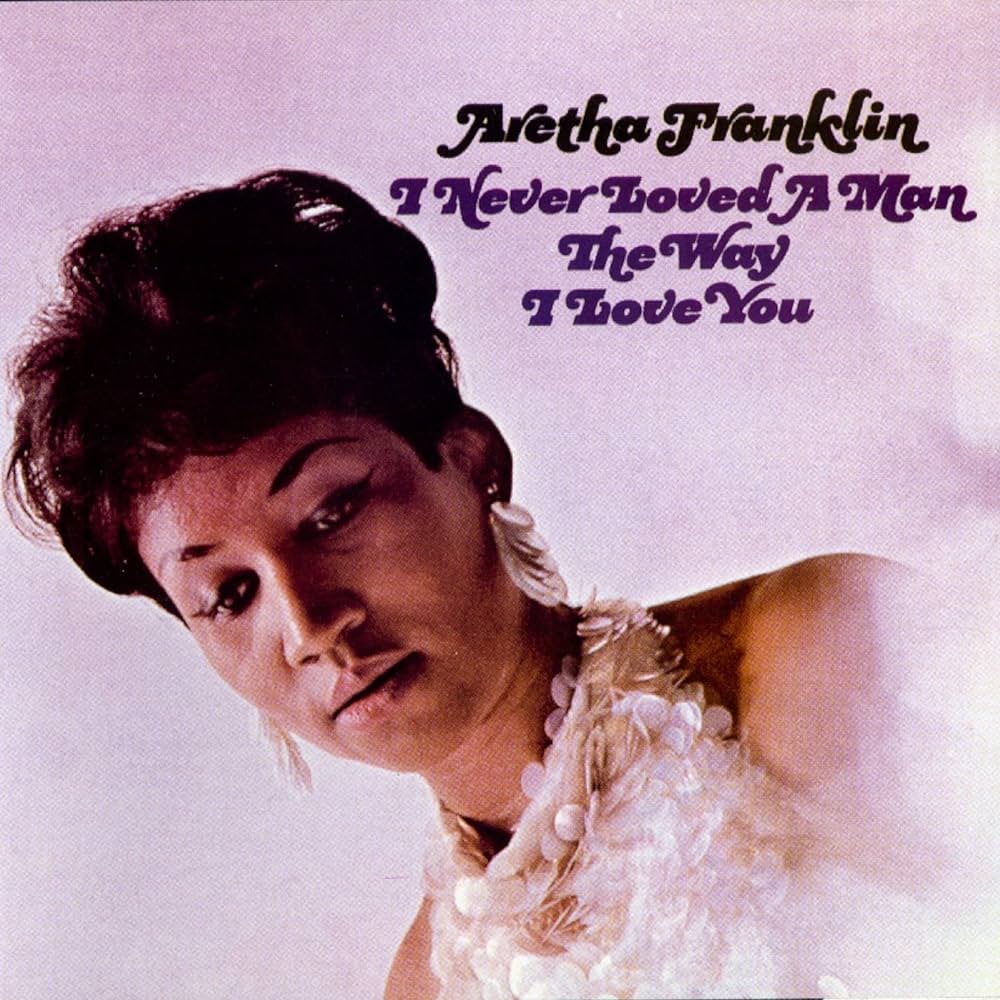

Aretha Franklin’s ‘I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You’ LP: R-E-S-P-E-C-T

by Mark Leviton In late 1966, Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler finally signed Aretha Franklin to a recording contract, after watching her career at Columbia Records go nowhere for several years. Her nine albums for Columbia mixed Broadway show tunes, gospel, easy listening, pop and jazz, without ever finding the proper setting for her extraordinary talent. Franklin‘s biggest hit on Columbia was a borderline embarrassing version of “Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody,” which peaked at #37 in Billboard.

In late 1966, Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler finally signed Aretha Franklin to a recording contract, after watching her career at Columbia Records go nowhere for several years. Her nine albums for Columbia mixed Broadway show tunes, gospel, easy listening, pop and jazz, without ever finding the proper setting for her extraordinary talent. Franklin‘s biggest hit on Columbia was a borderline embarrassing version of “Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody,” which peaked at #37 in Billboard.

“They handed her the songs and arrangers and she had no choice,” Wexler told the journalist Tom Cox. “When she came to me, I utterly involved her in the selection of material and made her an organic part of the recording process. We went south and recorded inductively, and she always had the last word.”

As Wexler wrote in his autobiography Rhythm and the Blues, “She was not an innocent. She was a twenty-five-year-old woman with the sound, feelings and experience of someone much older. She fit into the matrix of music I had always worked with—songs expressing adult emotions. Aretha didn’t come to us to be made over or refashioned; she was searching for herself, not for gimmicks, and in that regard I might have helped. I urged Aretha to be Aretha.” That also meant he wanted Franklin, a startlingly soulful pianist, to feature that instrument alongside her impassioned vocals.

After being rebuffed by Stax Records’ Jim Stewart when he wanted to send Franklin to Memphis to record for that venerable label, with which Atlantic had a distribution deal, Wexler took her to Rick Hall’s FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. What happened there has been the subject of rancorous disputes ever since the musicians gathered on Jan. 10, 1967. Wexler always claimed he wanted Hall to hire a horn section made up of Black musicians, because he was anxious about how Franklin and her manager-husband Ted White might react to the “bunch of white Southern crackers” that worked with Hall. “It bothered me that she walked into the studio and didn’t see another Black face,” Wexler told Cox. “But Aretha has never had a spark of racial prejudice in her. She didn’t say a word.”

With Aretha on acoustic piano and Dewey “Spooner” Oldham on electric piano, and all the other musicians recording live, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” was tracked. Written by Detroit’s Ronnie Shannon, the song and Franklin’s intense vocal performance electrified the musicians. Drummer Roger Hawkins later said, “I’ve never experienced so much feeling coming out of one human being.” But alcohol was consumed, and one of the musicians reportedly went too far with the general teasing and goofing off. Did he really hit on Aretha? White thought so.

After two hours completing that song and getting halfway into “Do Right Woman–Do Right Man,” the session ended with tension in the air, especially between Hall and White. At the Downtowner Hotel in the wee hours, Hall tried to smooth things over and instead, he later admitted, got into “a full-blown fistfight,” with White, while Franklin tried to break them up. Wexler, whose room was nearby, visited White at 6 a.m., and told biographer David Ritz that White was apoplectic, screaming about how he and his wife had been mistreated. By noon, White had taken his wife back to New York City.

Undeterred, Wexler flew some of the Muscle Shoals musicians, informally known as the Swampers, to New York, added a few of his local regulars, including saxophonist Curtis Ousley (King Curtis), and completed Franklin’s debut LP for Atlantic at their own 1841 Broadway studios, with the brilliant Tom Dowd engineering. (One account says Wexler lied to Hall about the Swampers coming north to work only on King Curtis’ Plays the Great Memphis Hits sessions.)

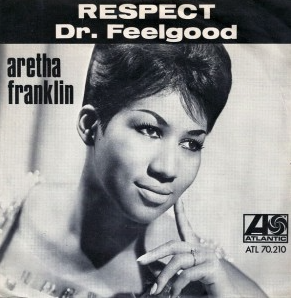

Released on March 10, 1967, a mere two weeks after the final “sweetening” recording sessions, I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You was an immediate smash, not only because of the title track, which as a single made the Billboard top 10, but for the LP’s first cut, Franklin’s landmark version of Otis Redding’s “Respect,” which made it to #1 as a 45 in June.

“To tell the truth, I never expected ‘I Never Loved a Man’ to be a hit,” Franklin told Norman Jopling in a rare 1968 interview. “I was surprised. I could see more potential in ‘Respect.’ In fact, I can say I knew that would be a hit song,” Redding had recorded it two years before, and his version fit into a long-standing social template, in which a male breadwinner demands credit—and access to good lovin’—for his efforts.

Related: Watch Aretha Franklin duet with Tom Jones

Repurposed for a female singer, the concept of “respect” expands beyond home life and into all of American society. In Franklin’s performance, she demands respect as both a woman and a Black woman. She was always a bit coy when discussing the connection to the Civil Rights and feminist movements, telling the Detroit Free Press, “I don’t think it’s bold at all. I think it’s quite natural that we all want respect—and should get it.”

Franklin, Wexler and Atlantic staff arranger Arif Mardin vastly improved on Redding’s rough-hewn arrangement. The background singers—Aretha’s sisters Carolyn and Erma with Cissy Houston—serve as a Greek chorus as the drama of the track spreads out during a fully packed 2:29 timing. The “sock it to me” grind and spelling out “r-e-s-p-e-c-t” are genius moves. Jimmy Johnson’s guitar, Oldham’s Hammond organ, King Curtis’ tenor sax, Hawkins’ insistent drumming and Franklin’s piano all mesh into one of the greatest of all recordings in any genre.

Henry Glover’s “Drown In My Own Tears” which had been cut by Ray Charles for Atlantic in 1956, begins with a powerful starkness, Aretha’s voice and piano laying down gospel licks with bassist Tommy Cogbill before Hawkins—or perhaps alternate Swamper Gene Chrisman—enters. The robust arrangement for four-piece horn section (trumpeter Melvin Lastie, Willie Bridges on baritone sax and Charles Chalmers and King Curtis on tenors) buoys the track even more. Franklin’s vocal calisthenics are astounding; she’s always on the move, turning melody lines around, shouting, exclaiming. She takes liberties with the phrasing just as Charles did. Listen to how she handles “I’ve been crying just like a child/These tears of mine, these tears are runnin’ wild” about a minute in.

“I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” is next. From the moment Franklin insists, “You’re no good, heartbreaker/You’re a liar, and you’re a cheat,” over Oldham’s electric piano, the listener can’t help but be riveted. Franklin’s muscular piano becomes more central as the track unfolds, and her ability to explode pitch-perfect vocal notes into her upper range is startling. How many words have already been written trying to discern how Jerry Wexler and Aretha Franklin found the alchemy that others failed to discover? The recording is a Mount Rushmore of Rhythm and Blues.

The languid “Soul Serenade,” written by Luther Dixon and King Curtis, had often been performed as an instrumental ever since Curtis’ 1964 hit version for Capitol Records; this version with lyrics, while beautifully sung, is not a highlight of the LP.

“Don’t Let Me Lose This Dream,” written by Franklin and her husband, is a bossa-nova that sounds not unlike a Bacharach-David song for Dionne Warwick. The lyrics are plain, but Franklin does her best to sell them: “If I lose this dream/It’s goodbye love and happiness/You’re the one I need/I don’t want a love that’s second best.” Musically, the bridge section at 1:50 is one of the strongest parts.

The lyrics are especially heartbreaking now that we know Ted White wouldn’t last much longer as Franklin’s spouse, after years of abuse and co-dependency that Aretha excused by referring to him as “a take-charge kind of guy,” As she told NME’s Alan White in 1968, “I might be just 26, but I’m an old woman in disguise—26 going on 65. Trying to grow up is hurting, you know. You make mistakes. You try to learn from them, and when you don’t, it hurts even more. I know what it’s like. I’ve been hurt—I’ve been hurt bad.”

“Baby, Baby, Baby” was written by Carolyn and Aretha Franklin. Oldham’s organ is in support of Franklin’s stately piano once again. The call-and-response with the harmonizing female trio has some hokey moments, like when “If loving you was so wrong/I’m guilty of this crime” is echoed by “I’m guilty, I’m guilty, I’m guilty,” but the juxtapositions most often work well, as when Aretha sings, “I’m lonely and I’m loveless without you to hold my hand” and the response is “reach out for me, boy.”

There’s something very real and soulful about how Aretha calls her lover “baby,” an endearment she returned to many more times, including for another smash written by Ronnie Shannon, “Baby I Love You,” the only single pulled from her follow-up and second LP of 1967, Aretha Arrives.

“Dr. Feelgood (Love Is a Serious Business)” leads off side two of the original LP, and is wonderfully loose and unabashedly sexy. This is one of the best examples of how White and Franklin could co-write with real heat and from their attraction to each other. Listen to the spectacular way she stretches out a single “oh” at 1:47 into a scream of passion, leading into “when me and that man get to lovin’/I tell you girls/I dig you but I just don’t have time to sit and chit and sit and chit-chat and smile.”

The story goes that the “real” Dr. Feelgood was Dr. Max Jacobsen, who was given that name by Secret Service agents during the Kennedy administration, since he was well-known as a purveyor of amphetamines to celebrities, including Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley and the President himself. For this song, substitute sex for pills and you know what makes the singer “feel real good.”

There are two Sam Cooke tunes on side two, “Good Times” and “A Change Is Gonna Come.” As a party anthem the first can’t be beat, and Franklin and company make short, potent work of it. A hit for Cooke in 1964, it’s attracted dozens of cover versions and had wide appeal; Dan Seals had a #1 country single with “Good Times” in 1990, the same year the Grateful Dead used it as a rousing first-set opener. “A Change Is Gonna Come” is now of course a Civil Rights anthem, based on Cooke’s experience of racism while on tour in the South. His stirring version was released as a single B-side in early 1964. The longest cut on the album, Aretha’s take is placed at the very end, after all the playfulness and love songs, and is a deadly serious, focused, emotional masterpiece.

Before that, we get two more performances, the regally impressive “Do Right Woman–Do Right Man,” penned by the Muscle Shoals duo Dan Penn and Chips Moman, and “Save Me,” a light confection that never strays from the same three chords that anchor Van Morrison’s “Gloria.” It’s one of the only songs ever written by Carolyn, Aretha and King Curtis, and is basically a short jam with a rock/boogaloo beat.

One account says Franklin plays both piano and overdubbed organ on “Do Right Woman,” but as this is a FAME/Atlantic Studios fixer-upper, memories differ. “Take me to heart and I’ll always love you/And nobody can make me do wrong/Take me for granted, leaving love unsure/Makes willpower weak and temptation strong” is one of the most tragic, and poetic, statements of a lover’s dilemma in popular music. The behind-the-beat backing vocals on the chorus are expertly designed to keep a somber, mid-tempo number moving forward.

I Never Loved A Man That Way I Love You sold a million copies in 1967, and another couple million since. Most of the initial negative reviews from music critics were taken back later. Upon release, Rolling Stone’s Jon Landau (future manager of Bruce Springsteen) faulted the playing and the production; by 2002 the same publication had it at #1 on their list of “Women In Rock: 50 Essential Albums.” It’s generally considered ‘timeless.”

Aretha Franklin, The Queen of Soul, has never gone out of fashion; when she died at the age of 76 on Aug. 16, 2018, in her beloved Detroit, there was worldwide mourning, and her recordings were played everywhere. She stills gets the respect she deserves. Her extensive recorded legacy is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Aretha sing “I Never Loved a Man” at the 2007 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI don’t think Aretha’s Columbia output was bad, just different than the soul explosion with Atlantic. Kind of like faulting Isaac Hayes for his early 70s exploration of songs such as “Never Can Say Goodbye” while he was pimping that bad mother SHAFT!

When you want to hear something different from Aretha, go back to the Columbia recordings. Granted, I would rather hear an Atlantic version of “God Bless the Child” than the Columbia production.