With three albums released in a two-year period, Bob Dylan was outselling Columbia Records label mates Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, according to his producer Tom Wilson, who had come from a jazz background but was now responsible for several of Columbia’s folk artists. “This kid,” he told The New Yorker’s Nat Hentoff, “is speaking to a whole new generation.” Just before Dylan entered Columbia’s Seventh Avenue recording studios to cut his fourth LP, in a single six-hour session, the 45-year-old folk-singing elder Pete Seeger gave cautionary support when he said the 23-year-old Dylan “may well become the country’s most creative troubadour—if he doesn’t explode.”

With three albums released in a two-year period, Bob Dylan was outselling Columbia Records label mates Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, according to his producer Tom Wilson, who had come from a jazz background but was now responsible for several of Columbia’s folk artists. “This kid,” he told The New Yorker’s Nat Hentoff, “is speaking to a whole new generation.” Just before Dylan entered Columbia’s Seventh Avenue recording studios to cut his fourth LP, in a single six-hour session, the 45-year-old folk-singing elder Pete Seeger gave cautionary support when he said the 23-year-old Dylan “may well become the country’s most creative troubadour—if he doesn’t explode.”

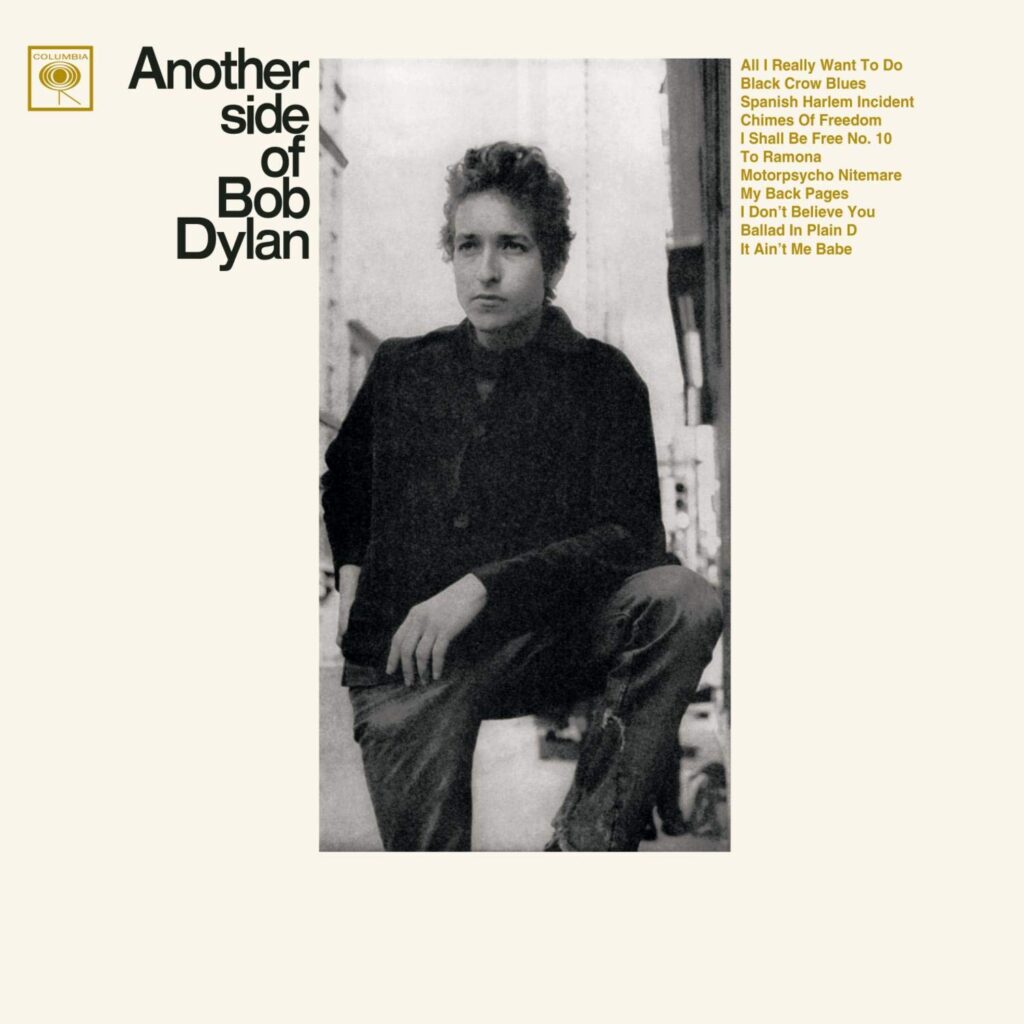

The album eventually titled Another Side of Bob Dylan was recorded on June 9, 1964, starting around 7:30 p.m. Containing 11 of the 14 tunes cut that night, it was released commercially a mere two months later in order to be ready for Columbia’s autumn sales convention. The material represented a turn away from the social commentary of songs like “Masters of War,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” Although he’d always written love songs, light satires and blues as well, Dylan’s recent travels with his friends in America and Europe, and the disintegrating relationship with his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, focused him strongly on the people and events nearby.

At the recording session, Dylan described to Hentoff what he had in his notebooks for that night: “There aren’t any finger-pointing songs in here. Those records I’ve already made, I’ll stand behind them, but some of that was jumping into the scene to be heard and a lot of it was because I didn’t see anybody else doing that kind of thing. Now a lot of people are doing finger-pointing songs. You know—pointing to all the things that are wrong. Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know—be a spokesman.”

Related: What really happened when Dylan plugged in at Newport?

As he normally did, Dylan would play guitar, harmonica and piano as sole accompaniment to his live singing. Many friends, some with their kids in tow, hung out in the studio while he recorded and listened to playbacks. The red wine and banter flowed, and some kibitzers annoyed the producer: to a hanger-on (possibly Bob Neuwirth) who insisted the lights be dimmed, Wilson replied, “Atmosphere is not what we need. Legibility is what we need.”

Bob Dylan sits in with the Byrds in 1965, a year after the release of Another Side… (Photo from the book The Byrds 1964-1967; used with permission)

On top of those annoyances, Wilson and his Columbia staff engineers Roy Halee and Fred Catero didn’t always agree on how to get the best performances out of Dylan. In Hentoff’s remarkably detailed New Yorker piece “What Bob Dylan Wanted at Twenty-Three,” he reports that when one of the engineers wanted Dylan to run through a number again, Wilson snapped, “Forget it. You don’t think in terms of orthodox recording techniques when you’re dealing with Dylan. You have to learn to be as free on this side of the glass as he is out there.”

Wilson also told Hentoff, “My main difficulty has been pounding mike technique into him. He used to get excited and move around a lot and then lean in too far, so that the mike popped. Aside from that, my basic problem with him has been to create the kind of setting in which he’s relaxed.”

The LP begins with “All I Really Want to Do,” a wryly comic song with a melody that jumps from high to low range as if there are two Dylans passing ideas back and forth. The verses are a list of what the speaker doesn’t require in a relationship, while the two-line chorus employs a Jimmie Rodgers-style yodel to posit a possibly disingenuous wish to “be friends with you.” Dylan actually laughs several times, as he makes up words (“I ain’t looking to fight with you/Frighten you or uptightin’ you”) and invents new grammar (“I don’t want to fake you out/take or shake or forsake you out”). Even the simple harmonica wheezes sound jauntily humorous. And somehow there’s also a serious message about how lovers treat each other, with Dylan confirming he has no interest in “defining” or “confining” his intended.

“Black Crow Blues” features tack piano for a standard 12-bar blues form with an occasionally wobbly rhythm. Dylan’s voice is strong, but the track is fairly inconsequential, with too many damp squibs in the lyrics: “Sometimes I’m thinking I’m too high to fall/Other times I’m thinking I’m so low I don’t know if I can come up at all.”

“Spanish Harlem Incident” packs a lot into 2:24. It begins with a personified neighborhood uptown: “Gypsy gal, the hands of Harlem/Cannot hold you to its heat/Your temperature’s too hot for taming/Your flaming feet are burning up the street.” The beseeching words continue with a swooping melody, mostly at the top of Dylan’s range, directed straight to that objectified, tantalizing female with the “pearly eyes.” Unusual juxtapositions add mystery: “on the cliffs of your wildcat charms I’m riding.” The influence of Arthur Rimbaud, one of Dylan’s favorite poets, is clear.

The powerful “Chimes of Freedom” was rebuilt from a poem about President Kennedy’s assassination, where cathedral bells are “striking for the gentle/striking for the kind/striking for the crippled ones/And striking for the blind.” Now, with a stirring musical setting, they’re “striking for the gentle, striking for the kind/striking for the guardians and protectors of the mind.” Like “Mr. Tambourine Man,” which was recorded for Another Side but left off the final track list, “Chimes of Freedom” was at least partly written in the back seat of a station wagon during a three-week road trip in February ’64, when Dylan would sometimes perch a typewriter on his knees or cover notebooks with verse after verse of some new invention while a friend drove.

Dylan plays with the effect of synesthesia, where the senses get scrambled: chimes can flash, sounds can have shadows and “the sky cracked its poems in naked wonder.” There are still political messages, but they are abstract: “Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed/For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones and worse/And for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe.” “Chimes of Freedom,” with its seven minutes of cascading verses, draws a line in Dylan’s work, separating what came before from what will emerge on his next two releases, Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited.

“I Shall Be Free No. 10” is a talking blues in the style of Woody Guthrie, very much like “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” “Talkin’ Bear Mountain Massacre Blues” and other trifles that Dylan was in the process of transcending. Making room for this silly, even juvenile performance, with its now dated references to Barry Goldwater and Cassius Clay, is a blot on an LP trying to look forward. “I’m gonna grow my hair down to my feet so strange/So I look like a walking mountain range,” coming after the depths of “Chimes of Freedom,” is just odd. Maybe he was trying to please the entourage that was treating the session like a cocktail party, but Wilson obviously went along with the joke.

“To Ramona” is the shortest song on the album, a beautifully loping waltz that might have roots in a Mexican folk song, but which Dylan wrote while visiting Greece in the company of the singer/model Nico. Like many Dylan songs, the protagonist is giving advice to someone else, warning them about blood-suckers and phonies, eventually revealing his own vulnerabilities as a punch-line: “I’d forever talk to you, but soon my words/Would turn into a meaningless ring/For deep in my heart/I know there is no help I can bring/Everything passes, everything changes/Just do what you think you should do/And someday maybe, who knows, baby/I’ll come and be crying to you.” In some places, you can hear Dylan struggle with syntax and rhyming as he crams in words awkwardly: “From fixtures and forces and friends/Your sorrow does stem.”

Leading off the second LP side with the trivial “Motorpsycho Nightmare” is another strange choice. It’s a corny traveling salesman yarn welded onto Hitchcock’s Psycho. Rhyming “Rita” with “La Dolce Vita” and “jerkin’” with “Tony Perkins”? No thank you. Dylan basically did the song over again the following year, with different lyrics, as “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” and it’s much more clever and funny there.

Naturally, the profound “My Back Pages” follows, keeping up the LP’s split personality. As a renunciation of the past it has a bittersweet quality, six verses of dense words and images matched to a highly controlled yet emotional melody. It’s one of Dylan’s best vocals. Attacking the “lies that life is black and white,” he takes aim in the starting line of each section: “Half-wracked prejudice leaped forth, ‘rip down all hate,’” I screamed,” “A self-ordained professor’s tongue too serious to fool,” “In a soldier’s stance, I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach.” By the end, there’s some kind of wisdom. It might be tentative, but a transformation has occurred: “Good and bad, I define these terms quite clear, no doubt, somehow/Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.

At over eight minutes in length, “Ballad in Plain D” maintains its chillingly downbeat feel. According to Dylan scholar Clinton Heylin, the melody and some of the lyrics are based on the Scottish song “I Once Loved a Lass.” Dylan has admitted it was his extensive kiss-off to Suze Rotolo and her “parasite sister” Carla, and several times has said he regrets writing it. It’s one of the most painful, heartbreaking performances Dylan ever laid down; his break-up songs on Blood on the Tracks 10 years later at times reflect the continuing sorrows of “Ballad in Plain D.”

The album concludes with “It Ain’t Me Babe,” which fuses a “Scarborough Fair” arrangement onto an opening line and general approach borrowed from John Jacob Niles’ “Go ’Way From My Window.” Again, as in “All I Really Want to Do,” Dylan plays with the positive and negatives poles of love, claiming a potential lover – who’s apparently hanging around outside his apartment waiting for an audience—will only be disappointed with his lack of character and general unworthiness. And if that’s not enough, the singer provides the gut-punch that he’s entertaining another lady anyhow: “Go melt back in the night/Everything inside is made of stone/There’s nothing in here moving/And anyway I’m not alone.” It’s a brush-off with the style of Lord Byron.

The album, released on August 8, 1964, was a commercial disappointment, peaking at #43 in Billboard. The folk world tastemaker Irwin Silber of Sing Out magazine penned an open letter complaining to Dylan that “your new songs seem to be all inner-directed now, inner-probing, self-conscious,” and insufficiently political. Pop musicians embraced the LP, which perhaps helped blacken it further with the folkies who thought electric guitars were the devil’s instruments—at least until Dylan himself plugged in.

The Byrds eventually recorded four of the songs on Another Side, after turning out their first hit based on the rejected version of “Mr. Tambourine Man” they managed to obtain as Columbia Records’ hip new band. A re-cut version by Dylan, without Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s duet vocal, appeared on Bringing It All Back Home; the original is available on the No Direction Home compilation. Johnny Cash and the Turtles recorded “It Ain’t Me Babe,” and Cher had a pop hit with “All I Really Want To Do.”

Even the outtakes from the album, like “Mama, You Been On My Mind,” were recorded by the likes of Joan Baez, Judy Collins and Rod Stewart, and other contemporaneous songs, such as the gorgeous “I’ll Keep It With Mine,” were left for others to issue. Even with Another Side of Bob Dylan settling into its position as an orphaned “transitional album,” the future Nobel Laureate was soon busy cutting his own pop hits with rock instrumentation, including “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” “Positively 4th Street” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” Bob Dylan is, of course, still on the Never Ending Tour that began in 1988, and turned 83 years old on May 24, 2024. His recorded legacy, with many expanded editions, is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Dylan perform “It Ain’t Me Babe” live in Portugal in 2018

Bonus video: Listen to Cher’s hit cover of “All I Really Want to Do”

A new collection focusing on covers of classic early tracks by Dylan, has been released by Cherry Red Records. I Shall Be Released: Covers of Bob Dylan 1963-1970 arrived July 25, 2025. The 3-CD set of 63 tracks is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationAnother Side has a youthful, humorous bent to its songs. And I first listened to it as a teenager, enjoying very much its silly humor songs, and not caring too much, yet, about how professional his long lyrics looked or sounded. Perhaps, out of all Dylan’s albums, both Another Side (1964) and Street Legal (1978) seem to be tied to transitional years . . .

Dylan is a magnificent songwriter but a horrible singer and performer. He shows little or no consideration for his audiences (you know, the people who pay money to see him perform?). He mumbles, changes arrangements so you can’t recognize what song he’s playing, and many times has the stage lit so that you can barely see him. I wouldn’t walk across the street to watch him play for free. I much prefer hearing other people sing his songs.