

Robertson crafted that evocative first single, but Big Pink gave nearly equal space to Manuel, proving him to be as evocative a songwriter as he was a singer. “We Can Talk” offers a hearty mid-tempo rocker framed between Manuel’s rollicking piano and Hudson’s organ arpeggios as the three singers traded overlapping lead vocal lines through lyrics that nodded to the era’s political turmoil with a playful allusion to the group’s Canadian majority.

As impressive as that song remains, however, it’s as a balladeer that Manuel would be most compelling. “Lonesome Suzie” is a tender, sympathetic portrait of romantic rejection and abject loneliness that implies Manuel’s own inner pain, while “In a Station” is a hushed reverie that sonically and lyrically evokes a borderland between waking and dreaming.

Bassist Rick Danko also steps up with his own Dylan co-write on “This Wheel’s on Fire,” decorated with twinkling keyboard accents on a cheap Roxochord keyboard Hudson had hot-rodded with a telegraph key, while the set’s third Dylan contribution, “I Shall Be Released,” further extends the scriptural atmosphere evident in a number of “Basement Tapes” compositions and destined to reappear across the bard’s catalog.

Related: Photographer Elliot Landy on The Band

If Big Pink consciously rode the throttle to focus on the quintet’s collective sound, they did flex their power on “Chest Fever,” a semi-nonsensical paean to a wild lover that builds upon Hudson’s formidable intro, itself a virtuosic goof on Bach’s Toccata in D minor that would metastasize over the years into a concert highlight as “The Genetic Method.” Here, it leads into a hard-charging, semi-delirious rave-up that breaks for a giddy middle-eight as all five members and producer Simon bleat away on various horns like a stoned Salvation Army band.

With its anachronistic glance toward a mythical past and idiosyncratic group sound, Music From Big Pink set its hooks into fans gradually but deeply. Musicians, on the other hand, were stunned by the Band’s musicianship, songcraft and democratic spirit, inspiring artists from both sides of the pond to search such fellowship, with Eric Clapton and George Harrison just two of the more prominent acolytes. The rich roots music sensibility underpinning the album with folk, gospel, blues and country elements meanwhile planted vital seeds that buttressed the imminent rise of country-rock, as well as the subsequent emergence of Americana at the turn of the millennium.

Related: An audience member revisits The Last Waltz

The Band would attain greater success with their self-titled sophomore set and on tours that clinched their exalted standing as live performers, but the unraveling of the trust and affection that had forged a brotherhood would finally bring the quintet’s run to a close in 1978 with the ambitious farewell concert and live theatrical release, the Last Waltz. By then, the Band’s influence was signified by the all-star lineup of guest artists (Clapton among them) that would share the stage and screen, but one of the film’s most affecting moments remains a post-concert performance filmed on a soundstage. Watching the Band perform “The Weight” in league with the Staple Singers, a point source for the song and influence on Robertson and his bandmates, the sense of tradition enduring and renewed is inescapable.

[In 2018, Music from Big Pink was released in newly remixed and expanded 50th Anniversary Edition packages. The album, and other pioneering recordings from The Band, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThis is a lovely and insightful diagnostic commentary of one of the era’s seminal recordings. My only question is: What Robbie Robertson had you been listening to? A terrific songwriter he is, though many rightfully question how much of the Band’s recorded output was actually from the seeds of his creativity and imagination alone. But, unless I’m missing something, somewhere, as a guitar player myself, of over fifty years, Robertson was never that much of a guitar player, and, aside from his songwriting, was the weakest musical link in The Band. I firmly believe that your point about “Robertson reining in formidable chops to pare his playing to spare decoration rather than guitar heroics” is because that’s all he was, and is, really capable of. Whenever he’s actually tried to pull off a guitar solo, it’s been at an amateur level. the only other famous guitar player I know who plays with such struggling and nondirected efforts is perhaps Keith Richards, who’s minimalist approach, like Robertson’s compliments his band’s music. I guess it’s Robertson’s dashing presence and as the primary spokesman for such an innovative band that’s somehow transposed into somehow giving him a mystifying kudos of being a great guitar player. He doesn’t play much in the way of these “cutting session” type guitar parts (against Roy Buchannan? You’ve got to be kidding me) on his own solo records, and if you see him play on the stage at Clapton’s Crossroads festival, it’s pretty pathetic. Fortunately, The Band’s recordings were never about his guitar being a featured element, and his limited ability did provide a sound and style that clunked along harmoniously with the music. A more traditionally better guitar player would have changed the character of the music significantly, and probably weighted it down with a more cliched approach to rock and blues.

I completely agree with you about Robertson’s guitar chops. He’s a wonderful songwriter and presence, and he really helped steer The Band to prominence, but he’s definitely no guitar hero like Clapton or Buchanan. Not even close. He plays for the song, which is commendable (and more people should do it), but he just doesn’t have world-class guitar chops. And that’s okay. He doesn’t need them, and neither did The Band. The songs he wrote hold up just fine without guitar histrionics.

From what I’ve read in many other places The Weight and many other of The Band’s songs were more a collaboration of the group than just Robbie Robertson.

Robbie Robertson was no Roy Buchanan as a guitar player, but then Roy was no Robbie as a song writer. The Band was always more about the amazing synchronicity as 5 musicians then anything else. The elephant in the living room is how drugs and alcohol washed away most of that talent in the end. The rock and roll lifestyle ain’t all its cut out to be. If I want guitar virtuosity I look to Frank Zappa. There are tons of great guitar players but great song writers? Not so many. As Dylan said, “Sad-eyed Lady of the Lowlands, try writing something like that sometime”. Indeed!